Since my arrival in Rotterdam I have been fascinated with the odd Chinese pagoda, which is crammed between roads just off the park at the foot of the Euromast. Strangely enough, this seems like a nice spot to speak with photographer Ari Versluis, whose work consistently centres on capturing the idiosyncrasies that make us human. As an avid traveller and someone who doesn’t shy away from immers-ing himself in different nightlife scenes, Ari Versluis has developed a broad scope of visual codes that transform into autonomous series, advertising campaigns as well as into work for the corporate world.

We relish in the soft sunny glow and talk about identity, confidence, attitude and the challenge of living your real self. As we settle in the grass Ari admires the quality of the site, and starts to describe this sensitivity in a beautiful picturesque fashion. He imagines a 1950s nuclear family, all pristinely dressed, coming to this odd scrap of grass, to take a picture with this phallic symbol of hope; the Euromast, amongst the patchwork of empty fields and building cranes. The travelling eye of the photographer reveals itself.

Nathalie Hartjes: This is really the post-war imagination for new beacons of hope. Much like the area around the Atomium in Brussels. But then again, it’s hard to imagine the site of the whole city in those days. I imagine it to be a patchwork of desolated places, empty fields and building cranes. So I guess at that time the Euromast stood out even more. Can you describe Rotterdam at the time of your arrival in the late 1970s?

Ari Versluis: During those years there was the early emergence of a punk scene that I still consider a vital cultural moment. Rotterdam was bursting with a strange energy at that time. It felt urban, overwhelming, and incredibly empty, dreamlike empty. This was atypical. All kinds of new initiatives were bubbling, like the founding of the influential magazine Hard Werken [Hard Work] and the underground TV programme Neon by Bob Visser for the VPRO network that became legendary.

Lots of small music venues were raging with new sounds. It wasn’t comparable to anything, not trying to copycat. I recently viewed a clip from a film by Dick Rijneke, Greetings from Rotterdam, where he follows the unprecedented punks de Rondo’s as they move through a completely desolate cityscape.

Everything was bare and the shock of the bombardment echoed throughout the city. A city with no heart. No future. Many historical venues that actually had survived the bombing had also been knocked down – as if the decision makers of Rotterdam were thinking, if we have to start anew, let’s not take half measures.

Nathalie: It seems like you have the ability to very casually morph between styles and scenes. Whenever I see you, you’re dressed in a different look. Is there connection with your work and have you ever been part of the scenes you depict?

Ari: Well, I enjoy moving through different scenes. I am more the voyeur than part of the scenes; this is a role that suits me well while it requires commitment and involvement to turn from the onlooker into an active agent. I was quite shy in my early years; in this respect photography has encouraged me to take on a more active, maybe even activist, stance. The punk and later the gabber scene had this DIY mentality and although we are led to believe that all is engineered top-down nowadays, this mentality is still crucial to any kind of innovation.

Nathalie: Could you tell me more about your appreciation for this DIY attitude –, does it drive the approach to your work in some way?

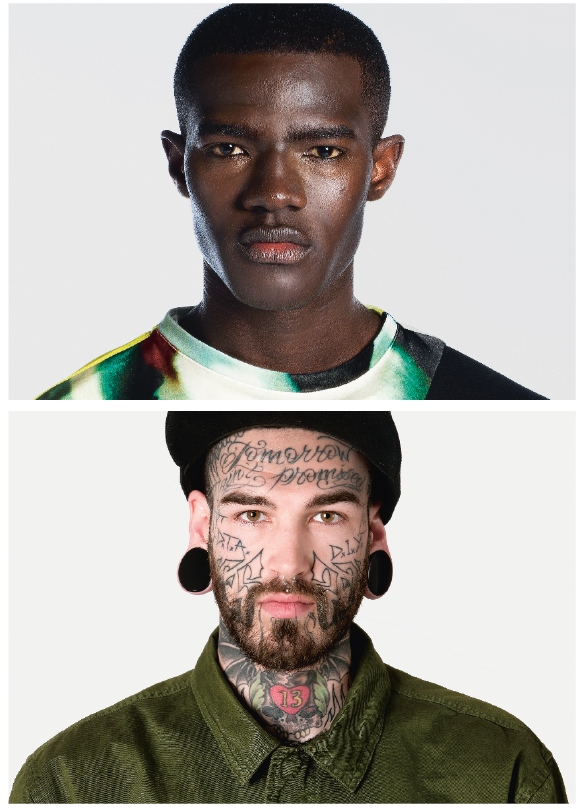

Ari: One of the main topics in my work is to portray fashion codes and outfits. For doing so, you have to be an expert viewer in the first place in order to depict the fashion codes that are combined within an outfit and become expressions of identity.

The starting point is to see someone, to recognize what has made your eyes wander. Something that is surprising or confusing, a conflict in outfit is sublime. When something clashes in a way that makes you think – What the fuck is going on here?! The next big step though is to approach people, which is a delicate thing to do, I don’t like startling people. This is why most of my work is studio work. Instead of slyly stealing a moment, I want people to approve of the way they are depicted and to create this moment when someone’s aware of what they are communicating with their outfit, how their emanates from their attire. Some people’s outfits actually make them fly! Clothes can be a way to defy so-called social status. People with no standing at all can look like they run the world – it really is about empowerment, about feeling the energy and engaging in role play.

The photos are a way of putting these people on a pedestal – to be honest, this pedestal is already created by themselves. The photographs are a form of profiling this self-image. My work takes this to another level. To make sure the image exceeds the staged document I strive for a quality so strong that it claims artistic status and therefore stands the test of time, that it becomes meaningful. This is something I realized very early on and I have been adamant in being precise in the technical decisions of the work, to choose consistently for a medium format camera and make sure I capture this intention of quality and awareness. On platforms such as Instagram, zooming out has been made impossible. So it is this particular technical quality of a wide image that sets the work apart from the extreme abundance of images we live in.

…our bodies are no longer straightjackets we have to adjust to. It’s the other way around…

Nathalie: As you are an expert viewer, I can imagine that you make notes of some sort. Would these be snapshots? We rarely see any lo-fi work of yours like this. Do they exist and how do they relate to your more publicized work?

Ari: Of course, first of all, there are tons of snapshots! Enough to raise levels of anxiety. It’s necessary to maintain an archive, to have the ability to sift through earlier material. The snapshots for instance are part of this context, as a measure or sketch of, literally, what’s up in the streets. And to a large extent the act of organizing, categorizing has always been central to the work. The archive is the living body of that act. So I need to keep revisiting it, refreshing my memory, but also at times to reinvigorate issues with topicality. It’s important to take the time to relive the archive, re-enact or re-embody its relevance for oneself to find out what might be applied again. Time and again I give a piece a new layer of appreciation by combining it with newly made photo work, or the archive allows me to rework a theme I had forgotten about.

Nathalie: It seems like this archive is a way to travel through time.

Ari: The whole body of work is about capturing something of cultural significance, and this is unmistakeably connected to time. The work is not merely about depicting individual faces or bodies. You have to study the encoded messages people carry with them, all these signs. In order to discover them, one sometimes just needs to sit still and watch.

Nathalie: So by capturing the human figure, and the codes it is wrapped up in, you are offering us a slice of time, an entrance into a certain mentality. Do you discover new potential or gain a new awareness when going through the archive and addressing certain topics anew?

Ari: Absolutely! Twenty years ago for example, it was really difficult to picture someone with tattoos. It was awkward, intimate and even a bit indecent to ask people if they had them. Now, I hear colleagues from Berlin state ‘Skin is the new fashion’. Everything is skin at this point – we are at the climax of the mouldable and manipulable body. It has just become another tool to work with. The so-called norm-core black T-shirt is just a border or a frame for the real artwork applied to our own bodies. You go off to Turkey to get hair implants, or fly to Thailand to work on something else. Nowadays you shop for your body. Shopping is a cultural experience that constantly boosts our self-image. It’s great! – and also so crazy! It is something indefinitely tied to the city. The urban environment presents this landscape of possibilities.

To use the trending term fluidity, our bodies are no longer straightjackets we have to adjust to. It’s the other way around; we are showered with shows about make-overs, and items on gender change have made their way into popular media. However, we should be cautious of a backlash. Freedom and acceptance are things that continuously need to be championed and never taken for granted.

Nowadays people display many more layers of identity. Even if they are part of a scene – it is no longer people focused on that one particular identity. It’s more of an emulsion of all these elements from different scenes. We are in a moment in time that is defined by transition and crossovers between cultures, ages and sexualities. In contrast to the past all these different groups and individuals now have the ability to connect with each other online; to get recognition and latch on to a certain identity. This makes it even more important than ever to keep connecting in real life – and on the streets as well.

Nathalie: This is an interesting remark; I can imagine this presents a dilemma in your own practice. After all, as a photographer, aren’t you at risk of reducing people to their image?

Ari: This is the fine line. I want to capture people how they really are. At the same time I am interested in subjects who have the ability to rise above their individuality. People who can become a symbol for a larger unit, the archetype intrigues me. This is something that exists in a space of tension between categorization and individuality. I don’t enforce anything at the moment of the shooting. Most of all, I make sure people are comfortable, explaining the premise of the picture, giving them the floor as their stage and then just let it roll. Shy people you might need to encourage a bit, and extravert people sometimes need to get their little act over with at first. There’s always a point that people fall in position, when they let their guard down and settle into their true posture. There is something very natural and self-evident about posture that is fascinating. It is a magical moment when someone finds his confidence and reveals this ‘Bring it on’ attitude.

Ari Versluis and profiler Ellie Uyttenbroek have worked together since October 1994. Inspired by a shared interest

in the striking dress codes of various social groups, they have systematically documented numerous identities over

the last twenty-one1 years. Rotterdam’s heterogeneous, multicultural street scene remains a major source of inspiration for

Ari Versluis and Ellie Uyttenbroek, although since 1998 they have also worked in many cities abroad.

They call their series Exactitudes: a contraction of exact and attitude.

Nathalie: That particular look, the pro-vocation ‘Bring it on!’ is so apparent in the image Original Gabber, 1994; I believe it was the very first image in the Exactitudes series that you started together with profiler Ellie Uyttenbroek in 1994. You see this bold challenging guy, he is kind of aggressive, but also so, so seductive!

Ari: This particular subculture has been infused by a ‘We’re here to stay’ mentality. You have to imagine that the movement shook the foundations of dance music. There was this whole peace&love kind of house-movement going on in Amsterdam at the time, you know, think of all these poppy Micha Klein VJ-sets and xtc-culture and then all of a sudden – there was this dirty, loud and unapologetic hardcore from Rotterdam. It’s wonderful, when you capture people on a point of great heights, when their posture exudes pride. The apotheosis of youth or being elderly, or anything in between. It is rare to encounter people whose appearance completely coalesces with their moment of life who are completely able to be who they are at that moment in time. Doesn’t that just scream celebration!

That’s why I like to work with genuine people. I mean this in terms of the non-professional, in contrast to models who have been taught generic expressions that should convey certain emotions. No matter how hard you try, you always feel it’s fake. On this front we’re experiencing a substantial shift; on the one hand there is a growing number of modelling agencies that are embracing the realness, yet at the same time it’s becoming more and more difficult to capture real people amongst ordinary people.

Nathalie: That sounds very ambivalent. I would say ‘ordinary’ means something like ‘general’ or ‘unassuming’, which confuses me because your work’s specific quality is about taking the ‘normal’ to a next level. Highlighting details that make us special. Or are you talking about real as an opposition to artificial?

Ari: The visualization that is connected to globalization is present at all levels of lifestyle, from food culture, to interior decoration, and also self-imagery. It’s all so generic! So many visual codes now are standardized and present all over the world. Everything is charged with a kind of emotional expectation that is continuously mimicked and reproduced. I notice this especially when trying to capture images of young people who adhere to a kind of sensual template that erodes the sense of spontaneity. It’s a challenge to get to the teen or the child within. In the nineties, kids also wanted to portray themselves in a certain way, and maybe reached out to two or three poses and then it was over, the template was used up. Now it is entrenched in their whole being. They have become experts in analysing their own social media accounts and continuously remodelling their self-image. As a photographer I see it as a plight to unpack this encoded behaviour and undress it to get to the unmediated self. It is truly quite eerie how difficult it is to get teenage girls to close their lips for a photo.

Nathalie: You also work in fashion and advertising, which are industries absolutely entangled with this urge or necessity to ‘be desirable’. Does this conflict you – is there a way of working around these standards of sensualization?

Ari: Mostly I am invited by brands that recognize my vision, so there is not really a conflict. Brands like Vetements, who are not interested in submission in a model, but rather a type of aggression I would say. It’s essential that the models have a talk-back quality, that they are not trapped in an image and offered up to the viewer, as victims for wandering eyes. Fashion has two sides; there are parts of the system I despise and would like to avoid altogether. On the other hand, when you wear it well, when you understand what clothing is doing for you… Well that’s about power. Silk has this effect, and also leather or a pair of the toughest jeans; an asymmetrical cut to a dress. The models need to have affinity with what they are wearing, it does not matter how handsome they are. You need to look for characters, not beauty. Confidence is the number one source of attraction, and fashion, photography and clothes can help you figure that out. It is in service of, and not a goal in itself. This creates sensuality rather than applies sensuality for other means.

In advertising, the codes I have to pay attention to are quite variable, especially in the corporate world, such as in the assignments that I have been commissioned by the large worldwide recruitment company Randstad for about fifteen years now. In this work, it’s not the authenticity of the models that counts; it’s much more about knowing the different dress codes in the corporate field in each country. If the blouse has one more button open in France, the whole photo shoot is gone, while this one button can just add the sophisticated touch to a campaign for the Netherlands. So you have to be aware of these fashion codes of conduct and take them seriously when implementing them in the planning and execution of the photo shoot.

Nathalie: Is there a way that you counter this standardization due to globalization? You travel a lot – are places really so much the same then?

Ari: It is important to see how style transitions in different places. You can’t experience this through the web. You need to be there. Cities are different in terms of presence and sensuality, even if there is a lot of sameness. There is a certain kind of refinement that you cannot get anywhere else but in Milan, for instance. These are things that need to be felt bottom-up if you want to contribute to a richness of images.

Imagine experiencing a piazza with your eyes closed: what happens in that moment? You can almost smell the people around you, hear the decisive click-click of heels, hear the leather or the soft tingling of jewellery. That’s sensual! When you open your eyes, you see it matches the image you have in your head. 0r sometimes, haha, not. Now you have started something, a gaze, a form of communication. So you nod politely and maybe get a smile in return. We realize too little that people who have invested in their appearance are open to acknowledgement. Inviting someone to look at you, to take you in – not only in a polite bourgeois way, it can also be fuelled by aggression or as a challenge – this locking of eyes and allowing another to investigate your appearance that can be hot, without being intrusive. These are the sensations that make life tingle, it’s the vitamins for civilization.

Nathalie: Would you say there is a difference to experiencing these exchanges during the daytime, or the night?

Ari: Ha! For twenty years I’ve lived in a part of town that used to be the red light district; it is all offices and embassies now. The ladies of the night used to welcome people with the phrase ‘You are now entering the Bermuda Triangle’. It was one of those places where you would go out to get cigarettes and not return for two hours. Very unpredictable and serendipitous. Now all over the world these girlie bars are losing terrain. We are losing our sense of adventure. You can visit New York, armoured with 52 apps that will lead you around any kind of danger. But aren’t we still aching for that spontaneous encounter? Nightlife plays a very important part in this. It functions as the touchstone for our daytime selves. Some nightclubs, especially in the gay circuit, are unimaginably important for many people. These places allow us to role-play all kinds of identities, or guise them instead. It’s so important to have these spaces, where you can invent who you are, or want to be, ‘in the real’. It’s a welcoming ground for experiments and transitions and this serves a very vital purpose in cities with many cultures and newcomers. It weaves the fabric of a city. I believe these cultural experiences are just as necessary as having museums.

…I have experienced moments that were truly großartig…

Nathalie: So is there a place where these cultural experiences collide? I mean, a museum is a monument and safe-keeper of cultural expression and it seems the nightlife is its ephemeral counterpart – that benefits from its ability to disappear again.

Ari: It might sound strange but trying to capture the ungraspable has been a motivation that somehow springs from my fascination with the city of Rotterdam. I have always felt that there aren’t enough chroniclers around to make sense of this crazy working-class city. It’s a feeling I have always carried with me. I have experienced moments that were truly großartig here. I think back on this crazy club Carrera that was around in the eighties and had a revolving dance-floor. It was a dark almost black discotheque where I experienced this urban vibe for the very first time. An astonishing gathering of ages, cultures, styles. The city’s nightlife was in some way absent at the time so people came from all corners. No one told them to do so, it wasn’t marketed. They just all came to be there and dance. It was tribal! Events like these have in some way or other informed my work and driven my practice. Through the encounter with people and the engagement, it seems that I can touch these cultural moments. My way of working denies the anecdotal, this is also tangible in regards to nightlife. Some stories are best left to the night.