I first met Simon Stephens when he conducted a workshop with a group of young directors at the National Theatre Studio in London. He gave us chunks from his latest play, ‘Carmen Disruption’, which had no stage directions at all, and told us to stage some of it as we saw fit. To entrust precious new material to some thrusting young theatre-makers is not every writer’s instinct, but it perfectly sums up Stephens’ collaborative generosity.

I seem to remember that we murdered every scene. But by the end the playwright had gained something genuinely worthwhile from our thrashings, which had unconsciously taken a more continental approach to the text, which is to say enormous liberties with it at every turn. Somehow Stephens writes with razor precision of trapped lives, charged cities and with overpowering sensory detail. He has managed to embrace the freedom of European directing and as a result is one of the most international of the young British playwrights. As his play Song From Far Away tours the Netherlands and his adaptation of Threepenny Opera opens in London, I meet him on a roof in Shoreditch. While he tears into a huge bacon sandwich, I attempt to probe deeper into the increasing eroticism and complexity of his work.

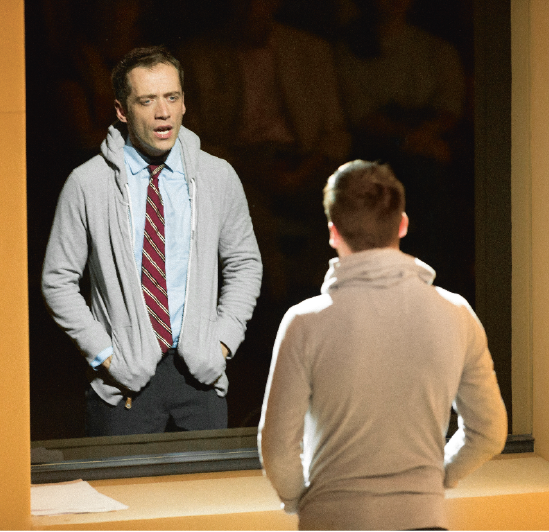

Song From Far Away, 2016 Courtesy: TGA /Photo: Jan Versweyveld

Tim Hoare: Is it true that you got into theatre in order to attract girls?

Simon Stephens: That’s a crude sim-plification of it! But fundamentally it was true and fundamentally it kind of remains true. That was why I first went into the theatre, because I wasn’t raised in a family where the experience of going to see serious theatre was expected. The serious drama I grew up with was television drama in the eighties, and serious cinema: films like Blue Velvet and Taxi Driver, the dramatic force and the tension of those stories astonished me. The live art I would engage in would be music gigs in Manchester. I fucking loved that, the unpredictability, the visceral nature of that. Then, at university, all the most beautiful girls came from exotic places like Surrey and Buckinghamshire and wanted to be actresses. I’ve always had a thing about posh girls. In a pathetic, misguided and ultimately fruitless attempt to meet these girls I’d go and watch their student productions of really god-awful plays. But even sitting watching I remember thinking, ‘I’m not going to meet these girls and I hate this play but this form has potential.’ If you told a story like Taxi Driver in a room like this you can synthesize the heat and potency of a dramatic story like that with the unpredictability of a live gig and that could be fucking incredible. Fundamentally that is all I’ve tried to do for twenty-five years. Twenty-five years of trying to synthesize Taxi Driver and Mark E. Smith in an attempt to pull posh girls from Surrey.

Tim: You once said that a huge amount of creativity has been driven by the libidinous engine of sexual desire.

Simon: It’s true. We tell stories for all kinds of reasons, we make art for all kinds of reasons: serious, political, philosophical considerations, emotional need, to complete interruptions and make sense of things that confuse us. We tell stories to explore our terror and to make sense of our sadness. I make plays that I wish other people had made so that I could go and watch them. On top of all that, we peacock. When you write, you write with the hope that somebody will read what you’ve written and think, ‘God, you’re a great person to mate with.’ There’s very few experiences as erotically charged for me as the experience of seeing, happening to be a straight man, a beautiful and talented actress give of herself to make something that I’ve imagined in my head become real. If you think about what that actually is, it’s like you have a dream and then the most beautiful and talented people in the world, sexy fucking glorious people, work for months to literally make your dreams come true. That’s definitely erotically charged. You always fall in love with actresses. In the early days of my career it was really destabilizing because I’d find myself thinking, I’m absolutely in love with this girl. Then I realized that it was just bullshit. But having acknowledged that it was just a consequence of the rehearsal room then I could go, ‘All right, this is happening again, this is great, I love it, I love it and it’s beautiful.’ I would never act on that source of attraction, but it’s there and it’s brilliant. It makes the room alive, it makes the room playful. You’ve got to have a rehearsal room that is playful and alive, you don’t want to fucking sit around the table talking about political meaning, that would be so dead. You want to rise to each other.

There’s very few experiences as erotically charged for me as the experience of seeing, happening to be a straight man, a beautiful and talented actress give of herself to make something that I’ve imagined in my head become real.

Tim: Is it fair to say that your work has grown more comfortable dealing with the erotic, as opposed to the sexually explicit, as you’ve matured?

Simon: I think that’s probably fair. In Song From Far Away the sex is actually quite chaste. There’s a moment in Song From Far Away where the protagonist is going to go and shag the Brazilian guy in the hotel and it’s like a Mills and Boon novel, you know, the door closes and then it reopens again and you come back in afterwards with him lying on his chest, I love the tenderness of that.

But something like Carmen Disruption, which is really sexually explicit, about masturbation and Skype sex, prostitution and anal sex – you don’t find that in my earlier plays. Motortown is maybe the first play when sexual activity is more frankly discussed.

Pornography is the stark and shattering play by Simon Stephens that captures Britain as it crashes from the euphoria and promise of the 2012 Olympic announcement into the devastation of 7/7. Each monologue or playlet focuses on a different individual, walking in their shoes in the run-up to the tragedy. The play was first presented in 2007 in Hannover, Germany; the UK premiere was in 2008 as part of the Edinburgh Fringe Festival.

Tim: Why do you think that is? You mentioned before that in the eighties as a student there was a sense that confessing to an erotic force in yourself would be seen as politically incorrect.

Simon: That’s definitely true. I think due to the nature of feminism at the end of the eighties, and I’ve talked to peers of mine about this, there was a notion that just acknowledging that you were attracted to somebody felt a little like raping them a little bit. Andrea Dworkin famously said all men are rapists, and operating at that time really felt legible to me. I think that you could make an argument that that’s disappeared almost too much, you go to undergraduate environments now and it’s like a fucking wet T-shirt competition and I think that’s more problematic probably. But I think you get older and one’s relationship to sex and sexuality changes. There’s something interesting in the relationship between sexuality and procreation. It gets to a point where I’ve had my kids now, I don’t want to go again. I don’t need to impress anybody, I don’t need to peacock for anybody, I don’t need to get a mate, I’ve mated, that’s all done. Then sex becomes something that is an act of friendship, familiarity and trust, you get less embarrassed about it. Becoming less embarrassed about it possibly meant I felt like I could write about it. But I’m also writing plays in an age of internet pornography. The words ‘erotic’ and ‘magazine’ bring up memories of the existence of things like Playboy and Penthouse which is something that as a fifteen-year-old in the eighties you’d see on top shelves. You’d go into a newsagent and dare your mate to get something from the top shelf and see if he can get it and not die of shame or embarrassment. That’s changed massively now, clearly. Thirteen-, fourteen-, fifteen-year-olds have got quite hardcore sex on their telephones in their pockets, in their classrooms. It’s not necessarily a change for the better. I’m not saying that the eighties relationship to pornography was healthy, it was just a different type of unhealthiness. But I write on a computer where, if I get bored, I can easily access internet porn, two clicks away without even thinking. I think that’s omnipresent, for everybody, and that fascinates me as a thinker.

Tim: You said of your play Pornography that we live in ‘pornographic times’.

Simon: I think that’s really true. I think it permeates all the narratives we tell each other about the culture we live in. There was a line in Song From Far Away about the underwear adverts in Amsterdam.

Tim: About how confusing that was for Willem, the main protagonist.

Simon: Yes, exactly. Go out in London here and look at the images you see. Somebody once showed me a brilliant article in a German cultural magazine that was headshots of women in adverts interspersed with headshots of women pretending to orgasm in porno movies. You had to guess which was the advert and which was the porno movie, and it was impossible. Advertising uses the same semiotic culture that has come from porn because it’s there, it’s in the phone, it’s in the iPad, it has become everywhere. There’s an intellectual interest in dramatizing that, but also it’s accessible when I’m writing. I’ve never had gay sex; as it happens I’ve never had sex with a man so how do I write about the sex scene in Carmen Disruption? I’ve never hired a male sex worker, I’ve never had a female sex worker as it happens either, how do I access that? It’s not fucking difficult, if I want to find out about what it’s like to have gay sex it would take about two minutes.

Tim: There’s a sense in your play Pornography that what we’re often told is erotic is in fact deeply un-erotic.

Simon: Yes, and it’s dehumanizing. That was the interest in Pornography; it’s the comparison between the pornographic gesture and the terrorist gesture to dehumanize the subject. If you’re a terrorist you can’t take a bomb onto a public transport system and be concerned about the humanity of the people whose face you’re going to blow apart. If you’re making or watching porn you can’t care about the humanity of the person you’re watching. There’s a brilliant joke by Doug Stanhope, he’s an amazing American stand-up comic. Talking about the despair of his time, he said, ‘If you ever doubt that humanity is a fucking mess, carry on watching the porno after you’ve cum.’ I think that is a great joke that cuts to the quick of the fundamental dehumanization and lack of erotica that you find on something like PornHub.

Tim: Going back to Song From Far Away, Willem seems full of repressed urges and desires that the play often externalizes only to brutally cancel out. There’s something amazing about the way Willem can’t tell his ex-boyfriend all of those beautiful words, which he does actually share with us in the monologue, and instead simply makes a horrendously awkward sexual advance.

Simon: With the character of Willem that emotional inarticulacy and psychological tentativeness is a consequence of his family, his life and his relationship to money and growing up in a small town. Amsterdam is a major city, but in international scope it’s a small town. It’s a consequence of his parents and the psycho-dynamics of his family. The moment in the play that I was really moving towards is the moment when his dad says, ‘You come back and you don’t even care.’ But we’ve seen how deeply he cares, how massively he cares, having seen through the nature of a monologue told entirely from his point of view. And what I was attempting to do at that moment is dramatize the disconnection between how we assume he’s behaved and how other people perceive him behave. Our perception of him at the funeral is that of somebody in awe and in love, and everybody else’s perception is that he just goes and stands there and he doesn’t say anything or do anything, it looks like he’s disconnected from the whole thing. Nobody sees his awe at the fireworks display; the audience sees it but his parents, his sister and his niece just think he watches it and fucks off early.

Song From Far Away, 2016 Courtesy: TGA / Photo: Jan Versweyveld

Tim: We find ourselves sympathizing very deeply with a man who to his family legitimately looks like a prick.

Simon: That was our interest, that was Mark Eitzel’s interest and my interest throughout was to really excavate a deep well of humanity in the person who instinctively we would hate more than anybody else. You’ve got a songwriter and a playwright, two middle-aged men thinking, ‘who is the person you’re going to most hate?’ We chose the highest level of venture capitalist, who has no emotional connection to his work, who buys and sells cities. If art has some moral responsibility in a culture which is dehumanized in the way that we’re talking about, if it has a function it’s that it can remind us of humanity, which sounds desperately sentimental but I actually don’t think it is. I think that’s our job.

Tim: The antithesis of dehumanization seems to be genuine sensuality and physical connection. Like the revelation Willem experiences when he eats his mum’s chicken.

Simon: Yes! Or the moment when he sees the fireworks or the water, the snow melting into water. Or imagines the earth on the coffin.

Tim: Is it deliberate that in many of your plays the major premonitions, connections and realizations are almost always couched in sensuality? Alex’s vertigo when he swims over the sea wall, or the widow in Pornography smelling meat as she walks home with blood in her shoes, or the mother touching her baby’s stomach, or Escamillo’s extraordinarily heightened senses when he follows a woman through the streets?

Simon: I think that is a sound reading of a lot of the plays. It’s not necessarily a cognitive choice. But on the other hand it is cognitive to not do other things, it is cognitive to not articulate epiphany through political thought. Or abstract poetry. It’s real, it’s concrete, it’s human and alive.

Tim: It’s visceral.

Simon: It’s visceral. It goes back to what we were saying about what rock and roll did for me. That’s what theatre can be, it can be direct, visceral and human. I’ve never thought of it as being a sensuous thing in terms of ‘I’ve got to get the smells in’ but actually I fucking love getting the smells and the tastes and the sounds in. It inspires me as a thinker and I think it’s through sensuality that we can reach audiences and create imaginative spaces for them to understand themselves and one another in a way that, if you did it through a political idea, which is what other writers might have done, I wouldn’t get as excited. But if you did it through an abstraction, which is what still other writers might have done, I wouldn’t get as excited. I get excited when a woman comes to learn, understand her position in the universe by the feeling of her skirt on her legs or whatever. It’s a Joycean thing, I guess it does come from Joyce or Proust.

Tim: T.S. Eliot talks about how the writer’s mind is ‘constantly amalgamating disparate experience’; how we might connect the smell of cooking with a particular emotional memory.

Simon: Yes. Maybe in that sense I’m still writing under the legacy of Proust, Joyce and Eliot. I never fucking think of that because I just think of myself as writing under the legacy of Mark E. Smith and Martin Scorsese. But you look at Taxi Driver, compare that to reading James Joyce’s description of someone in a café eating a plate of peas in Dubliners. Then you imagine Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver in the café where he’s just sitting and there’s a bunch of cabbies all sitting and eating, while the way they eat communicates the smell of that place. Travis never has a moment where he explicitly states, ‘I’m lonely as hell, and I can only feel connected if I kill people, so I need to do the right killing and kill the pimp.’ But the film lets you experience what it’s like to fire a gun that shoots somebody’s hand off and leaves him with one finger. That’s the same connection as Proust and Joyce.

Tim: In a play like Carmen Disruption your writing is almost overwhelmingly sensuous. A character like Escamillo or Carmen himself, he talks about the blood that gets in between his toes when he’s kicking a man’s head in.

Simon: Yes, or the blood on the hand of Alex when he holds his daughter’s head in Sea Wall.

Tim: Reading Carmen Disruption is a sensory overload; it’s completely intoxicating. Do you have to foster that sense? Do you walk around cities having the same experience as Escamillo? Is it occurring to you that vividly?

Simon: In my life I’m not thinking like that, that would be overwhelming. But when I’m working, generating material for a play, then yes. I develop strategies for finding that. When I was starting off in the nineties my wife got me a Dictaphone and I would wander around Edinburgh where we lived talking into it, because the gesture of walking through a city and thinking generates thought in a way that excites me. I always felt a bit like a dick, or a spy, but nowadays you feel like a weirdo when you’re walking around a city and you’ve not got headphones on or you’re not talking into a phone. You feel like you’re actually fucking strange. Now I just use the voice memo on my phone, and I go for walks and I just talk, like a constant stream of consciousness into my phone. The chorus from Carmen Disruption comes pretty directly from the things that I said into my phone.

In the opulent grandeur of a European city, a renowned singer abandons the opera house for the truth of the streets.

A gorgeous prostitute. A tough-talking taxi driver. A global trader. A teenage dreamer. Everyone’s looking for something.

Simon Stephens’ play reimagines Bizet’s opera Carmen and the possibility of love in a fractured urban world.

Courtesy: Almeida Theatre, London

Tim: Which city did you choose for Carmen Disruption?

Simon: London, although it’s a deliberate corruption because there’s part of Zürich in there and parts of other cities.

Tim: In the play there’s a general homogeneity to all European cities as a result.

Simon: Exactly, yes. European cities are homogenizing themselves.

Tim: Do you feel like, in spite of that, there are towns in Europe which have a different sensuality and a different impact on the nervous system?

Simon: Physical geography exists even in urban spaces; Manchester is still cold and wet, Madrid is hot but dry, Barcelona is hot and damp, Florence is hot and rainy. That physical geography will lead directly to political geography and to psycho-geography and those three things will kind of relate to one another and permeate around one another. Madrid is a horny city in a way which is different to London being horny or Oslo. Oslo is erotic because everybody needs to get hot, Madrid is erotic because everybody needs to take their clothes off.

I’m interested in something different to that, I’m looking for spaces that are more sensual or more subliminal, which operate on the subconscious level.

Tim: I think there is a really powerful physical and sensual quality to your writing. Does that attract a different kind of production?

Simon: I think there’s a generation of playwrights, an important generation of playwrights, that I revere and respect, for whom the theatre was a political space of dissonance and defiance. The responsibility for those playwrights was to speak the politically unspeakable and articulate ideas with a clarity that came out of Brecht. It’s been fascinating working on Threepenny Opera. The deus ex machina at the end of Threepenny Opera is something we always resisted but it’s only in the last few previews we realized that it’s in that moment that Brecht finds absolute political clarity. That gesture of finding political clarity is fundamental to half a century of playwrights who came up after him. I’m interested in something different to that, I’m looking for spaces that are more sensual or more subliminal, which operate on the subconscious level. It’s different, too, from ‘in-your-face’ theatre. To me it’s more like back-of-your-head theatre: you experience something and you’re not necessarily conscious about what it is. But then it will live with you for a time afterwards. We operate in a culture that is more eloquent and narrated than the culture has ever been. There’s more words written about this culture and you can access more words about this culture than you’ve ever been able to. In our pockets every moment there are hundreds of thousands of words being used to articulate what’s going on in the world. There was a generation of playwrights for whom the fundamental action of theatre was to articulate the world in words. The critic Michael Billington is constantly asking what a play says; he’s looking for the linguistic or the literary gesture. For me, theatre can be something different to that, which is to evoke human connection in a disconnected world through what it is to feel. And that can be a sensual or an erotic or a visceral experience. When it is, that’s as political a gesture as any other gesture you might make in a speech or a statement. That invites directors who are excited by that, so the productions will tend towards that.