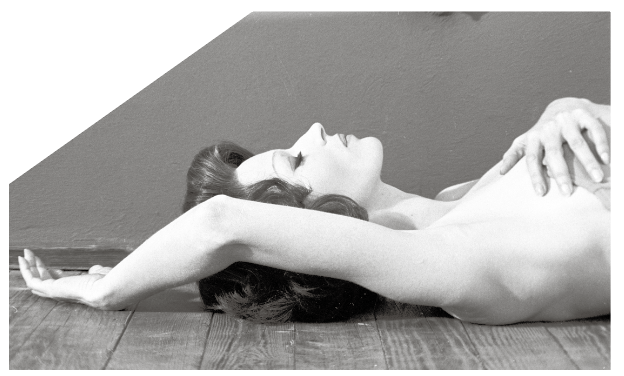

Silvana Mangano in Teorema (1968)

© Reporters Associati – Roma

Nº1 •

Cinema as Refuge

In a 1969 interview in Lyon, France, Pier Paolo Pasolini describes his masterpiece Teorema (1968) as a mysterious theorem, a problematic parabola, argumentum ad absurdum or an apagogical argument. Put informally, this refers to an argument that establishes a statement by proving that the opposite would end in absurdity. In the film, a model bourgeois Milanese family, comprised of a mother, father, son, daughter and maid, receive a visitor whose relation to them is not revealed. His identity kept foggy, except from what the viewer assumes from the books that he’s reading: a young, good-looking and well-read man. In the interview, Pasolini claims that the stranger’s visit is marked by a visceral encounter with authenticity. The moment this man glides into their lives, the whole family descends into crisis. And the contact with and to authenticity happens through sex. The man fucks the whole family separately. He fucks the daughter, the son, the mother, the father and the maid, then he leaves. This sexual intercourse leads to a bundle of extreme situations. The daughter goes into a catatonic state, the son becomes a painter; the mother leaves everything behind and starts picking up young boys from the street for sex. The father also abandons his life of luxury, starts sexual relationships with men, eventually falling into madness, and the maid becomes a saint with healing superpowers.

Teorema proposes an open theorem by providing a scenario where everything changes immediately, once and for all, after just a single contact with authenticity. It’s a theorem that describes how sex can awaken the inner desires of a group of people, resulting in status and family bonds coming to a violent end. It’s as if they were asleep and they wake up to explore and expose their absolute singular realities – a liberating force triggered to release individual mysteries that sum up all human mystery, overdubbed by the eloquent music of Ennio Morricone.

It might be considered rather odd to begin an exploration of the sexual undertones in Arabic songs with a reflection on Teorema. It may not be related to the topic, just like the opening sequence of Billy Wilder’s masterpiece The Seven-Year Itch (1955), where we see Native Americans sending their wives away during a heatwave in Manhattan. This sequence has almost nothing to do with the actual film, except for establishing the location and weather. However, The Seven-Year Itch introduced the iconic clip of Marilyn Monroe standing over a subway grate, where the air of the passing trains blows her dress upwards. It may not be politically correct by today’s standards, but what immortalised this clip is the sexual connotation that can be immediately translated to a strong image of ‘the blonde’ airing her vagina during the hottest summer in Manhattan.

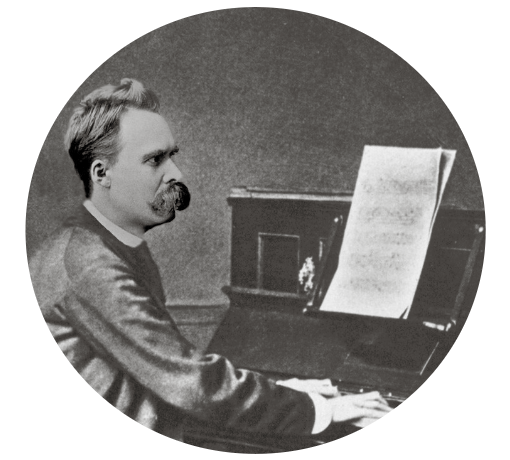

Friedrich Nietzsche proposed that great music is tied to myth-making, the suppression of reason and the Dionysian, sensual aspects of human nature.

Nº2 •

Music and Myth

Music was and still is at the heart of cinema. Before cinema was able to talk, it had music: a sort of spectre that enveloped the seen and the unseen, matter and non-matter. In place of spoken language, musical scores over silent films had a broader ability to overcome linguistic obstacles across cultures, translating meaning to audiences around the world through emotion, psychology and entertainment. Music was also a refuge that hid what was not accepted at a certain time, alluding to desires in the dark.

What is the source of music’s ability to infiltrate physical or cultural barriers, and fill the ether with imaginary objects? Maybe all these unanswered, recurrent questions are some of the reasons why music is sometimes considered a dirty product of creativity. The truth of this attribute is reflected by the fact that it is one of the most censored forms of art throughout history. Music is luxurious, religious, mythical, ceremonial, traditional, popular, folkloric, absurd and rigid, static and dynamic, familiar and strange, pure but not puritan. It is transcendental if anything: able to save lives and yet end others – potentially resulting in ruinous consequences for its most avid devotees.

Music has henceforth absorbed most, if not all, of the forbidden subjects in modernity, the same way, in ancient societies, it tackled all inexplicable matters of life. Music shares an intrinsic connection with the origin of the myth – all those stories of repeated damnation that nobody takes seriously anymore. In early civilisations, music surfaced alongside religious rituals, celebrating life and death and the worship of natural phenomena that couldn’t be rationalised. Although, it seems clear that myths still form an essential part of our in-built or hardwired, universal settings, and their parables continue to manifest in the present day. Yes, maybe as Nietzsche hypothesised, this high level of irrationalism in music is an inherited baggage that has been carried along since its early relation to the myth.

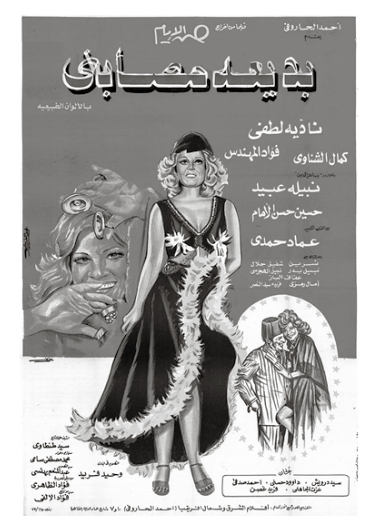

Badia Masabni

Nº3 •

In the Darkness

In a rare TV interview dated from 1966, the seventy-five-year-old Badia Masabni, an actress, dancer, singer and founder of Egypt’s first cabaret in 1926, asks the interviewer if she can stand up to perform one of her old songs titled ‘In the Darkness.’ The elderly lady starts to dance and sing to a happy, jumpy melody:

In the darkness

How beautiful is the darkness?

The heart gets happy

How beautiful is it?

At home

In the cinema

And everywhere

When the song is over, she looks at her old friend, the oudist Farid Ghosn, and asks him, ‘Do you remember when we first did this song together?’ He replies, ‘Thirty or thirty-four years ago.’ This places the composition of ‘Darkness’ in the 1930s, in the early days of commercial film, meaning that this is perhaps the earliest Arabic song where cinema is mentioned. This same intimacy found in the heart of the darkness of the cinema theatre also infiltrates the sphere of nightlife that Masabni pioneered. Masabni led the way in the field of entertainment after dark – she discovered and launched the careers of the most important and legendary belly dancers, such as Samia Gamal and Taheyya Kariokka. But she was also boundary-breaking as an individual – she once claimed that she was the first female in the Arab world to cut her hair short, drive a car and fly in an aeroplane. Subdued lighting at home has a sensual connotation, but the darkness of the cinema has a stronger and more figurative meaning: that’s where privacy in public is ultimate.

When radio became central in diffusing music beyond the exclusive environment of cabarets and nightclubs, censorship started growing, as artists self-sanitised their work, and society at large put limits on what was acceptable. There were subjects allowed to be aired and others forbidden. Censorship became more systematic. So, artists had to compromise. And I like to think that musicians had to compensate by creating more and more suggestive and affective meanings.

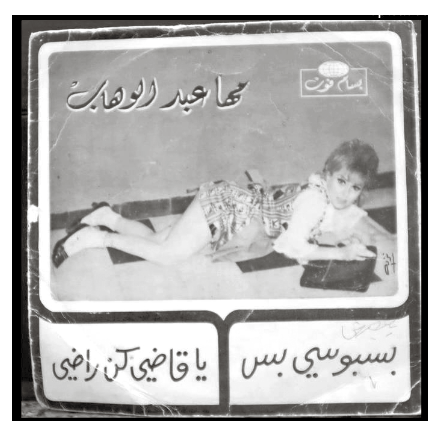

On the sleeves of her records, Maha Abd El-Wahab appears poised in glamorous lingerie or cocktail dresses, gazing amorously.

Nº4 •

Rub Your Moustache on My Lips

Maha Abd El-Wahab was a Syrian singer who found small fame in Lebanon during the mid-1960s and early 70s as ‘the singer of sensuality.’ She wrote and composed the handful of singles she released – which was unusual at the time – and appeared in suggestive poses in her nightwear. She also put out the solo album Reflections of the Near East, released in the United States in 1963. And acted in the 1966 black-and-white spy thriller Interpol in Beirut, alongside Taroub, the Syrian–Jordanian singer and actress.

Abd El-Wahab’s records were banned across most of the Arab world for their explicit lyrics and her sensual style, but by the 1970s her tapes were being circulated under the table. Over an improvised oud melody, her voice reverberates with a haunting echo effect, the lyrics spoken softly in a Syrian dialect:

I saw you in my dream

You opened the door

and entered

And you came next to me in bed

And you started kissing me from top to bottom

My heart started beating

and beating till I woke up

To find that my dream is true and you are here next to me

Come and kiss me, come and kiss me, ahh ahh umm ahh

On another record she sings:

Rub your moustache on my lips

Let me listen to you moaning

I knew Abd El-Wahab’s name before I heard her music. She used to pop up in light jokes during conversations between my father and his friends about their adolescence. As a teenager, I was intrigued to find out more. Later, I discovered that she adopted the family name of the legendary composer and singer Mohammed AbdelWahab without having any relation to him – an ambitious move, probably meant to suggest the quality of her music. Some years ago, I found a couple of her records at the flea market and learned they were in high demand because of their rarity and uniqueness. However, while the covers look appealing, the excitement soon fades away once you play them – the lyrics are not as expected, nor the music. This is a very good example of how obscenity can dissipate with time, turning into a sweet memory instead of a forbidden fruit. By today’s standards, Abd El-Wahab is kitsch rather than taboo.

Taroub rehearsing with a music group in Cairo during the 1960s.

Nº5 •

Hairdresser, Do a Fringe for Me

Amal Ismail Jarkas was born in Damascus in the late 1930s into a conservative Circassian family. Soon after moving to Lebanon in 1956, she adopted her stage name Taroub, which translates to ‘a girl full of joy,’ derived from the word tarab meaning to shake from happiness or sadness. An Arabic term that describes a state of mind caused by an external event, tarab is the psychological effect that occurs after receiving specific information. It can be used to speak about the reaction from receiving either good or bad news, but it’s mostly used to encapsulate a positive state of mind. Another definition for tarab is the joy of being in pleasant company. Its meaning can stretch further to express the collective higher state of consciousness that people share following experiencing a moment of ecstasy – a light trance. Tarab is also widely used as a musical attribute connoting the joyful and ecstatic feeling of classical Oriental music, and it has been utilised to refer to the genre itself.

Shortly after the start of her career in the mid-1950s, Taroub formed a duo with the Lebanese composer and singer Mohamed Jamal, whom she also married. The couple became one of the most famous duos in the Arab world. Sadly, the romance did not last, and their collaboration ended a few years following their divorce. Undeterred, Taroub moved forward alone. ‘It was very hard to launch my solo career as a female

artist… The most hurtful critic that I still remember is when someone wrote that I sing with my legs,’ she told me when we met a few years ago for a coffee in Beirut. Now in her eighties, she has since quit singing and has chosen to wear the hijab. Though her music wouldn’t be considered controversial by today’s standards, she is still remembered for being bold and risqué. Other than being one of the few female artists to write her own songs, Taroub was the first to break the static performance pose behind the microphone, instead choosing to dance euphorically in a mini skirt on stage while singing:

Please Hairdresser,

do a fringe for me

To cheer my heart

To tease the son of our neighbour

Who’s always looking outside

His eyes are always looking both ways

Oh God, what beautiful eyes

I wonder how come he is so tall

He absolutely blew my mind

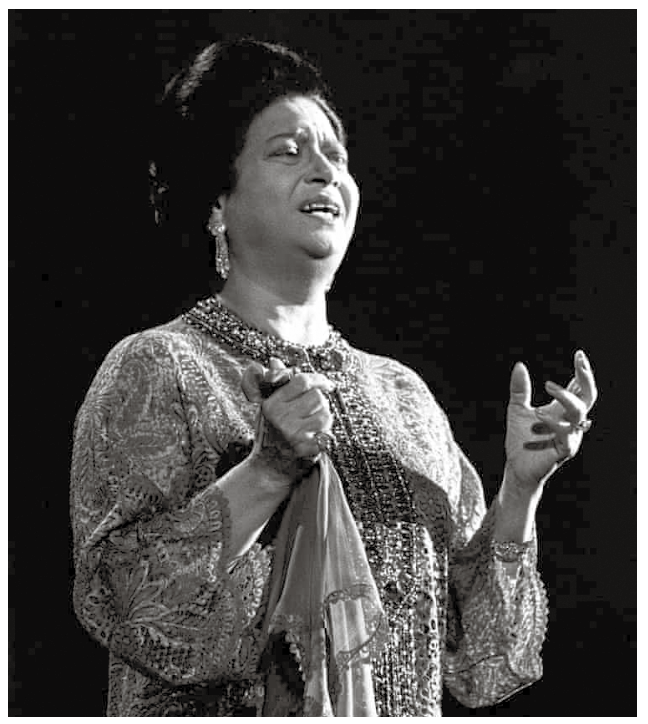

Umm Kulthum is considered one of the greatest Arab musicians who ever lived. For over fifty years, she stunned the Arab world with her unmatchable voice. Her lyrics were written by poets who eagerly offered their pieces to her in hopes of becoming the next esteemed songwriter ordained into Umm Kulthum’s repertoire.

Nº6 •

A State of Trance

Theatre Qasr El Nil, 5 March 1970. Over rapturous applause, the speaker announces: ‘The curtains will open to the star of the east, Umm Kulthum and her orchestra are to present her awaited song ‘‘Wa Marit El-Ayyam.’’ Lyrics by the poet Ma’amoun El-Shinnawi, and the latest composition of the musician of the generation Mohammed Abdel Wahab.’ The clapping gets louder and louder. Umm Kulthum sits on a chair in the middle of the stage with her back to the orchestra. She looks at the audience from behind her black sunglasses in a conservative yet elegant dress, holding a white handkerchief. Today, when watching recorded concerts of Umm Kulthum, which are continuously re-aired on certain TV channels in the Arabic-speaking world, the excitement is palpable. The dynamic atmosphere of the concert transmitted to contemporary recipients contradicts this repeated image of Umm Kulthum and her orchestra on stage, which remains the same, from concert to concert – static as if a still photograph.

By 1970, Umm Kulthum’s orchestra had already been electrified, adopting the modern changes that were happening in Oriental music. However, she kept her own style, refusing the fast pace of hip Arabic pop songs of the era. During the concert at the Theatre Qasr El Nil, she debuted a new song of one hour and forty minutes. It kicks off with an unusual guitar solo by Omar Khorshid, part of a thirteen-minute-long intro, before Umm Kulthum gets out of her chair to begin singing.

The recurrent pattern of the intro, which spreads throughout the whole song afterwards, plays an important role in establishing a state of trance or tarab. The static aura and overwhelming presence of Umm Kulthum – the diva of all divas – combined with this dynamism creates a transcendental atmosphere. Though this is the first time they hear the song, the audience collectively reacts, simultaneously calling out, undulating, cheering and clapping. Umm Kulthum’s vocals lead their elation to grow stronger and stronger; the collective trance state is reached at multiple points, as if the audience is orgasming over and over again – despite the absence of any obvious sexual connotations.

Mounira Al Mahdeya was better known under her stage name of ‘The Sultana of Tarab’ or ‘The Sultana.’ The Egyptian singer enjoyed vast fame and popularity during the 1920s.

Nº7 •

Promenade of the Spirits

Performing under the stage name Mounira Al Mahdeya, Zakia Hassan Mansour was born in 1885 and first started singing in the cafés of Cairo, traditionally a male public space, in 1905. Her popularity as a singer grew, earning her the nickname ‘The Sultana of Tarab’ and she soon opened her own café, Nizhat Al Noufouss (Promenade of the Spirits), which became a meeting point for the intellectuals, journalists and politicians of the day.

‘After Dark,’ from The Sultana of Tarab’s repertoire, is one of the earliest Arabic songs with obvious sexual connotations. The music was written by Mohammad Al Qasabji, the famous Egyptian composer and oudist:

Laughter and happiness

get sweeter

Do you remember the

valley of the moon?

You get bothered

without a reason

Forget what happened

and come sleep over

I’m waiting for you Tuesday after dark

You’ll find everything ready

With my hand leading

the electricity

I’ll sit with you the way

you like me to be

Without anyone being there but us

And without too much shyness

But please don’t trick me

while we are in the heat of gayness

And you spread your hand

and laughter gets stronger

I know you for sure

Your hand likes to play around

While these suggestive words would have been shocking in many contexts within conservative communities in the Arab world at the time, cafés, cabarets and nightclubs offered an environment that accepted boundary-pushing acts of entertainment. As havens for members of high society, these spaces formed the roots of the Egyptian arts scene, where many singers, dancers and actors launched their careers. Farid Al Atrache, one of the most important modern music figures of the Arab world, nicknamed ‘the musician of all eras,’ first performed in Badia Masabni’s cabaret. Underground clubs and cafés were the pulse of cultural life, offering solid ground for progressives to express themselves freely, sometimes in the form of decadence, at other times, progress. Within this atmosphere of free experimentation lies the essence of modern culture and its subcultures.