Born in Valladolid, Spain and now living and working in London, artist Saelia Aparicio understands bodies – their leakiness, unruliness and sensitivity. Her sculptural cosmos is populated by hybrid creatures that cross the divisions between different species. Genderless muscular nudes sprout plants from various body parts, fish are plastic parts of flesh and sex toys gape lasciviously from within sculptural assemblages. Her masterful handling of found objects and materials such as latex, glass, kinetic elements and ceramics create complex forms that interconnect across the exhibition space, spinning speculative worlds in which to piece together various commentaries on commodity culture and environmental degradation. Importantly, her work reverberates with a sense of humour that is physical and sensual, balancing the darkness of the contemporary issues that she comments on. Referencing old hybrid forms – from Ancient Egypt to pre-Columbian Meso-America – Saelia exploits the hybridity of her figures to unseat stable categorisations of male and female, animal and human, plant and personhood, in a way that is both amusing and socially liberating.

Natasha Hoare: How different do you find British culture? Does your use of the absurd, abject and erotic speak differently to how it does in Spain?

Saelia Aparicio: We have things in common because we are both European cultures, but there are differences. I felt it most when I moved here in terms of the scale of London. London is a megalopolis, and I was used to living between a small town called Valladolid and villages of no more than 100 people. I think the United Kingdom is also more orientated towards money and consumption. Southern Europe is more family-based; family is very important and so is community. But I have been in London for nine years now and it has changed me and the way that I see the world. It’s much more multicultural here and artists around me seem freer. I’ve been able to meet some amazing people. In terms of eroticism and traditions of abjection, the question makes me think of imagery to be found in the National Museum of Sculpture in Valladolid, the mouldings on buildings in the city, and of the Catholic churches there. The expressions of these beautiful sculptures are so intense, to the point that it is hard to discern if it’s pain or pleasure. There is a great sense of humour in Spain, quite absurd and surreal, depending on the region it can be more scatological or dark.

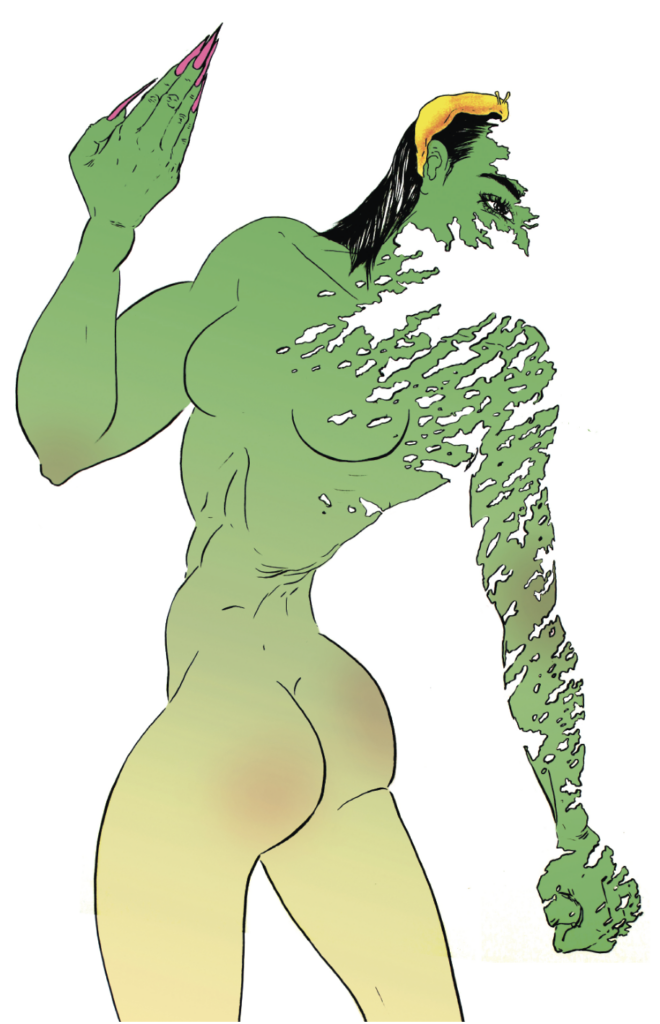

The slug and the lettuce, 2019. Courtesy of the artist

Natasha: You work with many different mediums, but perhaps we can start with your drawings. They show a real influence of manga and anime. What about the form appeals to you so strongly?

Saelia: I love comics and illustration, most particularly the way that they present images and text to create contemporary mythologies. They are able to capture surreal environments, or ideas in ways that are friendly, or harmless. For example, Homunculus (2003–11) by Hideo Yamamoto is a manga series that centres on a homeless guy who gets a trepanation for money. The procedure activates a sixth sense – kind of an extra eye that makes him able to see what people really are: a robot, made of sand or as a walking fish tank with a fish inside. He is able to see a person’s true form.

Natasha: When you were growing up would you read a lot of comic books and get lost in those worlds?

Saelia: I grew up without a TV, so I would read lots of books including comics. My parents didn’t approve of comics so it was a secret world. And I was always drawing. I did make some comics when I was a teenager, but they were quite bad. I also did graffiti; I would make giant squid on the side of railways. I like artistic graffiti. I was part of a crew, but really as a joke because we didn’t take it too seriously. There was a big graffiti culture in Spain in the late 1990s connected to hip-hop being so popular, and there was a thing about painting trains. I only did that once as I am scared of heights and found it all pretty terrifying – but if you could do that you were the crème de la crème in the graffiti hierarchy.

Natasha: How important is humour to your work?

Saelia: The most important thing to me as an artist to be is to be generous, and if I put humour into the work I think I make it more approachable. It can be read at different levels, from a joke to something very unexpected that unfolds. I think humour lightens the darkness of the subject matter. A lot of my art is based on research that I find personally difficult to digest – such as environmental catastrophe – and it can be depressing. So, if I use humour, I think it balances that out.

Natasha: With humour and laughter, you are eliciting a very physical response in the viewer.

Saelia: Yes, because I want the work to appeal to other senses that are not just visual, for example, with tactility or scent: things that can be felt in a different way, that activate other parts of the brain that are linked to memories or are more bodily experiences. I think humour is an extension of that, like another sense: it relaxes you and makes you able to connect with the work.

…The idea of transformation appeals in the way that it trespasses classifications…

Natasha: I was thinking about your work in terms of classical mythology and how that manifests in art, such as the Renaissance paintings of the Metamorphosis stories, especially transformations such as the story of Apollo and Daphne. Do these ideas enter into your imaginary?

Saelia: Yes, I think mythology in general, but also the Jungian idea of the collective unconscious – the notion that we all share particular structures of the unconscious mind. In different cultures, we find the idea of the hybrid – creatures that are powerful and intimidating, either gods or demons. That idea of transformation is particularly Greek, and we can see it in European paganism, or in medieval monsters. Ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia and pre-Columbian Meso-America all have hybrids that are between animals and humans. Think about the sphinx or the Bastet goddess: half-feline, half-human. Or Anubis: half-dog, half-human. Or, for instance, the Mayan Camazotz, a Meso-American bat god, born from the blood and the semen of sacrifices, and the Aztec Tzinancan, a god of death, darkness and nocturnal pollination. I find these figures very interesting and inspiring. Also, the idea of transformation appeals in the way that it trespasses classifications. It’s like a superpower. We are transforming all the time, even when we are digesting something it’s an internal process of transformation. Think of death – a transformational process that is so potent, so separated from us in the contemporary moment – it is something that only happens in hospitals and care homes.

Natasha: Death is the final transformation, right? The beginning of your body breaking down and becoming part of the earth again. The dissolution of you as a form. I’ve been reading a text by the British artist and writer Jamie George entitled Jack Built, which was written for Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art. It talks about how some believe the dead body was the first object; the soul or animus having departed the body becomes an object. That thought is interesting in terms of your being a sculptor who is making bodies all the time. You move from that first moment of the body as an object.

Saelia: I like that idea because it feels very true. I feel like I have a responsibility for creating objects out of certain materials. I’ve recently made a rule to make work that uses pre-existing objects, found or bought online and secondhand. Or materials that can be reabsorbed into the soil. Materials that will evolve and change. This has made me think about the Western obsession with things having to outlive us as an artwork. I don’t think it’s necessary to have to think that way when making work. I’m also very interested in the emotional load of objects that have already been used.

…We get these uncontrolled responses from sexual stimuli. I am particularly fascinated by fetishes. They have no place in my own psychology. I don’t think I have any fetishes, at least not that I am aware of!…

Natasha: Yes, found materials already have a certain charge to them. How does sex and eroticism enter into your practice? You seem to play on the seductive potential of objects – sometimes going so far as to use sex toys directly, otherwise materialising objects that might be bodily organs.

Saelia: Sexual impulse is certainly present in my work. Desiring sex comes from our reptilian brain: one of three emotions that rule this most primitive part of our psyche – mating, pain and danger. We get these uncontrolled responses from sexual stimuli. I am particularly fascinated by fetishes. They have no place in my own psychology. I don’t think I have any fetishes, at least not that I am aware of! So, I find them fascinating. I’m intrigued by how the creation of a fetish breaks the body into separate parts. You don’t have to like the whole person if you are attracted to their fingernails, or to the hairs coming out their nostrils. I find that wonderful. It’s led to my fascination with male masturbators in particular. Sometimes they are like agglutinations of hyper-realistic sexy parts, but omitting those parts that are not attractive, and you end up with really strange results – I’ve seen toys such as a silicone foot, with a realistic vagina in the sole. How would you describe these saucy mash-ups? I’ve also come across one that is shaped like a gherkin with a prolapsed anus, or a hyper-realistic lower half – but just the lower half! – or totally transparent sex dolls. These are all things I find so amazingly strange and beguiling. Who gets turned on by this? I want to apply this logic to my sculptures.

Natasha: I can see that appeal of the fetishised object as something that is generative – of strangeness, of pleasure or new ways of thinking about bodies. Your sculptures are assemblages, made up of isolated and abstracted parts of other things. Does this interest also follow onto an idea and critique of the commodity fetish?

Saelia: I think you can see that in the works. I am critical of commodity and consumption both in the way I use materials and in my ‘identity-constructed portraits,’ which are sculptural figures that appear in my installations. We have too many options. I don’t want to moralise, but I do have ecological concerns. Serge Latouche says that progress is like a fast car without a driver. What do we really need? Are these things really necessary? We need to think about how the comfort of someone comes from the discomfort of someone else. Mining minerals, pollution… there are complex sets of interrelated causes and effects. I try to echo that complexity of interrelating issues in my work. To disorientate the viewer, talking about different things at the same time. I don’t think there is a straightforward solution to anything. I put together elements and ideas so that the viewer can think for themselves, relating things that seem unrelated.

Natasha: The bodies you depict, usually through drawing on paper, walls or textiles are very specific in their gender fluidity, strength and potential to transform and disobey. Can you talk a little about how you’ve come to depict these? Where do they come from in your thinking?

Saelia: I was bringing in the idea of the ‘two-spirited’ and gender fluidity that comes from Indigenous North American culture. People could have more than one gender, that was normal in their society. Again, it comes to the notion of hybridity; being-half, plant-half human, with no clear gender. It makes my figures more powerful, and the way I use body language and movement gives them a vulnerability at the same time. This started in 2017 with some sculptures I made for Peaks & Troughs at TURF Projects in London that were cultural stereotypes, in particular the Eco-Warrior, which was a figure with a plastic plant growing from its head, and the other is Anatomy of Pleasure, which is made from plastic materials. I was thinking of the cultural specificity of each. To me, they didn’t have a gender. I thought of Anatomy of Pleasure as a woman because she has heels, long hair and bright colours, but I also thought about her as a drag queen. Through the process of making the sculpture I realised that we automatically assign gender to things.

Natasha: Your work is intensely aesthetic and pleasurable to look at, and yet has a political edge in terms of its environmentalism and engagement with gentrification. How do these two streams manifest?

Saelia: In one body of work, I respond to the Carpenters Estate in Newham, Stratford, made up of derelict blocks of around 700 flats that have been almost empty for years. The council wants to knock them down to make room for new urban developments. There are twelve flats still occupied in one, two in another and sixteen in another. The residents refuse to leave their homes, which prevents the development from going ahead. Stratford is a fascinating area because it has older blocks like this, which contrast highly with the shiny new Westfield shopping mall. The old local shopping mall, which has more affordable shops like Aldi, is a 1960s design that is open and accessible 24 hours a day. At night hundreds of homeless people go and sleep there just opposite these near-empty tower blocks. I looked at this predicament in my 2015 graduation show at the Royal College of Art in London. I made a tower block out of stained glass, with see-through neighbours in the windows; delicate bubbles in a gigantic, metal structure. Then later I made an animation series called Greenshoots where plants grow out of the buildings, which came from looking at the neglect of the structures and the plants growing on their abandoned balconies. I wanted to thank Newham for a potential new species that is able to develop in these spaces.

Natasha: Plants seem to occupy different statuses – becoming part of human forms in a way that is both threatening and seductive. Do you use them to emphasise certain aspects of human life?

Saelia: My research around nature has become quite dispersed over the years. In the Greenshoots series, figures germinate with the plants that were growing in the balconies or through the empty floors. They express the resilience of these neighbours to stay in their block, which must be isolating and hurtful. I have since been looking at plants that were introduced through gardening as exotic species but that have become ‘invasive.’ We look at trees, flowers and shoots as immobile and intellectually inferior living beings. If a rare plant can live in a botanical garden and is ‘the only one in Europe,’ then it is admired, but it is really the human ego – a very anthropogenic take – that is speaking there. If a plant is brought from another geographical location and thrives too much, we condemn it and call it invasive; we apply human morals to other living beings. I wanted to work with more of these plants that have adapted and have become part of our urban landscape.

Natasha: Speaking of an ‘invasive’ species – one series takes Japanese knotweed as its focus.

Saelia: Yes, that was for an exhibition in Madrid in 2019 at The RYDER Projects titled Madrid Planta, Alzado, Raiz. The exhibition was constructed along the lines of a story in which an empty house is missing the warmth of the human bodies that had inhabited her. Now Ivy, Buddleia and Japanese Knotweed are growing on and inside her, destroying her structure, and creeping through her facade. The plants tell the house not to miss humans, that they are not here to destroy – it’s just the way they live. They are asking us not to apply human morals to them and their growth. Humans first created the house then abandoned her… they also planted the plants, admired them for their beauty, but then condemned their capacity to live, as having adapted ‘too well’. Knotweed, in particular, is fascinating, there is a whole industry that has evolved around it to get rid of it. It’s a contemporary housing monster. I’m interested in the flux of plants, and how the terms we apply to them revert back to human populations. For instance, invasive weeds have become a metaphor for immigration, especially since Brexit. I’m thinking about how the West uses the resources of different parts of the world, but we don’t expect people from those locations to come here and supposedly become an ‘eyesore’ or a ‘nuisance’.

Natasha: Each material you utilise seems to have a specific semantic sense. What materials are you currently most drawn to? How do they map across your various collaborations with other makers?

Saelia: I work in an interdisciplinary way with artists who use many different mediums – sound, video, fashion design. I’ve been looking at the computer software Adobe as well as working with pottery, soap and weeds.

These materials are new to me. Getting to grips with them opens new worlds of possibilities. Now I am taking baby steps in ceramics, which I learned in Oaxaca with a very skilled maestro named Francisco, and also with Julia, a ceramicist from Las mujeres del barro rojo in San Marcos de Tlapazola, a village where a community of women ceramicists collaborate while most of the men work in the United States. I was there in October and they have been a big influence.

They model things in clay, applying an engobe of special red clay that is collected in the mountains. This process clearly shows the influence of pre-Columbian culture. They are bilingual and speak in Spanish and Zapotec. I went to visit both Julia and Francisco and their families during the Day of the Dead. I took part in a ceremony that explored how they would imagine those lost ancestral traditions to be. It was really eye-opening to be in Mexico and witness the relationship they have to death and dying. It’s so different from the Western approach. People were at the cemetery, but no one was crying.

It felt celebratory of life and more accepting of death. Death is not hidden; it is acknowledged.

Natasha: Many of your exhibitions include works that are drawn directly onto the wall. Is there a sense of loss when they are painted over?

Saelia: No, not at all. Disappearance is part of the work. I don’t think everything needs to outlive us. It makes me think about materials in that way. When we are talking about commodities, we speak of them in terms of the fantasy of Western preservation. Things are supposed to live forever when actually they are in a permanent state of change.

Natasha: In Atrophic Chain you present your drawings on the wall painted with UV paint and the rooms are darkened. Is that immersive aspect of your work important to the way it’s shown? What are you trying to create for the viewer through that mechanism?

Saelia: That project was a collaboration with my sister. We were inspired by the BBC documentary series The Blue Planet narrated by David Attenborough. We gave the viewers little UV torches to focus on the drawings so that they would feel like deep sea fish. We wanted an active viewer who could discover things playfully.

When I make my installations I pay attention to things such as the light, the floor, the scale of the room, the particular environment. For the show at the Tetley gallery in Leeds, I made a lot of stools. That changed the way that visitors reacted to my work, although some people were still reluctant to sit down as they saw the stools as ‘artworks’. Sometimes, I play around with chemicals, thinking about how very strong scents can influence the way we feel about things. In Prosthetics for Invertebrates, I tried to conjure the smell of cleaning products, like artificial lemon, so it gave a very strong sense of sanitation – it made the space feel very septic. This also functioned as a reminder of how substances like bleach or plastic bottles have a negative impact on the environment.

Natasha: You have said that there is a lot of darkness in your work, which is interesting. I think because of the unexpected juxtapositions with found objects there is a lightness – there’s something quite amusing there too.

Saelia: Yes, I think there is. There is a lot of darkness in the world, so it comes through. But the world is not only darkness; it is also light and beautiful. In Atrophic Chain the sea animals are hybrids with plastic debris. These scientists were surprised when looking in the Mariana Trench that there was plastic there, and microplastics. Lots of ecosystems contain plastics and pesticides and we have no idea what effect these are going to have.

Courtesy of The RYDER Projects, London and Madrid. Photo: Pablo Brecha

Natasha: I think a lot of Donna J. Haraway, especially her 2016 book Staying with the Trouble, talks about speculative forms of storytelling that highlight the entanglement of different forms of life. Has she been influential on you?

Saelia: People share fragments of her work with me a lot, and I’ve read When Species Meet (2007), The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness (2003), A Cyborg Manifesto (1985) and other texts, so certainly she’s an influence.

I also like science fiction; I am thinking now of Jeff VanderMeer from the New School and Octavia Butler. Butler’s fiction took me outside of the small town in Spain that I come from.

Natasha: You’ve described your work as providing speculative worlds that people can step into. I think your work actually operates in the same way as sci-fi?

Saelia: Yes, certainty. I find it inspiring that the genre offers a means of seeing alternative futures that could take place in the world we live in. This kind of storytelling can take you outside of your context and spin incredible dystopian and utopian narratives. New, hypothetical ways of looking really excite me.