fig 1:

Sugar

A gander through the candy store, or a swoop through the confectionary aisle doesn’t lie: sugar takes manifold forms. From powdered sherbet to sticky toffee, airy meringue to crunchy brittle, creamy ice-cream to gooey gums, from soggy dough to delicate candy floss, the number of textures and applications surely qualifies sugar for the title of most plastic food substance. Sugar’s plasticity doesn’t end at food: it is an excellent preservative, medicine, decoration, exfoliant, epilator, placebo, explosive, 3D-printing substrate and special effects glass. As a word, it is just as plastic. It evokes so much sweetness, which gives us not only semantic but biological oral pleasure, that adding ‘sugar’ to just about any word gives it an erotic, endearing or narcotic meaning. So the sugar bells might ring the sugar shaker while the sugar musket ploughs the sugar muffin, but the sugar pearl is the true route to sugar blasting. Or perhaps you’re sugar backing after you sugar flipped, which is known to make one sugar wild. Know what I’m saying? No? Sugar! A euphemistic exclamation for shit. Sugar is polite, and its role in sweetening the coffee houses that sprang up in the 17th century was crucial in the development of so-called polite public society run on the code of our sweet manners. The persuasiveness of sweetness has been recognised since before Christ – sweet’s Indo-European root word Swadish means both sweet and persuade. A more obvious synonym of sweetened persuasion, the word sugar-coat dates back to the early 20th century when sugar began to be used to create a protective layer for pills.

John Frusciante after recording Blood Sugar Sex Magik. Recorded with super producer Rick Rubin in the now-famous surrounds of The Mansion, Blood Sugar Sex Magik saw the Red Hot Chilli Peppers at their absolute peak, fusing the hardcore energy of their funk-punk roots with the soulful energy of a young John Frusciante, who infamously left the band while touring the record and spiraled into a six year stint of heroin addiction.

fig 2:

Blood sugar

Sugars get a whole lot more plastic as the chemical class of molecules that are carbohydrates made of carbon, oxygen and hydrogen. They take the form of monosaccharides, such as glucose and fructose; ribose and deoxyribose, the backbone of DNA; disaccharides, like saccharine, white table sugar comprising a glucose and fructose molecule joined together and lactose, the sugar found in milk; as polysaccharides, long chains of monosaccharides or starch. Although this class only makes up 1% of the human body, sugars animate us. Sugar is energy. Whether something metabolises glucose is the crudest definition of a carbon-based lifeform. If we didn’t eat glucose, the body would make it, because without glucose there are no thoughts fired in your brain enabling the reading of this sentence or muscle contractions to keep up your heavy panting. We need sugar to think, we need sugar to fuck. If we metabolise about 100 calories in twenty minutes of sex, as some research suggests, and there are 387 calories in 100 grams of sugar, we need

about twenty-five grams or five teaspoons a fuck. A healthy blood sugar level is about one teaspoon of sugar pulsing through our veins at a time, with the reserve held in the liver until needed and a second reserve in the system that turns our fat layers into glucose.

In the bestselling 2012 book The Blood Sugar Solution, Dr. Mark Hyman discusses the affects of sugar consumption on a functioning libido, among other detailed outlines on how best to combat the pull of sugar.

fig 3:

Sugar rush

Within thirty minutes of consuming pure sucrose or glucose on an empty stomach, blood sugar levels peak. Over the next fifteen to sixty minutes they slowly fall back to resting point. Various factors can play havoc with these levels, including adrenaline and endorphins, which is why, for example, BDSM guides encourage doms to give subs fruit juice or soda – not chocolate because it takes too long to digest – during aftercare. Although many of us will attest to the notion of a sugar high, scientists are now claiming that we imagine it – sugar is after all the archetypal placebo. Sugar science is becoming more and more disputed and difficult to discern as Big Food goes up against diabetes campaigners in an information war that has been described as dirtier than the tobacco industry versus the cancer campaigners. Regardless of the qualitative affects of sugar highs, evolutionary scientists pretty much agree that the Homo sapiens brain relies on glucose for functioning, and a key evolutionary stage was eating carbohydrate-rich foods some 12,000 years ago. Over the past 500 years, the so-called carbohydrate revolution has intensified with sugar consumption going from almost zero to two teaspoons per day in 1820, with current rates at over twenty-five teaspoons making the life expectancy of a wage-slave go down. The sugar rush might not be biological, but like the gold rush, it’s certainly economic, social and cultural accelerating in (possibly spurious) correlation with increased sugar consumption. Some argue that without sugar we would not have had the brainpower for the Industrial Revolution or the Enlightenment. Although the brain is only about 2% of the human body, it takes about 20% of the energy consumed, and most readers will agree that it is by far the most power-ful sexual organ. The thing is, too much of a good thing flatlines or becomes harmful. Elevated blood sugar levels messes with insulin, leptin, testosterone, growth and dopamine hormones and, in particular, the orexin aka not-in-the-mood neurotransmitter that results in soft dick, dry pussy and low libido. This is according to ‘functional medicine doctor’ Mark Hyman.

Anna Planeta’s ship is full of granulated sugar – the very alchemical substance of sweet dream of communism for people made desperate by their poorness and powerlessness, and of the blind desire for consumption (stimulated by inequality and injustice) on part of the poor in the West, who unconsciously take mass culture as successful communism.

fig 4:

Sweet movie (1974)

A less functional Doctor Middlefinger is the physician inspecting the hymens of the contestants in the chastity-belt-sponsored beauty pageant with which the widely banned Sweet Movie begins. In the cinematic era of sexploitation, Yugoslav Black Wave cinema auteur Dušan Makavejev turned the skin flick into one of the most depraved, depressing, incisive and controversial political critiques of capitalism and communism. The movie follows two narrative strands: one of capitalism in which a virgin is kidnapped by one male stereotype after another until she ends up in a Parisian commune that indulges in vomiting and shitting on each other; and one of communism that features a Karl Marx-faced candy-laden barge that endlessly circles Amsterdam canals for its seductress captain to pick up rebels who are exu-berantly fucked and tenderly slaughtered in a bed of sugar. These visual affronts, and in particular, the scene in which the barge’s captain strips to an audience of children, ensured that the film would be banned in many countries. Makavejev’s use of visceral images to shock us out of our pre-programmed reactions was inspired by psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich. The pervasive sugar in all its plasticity symbolises political manipulation and numbingly sweet ideology. As bleak as the film is, Makavejev seems to think there is hope for us to wake up: the corpses wrapped in sugar come back to life in the final sequence. ‘Is there life on the Earth? Is there life after birth?’, a musical refrain repeats.

Food designers Bompas & Parr first came to prominence through their expertise in jelly-making, but the business rapidly grew into a fully fledged creative studio offering food and drink design and immersive experiences. After years of receiving enquiries about whether the pair catered for sploshing parties they, decided to dive into this mysterious world, exploring it in collaboration with fashion photographer Jo Duck and director Nathan Ceddia through their photo series and short titled Cake Holes.

fig 5:

Sploshing

One of the few scenes in which Sweet Movie’s virgin is happy sees her drenched in chocolate sauce for an advert. The Wet and Messy Fetish – better known by the catchy onomatopoeia ‘splosh’ – entails being aroused by being slathered in a moist non-bodily fluid, possibly slime or shaving cream and most likely food like cream pie, chocolate sauce, treacle, ice-cream, custard, batter and other sweet sticky matters. Two factors are at play in the arousal – the overwhelming sensory experience influenced by the temperature and tactility of the substance, and the psychological taboo of playing with your food, in any way you like. Some argue that cake-sitting, in which people sit on cakes, is its own fetish distinct from sploshing since it combines the Wet and Messy Fetish with the crush fetish, whose fiends are aroused by crushing food or something else with the body. Crushing adds more sensory dimensions to sploshing, explains dominatrix Mistress Shae Flanigan: ‘The surprisingly satisfying sound of a bum squashing a meringue is one sound I never thought I would come across, nor will I ever forget.’ When British food designers Bompas & Parr started, they were asked if they catered for sploshing parties. Inspired by this unusual request, they produced the Cake Holes film and photo series in 2006, and since the duo are certified jelly fiends, threw in some quivering gelatine pillows for the expectant tushies.

Shuga Cain is the stage name of Jesus Martinez, a drag queen, performer, baker and one of the season eleven contestants of RuPaul’s Drag Race.

fig 6:

Some Like It Hot (1959)

‘That’s just like Jell-O on springs,’ says Jack Lemon to Tony Curtis about Marilyn Monroe’s derrière in Some Like It Hot. With the camera perspective following their eye line, it was a risqué shot for 1959 when the Hay Code prescribed all manner of restrictions on the way sex can be represented in cinema. Running circles around the Hay Code’s ambiguities and contradictions by using a pun-laden script and the slapstick gimmick of Lemon and Curtis impersonating women, is the transcendental genius of what is still acclaimed as one of the best comedies of all time. See, it was okay for a ‘woman’ to look at a woman’s ass, cleavage and thighs with the audacious male gaze shot that has since become a standard in film. The other aspect of its genius was more incidental, in that it isn’t just any woman being ogled – it certainly isn’t Mitzi Gaynor for whom the role had originally been intended. It is the woman who inspired the term ‘sex symbol.’ It is Monroe playing Sugar Kane Kowalczyk, a name that speaks worlds about the layers of innocence, sweetness, objectification and consumption embedded in the then sex symbol. A laconic but high-spirited, promiscuous and drunken ukulele player, Sugar Kane is quite frank about being on the hunt for a sugar daddy after being left ‘sucking the fuzzy end of the lollipop’ too many times when losing her heart to saxophonists. She’s not the type of character typically rewarded with true love by even today’s Hollywood narratives, but Monroe plays the role with her trademark ditzy-but-suave-and-unabashed-swagger that both transfixes and mocks the male gaze, winning all of our hearts. Monroe won a Golden Globe for Best Actress for the role, but she was already on a downward spiral – it reportedly took forty-seven takes to deliver the line ‘It’s me, Sugar.’ But as the fiancé of Lemon’s Daphne character replies when she reveals that she is a he, ‘Nobody’s perfect’ – the glorious heart of the movie. Reading into the film based on Monroe’s personal life gives it its timeless comedic staying power. Its legacy continues in contemporary explorations of gender such as Ru Paul’s Drag Race. ‘I’m the Latina Marilyn Monroe! I got more legs than a bucket of chicken!’ declared season eleven participant Shuga Cain on Instagram.

Sponsored Divas

fig 7:

Sugar dating

As Sugar Kane knew all too well, money sweetens the lollipop when it comes to snuggling up to rich oldies and uglies. These days Google is the all-purpose starter pack for sugar babe and daddy matchmaking websites, neighbourhoods with the highest density of sugar daddies (Chicago’s North Side in the US, the Entertainment District in Toronto in Canada), helpful tips on setting an allowance and detecting scams and feel-good stories about ladies paying their university fees (40% of sugar babes are students). Painfully misogynistic, new terms like ‘sugar mamma’ and ‘sugar bitch’ point to some economic redistribution since the coining of ‘sugar daddy’ in the early 20th century, but it feels like lip service. The News tab on Google is also where the not-so-feel-good stories of abduction, blackmail and abuse lurk. Yet, just when it didn’t seem like anything could redeem sugar dating, a press release from the world’s largest Sugar Daddy dating site, SeekingArrangement, announces that CEO Brandon Wade has ‘permanently banned President Donald Trump from his dating site, stating the Sugar Dating community doesn’t acknowledge him as a real Sugar Daddy.’ What a Happy-Birthday-Mr-President, and not even a single outraged tweet from Cheddar Boy (insert single-tear-emoji). With over twenty million members worldwide, the SeekingArrangement homepage promises four sugar babies per sugar daddy, ‘ideal relationships’ defined as ‘upfront and honest arrangements with someone who will cater to your needs,’ mentorship by ‘established Sugar Daddies [who] offer valuable guidance for longterm stability,’ that their ‘average member finds their ideal arrangement in 5 days,’ and a free upgrade for US students who sign up with their .edu emails. Well, at least it’s a refuge from Alpha Molester!

fig 8:

Sugar rimming

‘Press the moistened outside rim into the plate of sugar. Gently shake off any excess. Let harden at room temperature…,’ in fact not describing analingus (or sugar bowl pie, for your next water cooler conversation) these are instructions from Punchdrink.com on how to sugar a cocktail glass. Sugar rimming was pioneered by Joseph Santini in the mid-19th century in New Orleans with his Brandy Crusta, which sounds like the sugar daddy of cocktails: ‘a rich, fussy and obscure cocktail that, frankly, few of us have ever heard of – let alone actually tried.’ With a cognac base seasoned with lemon juice, Curaçao and maraschino liqueur, the Brandy Crusta was not only the first sugar-rimmed cocktail, but also insisted on an entirely lemon-zest lined inner rim. This elaborate garnish explains its obscurity and legacy as the sugar rimmed glass. The first recorded history of a cocktail as a ‘stimulating liquor composed of any kind of sugar, water and bitters’ dates back to 1806, which cocktail historians agree seems rather late. Nonetheless cocktails only became popular in Prohibition-era America when it was necessary to creatively mask the dubious quality of the homebrews.

Most commonly referring to heroin or a beautiful black woman, the term ‘brown sugar’ has also come to be known as marijuana. This is partially thanks to D’Angelo’s 1995

neo-soul classic ‘Brown Sugar’, which chronicles his love affair with the ‘pretty gritty Bitty’.

fig 9:

Seersucker

Another theory is that the sugar daddy of cocktails went out of fashion at exactly the time as Prohibition, far too fancy for bootleggers and rumrunners. In the 1930s, the seersucker fabric worn by blue collar workers was taken up by Ivy League students who ironically sought to identify with the proletariat – sound like a certain contemporary generation into reviving long-lost cocktails, twirling their face fur, and well, love or hate it, being sartorial influencers? Between the reviving ways of the hipster, The Great Gatsby movie and Mad Men, this year’s gladdest rag on the catwalk is the seersucker – most strikingly in Thom Browne’s coquettish Marie Antoinette-, football- and ballet- inspired range of genderbending tutus, ball bags, birdcage hoop skirts and corsets, and oversized jockstraps. Originally a silk worn in colonial India by workers, the material was reinvented in the US in the early 20th century in cotton and rayon. The gathered threads give it a bumpy consistency that makes it lightweight, easy-to-dry and ironing-free, a rough and smooth texture alluded to in its name – from the Hindi srsakar meaning milk (sr) and dark gravelly sugar (arkr).

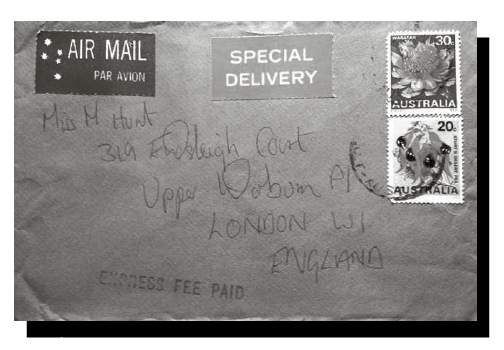

On 12th December 2012, Sotheby’s London offered a remarkable series of passionate and articulate love letters written by Mick Jagger to his lover, the beautiful black American singer (and inspiration for ‘Brown Sugar’) Marsha Hunt, during the summer of 1969. The letters were written while Jagger, the frontman of the world’s most successful rock band, was in Australia filming the movie Ned Kelly. At the time, their relationship was a closely guarded secret: Jagger was at the height of his creative powers and the symbol of rebellious youth, Hunt was the image of ‘Black is Beautiful’ and the face of the landmark West End production of Hair. Beguilingly lyrical and displaying a wide range of cultural interests, Jagger’s letters, written at a time of great personal and professional turmoil, shed new light on the rock legend.

fig 10:

Brown sugar

Since 1971, according to the Routledge Dictionary of Modern American Slang and Unconventional English, brown sugar means heroin or a beautiful black woman. Even though the Rolling Stones’ eponymous hit single was released that year, ‘a funky, swampy, rocking celebration of the rape of enslaved Black women,’ as critic Emily L. Hauser writes, the definition comes late. Perhaps this was just the first written usage – although the song was written and recorded a year and a half earlier, and drew heavily on the slang of the Deep South. Legend has it that Mick Jagger penned the inflammatory lyrics in forty-five minutes based on letters to his lover and first baby mamma Marsha Hunt. Iconic lead of the musical Hair (1967), Hunt auctioned off the letters for £187,250 in 2012. As the septuagenarian rockers initiate their umpteenth tour, op-eds by Hauser and others revive the decades-old debate about whether the song should be retired – although it is unclear about why just the song should retire. ‘God knows what I’m on about on that song. It’s such a mishmash. All the nasty subjects in one go… I never would write that song now,’ snake-lips himself said. Ardent fans attempt to defend the song as being about heroin. D’Angelo’s 1995 genre-defining neo-soul classic ‘Brown Sugar’ unabashedly refers to marijuana. ‘We be making love constantly / That’s why my eyes are a shade blood burgundy,’ he croons in a sultry voice, inspiring the first (written) use of ‘brown sugar’ to refer to a sexy black man. In 2002 the romcom Brown Sugar ‘destroyed the taboo of black love in cinema,’ according to a 2017 article by Amirah Mercer in Vice. Directed by Rick Famuyiwa, the film is a pioneer in what is only starting to become a given – African-American characters represented with depth and complexity, in a non-objectifying sexual relation-ship. Words and movies not only have different meanings in different contexts and times, but an etymology based on first release is automatically filtered by the past’s moral judgements. How will the metonymic values of sugar and sweetness shift as our relationship to these things change, and how will we look back differently at consumption culture?