Carlos Motta’s black-and-white photograph Untitled (América Latina) (2016) captures a nude male figure on his knees. He’s facing away from us and while he’s not quite on all fours (his hands, held almost in prayer in front of him suggest he’s hoisting himself up by his forearms), the perspective forces us to focus on his ass. Written across his butt cheeks are the words ‘AMERICA LATINA.’ Like much of Motta’s work, this portrait anchors the sexual in the political. A literal reading of the work – a metaphor image of the continent’s body ready to be fucked – requires one to examine just how much of political rhetoric comes to depend on sexualised bodies. But in making it flesh ‘Untitled (América Latina)’ also reminds you how the body (the queer body in particular) is always at the mercy of the body politic that constructs and marginalizes it.

To encounter Motta’s work – which ranges from radical queer manifestos and essay films on historical homoeroticism, to video installations on Christian theology and iconography, to sculpture exhibits of hermaphroditic figures – is to see art history being rewritten from the inside. Gaps in knowledge, in historical narratives and documentary records, do not represent, for Motta, a lack. Instead, they are sites of possibility. Spaces where marginalised bodies are both recovered and reimagined.

Stills from Nefandus, 2013 HD video/sound, 16:9, 13:04 min

Manuel Betancourt: I wanted to start our conversation by talking broadly about how central gender and sexuality are to your work. What animates you to delve deep into and expand on how we understand both of those concepts?

Carlos Motta: I became interested in the politics of gender and sexuality through a large investigation about political systems, and the way they are perceived and enacted in society. For the first several years of my work I focused specifically on the idea of democracy and how it has been implemented, particularly in Latin American societies. I produced a series of works that delved with into democracy as a political system and as a cultural construct. In the process of developing those works I started to find that there was an ever-present idea that there are ‘big issues’ and ‘small issues’. In the socialist Marxist tradition the big issues of social justice is class. There is a clear hierarchy of issues, and gender and sexuality are always at the bottom. When I was making The Good Life (2008), a project where I interviewed people on the streets of tweleve Latin American cities about their conception of democracy, there were a few people that spoke about their understanding of democracy in relationship to affects and emotions. I found that really interesting because until then I had never thought about these ‘small’ issues at the same level as the ‘large’. That is when I decided to turn the intent of my work towards understanding the ramifications of sex-uality and gender as political subjects.

…it has been a process of insisting that sexuality and gender need to be always considered intersectionally…

Manuel: Was that an easy pivot to make?

Carlos: Well, it has been a process of insisting that sexuality and gender need to be always considered intersectionally. Once I did that, it became apparent that there was so much to talk about and to understand: from the historical processes of constructing sexuality and gender as forms of otherness, to the articulation of these categories as marginal subjects, to thinking about the histories of political self-organisation and social movements. What I have been doing is trying to shift the terms and to provide processes of documentation, historical inquiry, revisiting histories and creating other narratives that emphasise the centrality of these topics in social, cultural, political and economic dialogues.

Gender Talents presents portraits of trans and intersex activists who thoughtfully perform gender as a personal, social, and political opportunity rather than as a social condemnation. Based on interviews conducted in Colombia, Guatemala, India and the United States the project seeks to expose the ways that international activists challenge the bio-cultural ‘foundations’ of society and question gender norms from the perspective of sexuality, class, race, ethnicity and disability. Gender Talents documents the ways in which society conditions and regulates bodies and how gender activists build politics of resistance and action. From traditional Joggapa communities in India, to sex workers in Colombia and Guatemala, to intersex activists in the United States, these individuals and communities fight for state recognition, the right to self-determine their identities, self-govern their bodies, access to work, health benefits and other pressing issues.

Manuel: Recentering those social and political ideas on the body, as your work does, seems obvious to those of us who’ve been schooled in how systems of power operate on marginal subjects, and I’m curious how that then affected your work on an elemental level.

Carlos: I came to these topics through a cycle of works that used methodologies from documentary practice and dealt with social politics in Latin America. In particular, the form of the interview (as one of the tools to construct public opinion) was something I found fruitful to present alternative narratives. Some of the first works that I did that dealt specifically with gender and sexuality used that form. We Who Feel Differently (2012), for example, is a large-scale online database of interviews that also has an installation component where I interviewed people who had been active in LGBTQI activism since the 1960s in four countries: Norway, the United States, Colombia and South Korea. In this case the idea was to tap into specialized knowledge that had been produced by these people and the histories they had to fight hard to redeem. The project suggests that we should think about equality differently and recover the notion of ‘difference’ as a productive category to achieve political goals. Difference could be articulated as a generative way to produce counter-knowledges and counter-politics, as opposed to ‘equality’ that in many ways has come to represent an idea of assimilation within contemporary LGBTQI politics.

Manuel: This idea of seeing difference as a productive category, one which pushes back against ideas of normalisation, strikes me, still, as rather radical even as it harkens back to older forms of queer liberation rhetoric. What did that do to your work?

Carlos: The process of dealing with all of those interviews opened up a wealth of topics for me. We Who Feel Differently was essential to, on the one hand, think of the category of difference as a radical category that is not only discursive but also practical: How can one create a series of political tools to think about social changes that do not conform to existing, normative cultural, social and legal structures? And on the other hand, to allow me to speculate about history and think about how queer subjects have been erased, misrepresented, and how perhaps there could be a different way of articulating their stories through the use of historical fiction, essay films, sculpture and installation work.

Manuel: That brings me to something I wanted to ask you about, which is the various forms your work takes. How does your switching from, say, a sculpture exhibit to a video installation, affect or inspire your process?

Carlos: I never really thought of myself as a medium-specific artist. Early on, when I studied at the School of Visual Arts, I took a class with New York-based artist and educator Penelope Umbrico. The class was titled ‘Practical Theory,’ and it taught us how to think about practical applications of theory; to think about art in conceptual terms. Penelope challenged the commonplace ideas students have about art when they first get to school. One of these was the idea of having a signature style or discipline. Instead, she encouraged us to think about the primacy of ideas and how to make them come to fruition in the world. Through my interaction with Penelope, I got rid of the idea of medium specificity and became a conceptual artist. I focused on creating thematic content arteries that I wanted to deal with. Today, this sounds much more structured than it actually was at the time but I think of it retrospectively this way. What I have been doing is constantly finding the right formal application for my ideas. Sometimes a work begs to be a film that is going to be projected in a space and demands people sit down and watch it. Other times my work is better off as an installation that relates to the space, etc.

Deseos/رغبات

Courtesy of Mor Charpentier Galerie, Paris; P.P.O.W Gallery, New York; Galeria Vermelho, Saô Paulo

Manuel: That seems key, thinking of form as both fitting and advancing the ideas you’re presenting. In thinking through a particular piece, I wanted to hear what it was about Foucauldian /رغبات (2015), for example, that begged to be a film, and a film that so clearly depends on giving voice to those who’ve been silenced.

Carlos: Deseos/رغبات is a film project I started to work on after making the Nefandus Trilogy (2013–2014), which is when I became increasingly interested in historical documents that articulated the lives of queer people in pre-modern times: pre-Hispanic histories and colonial narratives. In that work I dealt with historical constructs and the ways in which some lives have been made available in the present only because of their existeance in archives. One of the characters in Deseos/رغبات, Martina, emerges out of a legal document that is found in the Archivo Nacional in Bogotá, within the criminal cases, in a sodomy trial. Martina’s life is defined by the very strict and normative historicising drive of the Spanish Crown to keep very specific records of social and moral transgressions, sins and crimes. I thought it would be an interesting project to rescue Martina from the constraints of the archive, from the ways her body had been made into an example, and to use historical fiction to provide another perspective on her life. It was a difficult process because on the one hand I was pointing at the fact that she has been reduced by institutions to a case study and that she only made it into history because there was something different about her body. But on the other hand, I was at risk of doing the same from a contemporary queer lens. But I made a pact with her in a dream and she sanctioned my project to represent her.

Manuel: Wait, in a dream?

Carlos: Yes, really, in a dream, and she said it was fine. I then began to think about Martina as someone with agency who would be very self-conscious about the processes she underwent: being examined and scrutinised very heavily. Martina was accused of being a hermaphrodite because her clitoris was larger than ‘normal’ after her employer and female lover turned her in. I wanted to give her a fictional voice that would present her as aware about her life, but also let her be free and express how she felt about all these humiliating encounters with power. In the film, when she is being inspected by doctors and lawyers, her mind is elsewhere. The official story ends with the resolution of the legal case: Martina disappears from the archive when she is found not-guilty. Another interesting idea that arose from recovering figures from the archive was to give their lives a happy endings: let them be characters whose stories don’t end with the resolution of their legal cases, but who actually find a way to become someone else. Deseos/ رغبات came about because I met Maya Mikdashi, a Lebanese cultural anthropologist who was also invited by the French organisation Council to work on a collective inquiry in Beirut around the criminalisation of sodomy. Maya and I thought we could use this invitation as an opportunity to develop a fictional epistolary conversation between two characters who where separated by geography and culture, but who were related by personal experience. We went to Beirut to try to find a similar case to Martina’s, only to find that the Ottoman courts were not obsessed with documentation in the way the Spanish Crown was. There were no records of same sex relationships between women that we could find. Based on that we realised this didn’t mean these lives didn’t exist but only that they weren’t documented. That is who Maya drafted Nour’s story, a woman who fought hard against tradition to live next to her female lover.

Manuel: In that sense, the film is a kind of Foucauldian endeavour, a way of excavating from the archive the lives that only found themselves there because of the ways they were being policed. But if the impetus was to create an epistolary conversation, what then pushes you to make a film?

Carlos: We were really interested in the ways that these stories of oppression are not just articulated in documents, but are perpetuated in all regimes of representation. One of the things I was most interested in when it came to Deseos/رغبات was how religious iconography could symbolically illustrate its characters’ perils. Religious iconography has greatly contributed to society’s ideas around the body, about the role of women in society, about patriarchy, and about the repression of sexuality. We decided to approach the visualisation of the film by layering iconographic and other images with a voiceover narration.

Manuel: Religious iconography is ever-present in your work. And that’s a good excuse to talk about the pieces that make up Requiem (2016), which so forcefully engages with the image and concept of the crucifixion. What drives you to queer these Catholic images? In Requiem, for example, we see you reproducing a crucifixion scene within the context of rope/BDSM play.

Carlos: All of the works that I have produced are somewhat connected to one another, even if they don’t appear so immediately. This project is connected to Deus Pobre (2010), an earlier work I did about liberation theology in Latin America. When I finished that project I was surprised to realise I had completely ignored queer liberation theology in a huge oversight driven by ignorance. It never occurred to me that there would be a liberation theology that would be coming from a queer perspective. A month after I presented Deus Pobre someone sent me an article by Marcella Althaus-Reid, an Argentinean queer and feminist theologian who wrote an important book called Indecent Theology (2000), where she looks at theology through feminist and queer perspectives. I knew back then that I wanted to return to that topic but I wanted to do it exclusively through a queer lens. Around the same time that I started to read Marcella Althaus-Reid, I met Linn Tonstad, a queer theologian teaching at Yale University who engaged with me in a conversation about queer theology and understanding how you can think of Christianity and its legacies that way.

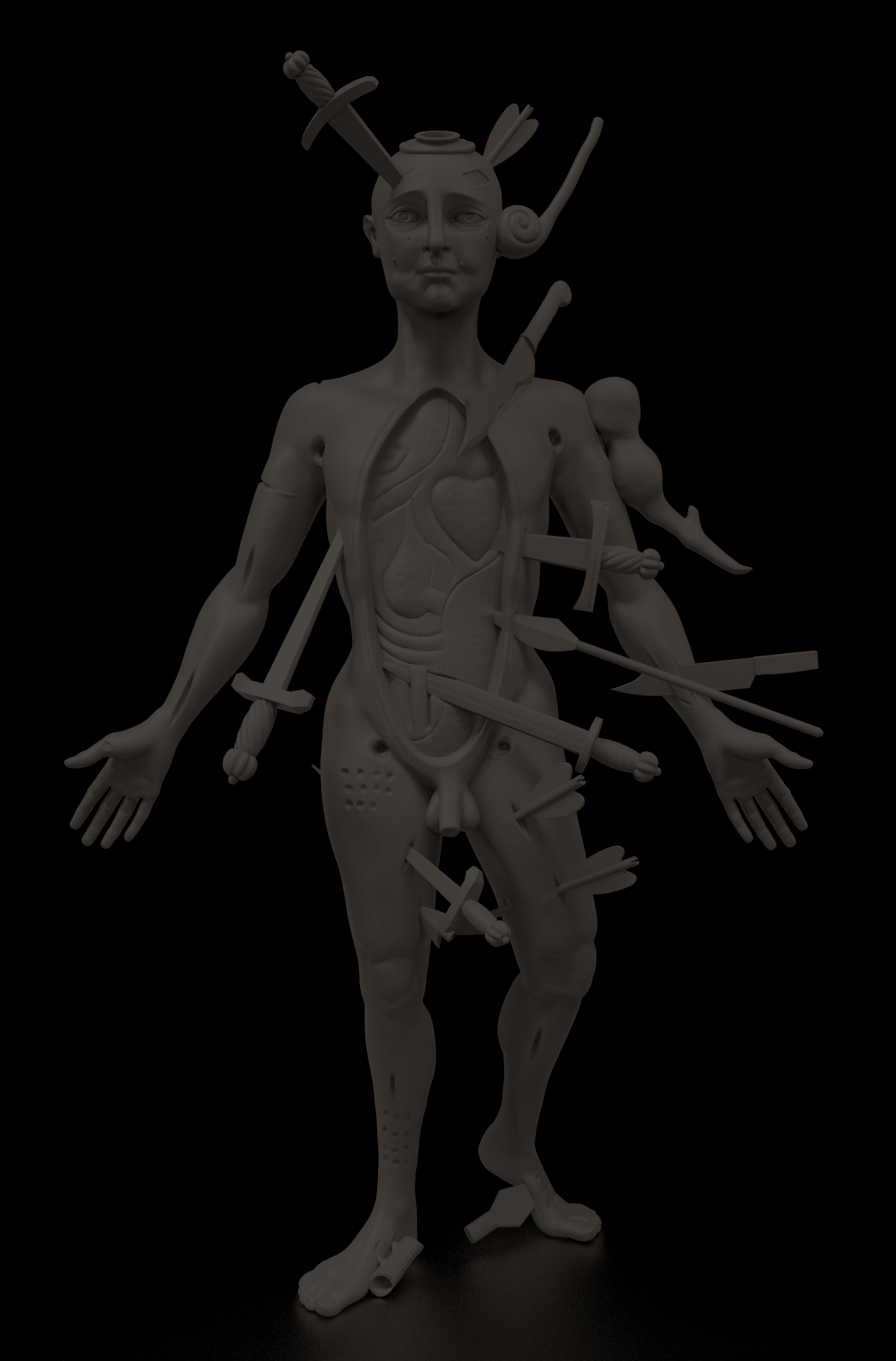

Beloved Martina, 2016, ten 3D prints

Manuel: Particularly because, as you point out, you need to be a critic and a believer at the same time. Your inquiry into these questions emerges in three distinct but complementary pieces which, in my mind, tackle the same idea from an aesthetic, an intellectual and a sexual perspective respectively.

Carlos: Yes. Requiem began in conversation with Linn. I asked her to give an exposé of the ways that she and Marcella understand the idea of the crucifixion as a kind of foundational myth of Christianity. I did an initial video with Linn, The End of Crucifixion, which is one of the three videos in Requiem, where she speaks about an inversion of the idea of the crucifixion. The crucifixion in the terms of Althaus-Reid, as they are elucidated by Linn, operates in tandem with the effects of capitalism on the marginal body. Somebody that is crucified is not somebody who is carrying the weight of their sins until eternity but is somebody who is constantly raped by capitalism’s social injustices. After that video I also wanted to do something that was a bit more visceral. I contacted Ernesto Tomasini, an Italian queer performance artist and invited him to work with me in a performance of Gabriel Faure’s song ‘Libera Me’ in his apotheosis Requiem (1887–1890), which is the part where man is asking for divine redemption. Ernesto performed this using a tenor voice but s/he is dressed as a kind of eccentiric drag queen, an angelic devil of sorts. Finally, I also wanted to speak about the kind of sexualisation and appropriation of religious iconography by queer cultures (fetish culture, bondage) as well the potential reading of religious violence as of a violation of the (homoerotic) body. I went on to re-enact Caravaggio’s Crucifixion of St Peter (1600). Saint Peter asked to be crucified upside down because he didn’t feel worthy of being crucified right-side up like Christ. I worked with two Italian bondage artists, Andrea Ropes and Stefano Laforgia, and re-enacted this painting for a live performance and a film, Inverted World (2016). They are dressed in leather gear and I am naked, being suspended upside down from the ceiling of a Franciscan chapel in Tuscany.

…They are dressed in leather gear and I am naked, being suspended upside down from the ceiling…

Manuel: What’s key, particularly, in that bondage scene is the primacy of the queer body. I don’t want to ask a glib question like, ‘Why is that important in your work?’ but I do want us to talk about the potentiality of the queer body in the art gallery, or in the museum space. I’m thinking here, in particular, of your recent sculptural works. Putting the queer body in a gallery is already creating a type of friction: what drives you to put it so squarely at the centre of your work?

Carlos: There have been three recent projects where I have been interested in the gaps in art history when it comes to the representation of queer bodies. One, which is perhaps the most significant body of work I did in the past five years, where I went over images that I had collected for a long time of pre-Hispanic sculptures that represented homoerotic encounters from different cultures, where you would find blowjobs, threesomes and other sexual relations between men. I was interested not only in these objects as objects or what they represented, but in the fact that there was virtually no documentation or argumentation about what these objects would have meant for those cultures. This led to many years of research on the ways in which the conquest was not only a process of imposing forms of governance, culture and religion, but also very specific ideas of sexuality and the body: how all of these things are epistemological impositions that went hand in hand with the actual destruction of a lot of these objects, let alone the traditions and the people that performed them. Through that destruction and erasure they made the possibility of thinking of these things and making them a part of history almost impossible. The absence of these objects from historical museums and institutional contexts led me to read academics who have dealt with these topics in an informed way, like Pete Sigal, and I started to understand that there was space for me to address this through contemporary art practice.

Self-Portrait with Death #4, 1996/2018. Courtesy of the artist and P.P.O.W, New York

Manuel: Right, so you tackle it from within the space of art history – museums, galleries. You even borrow their very forms. What does that accomplish?

Carlos: Well, the first piece that I made where I wanted to use a museum space to reintroduce these figures was Towards a Homoerotic Historiography. I made copies of the original sculptures based on the photographs that I had found and I worked with a goldsmith and a jeweller in Colombia to make casts of twenty of these pieces in silver, gold, and in tumbaga, and created a museum of miniature homoerotic sculptures. They are the size of your thumb; not because I didn’t want to make them big but because I wanted to make them almost invisible, to force people to go very close, literally to put their faces against the museum glass to encounter what they have never been allow to see.

Manuel: And, encouraging that gesture, do you focus on what you hope those who visit the exhibit will do once they walk out of the museum?

Carlos: You mean in their lives?

Manuel: Yes. There is something – I don’t want to say didactic, but there is an impetus in your work that demands or stirs something in those who experience it. Is the effect your work has on a spectator something you think about?

Carlos: This is a context-specific question because I hope a visitor in a museum who encounters any of my works will hopefully realise those absences in their own thinking, and think about what has been naturalised as forms of historiography or representation. This is why I want to be hyper-formal and hyper-careful about presentation.

This installation looks like a room you would find at the Gold Museum in Bogotá. This work has been recently acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, something that makes me very happy, as it will represent an intervention in an institutional discourse in art history. I want the experience for the public to be transformative, at least for a second, where somebody would realise, ‘Oh, maybe the way that I have been thinking about this is incomplete. There is a way for me to shift the lens and think of these issues differently.’