A conversation about sensuality in contemporary dance can easily slide into platitudes. We might picture bodies, either cloaked or half naked, crawling and contorting their way through a choreographic maze. Therefore, in my exchange with Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, we challenge ourselves to re-wire some of this thinking. The work of the dancer and choreographer moves through and beyond the cultural tropes of sensuality and approaches the material in unexpected ways, permeating dance styles and cultures that deviate from what is considered to be contemporary movement.

Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, the iconic figure of daring in multiplying dance forms, reverted to Latin and mathematics in high school, and the flavoursome neo-soul R&B tunes of the 1990s as he gradually discovered that through movement the body opens up, and so did his consciousness, sensations, creativity and vision. For Sidi Larbi, movement became the pathway to worlds undiscovered. By attending Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s dance academy P.A.R.T.S. he was acquainted with the work of William Forsythe, Pina Bausch and Trisha Brown. Until earlier this year, he was the artistic director for Opera Ballet Vlaanderen, before taking on the artistic direction of Le Grand Théâtre de Genève. Sidi Larbi has also choreographed Broadway musicals, popular music videos and several Beyoncé shows. Above all, his work underlines the versatility of his craftsmanship, which is hard to pigeonhole. Within his practice is the pervasive notion that identity can be a dangerously normative concept, which he consistently aims to deconstruct and rebuild. Framed, you are labelled a type and part of a community. We decided to begin there, to find sensuality in the collective.

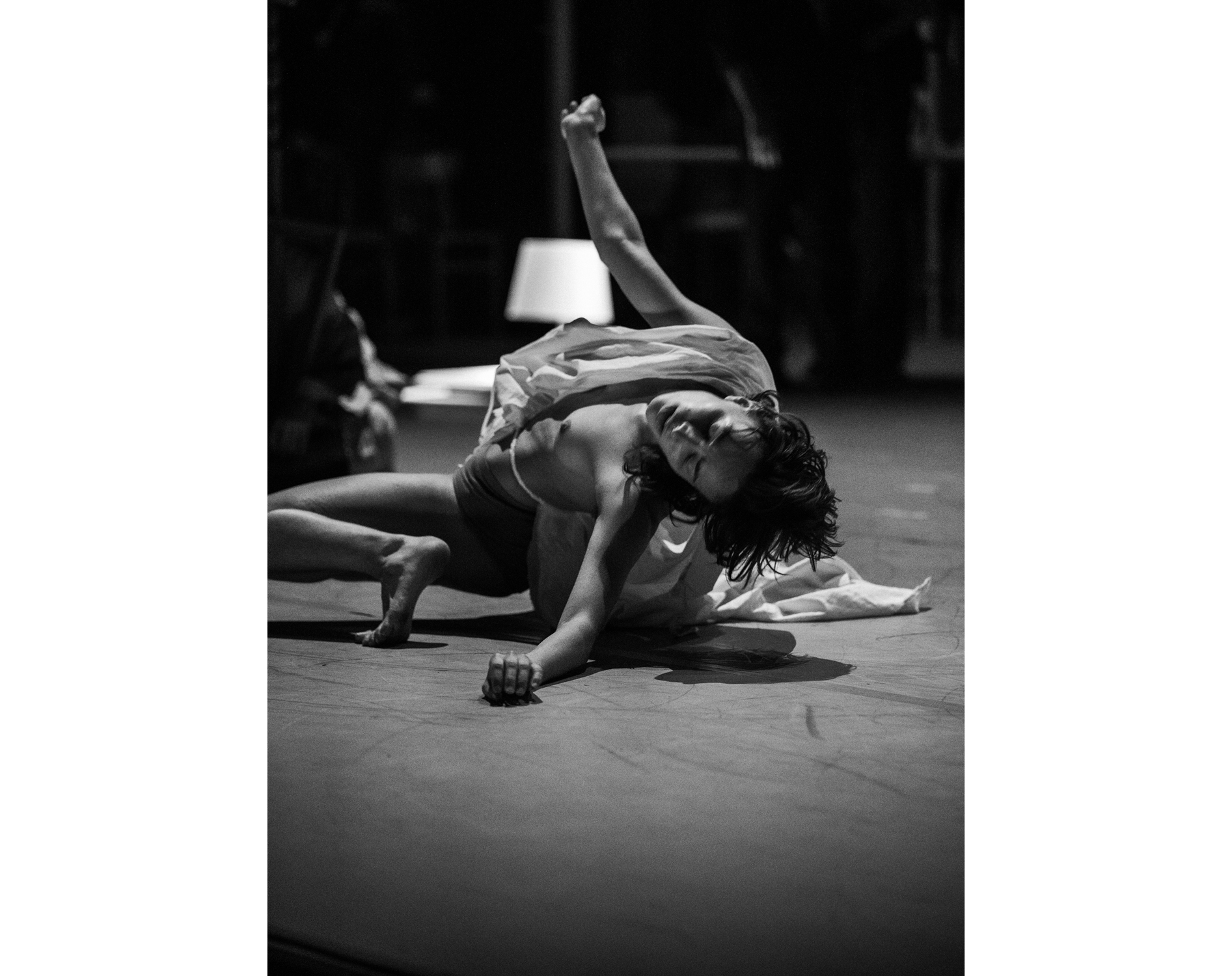

Babel (Words), 2010. Courtesy of Eastman, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui. Photo: Koen Broos

Judith Vrancken: I want to start with an obvious question, in the context of sensuality. Your work evokes a spirit of togetherness, and there is a friendship and symbiosis in the way you organise space and the collectives that you work with. Nomad (2019) is a clear example of this, because it comes from all these different angles – the music, the singing, the cinematography and the choreography. It made me think of sensuality as both being a collective and an individual practice. Noetic (2014) lands on structures of community and connection as well in the fragility between the performers on stage and their bodily extensions through the rings. I am curious to know how sensuality speaks to you through your work, and how you actively employ it within your practice as a choreographer but also as a dancer.

Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui: Well, the word ‘sensuality’ houses the word ‘sense,’ as in the senses. So, what we consider sensual is actually a form of connection we have with our senses. You are absolutely right in saying that sensuality is omnipresent in my work, specifically because it is an ode to all the ways we can exchange, or interconnect. There is this deep-rooted desire for connection that is part of my journey, mostly as it feels so absent in everyday life. What I have been looking for as an artist is confirmation of the desire for places that allow connection, spaces that make that feel necessary, or even expected. Whether that is the studio, stage or discotheque – because let’s not forget I was a go-go dancer in clubs at seventeen years old. That is what attracts me to different dance genres, like hip-hop or tango, to take two extremes. They are linked in this search for connection through the senses.

I find it a difficult and delicate subject because we are in constant combat with our social education. What you learn through your parents, and how family has a way of claiming your body. When meeting other people, there are resistances in terms of how you are supposed to act, depending on the culture you are from. I hate that word ‘culture’ – it’s more about where you find yourself geographically. So, let’s say in Switzerland, they give three kisses to say hello. I like that because it is similar to France where it’s two, or Morocco where it’s many. People really give a lot of care to one another. There is something very interesting in these codes being so different in different places. Dance offers space to negotiate these codes. My contemporary education was very much based on contact improvisation, in which touch and the sharing of weight was at the basis of every interaction. It gave me tools to be able to grab someone’s arm without hurting them and making sure that they feel comfortable. So now, when I collaborate with dancers, I invite them to do the same, and explain how they can be subtle in their physical exchange of handling weight, and what are the parts of the body that can bear your own weight, but also the weight of someone else. This is a very symbolic act, you know, carrying someone or knowing how to let someone carry you. Just by using these words, we are already imagining a form of psychology that is linked to this idea of being heavy for someone or being light for someone. I am not referring to someone’s actual body weight but how you hold yourself when you are being carried. I am really obsessed with that. When I am working with dancers, I’m sure I must irritate them when I talk endlessly about their weight-shifting moments. Shape isn’t always what matters to me. What matters is where the weight is, because when the weight is at the right place, it moves me, because it pulls me where I need to be. For it to be an incredible physical experience you must really commit the weight to where it can go. I think it is very sexy when something is right where it needs to be, when things fall into place. As a choreographer, I want to say I like surprises, but in reality I like to organise surprises and to feel relieved because I know what’s going to happen. Then my sense of memory and anticipation work towards that entity. For example, it is reassuring to know when the beat in the music drops. I like to reassure myself through choreography, to place everything. This is not a desire for power – it’s a desire for knowledge, and knowing ahead when things will happen.

Nomad. Courtesy of Eastman, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui. Photos: Filip Van Roe

Judith: I think it gives people a sense of agency to become a part of something. They can negotiate and anticipate their own role within the work and how to use it. It becomes this very personal thing. That’s why I love your idea of bearing weight alone and collectively, and I want to understand it correctly, because I don’t think you’re talking about balance.

Larbi: Balance is overrated, especially the perception of balance as a way to find stability. It’s the opposite. Balancing requires constant movement and reorienting; stopping would be dangerous. Instead of finding stability, we have to find alignment, as a place where we are constantly resetting things, every single vertebra.

Your brain pumps along with your heart. I’m very conscious of those beats and how all of us tend to suppress our inner pulses, both in ourselves and each other. We’re very heavy on each other’s behaviour. Don’t do this, don’t do that, straighten your spine, as if we are constantly putting little wrappers around us. Listening to these impulses of life inside of us has an impact on your articulation in the world. I used to have a very acidic stomach; it literally pulled my spine together. So, I had to work on my stomach, to align my spine. This problem was linked to a form of stress, which is linked to my psychology, my way of handling reality or handling people’s words. Even a simple word does something to my head, which does something to my stomach, which does something to my back. We exist in a reality where words can literally put us into knots, and we have to find the words and ways of moving that can take us out of these knots. This year, I have been talking a lot with the dancers about unravelling the nervous system. Think of your body as a nervous system rather than a collection of bones and skin. The nervous system is constantly stimulated by exterior circumstances, like cold, or pressure, but also the way we hold a piece of paper or a phone. All these things have a continuous impact on the way our bodies pulse, and in turn how we present ourselves to the world. Even though the support system of muscles and bones holds elements of our body together, we are much more than these structures. To move from this fluidity, rather than from the strict outlines of our muscles and bones, is where subtleties in the body can be found.

Judith: Thinking about how the internal manifests in the external, would you say that also works the other way around? Nomad, for instance, reminded me of the idea of landscape as body scape, where the surroundings become the representation of our internal, individual experiences. And I was wondering if what you just talked about also applies to how your environment informs and reflects the movement within your own body or within the bodies of people that you work with.

Larbi: The complexity of my practice is that we work a lot with the imagination. It is not like a Pina Bausch piece where dancers literally throw water on each other followed by an overwhelmingly real physical reaction and finding ways to dance through it or against it. Nomad has to do with imagination. On a video screen on the back wall everything is suggested like a painting. The back canvas features constantly changing painterly visuals of a desert landscape, gradually altering from dry, crumbling earth to soaking wet thunderstorms and from sleek blue skies to nocturnal black. Stars start dripping down and become rain. I wanted one physical reality to transform into the next into the next into the next. For Nomad in particular, I was interested in the idea of having to adapt to one’s environment, but through the imagination. If it is too warm, or too cold, too wet, too dry or too windy, the physicalities that the dancers emulate are linked to their imagination of that particular sensation. It is on the verge of mime. When we watch the work, the dancers seem to be pushed by strong winds or to collapse from the heat, so once the rain starts falling on the screen, there is a collective sense of relief and gratitude for this biblical cleansing. It brings an audience into a form of prayer. All of those things are immediate reactions to the external, which is interesting because it goes back to the roots of not knowing what’s coming. Nomad is full of little stories that come with a specific physicality. I worked very intuitively and would submit these characters to whatever the environment was throwing at them.

We so desperately want to know when and where we will end up, how we are going to die. Against that is the wonder of the unknown, when things are experienced on the spot

I think in our society we tend to grow up with a certain degree of control. Tonight I know it will rain because of systems of prediction that allow us to prepare. We so desperately want to know when and where we will end up, how we are going to die. Against that is the wonder of the unknown, when things are experienced on the spot. People who like my work tend to value that element of the unfamiliar. In Noetic, I remember people appreciated the transferability of things, when sticks became circles connecting to a bigger structure. I like the fact that one thing could become another and another. In the beginning, women wear dresses and high heels, while the men wear suits, assigning the dancers to a specific gender and to play the game of the binary. Towards the end, subtle shifts emerge; a male dancer wears high heels, two women dance in suits, and one or two men are in dresses. I wanted the audience to barely notice because the binary is there to be utilised by all of us in any which direction we want. That is me being a little bit subversive, especially when I’m having to deal with dance companies that are trapped in a binary system. After seven years of being the director at the Royal Ballet of Flanders, I recognise that everything in the institutional dance world is highly organised; fluidity or anything that challenges the border is often evaded, and that happens to be where I usually exist.

Judith: This fluidity brings me to certain movement qualities in your work. I can only describe it as dancers who, either together or alone, revolve around their own axis, emulating a liquidity and a softness that is very prevalent. How do these elements of softness show up for you in your work?

Larbi: There is a real desire to spiral, to go with the flow of movement. But I wasn’t always like this. When I was younger, I was much more of a funky dancer; very sharp, everything was angular. My dancing was a fight with the air around me, punching and rhythmical. By going into contemporary dance, I was so lucky to study with Dominique Duszynski, one of the dancers of Pina Bausch, and she was constantly inviting me to be softer, to a degree that she would be irritated by me. Eventually, I realised that underneath all those angles was someone who wanted to flow, who really desired to breathe, to glide. Every year I would go to Broadway Dance Center in New York, to study with Michèle Assaf and take these extremely specific jazz classes. They were full of musicality and technique. In the beginning I was always in front, showing off my high legs, but as I progressed through those years I slowly moved to the back. I realised that this urge for high intensity was over; I was elsewhere in my personal value system. It is impossible to keep that energy level up in a one-and-a-half-hour work, or a three-hour opera. It eventually exhausts itself, the dancers and the audience. In the work I do now I am much more aware of the sustainability of energy; what can potentially be exhausting to watch, what calms my brain, what is the pace that I find acceptable in order to be pulled along.

Judith: How do you evolve the audience’s presence within the work? You seem so aware of finding ways to draw them closer beyond their viewership, to create room for response and agency.

Larbi: Yes, that is a good question, albeit a difficult one to answer. In some pieces, I certainly break the fourth wall, sometimes by ways of speaking to the audience. Take Fractus V (2015), a piece for five dancers, including myself. At some point, I speak on the importance of letting go of worry, loosely based on a text by Alan Watts, and something I wanted to apply to my own work. It felt like performing an exercise with the audience, almost like a TED talk. By the way, in the last ten years I think I used about five TED talks in different works because I find them to be the ideal theatre texts, a true embodiment of contemporary speaking. I have also used texts and poetry by Kae Tempest. When you speak their words aloud, followed by dancing, the movement becomes a silent reflection of what was just said. It makes you perceive dancing differently, as if the words start floating around the movement quality. It’s the same with song – I use many singers in my work. In order to be able to generate that kind of sound, vocalists need to have access to all movement within their body. It is another way to break open an audience’s emotion since it invites them into another level of bodily awareness.

People often ask me why I frequently use objects. Just like the voice, objects can amplify the body; they make it possible to move the entire space. Choreography then becomes architecture. When dancers move in between those structures they become and create their environments. They decide what they live in, what it looks like before they step into it. As a choreographer, I can use my imagination to propose what the formation is and what it represents – a wall, a temple, etc. – but it is simply a way of helping the space to be transformed. In Noetic, there is a moment when the dancers lift up the rings into a dome shape. It looks like a cathedral, or an orb that they all must carry in order for it to float. If one person fails to carry it, another person gets crushed by it. This is how bodies are amplified by the objects, and how the architecture dances along with the bodies.

Judith: I saw this fragment of you dancing in Corpus Bach (2006) in which you express the movements of the cello music that was performed by Roel Dieltiens in front you on stage, as a beautiful echo. It wasn’t just about expressing the string instrument; you became the instrument yourself.

Finding commonality in movement, rhythms and shapes of the objects in relation to the body can also be applied to your work as a researcher, and how you acquaint yourself with different dance styles or cultures. In Play (2010), for instance, which you performed together with Shantala Shivalingappa, the idea of becoming the other seems to be a way of wanting to inhabit something or someone. How do you explore this cross-pollination of exchange and quest for habitus within your own body, but also within the work that you

make?

Larbi: The fact that you mention Play is very exciting, because Play was literally about remembering that being on stage is a game. We are playing a character. Even if it is informed by real events, it is a form of re-enactment, and a way to digest difficult moments in our lives. The notion of play is especially important to me. We live in a time where many things try to divide us. As much as it is extremely important to be mindful of each other’s boundaries, we should also keep challenging each other, and continue to connect because isolating from one another is not going to make humanity move forward. That can only happen through connection. Sadly, in history there have been many moments where the connection has been forced, and things have been taken out of context, out of their nature. Cultures have been absorbed in an aggressive way. As much as we must be mindful of cultural appropriation, we also have to keep working on cultural exchange.

That is why I based my latest work Vlaemsch (chez moi) (2022) on my own culture, since I am living and breathing a million things in this body that are from elsewhere. I grew up with so many cultural influences that make the body I have out of touch with the culture I am supposed to be from, and the culture I feel connected to is not mine to claim, according to some people. Vlaemsch (chez moi) became a wink to forty years of growing up with that contradiction.

Judith: I wonder, how do you find and nurture kinship in that space of contrasts? I suppose exploration and research can equally be applied to partnerships in dance, like the one you share with Akram Khan for instance, which can offer a certain softening into each other’s bodies and minds. How has this collaboration informed your practice over the years?

Larbi: As makers, as human beings, we look for like-minded individuals, you look for your community. When I saw Akram perform in 2000, I was so happy to see so many details, especially detailed finger movements in choreography. I didn’t know anything about the Indian classical dance Kathak, which involves extensive and detailed hand movements and footwork. I just knew I understood the language physically. Akram and I did a workshop in 2003 to eventually create a piece in 2005 called zero degrees. It was a moment in both of our lives of reconnecting to our bodies. That is why the dummies representing our respective bodies, created by Antony Gormley, are on stage. As choreographers, we are seen as people who organise other dancers. Akram and I crossed paths at an interesting moment, because we wanted to stay connected and be challenged by each other. In all the reviews we were pitted against each other, black against white. People want to create oppositions everywhere, even though there are so many clear similarities between us. Akram was raised in London by Bengali parents. Inside that family structure he was allowed to dance, which was quite different from my upbringing. That’s what we wanted to talk about – that we have similar roots that were interpreted very differently in our lives.

Judith: This concept of shared differences is ubiquitous in Babel (words) (2010) as well, in which you employ language quite heavily. Not as a tool for clarification, but as an instrument to evoke confusion, and to find empathy in that confusion, as another way of creating kinship.

Larbi: I love using language to show how little we know. Because the danger lies in thinking you know it all, there is nowhere to go after that. Babel shows to what degree every culture thinks it is the most developed, the most poetic, the most intricate or the most elegant. The premise of the story of Babel is that God punished us for our pride for thinking we could be as powerful as him. So, the story goes that he separated us through different languages. But then these languages are gorgeous; they are very beautiful. Diversity offers an eternity of exploration. Babel is a little bit of both these ideas: language speaks to our collective confusion, and our collective inability to understand each other fully, but if we start from that premise we might understand more than what we hoped for. When you called me a researcher earlier, I think it’s true, because it is also what I want the audience to become. In Babel, we also wanted to underscore the quality of dialects and to emphasise the diversity within languages. In my work, I tend to excavate things that will potentially go forgotten.

Judith: I find it so interesting, because the idea of listening to what you don’t understand is such an intimate experience. The way we use our mouths, tongue and brain, the way this informs our bodies is so different yet similar for everyone. Language is a shared struggle that way. As a composer of music, do you approach music from a similar perspective, as a tool for translation or creating closeness?

Larbi: There is definitely a magical element to music. Chords are like relationships – the way they bind to each other and create a vibration that moves parts of you and can trigger feelings of discomfort, relaxation or melancholy. Music is one of those secret languages.

Vlaemsch (chez moi), 2022. Courtesy of Eastman. Photo: Filip Van Roe

Judith: When thinking of your process, you seem to feel very comfortable within the unfamiliar, as being the entity that walks into a space that is unfamiliar to others, and you are unfamiliar to whatever the environment is. How and where do you feel at home?

Larbi: I grew up with a lot of restrictions and contradictions, and with a lot of spaces in which I was not allowed to do or be certain things. I had to hold my tongue. Some spaces required a specific religious approach, others prohibited that explicitly. It was very strange for me as a kid; I felt my voice was trapped but it helped me to understand the limits of reality. Contemporary dance offered a space for release. Everything about myself was brought together, welcomed and understood, including my obsessions with mathematics, language and social structures, as well as my critical thinking. However, contemporary dance is complicated. It embraces everyone in the beginning. It looks for the new, and it is very forgetful. It is important to acknowledge the lineage we are part of, and so I try to free myself inside this space. Theatrical dance is my source, but I work in other fields as well, even though I do not feel I can trust any of them to harbour me. With everything I have gathered over the years, I would like to make a work that integrates the separate elements that I have studied, that I have incorporated into my system, and now wish to realign. I feel most at home when I am a vehicle for information that I think is valuable, when I denote the norms.