A summer evening in the south of Antwerp. The actress is waiting for me under an awning out on the terrace. She is smartly dressed and possesses a clear gaze. I hadn’t expected her to be looking so good; so bright, strong, open. I feel awkward having to talk about eroticism to a woman that’s just lost her son, even if the woman’s an actress I’ve seen in so many different roles.

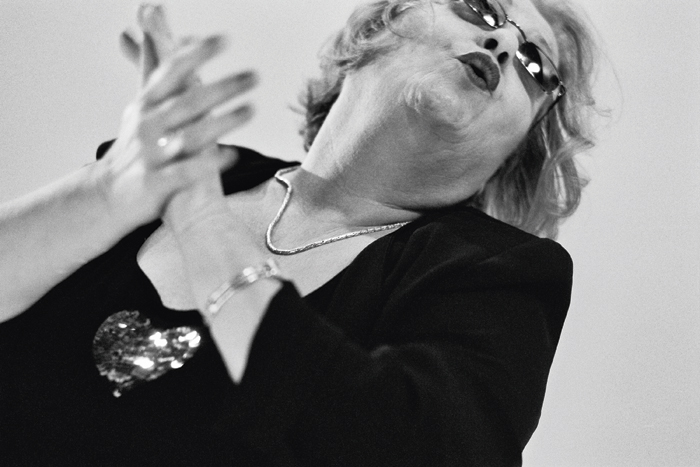

Viviane De Muynck impresses with a charismatic vigor. Her full-bodied stage presence is robust, and the roles she plays are varied. Each exudes a raw mix of strength and vulnerability. Viviane is the enigmatic narrator in Ghost Road, a road movie on stage, conjuring up the ghosts that still haunt the now disused Route 66. In the Needcompany’s performance ‘Isabella’s Room’, she takes the lead in a play dealing with themes of eroticism, power and death.

I order sparkling wine and bottled water for both of us as we prepare to talk about the great loves in her life, her husband and her son, both of whom she has lost. An encounter with transience, layered with intimacy and sensuality.

Oscar: Viviane, tell me how you’re doing.

Viviane: Of course it’s awful, someone suddenly being snatched away when you really weren’t expecting it. You think, my God, I miscalculated, the timing was wrong.

Oscar: Snatched away? What do you mean?

Viviane: If only he’d gotten to a hospital in time it would have been all right. But he thought, I’ll do all that when I get back to Belgium. That night he had a bad fall and died of an internal hemorrhage. I couldn’t get through to him for two days, and then I called the people at his work and asked where he was, and when they last heard from him? They said three days ago, and I said there’s something wrong! He isn’t answering my calls. Then we called the police in that little village and told them to kick down the door. If my kid’s in trouble someone has to help him. We drove there as fast as we could. He’d been dead for three days.

Oscar: Your son?

Viviane: Yes. My son, my soul mate, my only child. Michel. He was going to start work in an Austrian ski resort at Christmas and had just returned from Thailand. We aren’t the kind of people that stay chatting on the phone for hours. He was nearly forty-two, so you respect a person’s privacy. You don’t want to be of one of those mother hen types, but I guess that meant there were some things I didn’t see.

Oscar: What exactly happened?

Viviane: He’d fallen badly while he was out snowboarding, he’d hurt his shoulder and it kept on hurting, and he went from one doctor to the next, for nearly three weeks. Finally in the hospital they told him he had a torn muscle. He couldn’t work in the resort, where he had to carry trays and so on. I remember telling him just to make sure everything was OK…

Oscar: So the police broke down the door?

Viviane: You could see the smashed door and the police tape, and when the police got there the first thing I asked them was ‘Ist er noch am Leben?’ Is he still alive?, and they said you’d better come on down to the police station, and then I knew and my whole world fell apart, just like that. Next you go to the funeral home and you see your child lying there in a see-through plastic bag, no dignity, nothing, nothing, and I said I’d like to hold him in my arms, and they said I couldn’t because he was already starting to decompose. His face was black, one side of his upper body was all black from the fall that had caused the hemorrhaging. But the police told me the doctor had said it was a tragic accident, he’d died in his sleep, and you cling to that, the idea that he didn’t feel anything and that it seems all very quick because painkillers thin out your blood. Back in Antwerp I was able to give him a beautiful funeral with help from his friends. It was the last thing I could do for him, with lots and lots of music, his music. The people at the theater didn’t know he was a musician.

Oscar: What kind of musician was he?

Viviane: A jazz musician, a bass player. He worked with various groups, so he never earned anything much, and then he went abroad and always managed to make his way. It was a roller coaster, four seasons to a day. When Michel died I lost the only person who really loved me.

Oscar: But you really loved him too?

Viviane: Sure, you know, mothers and sons, we were so very close, partly because he was only six when his dad died, and of course I eventually got started in the theater and he followed it very closely. He saw nearly all my plays, except for a few times when he was out of the country. He always went on about my work with Discordia, that was his yardstick, and he was terribly proud of me.

Oscar: What about his father? Was he the great love of your life?

Viviane: His father was older than I was. He died young, only 48. He was basically someone I was great friends with. I was eighteen years younger than he was.

Oscar: Did he have anything to do with the theater?

Viviane: No, not in the least. He worked at Ford, in quality control, an engineering job, even though he’d never trained to be an engineer. He was really athletic. He used to be a featherweight boxing champion and a fencing champion, and was into martial arts. A really athletic man with an incredible sense of humor.

Oscar: Were you an actress when you met him?

Viviane: I was an amateur actress. He came to watch my plays, but he would always fall asleep. I would put him in one of the boxes and he’d wake up when he heard my voice.

Oscar: How come you wanted to be with a man who was eighteen years older? Did you find that reassuring?

Viviane: I don’t know, but at one point I thought to myself I’d really miss a man with such a sense of humor. People my age weren’t like that, they weren’t interested in me…

Oscar: Why not?

Viviane: Because it’s still like that … An old friend of mine that I was really in love with once told me tu n’inspires pas le désir…

Oscar: Really?

Viviane: Yes, really. My relatives in Britain thought I was lesbian. They gave me Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness, and when I read it I thought what the hell’s this… ha-ha. I’m not the kind that sets a man on fire with desire. I mean, I’ve experienced that now and again, but these were exceptions. And that’s real passion… Passion’s all very well, but I think it burns you up.

Oscar: But you do desire men?

Viviane: Yes, I still do.

Oscar: Was your son’s father the first man in your life?

Viviane: Yes. I was twenty-three at the time. I met him at work, when I was an executive secretary at the Ford factory. Our relationship was all blazing rows and slamming doors. He had a fiery temper, and maybe that made him seem younger than the eighteen year age difference might suggest. I know people who are old fogies by the time they’re thirty. His name was Gustaf, and everyone called him Staf. My son inherited his stubbornness along with his eyebrows and nose. And neither of them got to be old. Staf developed a brain tumor. It was all over in five months. His whole personality changed. He became even less predictable.

Oscar: You’ve survived two of your loved ones. Is there something reassuring about this; that you’ve experienced both of them right to the end?

Viviane: I guess that feeling of gratitude will come, but not yet. At first you think, Christ, why now? I hoped that when I went to sleep my heart would stop beating, because the grief’s too much, too immense, too inexpressible. I can talk about it quite lucidly, but it seems there’s still no link between up here (pointing to her head) and down there (pointing to her heart). There are people who say life goes on, you just have to get on with it, and then I think – as my son used to say – the only thing I have to do is die. And a friend said you don’t always have to be strong, because that’s my drawback; people cling to me. My drawback is that I’m always a tower of strength for everyone, including for my son. I’ve often helped him out of trouble, this wasn’t the first time and these type are tough nuts to crack. When my husband died I went to music school. I worked for another six months, then I thought I’ve got to do it now, if I don’t do it now next thing I’ll be sixty and I’ll always regret it, and then I managed to reinvent myself, after his death, partly through the theater. It was only then that I turned professional. But how I’m supposed to reinvent myself now that my son’s dead, at this age, I’ve no idea.

Oscar: So why not act?

Viviane: That’s hard right now. Good theater has always got something to do with death. It’s confronting, passionate, you go looking for things, but at this moment you don’t have the guts to use things even unconsciously, which is what you always end up doing. I remember how it was when my mother was dying. A few days before she died I said ‘That thing lying there isn’t my mother’, then I went out into the corridor and I thought: the terrible thing is that I’m going to end up using this. When I had to perform in The Deer House in Nice just after Michel’s funeral (it’s about a child who has died), that was really very hard. I did it. I’m a professional. But I’m glad it’ll be a while until I have to do anything again, and then it’ll be something quite different. I want to do more with music, work with musicians, sing a bit, that kind of thing.

Oscar: Tomorrow you’re off to Crete.

Viviane: Yes, I’m going to Agia Galini, a small southwestern town on the Libyan Sea. My son worked there for many years. A Dutch guy had a bar there, The Milestone, with a small stage. The guy was also a guitarist, so the two of them would perform in the evenings. I often went to see him there, and I know the whole town. He was almost more Greek than the Greeks. I’m going to pick up his Yamaha Six-String, I’ve also got his keyboards, a Hammond organ and three basses, one of which was specially built for him.

Oscar: So you’ve got all his instruments. Basically what you’ve got is a band, without the players.

Viviane: Yes, but I’ll find the players.

Oscar: Are you going to stay there for a while?

Viviane: I’m going to Crete to mourn, I’m going to be Zorba – Zorba the Greek dancing on his son’s grave and shouting that he has every right to. I’m sure Michel has left a few small debts here and there. I’ll look the people in the eye and say ‘How much?’ I’ll pay all his bills for him. I’m going to stay at the same small hotel, it belongs to an old lady, I called her and she said ‘How’s Michel?’ and I said ‘He’s dead’, she said ‘My husband too.’ And then I’ll go swimming with her first thing in the morning, dressed in black.

Oscar: Did your son have a wife?

Viviane: No! Or, well… yes, he did. That’s a hell of a question… No, he didn’t actually have a wife, but he did have a girlfriend in Austria, but then after four years they broke up, and he never really got over it. He really loved Asian countries, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam. He’d known someone in Laos for three years, I had no idea, but in February she phoned him to say she was pregnant, and he called me about it. He didn’t know what to do. It wasn’t really a decision they made like ‘let’s do it,’ it was more of a wonderful accident. So now I’m in touch with her, and the child will be born in September, a girl, my first grandchild if everything’s as it should be – but I have to make quite sure about that. Sometimes I think, you stupid bastard, now you’ve gone and saddled me with something else…

Oscar: Perhaps he’s given you a present.

Viviane: Yes, perhaps he has.

Oscar: Has there ever been another man in your life since his father?

Viviane: I’ve known some other men, three or so, but I always kept them at a distance. I didn’t want anyone coming between me and my child.

Oscar: You say he was torn between you and the world.

Viviane: We were always very close, which is why I think it’s so stupid I never noticed. Sometimes he had what he called his downward spiral, which is why he loved those lines of Yeats that were on his in memorial card: Turning and turning in the widening gyre; the falcon cannot hear the falconer; things fall apart; the center cannot hold. I knew that feeling of his, but this time he couldn’t pull himself out of it.

Oscar: Do you believe in anything?

Viviane: I believe that energy is never lost, that nothing in nature is ever lost. But I don’t believe we all meet up again after we’re dead. I do believe that the essence of energy is turned into something. As long as you still think of people, they’re still there. But these things that make up my family will end with me, the blood line will trail off and these little bits of our line will cease running around somewhere.

Oscar: Do you ever feel happy for a while, and if so does that surprise you, or do you just feel pain?

Viviane: I remember the day after I’d seen my son dead. I was at the funeral home. I walked into the entrance hall, and there was this huge plant and I took hold of a leaf, and the guy said ‘it isn’t real’ and I said ‘yes it is, I used to have one just like it at home, isn’t it lovely?’ Then I looked at him and said ‘funny how I can notice such things at a time like this,’ and the guy said ‘just keep on doing that.’

People would come up and touch me without saying anything. And men who were eating would drop their knives and forks and shout; ‘We love you, Isabella!’

Isabella’s Room by Jan Lauwers & Needcompany

Oscar: In everything you say there’s a sense that life keeps on moving and you have to keep on moving with it. Maybe there’s something erotic about that, I’m not sure. How do you see it?

Viviane: I was thinking about that too, because we’re talking about the whole business with Michel, and I do ask; what’s the difference between eroticism and sensuality? Eroticism always seems to have purpose and sensuality doesn’t. I remember doing a grand tour of Europe, visiting the Venice film festival where a film I was in was being shown. After Venice we went on to Naples, Ischia, and then Rome. It was the first time I’d been to Rome, and Rome’s just so incredible. Of course we also went to St Peter’s, and you go in and turn to the right and there’s the Pietà, and I remember crying, tears streaming down my cheeks. My friend took a photo of it, and to me that’s really a very sensual picture. Embracing death is also sensual, but you have to be able to do it. I wasn’t holding my son’s hand when he died.

Oscar: But you did hold his hand.

Viviane: Yes, but only figuratively and that’s not the same thing. You can’t fathom the depths of someone’s soul. My son and I were so very close. It was a love affair without the sex. So there was something careful, something cautious about it. We had our fights too. I’m not easy to get along with, neither of us are. It isn’t easy being my son.

Oscar: But a child’s the result of sexual union with someone. A child carries that feeling inside him. Was he a love child? I mean, was he born out of love?

Viviane: Certainly.

Oscar: Is the word sexuality an important word?

Viviane: Yes, of course, when you’re young it’s very important. But I’ve always had a very negative image of myself. On the occasions when it did happen I couldn’t see it. It was a kind of blind spot. Maybe it was fear. Fear of totally losing yourself in someone.

Theater’s about real seduction, here and now.

Oscar: I thought women were supposed to be so good at that.

Viviane: Maybe there’s a masculine side to me. I was born just after the war, in 1946, with parents who’d been through a tough time, and we put all our energies into getting the country back on its feet, you just had to do it, just get on with it, so there wasn’t much room for flights of fancy. All that thinking and euphoria had led to such dreadful things. Of course there are the times in your teens when you suddenly burst into tears and don’t know why and then you see those New Wave films, those Italian New Wave films. My father was an ordinary man, but we would go to the movies every week, and on TV we’d see all the stuff by Antonioni, De Sica and Fassbinder, with an introduction by someone, because back in those days TV was still trying to educate people. Movies are more sensual than theater. Theater’s more erotic. Theater’s about real seduction, here and now. When I was awarded the cultural prize in Flanders, Jan Lauwers said, ‘She’s just like that Janis Joplin quote: on stage I make love to twenty-five thousand people, and then I go home alone.’ Eroticism magnifies things. It’s all about tones, Helmut Newton’s poses… showing these things sets people thinking, they put their own ideas into that image, that body… I think Isabella’s erotic or at least a vivid metaphor for eroticism. People watched it, and through me they saw themselves at various stages in their lives, and re-experienced that inescapable searching for someone. I guess that’s erotic.

I like touching people, there’s something sensual about it, and there’s no need for a climax. It isn’t meant to be erotic. It’s a way of being in the moment. You need someone who feels connected to you in the same way at that very moment. People can be shocked if you show that… Most women can act as if they’re totally uninterested, but I can’t. Men want to be hunters. A still unfulfilled desire, that’s what eroticism is to me. A promise. Eroticism’s outside you, sensuality’s inside you. Sensuality’s slower. Eroticism is, longing for, climax.

Isabella’s Room. Isabella’s Room by Jan Lauwers & Needcompany

Catharsis is in the audience, not in you. I experienced that in Avignon after my performance in Isabella’s Room, and I thought: now I know how a rock star feels. People would come up and touch me without saying anything. And men who were eating would drop their knives and forks and shout ‘We love you, Isabella!’”