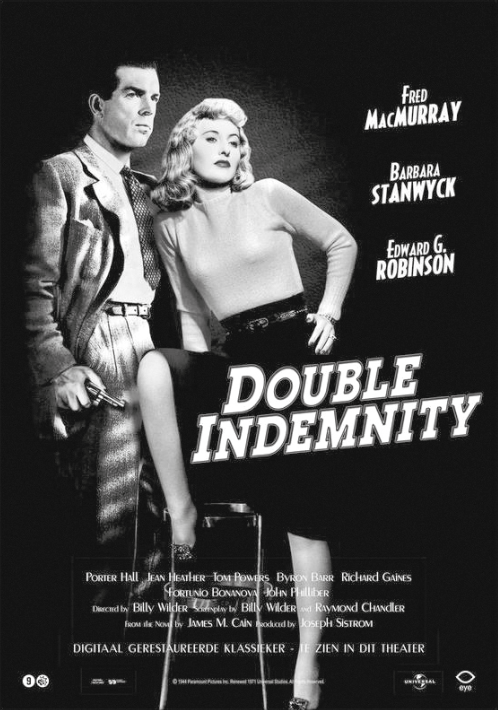

Double Indemnity (1944), directed by Billy Wilder.

Nº1 •

Femme Fatale

In an iconic scene from Billy Wilder’s 1944 thriller Double Indemnity, Barbara Stanwyck appears nearly naked, wearing only a towel and a glossy layer of red lipstick. Her lips – which are lustrous, wet, and so palpably scarlet as to make you forget the fact the film is shot in black and white – provide a clue to her character’s nature. Stanwyck plays a woman who kills her husband and seduces another man, but we never actually see her go to bed with him. Forbidden from depicting sex or murder on screen by the Hays Code, which remained in place until 1968, Wilder relies instead on many sensuous shots of Stanwyck touching and retouching her lips, as a kind of placeholder for intercourse, and for violence. After an adulterous cinch with her husband’s life insurance salesman, we see Stanwyck curled, cat-like on the sofa, lazily reapplying her lipstick in a compact mirror. The viewer searches her lover’s face in vain for a lipstick smudge, but his skin is curiously unmarked. Stanwyck’s character, we assume, is too slick to leave a trace.

The association between lipstick and temptation stretches back to at least the fifth century, when medieval churches were typically decorated with devils, pictured in the process of painting their lips red. Elevated to the status of a dark art in Renaissance England, cosmetics were thought to have such a bamboozling effect on the male spectator that, in 1650, Parliament tried to pass a law that would make the use of cosmetics to ‘deceive an Englishman into marriage’ punishable as ‘witchcraft.’ (Witches, it has always seemed to me, are the original femme fatales.) Barbara’s blood red mouth, which is ascribed a kind of hypnotic power in Double Indemnity, exemplifies a dangerous historical tendency among women to use make-up to get what they want.

During the 1700s and 1800s, it was in vogue for Japanese women to blacken their teeth with a stain and adorn their lips with a green lip gloss made from safflower.

Nº2 •

Behind the Curtain

The bewitching sight of a woman applying her make-up became an object of fascination for the Japanese artist Gion Seitoku, who painted a series of courtesans between 1789 and 1830. In Woman Applying Make-up (1820), Seitoku depicted Geisha using a small stick to paint their lower lip green, in a style known as sasa-iro beni (bamboo grass red), achieved by using red make-up (beni) derived from safflower that turns an iridescent green when thickly applied. To reveal the labour that goes into the process of making one’s face up, instead of depicting his subject perfectly coiffed, Seitoku shows her at work, a look of almost painful concentration on her face. Seitoku was known in Kyoto for the realism of his portraits of women, which is partly attributable to his habit of peeking behind the curtain, and revealing the artifice and skill that goes into the creation of a fantasy.

Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1863), which scandalised the Paris Salon in 1865, similarly pictures a woman who uses make-up intentionally, as part of a game of seduction in which she is an active participant. Olympia’s eyes are lined with kohl, and her lips are obviously rouged. Like the ribbon around her neck, Olympia’s make-up serves to make her nakedness more brazen. The viewer can’t flatter himself that he has caught Olympia unawares; she looks frankly out at him, having prepared her face in advance to meet him. You get the feeling that if anyone is set to profit from this encounter it will be her, and not you.

From 1980’s red kisses to the man in

Der Fensterputzer (1997) who uses his rouged mouth to paint women’s fingernails, lipstick is a recurrent prop in the neo expressionist work of Pina Bausch.

Nº3 •

Glamorous Crying

We like to look at women doing their make-up (the hundreds of millions of make-up tutorials on YouTube proves it). There is also a curious gratification to be found in the image of a woman in a state of dishevelment; in the sight of all that make-up running down her face. The photograph Larmes (1932) – or ‘Tears’ in English – by Man Ray shows a woman gazing plaintively upwards, her cheeks studded with jewel-like teardrops, rounded and glistening. This photograph is an attempt to explore emotion as an aesthetic experience, enjoyable for both the viewer and perhaps even the crier herself. Probably inspired by Man Ray, fashion houses in recent years have been experimenting with the idea of glamorous crying, with Gucci and Acne Studios sending models out on the catwalk, their faces streaming with crystal tears.

One rather more joyful exploration of make-up, and its tendency to run, comes from the German choreographer Pina Bausch. In her ground-breaking production 1980, there is a sequence in which a woman repeatedly kisses her dance partner’s face, covering his cheeks in fabulous red welts. Instead of giving us a woman in lipstick who is attempting to convey poise and impossible perfection, Pina presents make-up as something exuberant and delightfully sloppy. Lipstick smudges are a visible sign of passion. With her lips a woman marks her territory, and leaves an intimate tattoo on her lover’s skin.

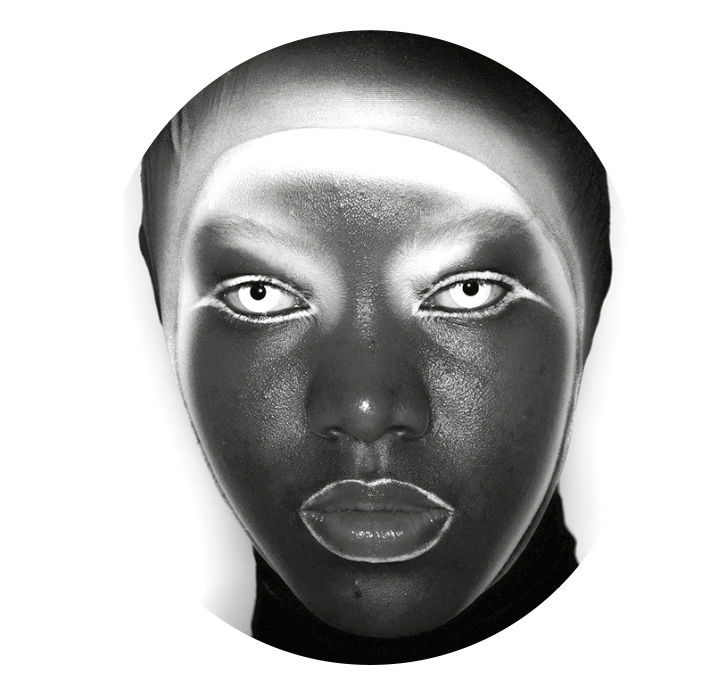

One of Berlin-based make-up artist Leana Ardeleanu’s striking looks.

Nº4 •

Trash Make-up

The make-up artist Leana Ardeleanu has conducted a series of striking experiments with the mess you can make of your own face. She smears mascara down her cheeks and applies lashings of runny red lipstick, before carefully layering tufts of toilet paper on top, a playful take on ostentatiously chapped lips. In one striking look, Ardeleanu moulds a false layer of skin and adds it to a model’s forehead, to create the impression of alien-like deformity.

Fashion photographers often stage deliberately ugly make-up shots, using actual rubbish (cracked egg shells, discarded mushrooms) as cosmetics, to refigure the human face into a perishable, and sometimes viscerally unpalatable, work of art. In my favourite trash make-up photograph, the artist Julie Lee reimagines her own eye as a piece of shellfish. Two pink, scaly prawn shells are affixed to her upper and lower lashes, to construct a beauty look that is at once repulsive and strangely sensuous.

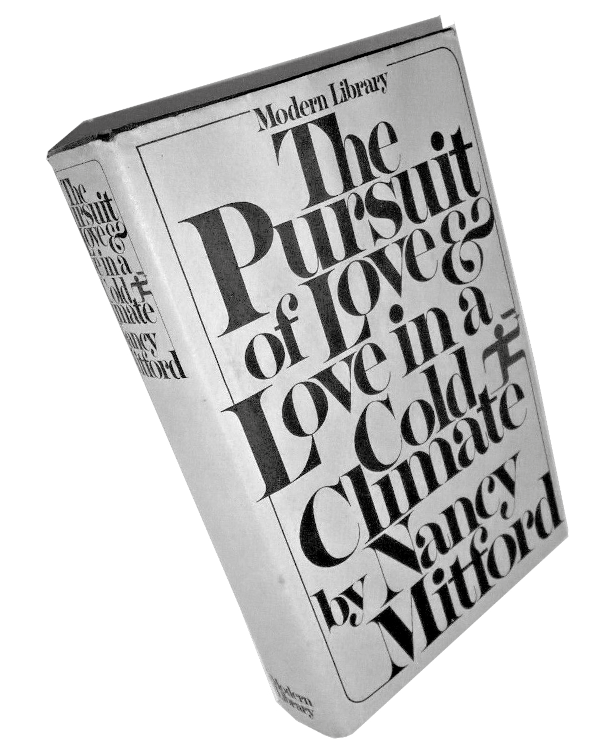

Nancy Mitford’s 1945 novel follows the aristocratic Linda Radlett in her quest to find true love. Her desire for romance results in dabbling in DIY cosmetics and rebelling against the stiff upper lip of convention.

Nº5 •

The Pursuit of Love

In The Pursuit of Love, Nancy Mitford’s delicious 1945 novel about her own eccentric English family, two women get their make-up badly wrong (by accident). Linda and her cousin Fanny – who have learned the rudiments of sex from a copy of Ducks and Duck Breeding – have secretly driven to town for the afternoon, in the desperate hope of finding romance. On the street, they catch sight of their own faces in a window, and begin to experience pangs of regret. Cosmetics, like pre-marital sex, being forbidden to aristocratic young ladies, the girls have used acrylic paint to colour their eyelids blue, and caked their noses in baby powder.

Convinced that any make-up, no matter how dreadful, is more seductive than wearing no make-up at all, Fanny and Linda go to lunch looking like this, snatching surreptitious looks at themselves in every reflective surface they pass on the way. ‘When women look at themselves in every reflection, and take furtive peeps into their hand looking-glasses, it is hardly ever, as is generally supposed, from vanity,’ Mitford wrote, in lines that recur to me almost every time I look at myself in a shop window. It is ‘much more often from a feeling that all is not quite as it should be.’

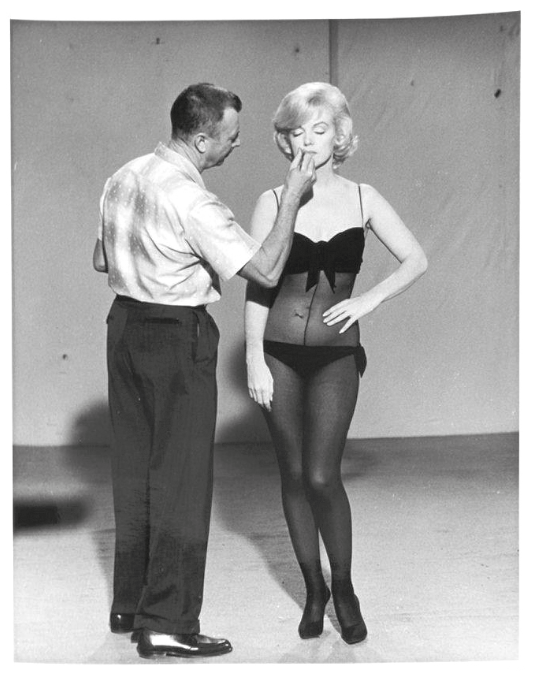

Marilyn Monroe on the set of Let’s Make Love (1960) together with her beloved make-up artist Allan Snyder.

Nº6 •

Marilyn

This truism – that the women who gaze at themselves most compulsively do so not out of pleasure but, rather, anxiety – is perhaps best illustrated by the example of Marilyn Monroe, who was so invested in her own appearance that she sneaked her long-time make-up artist Allan Snyder into hospital with her in 1953, to powder her nose. Snyder had perfected a technique of dabbing the tip of Monroe’s nose with blush in order to create the illusion that was even more charmingly upturned; a trick so valued by the star that she left special instructions that Snyder should make up her face on her death bed, requesting that he get there while she was ‘still warm.’ Snyder’s other innovations included cutting Monroe’s false eyelashes in half, so that her eyes might appear still more beguilingly hooded, and adding a pinprick of red to the corner of each of her eyes so that her eyeballs looked whiter.

Monroe understood more than most people that make-up can act as a kind of screen, so dazzling it prevents people from actually seeing you. ‘All my life I’ve played Marilyn Monroe, Marilyn Monroe, Marilyn Monroe,’ she said to Henry Hathaway in 1960. ‘I’m doing an imitation of myself.’ The roles she longed to play – complicated, imperfect women like Eugene O’Neill’s Anna Christie, and the protagonist in W. Somerset Maugham’s Rain (1921) – did not materialise. When Monroe died in 1962, she was eulogised, as she is now, not as an actress but as a sex symbol. Her intense interest in her own make-up, like her lifelong habit of cutting up photographs she felt did not flatter her, suggests a conflict: between wanting to preserve the mirage of her own image and wanting to destroy it. Allan Snyder did indeed attend to Monroe’s face on her deathbed (she had an open casket). He also served as one of her pallbearers.

South Korean rapper Beenzino has two perfectly aligned beauty marks under his left eye. The symmetrical moles are coveted by K-pop fans.

Nº7 •

Beauty Marks

Of all Marilyn Monroe’s signature features, her beauty spot is perhaps the most ravishing – this slight defect on an otherwise flawless body serving to accentuate her allure. At the height of Monroe’s stardom in the mid-1950s, women up and down America were meticulously pencilling on their own fake moles. A ‘Monroe’ mark has a very specific geography – about ¼ of an inch above the upper lip on the left-hand side of the face – but the convenient thing about a DIY mole is that you can move it about to suit your purposes. Beauty marks make superb disguises for blemishes, an acknowledged fact since the smallpox epidemic in 1700s Europe, when it became fashionable to carry around a ‘patch box’ full of fake moles, which could be artfully arranged to conceal unsightly pockmarks.

In Chinese medicine it is traditional to read a patient’s fortune in the peculiar constellation of their moles, much as you might read a palm. A chin mole, for example, is thought to indicate stubbornness, and a mole on the tip of the nose is a sign of enormous sexual desire. Though less formalised, there is a similar custom in the West of assigning symbolic meaning to the placement of your beauty marks. In 18th century France, moles became a tool in a secret language of courtship. Fashioned out of taffeta, silk and, sometimes, mouse fur, beauty marks were worn by both men and women to send specific signals: a mark on the cheek was a sign that you were open to flirtation, a mark on the nose implied roguishness, and a mark by the eye meant you were already in love (and therefore out of the game). The shapes a beauty spot could take became fantastic and infinite, with tiny moons, stars, hearts, squares, dots, flowers and ships worn in aristocratic circles. There is even a record of a beauty spot specially designed to look like a tiny horse and carriage.

Made of buffalo hide, the ‘skin’ of wayang kulit are painted in vibrant, luscious colours, with each shade signifying the essence of the puppet’s character.

Nº8 •

Wayang Kulit

In wayang kulit, an Indonesian form of shadow puppetry, cosmetics are used to write an even more intricate code. One of the oldest existing theatre traditions in Asia, wayang (ancestor, deity) kulit (skin) uses hand-painted puppets made out of animal hide, held between a light source and a screen to tell epic stories of good and evil.

Master craftsmen are tasked with painting the skin of these immortalised ancestors and gods, and the colours have symbolic meaning. The smaller the figure, the more exalted its state of consciousness, with heroes marked out by their almond-shaped eyes and black-hued faces or bodies, which signify a capacity for serenity and self-control. Larger puppets, by contrast, tend to be coloured red, a sign of their impulsivity and intemperance. They also typically have mottled foreheads, protruding eyes and luscious lips.

Wayang kulit puppets cannot be understood as art objects or ornaments, although they are intricately painted. Rather, the painting of their skin is part of a ritual that opens up a portal between the living and the dead. The shadow puppet master is perhaps best understood as being akin to a shaman. He brings alive and gives voice to spirits and gods through the recitation of ancient legends and cosmic tales. The screen on which the shadows dance is like the veil between the spirit and everyday world, and the puppet master can aid and influence the forces which cross it.

Author of Love Style Life (2015), photographer and blogger Garance Doré writes about fashion in sensuous detail. The book also features her stylish ink illustrations.

Nº9 •

Handbags

A woman’s handbag, too, can act as a kind of portal – perhaps not between the land of the living and the spirit realm, but between the wearer’s past and future self. Typically lined in pale pinks, grey and warm flesh tones, the inside of a much-loved purse has a womb-like quality; it is a secret place, filled with objects unique and precious to their owner. To own your own bag is a coming-of-age ritual curiously linked to adult womanhood (remember how glamorous and mysterious your mother’s handbag appeared to you as a child?).

The fashion blogger Garance Doré recently wrote that she loves her new bag so much she wishes she could ‘sleep inside it.’ This desire to sleep inside the bag is a desire to escape, to live in another possible world. Mary Poppins captured imaginations with her miraculously expanding carpet bag, and I often have the feeling, rummaging around in mine, that I could fall into it. The bag is also, very often, the place where make-up is kept: a miniature perfume, a hair brush, hand cream, lip balm and emergency mascara. Carrying it around on your arm, you can open it up and enact miniature transformations, emerging from a busy metro carriage, or a restaurant toilet, as a whole new person – sweet smelling, powdered and elegantly turned out.

Evelyn Waugh’s witty, satirical novel follows Dennis Barlow’s infatuation with Aimée, a naïve Californian corpse beautician.

Nº10 •

Death Masks

The connection between the living and the dead becomes the unlikely subject for romance in The Loved One (1948), a comic novel by Evelyn Waugh. Our hero, Dennis, an Englishman adrift abroad and working at an American pet cemetery, falls in love with Aimée, a cosmetician at the human morgue down the road. Aimée’s prodigious skill making up dead faces is part of what makes her so irresistible. She lathers lifeless cheeks and contours bloodless skin like an artist, ‘intently, serenely, methodically’. Dennis and Aimée’s first encounter constitutes one of the most surprising lover’s meetings in English literature:

‘She was what Dennis had vainly sought during a lonely year of exile.

Her hair was dark and straight, her brows wide, her skin transparent and untarnished by sun. Her lips were artificially tinctured, no doubt, but not coated like her sisters’ and clogged in all their delicate pores with crimson grease; they seemed to promise instead an unmeasured range of sensual converse. Her full face was oval, her profile pure and classical and light; her eyes greenish and remote, with a rich glint of lunacy.

Dennis held his breath. When the girl spoke it was briskly and prosaically.

‘What did your Loved One pass on from?’ she asked.

‘He hanged himself.’

‘Was the face much disfigured?’

‘Hideously.’

In Pedro Almodóvar’s 1993 black comedy, Kika is hired to make-up the corpse of Ramón, but he unexpectedly bounces back to life. Naturally, they become lovers.

Nº11 •

Back to Life

The relationship between a make-up artist and a dead body is taken one step further in Kika (1993), a comedy about a cosmetician by the Spanish director Pedro Almodóvar. Our eponymous heroine is hired by a grieving father to make up the face of his recently deceased son, Ramón. But as Kika applies foundation to Ramon’s chin, something peculiar starts to happen: his eyelids flutter, and his beautiful lips begin to twitch, and he comes back to life.

Kika ends up in a ménage à trois with the father and his reanimated son, slipping secretly from one man’s bed to another. But the most arresting scenes in this film aren’t about sex, they’re about make-up. Painting a face, as Almodóvar shows us, can have unpredictable consequences. Transformations do not always turn out as planned. Make-up is a ritual with a magical, sometimes unsettling power. You can use it to conceal a flaw or ensnare a lover, but you might just as easily end up reanimating a corpse.