I didn’t know I was moving to New York in June 2001, but that’s what I did. Freshly out of the closet, obsessed with movies, and desperate to escape a small town, I was the prototypical New Yorker who just needed to get there. Halfway through the summer, I had a boyfriend and a job and I knew I wasn’t leaving. I still haven’t. A month after arriving, friends took me to see a new film called Hedwig and The Angry Inch (2001). All I knew was that it was a rock musical about a botched sex change operation and that it was the brainchild of a downtown actor named John Cameron Mitchell. My cinephilia had studiously avoided musicals for no good reason, so I was overdue for a real introduction.

A fucked up fairy-tale about an outsider who falls for the wrong person and makes art out of her pain, Hedwig was the perfect movie for any emo queer kid who wanted to be an artist. Its DIY aesthetic made other indies look slick and corporate. Here was a film that wasn’t afraid to let the seams show and the make-up run, as long as the emotion was real.

John’s performance as the ‘internation-ally ignored’ diva stranded in backwater America blended Bowie, Iggy Pop and Rocky Horror into something original and genuinely moving. Belting out Stephen Trask’s glam-punk ballads, Hedwig convinced me I had been harbouring a secret love of musicals all along. And the film’s final shot with Hedwig walking naked and alone down an alley was seared into my hot, humid brain.

It was still on my mind three years later when I stopped at a West Village cafe and sat down at a communal table. I pretended to read my Village Voice and not notice that the cute guy sharing the table with me was John Cameron Mitchell. When my sandwich arrived, he looked up and asked if it was good, which I thought was funny. He was typing on a laptop so I asked him what he was writing. It turns out it was Shortbus.

John’s 2006 follow up to Hedwig is an offbeat portrait of sex and intimacy in post-9/11 New York that features lots of unsimulated sex. A depressed dominatrix craving connection services finance bros next to the WTC site; a gay couple in crisis (Paul Dawson and PJ DeBoy) open up their relationship; a therapist (Sook-Yi Kim) is on a journey to finally – just finally – orgasm. An art salon called Shortbus and MC’d by Justin Vivian Bond serves as the film’s social and sexual locus. Had I not been shy, I could have been a ‘sextra’ in one of the group sex scenes.

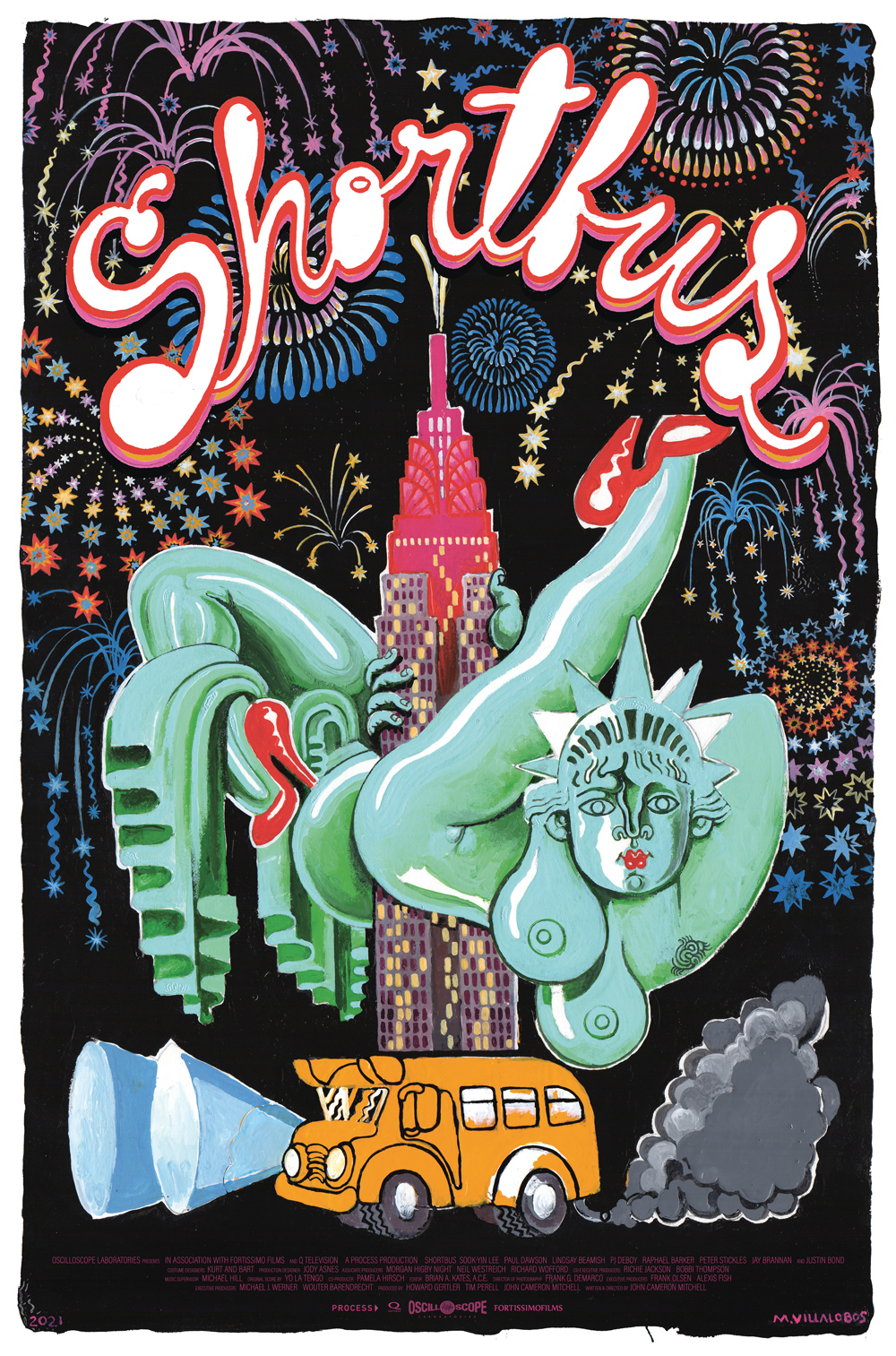

Sixteen years later, I am now the same age John was when he made Shortbus, which in 2022 debuted as a new restoration, followed by the release of a new special edition DVD/Blu-ray by Oscilloscope Laboratories. I now see it as a document of a particular moment in 21st century New York when an ‘underground’ – a gender-fluid zone that mixed sex and movies – still seemed plausible. Shortbus may be a love letter to a lost time, but its determinedly optimistic vision of 1960s-infused full-spectrum liberation feels just on time for today.

Shortbus, 2006. Courtesy of Miguel Villalobos

Paul Dallas: We’ve been in a pandemic for over two years now. I wanted to start by asking how you’ve been.

John Cameron Mitchell: Everyone, for a minute at the start, enjoyed a break if they could. And I liked the break. I was in the middle of my Hedwig tour, so I stayed in California. I did some online shows which were fun. An ex of mine runs the first LGBT soup kitchen in Mexico City so I was and still am raising money for him. Over the first year, I was in different places like Provincetown and Portland for the Hulu series Shrill (2019–21).

I would often get a big house so that people who were ‘Covid orphans’ could come and stay. They were like halfway houses. It was nice to be out of New York too. In the last few years, I’ve fallen out of love with the city, and the pandemic probably exacerbated that. I kept going to New Orleans, which is where I ended up buying a home. I also worked on an adaptation of Neil Gaiman’s Sandman (2022–) for Netflix in London. I’m acting in it, which I did because the character gets to sing songs from the musical Gypsy (1959) – I want to play Mama Rose someday. But from there I auditioned for Joe vs Carole (2020–21), which was actually my first audition in twenty-five years, a self-tape. I really went all out to get the mullet. Then, after I got the role, I was in Australia for the rest of last year.

Paul: So you were very busy.

John: After the first six months, yeah.

Paul: You came of age during the HIV/AIDS crisis. I’m curious if you saw connections between that crisis and the pandemic.

John: Obviously it’s not the same thing but there were some weird parallels. In the COVID-hoax and anti-vax communities, I saw echoes of gay men who had similar concerns when AIDS hit. People who thought that the government was causing the virus. People who had the attitude, ‘don’t tell us to have safe sex, it’s a symbol of our rights.’ AIDS activated a lot of people and led to the modern queer rights movement. ACT UP was a model of constructive engagement, working different angles, engaging the drug companies, shaming officials, intersectional politics; fighting for people who were not just gay men. The idea of health care as a right came out of that. They had a very clear goal that groups like BLM or Occupy could have learned more from.

Paul: Let’s travel back in time. What brought you to New York?

John: I had been in LA for a couple of years. I was doing the underground stuff, going to the clubs, and then doing mainstream TV and theatre. It was fine but it just wasn’t my place. LA had its own queer underground led by Vaginal Davis, Ron Athey and my friend Billy Limbo – who had a fucked-up open-mic night called The Limbo Lounge. Bob Shaye, who ran New Line Cinema, directed me in a teen comedy – Book of Love (1990). When I first saw the script, I said to him in the audition, ‘It’s pretty homophobic.’ He was shocked. He said, ‘Well, no, it’s homoerotic.’ I was like, ‘A lot of words begin with homo.’ I explained why it was homophobic – the stupid paedophile jokes – it wasn’t even consistent in its parody or its stereotypes. He heard me and rewrote the script. But in the end, it wasn’t a great experience. I moved to New York right after that.

Paul: Then you starred in Six Degrees of Separation (1990), one of my favourite plays. Tell me about New York then.

John: The seminal NYC club Squeeze-Box! started in 1994. It was full of creative rage. It was my heaven on earth, watching all these punk rock drag queens. Stephen Trask – who would compose the music for Hedwig – and my boyfriend were in the house band. There was one female character who became Hedwig – she was the only one I could do at a drag club. Stephen encouraged the character to be the lead. The next four years were a cataclysmic time in New York. The life-saving HIV/AIDS drugs arrived in 1995. Rudy Giuliani came in as mayor and was, in his view, ‘cleaning up the city’ and taking credit for a drop in crime. New York was changing. I remember the first time I got thrown out of a club for smoking pot – I was shocked!

Paul: So you were toggling between these different spheres, the largely straight uptown New York theatre scene and this vibrant queer underground?

John: The downtown cabaret, theatre, music and film scenes of the 1990s were all separate but interwoven. There was always some version of that in New York. In the 1960s, it was Warhol and Jack Smith. In the 1970s, it was Charles Ludlam, Harvey Fierstein and the Tavel brothers. Interesting queer undergrounds that inspired the rest of the world. I was in those traditions, learning from them and carrying them forward. I was also bringing what I knew from uptown to downtown in terms of narrative and letting in the chaos – the rock and roll energy of Justin Vivian Bond, Vaginal Davis and Mistress Formika. Sherry Vine was my drag mother in a way. But I was also incorporating Plato and Gnostic Christianity – ancient drag. I combined the Greeks, Shakespeare and kabuki with modern drag – with Bowie and Little Richard and Lou Reed. I was pulling together all the things that I liked into one piece but not thinking about it in a commercial way. And I think that’s the healthiest way to create something new: just make it for you and your friends, and if it’s good, people will want to watch it.

Paul: I completely agree. So after Hedwig was born, you and Stephen continued developing the work which eventually became the theatre piece Hedwig and the Angry Inch.

John: We opened off-Broadway in 1998, which was a feat. Someone lent me a wig. I made my own costumes. I wanted a kind of 1980s German look because I lived in Germany when I was a kid. I was gathering together lots of things I knew, taking my time doing mainstream acting and then putting it into Hedwig. It became a succès d’estime. People who hate musicals started coming, and suddenly they wanted to make the movie. Bob Shaye, the guy who I had to talk to about homophobia, came to the show and was very moved. He said, ‘I want to give $6 million to this film, because you’ve always been direct with me and not in a hostile way and I appreciate that.’ I learned that if you react in a measured, kind way but don’t hide from problems, it can lead to good things. And the film was a flop. It lost half of its money. But then through the DVD release it made its money back and became a cultural success. I wouldn’t have it any other way. Too much success is unhealthy.

Paul: You had never made a film before and now you were going to write, direct and star in one. What was that like?

John: The Sundance Lab was really important for me to learn my craft. Michelle Satter, the great unsung hero of American film, really made me into a filmmaker. She paired me with Frank DeMarco, who ended up becoming my cinematographer. My advisors were Alfonso Cuarón and Gus Van Sant, just to have them there and to have Robert Redford give me a note about Hedwig. He said, ‘Remember the boy that Hedwig was,’ and I was like, ‘You’re right, Rob – Bob!’ So I had a lot of people helping me along the way. Then I had a year to develop the script and to talk about camerawork and the set with Frank DeMarco and Thérèse DePrez, who was the production designer, which was essential.

Courtesy of John Cameron Mitchell and Killer Films, New York. Photo: Miguel Villalobos

Paul: Given the conservatism of the American film industry, it’s still amazing that the film was even made. What were some of your cinematic references?

John: After I created the role of Hedwig, I saw In a Year of Thirteen Moons (1978), which is a Fassbinder film where the main character is forced into a gender reassignment operation. Although, to be honest, I was more inspired by the documentary I Am My Own Woman (1992) by Rosa von Praunheim.

I remember meeting Rosa in 1988, which was inspiring. Then there was Sandra Bernhard’s Without You I’m Nothing (1990) – which showed me that a musical could be anything – and The Black Rider (1990), a Robert Wilson piece with Tom Waits and William Burroughs. So my influences were far afield.

Paul: You won the Directing Award at Sundance. You were suddenly a hot commodity.

John: Bob Shaye at New Line was very proud of the film. He helped us get Golden Globe nominations. It was way too early to get any Oscar nominations because it was too weird, too queer. But after Hedwig, I did get a lot of offers. Hollywood tries to grab you and push you into something where you have less power.

Paul: And you said no.

John: I said no to everything. I got offers to direct Rent and Memoirs of a Geisha – things that people thought were splashy and queer. I was offered a role in the X-Men franchise. But I was old enough to know that the more money there is, the less control you have. I had my rent-stabilised apartment. I had low overheads. I didn’t feel the need to run after money. I wrote a children’s film with a friend, Julian Koster, from the band Neutral Milk Hotel, but it was weird too. And I started Shortbus. I grew up Catholic, which was one of the reasons I wanted to make the film, to challenge some of my own fears. Sex is like the brainstem to all parts of our nervous systems, to our bodies and life. The way a person has sex tells you something about them in a way that nothing else can. And it’s also ridiculous, irrational, funny, heart-breaking, boring. There are many stories to be told using sex.

Paul: You’re an avid cinephile and we share a deep love of Cassavetes and Altman. What were some films that affected your approach or your thinking about sex and desire?

John: There were a couple that were important to me. One was Un chant d’amour (1950), Genet’s only film, which is a little poem about men in prison and desire. It takes its time and is beautiful. The other one was Taxi zum Klo (1980). The film is pre-AIDS, autobiographical, set in Berlin. It’s funny, touching, melancholic and it says something. It centres on an elementary teacher who is gay. At the end, his two lives collide when he goes to an all-night drag-love ball party and his relationship is destroyed. It’s very much about freedom versus community or relationships. How do you negotiate them both in a homophobic culture? The ending is brilliant because after his life falls apart he’s still in drag and he goes to work the next morning. All the kids are totally surprised. It looks like a documentary, the way it’s shot. He says to the kids, ‘Today we’re going to learn about freedom. For the next hour, everyone in this room is allowed to do whatever they want.’ It turns into mayhem. It’s amazing. That tone informed Shortbus.

Paul: It’s a favourite of mine. Something was definitely in the air in the late 1990s and early 2000s because there was a return of graphic sex in art house cinema. There was Leos Carax’s Pola X (1999), Patrice Chareau’s Intimacy (2000), Michael Winterbottom’s 9 Songs (2004), Vincent Gallo’s The Brown Bunny (2003). The list goes on. What did you want to do differently with sex in Shortbus?

John: I think Catherine Breillat’s Fat Girl (2001) was the most successful.

I saw the pitfalls of getting too serious. I wanted to evoke a New York that had an Albert Brooks–Woody Allen–Hal Asby tone. Robert Altman was another reference, although he can be kind of cynical. He has affection for his characters but there’s always a little bit of distance too.

…There was a kind of sex magic which equated sex with art, community, food and drink – everything good in the same space. Stephen Kent Jusick’s salon put that into practice every week in New York. He’d show films on 16mm, serve vegetarian food and then there’d be some public sex…

Paul: This is what makes Shortbus so unusual. It’s ultimately an optimistic film, which isn’t always popular in art cinema. Can you talk about that social milieu that inspired it?

John: I had been influenced by going to the Radical Faerie gathering at Short Mountain, Tennessee, in 2002. That spirit of queer hippiness infused the project. I met people there who we ended up casting. There was a kind of sex magic which equated sex with art, community, food and drink – everything good in the same space. Stephen Kent Jusick’s salon put that into practice every week in New York. He’d show films on 16mm, serve vegetarian food and then there’d be some public sex. I’m not a group sex person but I was fascinated. So that informed the project too.

Paul: Let’s talk about the casting process behind this film – which uses unsimulated sex to explore different dimensions of intimacy and desire – because it was extremely unorthodox.

John: It was called ‘The Sex Film Project’ at the time. We wanted it to be democratic. I had an audition website, and literally anyone – friends, strangers – could send in a tape. About 500 VHS tapes were sent in. The tapes were already giving me story ideas. We chose forty of the people who clearly weren’t just in it for a pornographic thrill. I encouraged them to talk about an emotional sexual experience so we could separate what we were doing from porn, which is not known for its emotion, and I reminded them that we were going to write the film together. Everyone was part of the community and could weigh in on what the characters’ trajectories should be.

Paul: I remember the website. There was cum. Obviously, there were some risks casting non-professional actors too.

John: I told them, ‘It has to be a version of you. It’s not a documentary. You’re exaggerating parts of yourself.’ I encouraged the actors not to get together ‘after school.’ I couldn’t enforce it, but I said, ‘Save the fucking for camera,’ and of course they didn’t. About a year in, the financing collapsed, so it was hard. The actors were very supportive. Then the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation got wind of the film and was suddenly going to fire Sook-Yi. We solicited letters from celebrities in support of the project as art and not porn. In the end, they backed down. Yoko Ono, Michael Stipe, Julianne Moore and Moby were very supportive. Even Francis Ford Coppola, who was a big fan of Hedwig. I don’t know if he liked Shortbus. I remember he came to see it at Cannes and pronounced it ‘amusing.’ That was all he said.

Paul: The film features a lot of different kinds of sex. We have a dominatrix servicing bankers in the Financial District. We have a threesome that culminates in one character singing the national anthem into another character’s ass. And we have the titular salon ‘Shortbus,’ which features a ‘sex room’ each night with large orgies. As a testament to your faith in the project, you participated in the ‘sex room’ by going down on a woman for the first time.

John: Male and female energies need to team up, which is why I’m a big fan of androgyny. That’s the goal. Borrowing elements from what we might call male or female. We have to connect both. Shortbus is about integration. It was a reaction to the beginning of digital culture. The character James is making a suicide video instead of a suicide note, explaining through images how he feels and how he wants his lover to live without him. He adds a third person to the relationship so his partner won’t be alone after he dies. It’s insane but it’s in line with today’s obsession with self-documentation. That storyline was inspired by Jonathan Caouette, who auditioned for Shortbus with elements of what would later become the documentary Tarnation (2003).

Paul: Watching Shortbus again, I was especially entertained by ‘Yenta,’ the fake dating app that actually predates Grindr! You saw the future.

John: I invented Grindr in Shortbus!

I could have been a product futurist. GPS was happening and I could see that. I even asked my lawyers if it’s something I could copyright. I would have to have patented it. The iPhone arrived the year after the film was released, and then the apps started coming. Sadly, Grindr has become the gay bar. In one way, it’s good because it’s not alcohol based. But in another way, it’s bad because you’re not getting the full person. You’re slicing and dicing them into attributes. Capitalism won.

Paul: Shortbus premiered at Cannes in 2006. After four years of working on it, what was it like to finally finish?

John: It was a sensation at Cannes. We had a party on the beach and a concert with Justin Bond and we were all just rocking out. When the film was released in the fall, it was a moderate success. It wasn’t banned. We were hoping for a little more outcry. It didn’t really rile up the right wing because it was a different world pre-social media. Things weren’t stirred up the way they are now. Interestingly, many peers in the theatre refused to see it because they thought sex on film was porn. Theatre people are more conservative. But even progressives confuse sex with porn.

Courtesy of John Cameron Mitchell and Oscilloscope, New York

Paul: So there was a certain backlash.

John: A lot of people told me: ‘You could make a lot more money if you took the sex out.’ I could have also taken the songs out of Hedwig and it would have been something else. But that’s not what I wanted to do. We never had to cut Shortbus, but we did have to blur things for certain markets. You couldn’t show pubic hair, but you could show cum! It was all very arbitrary. In South Korea, Shortbus was banned. The distributor took the case to the Supreme Court and changed the censorship laws. What tickled me was that the Supreme Court of Korea had to watch the film. They said, it’s ‘distasteful’ but we had the right to show it!

Paul: It’s fascinating how the cultural landscape in the US has changed since 2006. Shortbus’ rerelease has predictably stirred up conversation about whether a film like this could be made today.

John: It’s a different time. When I say it couldn’t be made now, here’s an example of why. When I showed it at IFC Center in January 2022, the reactions were all great. The people who had seen it before felt more of the emotion this time because we’re more immured to the sex now. The young people, though, focused on whether someone was being exploited. They were looking for a reason to cancel it, but they couldn’t put their finger on what. There’s nothing to criticise – everyone was taken care of, everyone felt great. We were doing things that were ‘uncomfortable,’ but doing a fight scene is uncomfortable too.

People are on notice, which is maybe good. But walking on eggshells and not taking risks because they’re afraid of being shut down isn’t. And that’s another reason we don’t have subversive filmmaking. Where’s the David Lynch of today? Watching Happiness (1998) again was unbelievable. Todd Solondz struck a tone that no one has ever struck. The young kid cums and the dog licks it up, then the mother kisses the dog. It’s absolutely shocking. There are not many people taking risks anymore. It can all change again with one great movie. Even something like Parasite (2019) was a real outlier.

Paul: The lack of risk-taking in American movies is real. America has always feared sex, and now filmmakers are more scared than ever.

John: Shortbus was an antidote to the cynical porn of the day. It was a reminder that queer sex and queer life have lots of incarnations. And it was sex-positive without being stupid or sleazy. Now we’re in an era where Andrea Dworkin’s anti-porn rhetoric is back. And it’s like, really? Let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater.