Imagine if you could taste a multitude of chemical personas. What if you could inhabit the mind of a cannibal or a hormonal teenager? Thus murmurs a commercial flavourist in my ear, as I shadow her hunt for a mythical orchid in the Brazilian Amazon. To encounter a work by Anicka Yi is to potentially encounter deep-fried flowers, live snails, cultivated human-borne bacteria, girl scout cookies, ants, oxytocin-injected snails, or recalled powdered milk. A list of ingredients that points to her unique entrance into the art world: a self-directed study of science. Guided by narrative as her starting point, Yi inhabits the experimental fringes of cuisine, biology, and perfumery, from which to challenge a certain conservatism surrounding the nose that, she says, mutes our experiences and interactions. Using unorthodox combinations of esoteric ingredients, materials that are, or were recently, alive, Anicka examines how ‘flavours’ – visual, olfactory, gustatory, auditory – can spur longing, form sense memories, and reconfigure politics of taste. Often, one experiences this through a physical and instinctive experience of disgust, compelled nonetheless by unfamiliarity. By the hybrid, adapted, mutated, and transformed. Working primarily with smell to sensitize herself to the oldest, most animal forms of communication, Yi’s works tap into the ‘basement’, that is to say, our animalistic inner cores: a territory in which to make felt the various social, cultural and economic measures that condition and limit our senses, and the potential for their evolution.

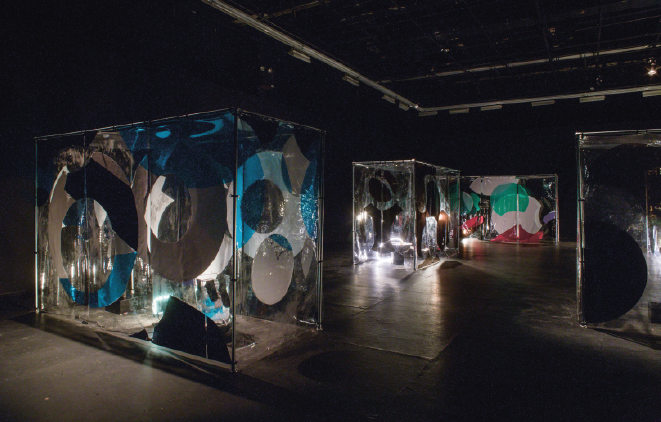

Still from The Flavor Genome, 2016 Courtesy: the artist and 47 Canal, New York

Rosa de Graaf: What’s a distinct memory from your upbringing?

Anicka Yi: You know, it’s interesting because, as a young person, you’re very weak – you’re still forming, developing a

self, even if that self is a myth or a fantasy. But for me, growing up in the Deep South in America during the seventies, and coming from immigrant parents, something I remember experiencing was that there really weren’t a lot of people like us, being Asian.

You have this early, not just visual, racialization, but also environmental and atmospheric racialization. Back in the seventies and even to this day eating very pungent foods, staples in the diets of Koreans or Korean-Americans, such as kimchi, which is very fragrant, was very openly racially charged and maligned as being offensive to white Western bodies. It’s in the air. It’s an actual perceived toxicity, a harmful violation of clean airspace, and also of personal space. This is especially the case in America, when it comes to vigilance over personal space. It was immaterial, so to speak. It’s something that we’re breathing, the air from the noxious clouds hanging over every big metropolis’ China Town. It’s something that seemed far more threatening and mysterious because of that, and certainly misunderstood. As long as I’ve lived here, every summer I’ve heard about how foul Chinatown smells in August, because of the garbage, the food, and what have you. By contrast, in regions of mid-town Manhattan, there’s endless construction and toxic paint fumes, which are not racialized.

I think that was a very early, palpable cognition, without understanding fully where it was coming from, or why it was, and also not realizing that thirty years later, I would be able to articulate it and address it in my work.

Structured as an episodic narrative, The Flavor Genome (2016) stems from Anicka Yi’s field-research in the Amazon.

Combining inspiration and findings drawn from a range of sources, from world orders figured in science fiction, to cultural interpretations of taste, to beliefs of indigenous Amazonians. The narrative unfolds in renegade laboratories within the Brazilian Amazon, and is told through a commercial flavourist, who is on the hunt for a mythical orchid of miraculous properties. The work combines 3D-film footage shot by the artist on location, as well as 3D animation, as part of a larger investigation by the artist into perception, exploring potential forms of adaption, mutation, and hybridization of living organisms. Rosa de Graaf

Rosa: Indeed, this experience of palpability occupies a particular presence in your works, particularly those that engage the non-ocular senses, such as smell.

Anicka: Yes, it ties in to a lot of my main theses around olfaction, per se, in terms of the way in which our perceptions around the senses are conditioned politically. It is not some accident that we attribute smell as feminine, and so forth, with the different senses. Those are some very early strong shaping memories and experiences, and that has always carried me through. Because it’s not as though the world has gotten

more enlightened around these issues; these experiences tend to build on themselves.

Rosa: Where are you currently in your life?

Anicka: That’s a difficult question to answer. I’m in a very hyper-alert space. Hyper-aware. And edging forward constantly.

Rosa: And, work?

Anicka: I could almost say the identical thing. Hyper-aware. Hyper-alert. I’m extending a lot of my main thesis, and trying to articulate the extending paradigm for my work, as well as existence at-large, and thinking about the transformation of the human, and the de-centring of the human.

Rosa: De-centring the human, while at the same time, your work is frequently described as a sensorial engagement as elaborated through an experience of bodily affects. How far does attraction – in an intuitive sense – figure in your cultivation of these corporeal encounters?

Anicka: I think desire is something that is really difficult to understand. I don’t think scientists even really know where desire comes from, other than that it’s part of a larger algorithm. That algorithm is comprised of our genes. Our very crowded genes, and our environment, as part of a larger system. In terms of desire, I think I was definitely part of a tradition of isolating desire, something that could be independent, even politically, of

the biological drives, and the algorithm of biology.

Without diminishing the power of desire, I have a more sober relationship with it. So, to answer your question, to contextualize where my head space is, I think one’s desires are largely driven by early experiences that imprint themselves onto ‘the algorithm’. Like the example I gave you about growing up in the South in the seventies, and just being definitely targeted as somebody who is an outsider, who doesn’t belong.

…we’re actually more in our bodies when we’re feeling actual disgust because, most likely, we are having a physical reaction towards something that is repulsive, that is reviled or something…

Rosa: In contrast to ‘desire’, then, you have often talked about the role of disgust in relation to your work. The social role of disgust in provoking us to inhale more deeply, to be confronted with smells that we, by default, judge to be offensive or that we are repelled by. In a way, you use disgust as a means to recode some of these limitations?

Anicka: Yeah, repulsion, disgust, and a real, extreme form of disgust, are very important, especially when you’re talking about art, which is constantly having to negotiate itself around beauty, around pleasure, and around some kind of divine sort of experience. In this context, it’s important to also reach ‘the basement’, so to speak – this kind of atrophy. We have a tendency to give these latitudinal properties to emotions and certain sensations, whereas disgust is something that’s very base and low. To me, that signifies something that’s very animal and organic. Whereas when you rhapsodize about Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, you’re transcendent. You’re actually leaving your inner body, reaching divinity or something like that. When thinking about it like that, we’re actually more in our bodies when we’re feeling actual disgust because, most likely, we are having a physical reaction towards something that is repulsive, that is reviled or something. We’re squirming and we’re uncomfortable, we feel nauseous, we have a headache. That’s something that’s in our bodies, and I think that we are attuning to our bodies. This is really important.

There’s also another element to it. We are not comprised of just that which is human. We’re a multitude of beings and organisms, so the self is made up of a lot of tissue and organs, but it’s also bacteria and the microbiome. The microbiome actually influences our thinking. It fires off neurotransmitters. When we’re thinking about certain things, it’s actually the bacteria that’s making those decisions or at least facilitating those decisions. It’s a way to think about oneself as not being some ‘singular entity’, some ‘individual’. That’s just not correct, and it’s a kind of myth that we’ve had to perpetuate. Namely, that we are all unique and that we’re all individuals, and that every single person’s thoughts and emotions matter.

For the installation You Can Call Me F, the New York-based The Kitchen gallery has functioned as a forensic site in which the artist aligns society’s growing paranoia around contagion and hygiene (both public and private) with the enduring patriarchal fear of feminism and potency of female networks. The works gathered biological information from 100 women to cultivate the idea of the female figure as a viral pathogen, which undergoes external attempts to be contained and neutralized. Employing the visual language of quarantine tents, which allow limited transparency and access while aiming to protect their fragile ecosystems within, Yi’s humanist approach foregrounds the politics and subjectivities of smell, and its impact on our empathic understanding of each other. Courtesy The Kitchen

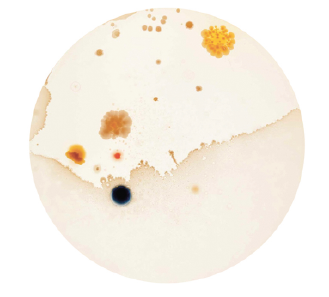

Rosa: The influence of bacteria on one’s thinking and your discussion of the individual makes me think of your work Grabbing at Newer Vegetables,2 included in your exhibition You Can Call Me F at the Kitchen in New York. Constituted by collective bacteria, I wonder: can collective bacteria reconfigure our preoccupation with the individual, opening up to a collective way of thinking?

Anicka: This project started with this kind of bio-fictional sort of narrative, imagining that we could somehow create a super-bacteria. A super-bacteria which people are usually terrified and disgusted by, of course, in so far as this sort of collective of female cells, a female collective, if you like, could become rendered visible as a very crowded body. You know? A body in the collective sense as well as very singular sense. Here, the bacteria functioned as a way to lose some kind of tangible visual form as well as olfactive, because I did translate the smell of the collective female bacteria into a scent as well, which was synthesized.

I’ve always just foregrounded the microbiome in the sense that this is the genesis of life, this is the engine here, and we’re not alone in ourselves – let’s unpack this and let’s talk about it.

Rosa: How important is physical presence for you, in terms of an audience’s experience of your work?

Anicka: I think being present is really vital. It’s an interactive work. You, as a visitor to a bacteria work, contribute your own biota to it. At the same time, by taking in the scent, you’re also taking a part of the work internally inside of you, away, as you leave the space. Those molecules go inside your body, they in a way inoculate you, not in a pathological way or a pathogenic way, but you are biologically impacted by being in that space.

With that being said, and I’m not downplaying how important and vital it is to me with the work that I make and the hopeful intentionality around it, I am thinking about, and have been thinking about, digitizing smells and how it relates to my work currently and where I’m headed and what I’m thinking about in terms of, you know, how do you negotiate the sensorial machine? Will the rise of artificial intelligence signal the end of odours? Especially since as biological organisms, more or less, our sense of smell was an evolutionary survival tool. However, whether we rely on it or not, in the twenty-first century, that’s how it evolved. What does it mean for a machine that doesn’t need to smell for survival, that it could just read the chemical composition of the air? What does that mean in terms of intelligence? I’m thinking about the ecology of the mind and what the new paradigm for that would be? In some ways, it dovetails in the same sort of mental space for me as art. Will super-intelligent machines need art? Probably not.

Rosa: As with audiences who experience your work solely online, do you think that something gets lost, intimacy perhaps?

Anicka: Yes, in so far as when experiencing the work in person, it’s a symbiosis. You contribute to the

work, and the work becomes a part of you. It’s a takeaway. That artwork becomes a part of you as well, whether you like it or not. The symbiosis is so fascinating to me, and I try to foreground that. I’m not trying to essentialize the real-time experience, but, so far, it’s pretty powerful and important to me. With that being said, the increasing digitization of life is something that I’m thinking about currently.

For Grabbing at Newer Vegetables, included in Yi’s exhibition You Can Call Me F at the Kitchen in New York, Yi asked 100 female acquaintances to swab their microbe-rich orifices, before culturing the samples, resulting in green-brown growth used to paint and write on an agar-coated surface set in a glowing vitrine. The final work is said to have been overwhelmingly pungent, with notes of cheese and decay, both corporeally familiar and sensorially challenging. Yi created the work during her time as visiting artist at MIT’s Center for Art, Science, and Technology in 2014–2015. Rosa de Graaf

Rosa: You’ve identified before, that the West has become overly dominated by the ocular sense, sight. Everything is about looking, resulting in what you’ve referred to as ‘ocular fatigue’, which impacts how far we actually look. The image comes to us, rather than the other way around. Outside of your practice, how do you go about reducing ocular fatigue?

Anicka: Yes, I’ve been limiting myself to just ten, fifteen minutes of social media a day. I just can’t look at that much. I think that it’s simultaneous with the degradation of your senses. My vision is starting to degrade, and I’ve been very lucky for all my life to have perfect 20/20 vision, and yet still I hated looking at things. It becomes more painful to use my eyes so I’m limiting myself a little bit more, but also, I like analogue visuality a lot as well. I like to read books, paperback, and hardback books versus screen-reading and things like that. That is symptomatic of having ocular fatigue, I believe, you know, because something about screen-reading does something to my eyes that is not sustainable, whereas I can read a book for much longer.

Rosa: Your work has often been described as bio-fiction. What’s the role of narrative in your work? Where does it come in?

Anicka: The narrative has mostly been the springboard. While I’m definitely attracted to and inspired by materiality and texture and form and all of those things, maybe I’m not confident enough or skilled enough to build something just completely solid based on that. It always has to just sort of come from this germ of the narrative. Without it, it becomes a more procedural, potentially didactic relationship that I might have with the material, with a medium or a technique. That’s something I’m not really allowed to do. I’m not allowed to make didactic work, and I’m not allowed to prove a hypothesis for you. These are the limitations that I set for myself.

Rosa: Revisiting your work The Flavor Genome time after time at Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, which sees a commercial flavourist on the hunt for a mythical orchid, I wonder where you harvest your narratives from? What led you to embark down the trail of the flavour genome?

Anicka: That has been percolating and brewing for, I’d say, a long time, at least a decade. And it was a very, absolute, just ecstatic joy to be able to articulate what I’ve been scratching at for ten years and not really being able to articulate. And so, in a way, it is some kind of euphoric, resounding sort of shout, that… I don’t know. This is one of these instances in which elements are seeming to coalesce together, and it felt like probably the first project that I’ve done where I was reflecting much more about my body of work, and what I’ve been trying to understand, what I’m trying to investigate and explore, rather than just trying to forge on to the next paradigm or something.

…Imagine, as a penance, that your own natural body odour would be some kind of indication and evidence of your sins…

Rosa: Indeed, the coalescing of elements such as race-, class-, and gender-based associations of scent, or flavour more broadly. How does this coalesce into what you’ve described as a ‘biopolitics of the senses’? What do you intend by this?

Anicka: Just to reiterate how our senses, and the perception of our senses, are shaped and conditioned and charged politically, and how we disassociate these biological drives and their biological mechanisms, and we think that they’re just ‘natural’. And of course, they’re not necessarily natural. We have interpretations of them, including how much, over the history of humanity, these different sorts of narratives have influenced how we relate to our senses.

So, for instance, how much did Christianity play a role in the repression of smell, for instance, and how did religions, different religions, have different relationships to smell? So, you had the height of the Roman Empire, everybody – not everyone, exactly, but a lot of people – were very much steeped in the perfumes and the oils, and even the impoverished had a little bit of access to that. And then the Christians came along, and they said, no, absolutely not. Imagine, as a penance, that your own natural body odour would be some kind of indication and evidence of your sins. They banished the perfumes; they banished the fragrances. And we were relegated to having our own natural odour as the prominent smell. But that was also perceived as something that is related to sin and blasphemy and a very negative relationship to the body, to that which is biological.

Rosa: As for today, what conditions or associations are you currently seeking to reconfigure through your work?

Anicka: I’m thinking a lot about how, throughout human history, these fictions and myths have constructed the civilization of our societies, and how we’re able to cooperate with each other around these myths that in the twenty-first century are entering a new phase of human; that we may be exiting the sapient phase.

Rosa: Is there a place for vulnerability in the arts?

Anicka: I hope so. Yes. Constantly. I think on a very practical, almost remedial level, art is about communication; it’s also about building relationships, right? And it’s just overloaded with vulnerability, when you’re dealing with building relationships. But then there’s also this promise of cooperation. And how is it that we’re able to cooperate and transmit? And I think that art is very much steeped in a lot of that kind of… There’s a kind of mythology around it, that we believe. Because without belief, a urinal is a urinal, right? We endow that, and that ties into consciousness. We create meaning; we give the meaning to consciousness; consciousness doesn’t necessarily have meaning in and of itself, independent of us giving it meaning.

Rosa: Is this what drew you, as a self-trained scientist, to begin producing work within this context? The domain of art, that is.

Anicka: Well, I think to some extent I’ve always known or suspected that I had a very peculiar syntax, and that, probably, there are not a lot of systems in our world that would allow for someone with my kind of peculiar syntax to flourish and communicate. But knowing that, my neurosis was also very stubbornly resisting it, so that’s why I came into art later in life rather than going down the path that most people take, as in, ‘Oh, I’m interested in something, and I have a strong desire, so I will get the necessary training and the necessary tools to embark upon this path early on.’ For me, I had a very circuitous journey, and I was deferring this – I don’t know what you want to call it, this eventuality

or something – for a long time, because the thing that you want the most sometimes is the thing that maybe you’re afraid of, right?

Rosa: Absolutely.

Anicka: So it took me a while, but I think I had a hunch that, having this peculiar syntax, probably the community known as art could somehow, maybe, allow me to gain entrance.

Rosa: Do you find the peculiarity of your syntax accommodated within the role of the artist, or are you somewhat more

of a hybrid?

Anicka: Yeah, I’ve always felt like an outlier. And I think that also comes from having been brought up in a hybrid culture, right? You know, my

parents trying to espouse this Korean ethos, and it seems very abstract, because I didn’t grow up in Korea, and I wasn’t steeped in the Korean community in the places that we were living, and that I grew up around, and so it was kind of a single source. It’s kind of like you just have to trust that what they’re talking about makes sense, which it often didn’t. And so, this hybrid sensibility feels very natural to me, but also yields a lot of conflict.

Rosa: On conflict, in parallel to your practice, you’ve also been a very active voice in feminist activism, as an initiator of the ‘Not Surprised’ movement, which shared the concerns (and extended the momentum) of the ‘Me Too’ movement, only specific to the art world context. How fertile, for you, is art as a tool for social justice?

Anicka: It seems like it just goes hand in hand. Maybe it’s not as self-evident as it feels at times. I think a lot of what art is, is precisely what philosophy can’t do. We can create a physical manifestation of a certain kind of ethics, or at least an ethical line of inquiry. And so, it just feels like all that would necessitate is the extra steps towards, or bridging bubbles from the art to the social street. It feels necessary. And that’s not to say that the artwork diminishes if the person – the artist – isn’t an activist. But I think we’re living in a moment, especially with the Not Surprised and the Me Too, in which it is not enough to just make art about something conceptually, and build your art identity as a feminist, and then hate women, or be a rampant misogynist in practice. I know examples of that in the art world. And so, I think we’re living in a moment where people seem to

be looking a little bit deeper into

the very identity around one’s work and how it extends or bleeds into one’s practising life.

Rosa: What are you currently most intrigued by?

Anicka: I’m intrigued by… I’m intrigued by… I’m intrigued by a lot.

I’m intrigued by how we’re going to change as a species, and what it’s going to take, and how we probably aren’t going to get there. But we’re going to change nevertheless, and it may not be the way we want it to be. So, unfortunately, it’s an ending with a little bit of a dystopic flavour to it.