Working across performance, film and installation, artist Tai Shani has steadily developed an intoxicating mythology. Drawn from Greek myths, science fiction, queer theory and feminist activism, her fictions trouble categories of gender, provoke a revaluation of foundational stories of humanity and excavate deep collective trauma. A literary language permeates the work and probes the limitations of words to convey the extremities of human experience, from bloody violence to erotic ecstasy. Early performances, deploying text, performance and sculpture, formed the basis for her epic multi-part series DC Productions (2014–19), which over years established a city of twelve archetypal women whose looping, troubled stories are accompanied by strange architectural and sculptural forms, and staged as tableaux vivants. Her most recent work, The Neon Hieroglyph (2021), is her first entirely digital project, and takes as its focus ergot, a psychedelic fungus that grows on bread and which offers a gateway to new fantastical visions of potential societies.

Natasha Hoare: You started out in fashion photography. How did the transformation in your practice particularly in regards to writing come about?

Tai Shani: From a young age, writing has interested me. When I was very little, I started writing poetry. My dad also wrote. My parents were hippies – well, my dad was a drug dealer – but apart from that, he was a writer. He trained as a lawyer and then became interested in writing. He wrote about the law, and did a series of radio plays in Israel before he left about important revolutionary trials. So, he was very encouraging and really wanted me to pursue writing.

At eighteen, I began studying photo-graphy, which lasted a couple of years. One day, after leaving a crit session in a heartbroken rage, I decided to never go back to school. But my final piece actually involved text. Looking back on it, there is that early relationship with language. Tel Aviv is where my interest in fashion began. Although, that also started during my teenage years; it felt like a glamorous world. In the nineties you had a lot of women photographers like Corinne Day who were offering a different way of presenting fashion. That was interesting – that there was the possibility of creating alternative narratives. Nan Goldin’s photography was a heavy influence on me, for example. My work had nods to subculture, and narrative, and it was quite cinematic. Fortunately, there was someone that I knew quite well who opened a gallery in Tel Aviv, and one night we were talking, and I mentioned my final art school piece – the one that I had walked away from after the disastrous crit session. She invited me to do a show of that piece, and from that moment on it was like a breakup. I took maybe two pictures after that, and that was it for my photographic practice.

When it came to art-making, I didn’t use texts for a very long time. Then, in 2008, I did a performance – a hypnosis session – which involved a text about someone whose identity folds over into different heroines from different narratives. It was as if something had shifted, and it felt right to me to go back into writing.

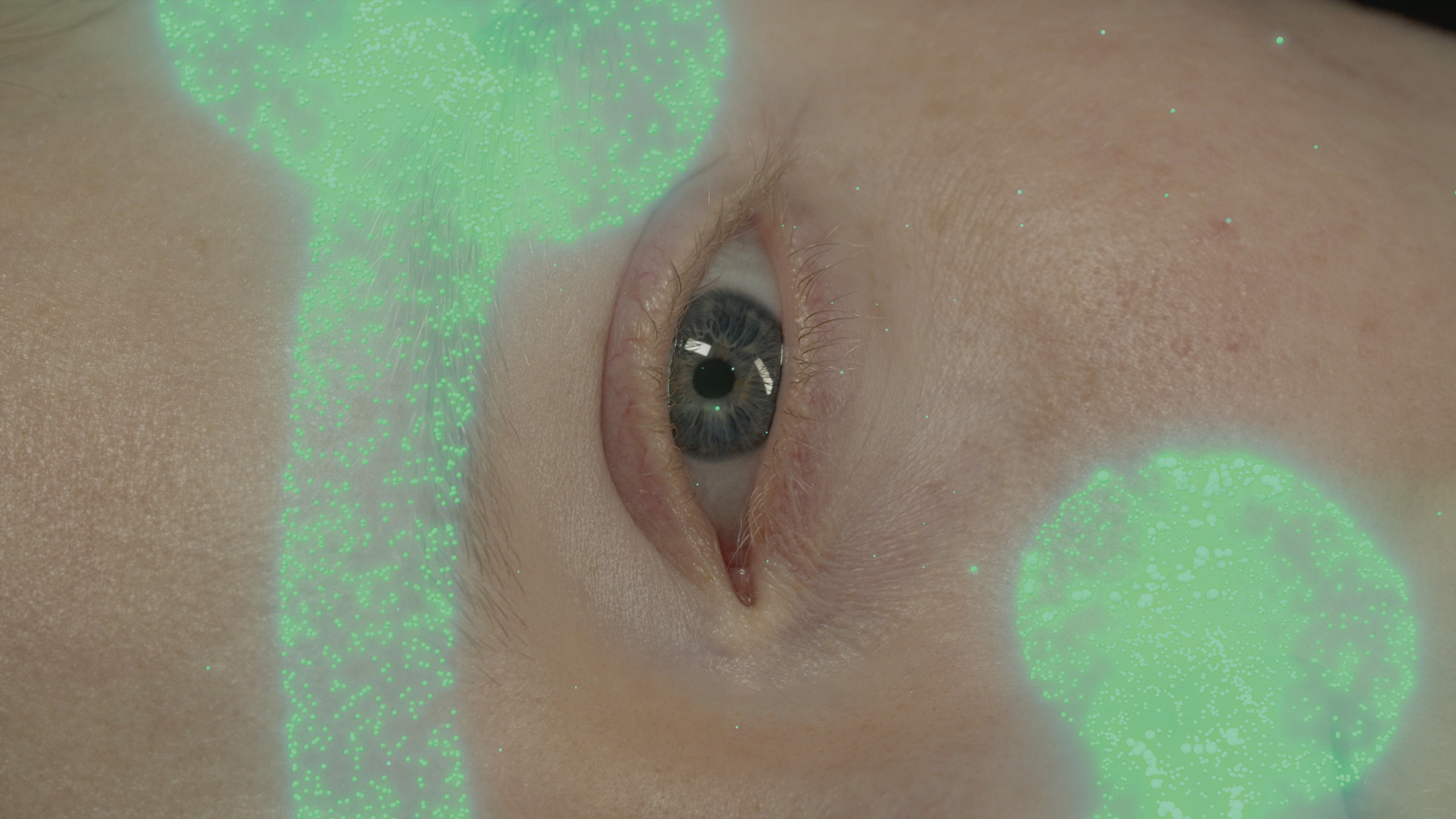

The Neon Hieroglyph, 2021. Video still courtesy of Tai Shani

Natasha: And where do you think your desire to create alternative worlds comes from?

Tai: Growing up in (what the adults there thought of as) a utopian project in Goa, India, was problematic. In many ways it was a colonial project, but from a countercultural perspective. However, there was another side – not the ignorant side of it – but one interested in thinking about building a counter-hegemonic society: a completely different way of relating to each other and what life could be. This didn’t become apparent until we moved to Europe. Then I had this realisation of how regimented people’s lives were, particularly those of children. In Goa, we didn’t have television or anything like that. A lot of us didn’t have electricity in the house. When Michael Jackson’s Thriller came out in 1982, I heard about it through a frame-by-frame retell from some kids – we loved recreating the scenes of the music video. Play was very much a part of how we related to each other as a group. We had a lot of science fiction as well. I was fortunate to have experienced an extremely unconventional set-up that has made me more open to that. But I was always attracted to the idea of impossibility and magic, and to the notion that the miraculous can emerge at any moment. With films or art, my interests have been informed by that sensibility. My friend Pia Borg has said that if you look at the history of cinema, you have Georges Méliès who created within the fantastical and explored the possibility of the imaginative, and the Lumière Brothers as the ancestors of documentary, the quotidian or capturing realism. At the birth of the medium, there are these two ways of relating to the process of creation: the fantastical and realism.

…I was always attracted to the idea of impossibility and magic, and to the notion that the miraculous can emerge at any moment…

Natasha: That’s a beautiful genus. You’ve mentioned how much science fiction has meant to you. Which writers do you specifically look to for inspiration, and what do you think the potential is for sci-fi in terms of political transformation?

Tai: I’m not reading very much at the moment, but it has definitely shaped me. When I was young, my dad’s third wife was really interested in science fiction, and she gave me books as soon as I could read, including Pamela Sargeant’s The Shore Of Women (1968). That book is very essentialist. I wouldn’t necessarily recommend it. The premise of it is based on a separatist society – it’s very binary, I don’t feel it’s politically interesting in today’s gender context. Women live in the city and the men live outdoors and hunt and do ‘masculine’ things.

There are temples where the men pray to the goddess, which they do through making love with a hologram, and that’s how the women collect sperm to procreate. It was mind blowing to me at the time.

I was really into Doris Lessing as well. There are lots of things that you read in science fiction that act like pieces that are missing from a system. Once you add those absent parts, all the cogs start moving. There are ideas that operate in that way, which activate the political. That is the main wonder of science fiction: it’s not just about living differently, it’s that you take these tools, and you can apply them to your everyday. It is a type of critical thinking. As a form, it brings in the possibility of writing ideas into the world that don’t have to be contingent on reality. For example, the questions of ‘Who would build it? What is the technology needed for this? How do we get there?’ are often absent. You can just state that in this world these things happen. Maybe it’s more about the kind of thought processes that these narratives activate for me, than it being some kind of benchmark. There are of course writers, like Ursula K. Le Guin, Octavia Butler and other feminist authors, who propose incredible worlds in which to think about gender differently. And that’s just one function of their writing; they also create narratives that act like pivots, that make you turn your thinking around. Some Soviet science-fiction films about capitalism are so lucid and edifying. I think as a genre it’s often been used as a tool for political thinking and transformation.

Natasha: I am interested in your use of classical mythology, because it has this curious flip side. It can be read as a foundation stone of the Western tradition, with all those attending problems, but it’s also full of examples that disobey those codes of socialisation.

Tai: Yes, it’s both those things. There’s an affective level to it – these very archetypal stories that are woven into the matrix of Western civilisation.

But what’s interesting is they often have parallels in other cultures as well. It does compel me to think about how it was to live within the imagination of that time. That imaginary would have been so pure for those writers and theatre makers. My imagination is so crowded by history. But at the same time, there is something in these stories that just doesn’t age – they maintain heat. Antigone is a really good example, as one of the most adapted stories in Western theatre. And the reason why is that all the questions it raises are still so relevant; whether you obey the rules of the state or your own morality, these ideas will never not be relevant.

I like to think across a very broad timescale. One of the characters that consistently comes through in my work is the Neanderthal. I’m interested in what we are; the development of subjectivity at different points. My biggest hope at the moment – in terms of technology and the future – is that when I’m really old I’ll be able to spend my last days time travelling, wearing some kind of VR suit that offers you sensations of what it could have been like at different points in history.

It’s important to retrace history as a feminist project. History is multiple, and it has multitudes, and you can trace certain lineages through it that are of interest to you. We must not conceptualise of it through dominant narratives, which are all ideological anyway. Mythology is history and is often ideologically co-opted by political movements. I think it’s important for counter-hegemonic, ideological positions to be reclaimed in that history as well. It doesn’t have to be presided over by patriarchal thinking, such as the hero figure. I’m more interested in the minor characters that represent more contemporary ideas, not just in terms of their actions or their narratives, but also the kinds of stories that were written around them. For example, in The Metamorphoses, Ovid describes how the sirens became liquid, right down to their fingernails. That’s a really visceral image, and it’s not the most well-known passage, but to me, there are these moments that still hold that mesmeric power.

Natasha: I am reminded of Ursula K. Le Guin’s A Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction (1988) where she repositions storytelling through a feminist lens, proposing an alternative to the narrative structure of the hero. I really enjoyed another piece I found on your website called The Idle Eye and the Stone Idol (2004), which starts with this amazing erotic tale of a woman being held in the hand of a giant Poseidon. She climaxes in the crook of his thumb. What role has the erotic as an imaginary played in your work?

Tai: Sexual eroticism has been central to my practice. My writing is always interested in bringing into language those experiences that live on the margin of an ability to be articulated. How do you write about the erotic or desire in a way that isn’t cheesy, or reductive? How does one write about the experience of the interior of a mouth?

That story of Poseidon came from a dream I had when I was really heartbroken. My position in terms of what I think is useful for a feminist project has changed over the years, but The Idle Eye and The Stone Idol was metabolised into early DC Productions. A lot of my texts get repurposed. There was something about capturing the erotic in a very explicit graphic way, that felt to me at the time (I don’t know if I feel that way anymore), like truth. I wanted to be graphic and explicit about violence; about sex, about self-consciousness, in a way that was completely unflinching. This also allowed me to represent gender in a different light, because when I began writing, it was always in a binary: with a woman protagonist. But throughout DC Productions, I had an opportunity to reimagine those characters, and really think about gender through the text. Sometimes the characters have no genitals, or have genitals that change, so that their gender became a lot less fixed. It opened up a space to think more broadly about gender, using different pronouns, for semen, for ejaculation, to explore what lived lives

are really like.

Natasha: DC Productions is an incredible unfolding project that spans years and multiple characters. What provoked it, and what holds you to working in long format?

Tai: Many years ago, I wanted to do a PhD on the epic even though I don’t have a BA. My proposal was the epic as a ground for feminist realism. Those ideas were percolating behind the scenes for a while. Prior to DC Productions, I was working in a hurried, chaotic, but epic way already. The performances were large scale, with many bodies. I had a lot of energy in those days. I started writing a Roman orgy performance that would last twenty-nine days centred on twenty-nine characters, but no one was interested in commissioning it. At the time, I had just finished an intensive performance about Bluebeard’s seven wives. I was uneducated in academic feminism, but I had all this anger and rage, and an invested sense of injustice around a lot of these issues. I just didn’t have the language to communicate that or put it into action.

I was always interested in the figure of the actress. An actress is a performance, a gender performance, a constructed subjectivity. If you think of Be, Be The 7 Darknesses: A Very Gothic Reading (2013), it’s a feminist tale as well. In that work, there are all these building blocks, almost like in an animation, where components come together to create something solid.

Back then, I had started reading about medieval mysticism and I came across The Book of the City of Ladies (1405), by Christine de Pizan. The way she depicted her allegorical city resonated with me. I was approached by the curator Stephanie Rosenthal to propose something for a show called Mirrorcity at the Hayward Gallery in 2015, and I decided to use it as an opportunity to start building my own city. It started with three characters: the Neanderthal, the Mystic and the Woman on the Edge of Time, who is named after Marge Piercy’s speculative fiction. I wanted to see if it feels right for me to write big projects, and I found that the length of that process gave me time to really realise things. An artists’ practice can be understood as one, long project in itself, but that way of working provided an episodic structure to reflect back on.

DC Productions builds a utopian or post-patriarchal city, looking at all of the foundational structures of what a city or citizenship is. Who are the people that live there? What is their history and what would you think of it? How would you fit their biology? What would you think of their conceptualisation of nature? And how would all these things come together? DC Productions offered up a useful and productive way to think about historiography. In dominant narratives, the past is presented as a plateau of information, with a spotlight that runs through it that creates a sequence. But why can’t history be democratised as everybody’s experience? In DC Productions, there’s a database called the eternal cortex, which is an archive of every single lived experience. There’s no dominant history, instead there are multiples that can be accessed through different AIs.

That posits questions such as: What are the animals that we talk about in the city? Why do we think of kinship with lions? Why can’t we have kinship with a Mexican whiptail lizard, which reproduces through parthenogenesis? These were really generative things to think about. It could have gone on forever, but I eventually wanted to move on. And, after having some distance, I suddenly realised that it was about finding a way to create a space to talk about trauma; both typical trauma and extraordinary trauma that’s often involved in gendered and sexual violence. And that that’s where the audience connected with it. How we talk about art is so based in these ideas. But people were responding to it in a deep and profound way. In imagining, and bringing into a shared space, we can transform these horrific things into some kind of power.

…In imagining, and bringing into a shared space, we can transform these horrific things into some kind of power…

Natasha: The project is populated with some incredible characters. I found the vampire figure particularly touching. There was something very beautiful about the idea of an undying body at the bottom of the ocean, alone and aroused by orgasms generated by plankton. The violence in this, and in other characters’ stories, such as the protagonist of the audiovisual soliloquy Paradise (2017), who stares straight at the viewer while speaking about her gushing climaxes, there’s a closeness between sex and horror. There is a sense in which women use violence for revenge, but also, you seem to be amplifying the harm done to women under patriarchy. Is that true?

Tai: I think it’s both things. Well, there’s three actually. Violence has tended to be a masculine-dominated action, and one that in more traditional forms of feminism would have been seen as a complete no-go. When I did my first really graphic piece, Be, Be The 7 Darknesses: A Very Gothic Reading – I struggle to read it now as it makes me queasy – people really pressed me as to why it was so violent. And why this was enacted on the woman’s body. For me, it’s a question of why minoritised subjects (and I no longer think white women are really so much a minoritised category), have to be better and good. Why can’t they be bad? Why is that burden on me to not think about violence? Also, it’s a very basic reading to say, ‘you’re just creating more violence in the world.’

I mean, violence is there all the time. As we’re talking now, people are being bombed in Gaza. Violence is always context specific, isn’t it? That safe space that you think you’ve created – it’s a fiction.

I was also interested in exploring some of the ideas around silence and the limits of experience. Again, this idea that writing is a way of rendering silence in language. In many ways, writing about sex can be like writing about violence – you need to be able to undergo an unflinching approach as the author and also as the listener, for it to have traction and not just be procedural.

I was in analysis when I wrote that text, and I was aware that a lot of the decisions I was making as a writer were often guided by a policing voice that said something was too expressive, or tacky, or garish. I really wanted to be more uninhibited in my making. So, it began as an exercise. I wrote about violence in order not to flinch. I gave myself permission to disobey. Detailing violence is difficult, but it’s also something that happens when you use a poetic register, like describing a splash of blood as looking like lace. I found it useful to take a completely different tone to talking about something, giving shape to this new imaginative space. It became the stylistic thread throughout the work; as well as an ability to transgress my own boundaries.

In some of the stories the violence is more explicit, like Phantasmagorgasm (2017), where ghosts emanating from a decomposing body become a symbol of the patriarchal. In Paradise, there’s a sense of rage and of wanting to retrofit retribution. I guess revenge is definitely a fair description. One of the reasons why therapy is so useful – and I’m not saying this work is therapeutic – is that you put something into language. The medieval mystic character – is bursting to speak, but this piece of coal blocks her bodily. Once something becomes reified in language, it’s like an act that exists in the world. It’s almost comparable to when centuries-old frescoes are uncovered, and the oxygen that hits the dyes means they disappear in front of the excavators’ eyes. I love that story, you know, about archaeologists finding these rooms that were incredibly vividly coloured, and all the colours suddenly begin disappearing. In a way, trauma can be like that as well. Once it is spoken aloud, it becomes something else.

One of the reasons I wanted to move forwards from DC Productions, was in recognising that aspects of the work were autobiographical, and Paradise is very much part of that.

DC: Semiramis, 2018. Courtesy of Tai Shani and Glasgow International 2018. Photos: Keith Hunter

Natasha: That metaphor of the disappearing frescoes is beautiful.

I wanted to ask how you have moved past this work, to use your public platform, especially in the wake of the Turner Prize, in different ways?

Tai: It doesn’t feel right to position myself as a ‘come with me’ kind of voice anymore. Throughout the project my understanding of feminism and the construction of the body, through black, trans, queer and intersectional feminism, has made me reconsider my position in those politics. I’m now following other people, and my politics are benefiting from the scholarship of others. I think they should be credited for leading these politics in the arts and in academia. I’ve slightly pivoted what role I, and my work, have. I am lucky enough to have access to, and to talk about things that I think are important, and those issues don’t need to be in the work. I want to advocate for things as a citizen, and I want the work to dive into a mystery, and bring back affects unknown.