Two guys make eye contact. They barely speak before pressing their bodies together. Maybe they’re sitting in a parked car at a cruising site in Memphis. Perhaps they’re dancing in an East Village bar. Or, maybe they’re lying in bed together in a home they’ve shared for twenty years. In the films of Ira Sachs, each scenario offers the possibility and risk of intimacy. His unofficial trilogy, which includes ‘The Delta’ (1996), ‘Keep the Lights On’ (2012), and ‘Love Is Strange’ (2014), maps love and desire over a lifetime, from teenage hookups and anonymous sex to coupledom and late marriage. Highly autobiographical, they chart the director’s personal evolution, both as a filmmaker and as a gay man who came of age in the 1980s. They show us how people come together and fall apart, and what it means for two people to get closer.

Paul: What’s the first erotic imagery that you came across?

Ira: Well, erotic imagery isn’t something only generated by culture. It can be the people you see. One thing that was interesting for me was that my sexuality was constructed around people who were not my own age, and not from my background. In my twenties, I found out that my two closest teenage friends were actually having an affair with each other. I was actually in the same spaces at times when they were getting it on, completely unaware.

Paul: I wish I’d gone to your high school.

Ira: Laughs] When you’re young, you think everything’s so private, but the experiences are actually so common. Teenagers in particular share so little about what’s going on, and that is kind of tragic. Just in the next room, the same thing is going on. At that age, you have no consciousness that there is a next room. I see that with my kids now. They have no idea that there’s another family living next door to us. I mean, I don’t really know, and I’m 48.

Paul: Were you aware in high school of other kids being gay?

Ira: I came out in my senior year of high school in 1982. I was sixteen and aware that there were other people who signified as gay, but I didn’t actually think about other teenage boys having sex with men. I was very aware of my own desire, in a strong, palpable way.

Paul: The cruising site in the The Delta was based on a real one in Memphis. Did it function as a kind of safe space for a lot of different groups?

Ira: Yeah, definitely. It felt so much more protected than the rest of the world. Your desire could be open, so that was extremely comforting – even compared with non-sexual spaces where one was more concerned that your sexuality would be revealed.

Paul: I was recently reading Michael Warner’s The Trouble With Normal and thinking about the politics of shame around sex in America. A few weeks ago, I accompanied a friend to a sex party organized in an underground space in Brooklyn. At about 2 am there was an exodus, and suddenly, all these men in their underwear were putting their clothes back on. It was a strange moment – all of us dressing in silence under bright lights, after this communal experience in the dark. I thought of the different worlds these men were returning to, and all the people they’d never tell.

Ira: Right. People don’t leave spaces like that and go tell the first people that they run into. There’s a lot of pleasure in the illicitness, and in the community that’s formed there.

Paul: I guess I’m connecting it to The Delta. The first scene at the cruising site has no dialogue and lasts for about 10 minutes. The men communicate with their bodies. What’s interesting is that when Minh get into Lincoln’s car, and Lincoln goes down on him, the camera stays on Minh’s face. ‘The erotic’ is often about suggestion. It’s about what’s just outside the frame.

Ira: As a filmmaker, a lot of what you’re trying to do both narratively and visually is to create questions for your audience – and mystery. I always think there should be a big question mark over a scene so that the audience wants to know more. It means [the viewer is] hungering for attachment to those images. Specifically, I try to think of each scene as a middle, not a beginning or an end, and to sequence films as a series of middles.

Paul: There’s a connection between cinema and cruising, which is the erotics of looking. It’s what charges any space.

Ira: A bar. An airport. A museum. As a filmmaker, you’re trying to be comfortable with sexuality without making explicit images. By explicit, I mean graphic. I don’t make graphic films, so how do you depict intimacy and sex? You have to do that through the figurative – it has to be a metaphor, in some way.

Paul: Has your relationship to depicting sex onscreen changed, since the mid 1990s?

Ira: It’s never been my greatest strength. That’s why I watch a lot of great European cinema, when I’m trying to figure out how to shoot sex.

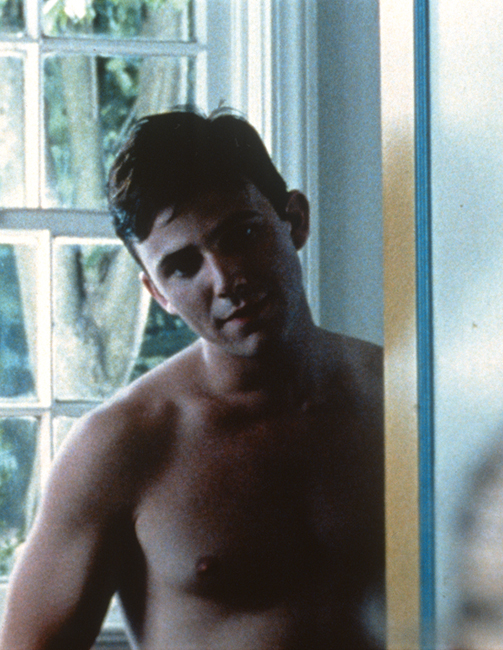

Shane Gray in The Delta. Courtesy: CG Productions

Paul: You hesitate to show it?

Ira: Yeah. You have to cast people that you can imagine being intimate with, not necessarily physically – people that you feel are knowable and permeable as human beings. With Keep the Lights On, I benefited from the fact that neither one of my actors shared that inhibition. I’d say you’re only as good as your actors, and Zachary Booth and Thure Lindhardt were both extremely comfortable with their bodies, which helped a lot. They carried the film to a place that, while not necessarily graphic, certainly was not prudish. The first or second day of shooting was actually their first sex scene. I’d been given advice from Antonio Campos, who’d just done a film with graphic sex. He said to do the sex scene early in the shoot. That was very good advice. You’ve got to get it over with. Actors are able to take these leaps because they can imagine the person in front of them is someone else, partially. They project and fantasize. They give in in a way that I never could.

Paul: Are your films more interested in behavior than psychology?

Ira: No, I don’t think so. You can’t separate the two. My films are not trying to explain psychology, but they’re trying to be psychologically accurate in terms of relationships. I think the job of the filmmaker is to be attentive to psychology, anthropology, sociology, and to have a Marxist understanding of class, and the place of money. In classic Broadway musicals, there’s typically a musical number that happens at ten o’clock during an evening performance. It’s the moment when the character belts and also reveals him or herself in a really deep way. Rose’s turn in Gypsy, for an example. I’ve realized that films also tend to be structured around a ‘ten o’clock number.’ That’s when the exterior drops and the interior is revealed, which is an interesting moment because in a way, it’s when the outsider becomes you. It’s something that a filmmaker can manipulate, and something I’m much more conscious of doing now. It comes from internalizing narrative structure. I’m thinking of the reveal, which is when the person becomes ‘visible.’

People imagine anonymous sex to not be intimate, but that’s not true. It’s a particular form of intimacy, and for many of us, it’s very real. You go right to the core of somebody.

Paul: The Delta and Keep the Lights On are about how people have very different personas that they perform, consciously and unconsciously.

Ira: Yes. I think gay people have a particular disunity that was forced upon us by the closet. Happily, thirty years later, it’s less true. I’m more unified than I used to be, and that process is where Love Is Strange comes from. It comes from a different potential to create intimacy in my own life. All my films were stories of deceit, a subject that I found extremely compelling. But I just don’t find it compelling anymore, personally.

Paul: I know you’re a great admirer of Maurice Pialat. His films are often autobiographical and tend to focus intensely on the dynamics of intimacy.

Ira: When I was in college, Harold Bloom wrote a well-known book called The Anxiety of Influence. Certainly, it’s something I experienced with Pialat, whom I can never come close to, but with whom I’m always in close conversation. I continue to learn new things from him. Love Is Strange has the most Pialat of all my films because I’m using the camera in a way to become more emotionally direct. It took me a long time to realize that was something Pialat was doing.

Another big influence is Ken Loach, whose filmmaking comes from a photojournalism background, meaning using a long lens and being farther away from the subject. It’s more about characters in space, rather than characters with the camera.

Paul: There’s something of a paradox with the long lens, in terms of achieving intimacy through distance.

Ira: For a long time, it was the only position I was comfortable with.

Paul: What films influenced how you shoot sex?

Ira: I was very influenced by L’homme blesse (1983) by Patrice Chéreau, which is a wonderful film that’s not only about sex, but about compulsion, as is a great Jules Dassin film called Night and the City (1950). It’s one of the most compulsive movies I’ve ever seen. A film called A Bigger Splash (1973) with David Hockney was also a big influence. It’s a documentary, but it’s constructed like a fiction film, and as such, the sex is really sex.

Cinematically, compulsion is an easier thing to display than sex. Erik in Keep the Lights On is deeply compulsive. From the first minute of the film until the last, he’s always searching for something. He has a bottomless need, and that search is what drives the narrative, which I relate to.

Paul: Your films seem to represent the analog world. Guys pick up one another in person in bars and cruising sites or calling a phone sex line. Today, it seems like digital space is supplanting physical space – apps instead of bars.

Ira: In the 1990s, phone sex was a common mode of interaction. I’m less judgmental in film than I am in life. I try to be understanding of all the different ways people try to connect with one another. People imagine anonymous sex to not be intimate, but that’s not true. It’s a particular form of intimacy, and for many of us, it’s very real. You go right to the core of somebody. And what’s more theatrical than being on a phone sex line? It’s a performance that ties to something very real, which is desire and fantasy. Even if something’s a fantasy doesn’t mean it’s not real. It’s real in your personal erotics.

Paul: That’s an incredibly important point, which is that intimacy can be experienced in a lot of different ways. You can have an intensely intimate exchange with a stranger, and it’s as valid as the intimacy you share with a friend or lover.

Ira: I agree. But for me, there was a cost to participating in a world I couldn’t share. There was a cost to leaving a sex club at 2 am and not telling my coworkers in the morning. There was a pleasure to it, but there was a cost. Keep the Lights On was trying to speak to that cost without being pejorative. It’s challenging, and I think some people felt that the film was too much pain and not enough pleasure, given all the pleasure that one has. But for me, it was depicting a certain crisis. All my films are about crisis, which is drama. The only thing I’m really interested in depicting is the nature of intimacy within a societal framework. The hardest thing to say anything about is not intimacy but sex. What film really tells you very much about sex?

…He has a bottomless need, and that search is what drives the narrative…

Paul: You didn’t see Nymphomaniac?

Ira: It wasn’t my thing. It’s very hard to talk about sex in a nuanced way in film. Books do it much, much better. Harold Brodkey, who was an extraordinary writer and who died too young, wrote a short story called Innocence. It’s thirty pages just describing sex, and he’s able to get the moment-to-moment of sex.

I’ve never seen a movie that’s been able to do that very well. You can talk about power relationships, bodies, erotics. But it’s very hard to talk psychologically about sex in cinema.

Paul: Is that because of the sheer power of the image?

Ira: It’s just actually hard to depict the psychological. With film, there need to be edits. It needs to have drama. Usually, they don’t have a dynamic that shifts within the scene. They don’t have the complexity that they have in life, right? Cinema works better in large dramatic passages than within the narrow confines of the sexual act. How much are you learning about sex in the opening scene in The Delta? That’s actually why Andy Warhol’s Blow Job is good, because you’re watching the sex in real time. That doesn’t happen in narrative cinema very much.

Paul: Earlier this year, I spoke to Alain Guiraudie, director of Stranger by the Lake.

Ira: I love that film. That’s a film that does a good job talking about sex.

Paul: It’s a film that addresses aging and explores the tension between sexual desire and companionship. The Delta, Keep the Lights On, and Love Is Strange, together show how desire and love evolve over a lifetime.

Ira: Some would say that Love Is Strange, which is a portrait of marriage, is not about sex but about love. Perhaps this speaks to the place sex occupies in a long-term relationship.

Paul: But physical intimacy remains important, even if it’s not sexual.

Ira: Yes, it’s about doing with one person what you don’t do with everyone else, which is that your bodies touch. People can know each other a long time but their bodies never touch. John Lithgow and Alfred Molina brought to the film their own histories as men who’ve been married for twenty-five or thirty years. For me, it’s very hard to be anything but a very personal filmmaker. I mean, it’s a big thing for me that I have no interest in telling stories about the illicit anymore. Having myself lived another way for so long, I can’t bear it. I’m interested in maturation as a point where you accept yourself. My films are different now, for that reason. To say that the films are a trilogy is also to say that they are my life.