Turner-Prize nominated artist James Richards uses a particular phrase to describe his fascination with the films of fellow artist Steve Reinke; that through his work you get a sense that Reinke is ‘living with images’. This encyclopaedic and magpie relationship to film, its histories and materiality, is tangible when viewing Richards’ own artworks.

His films and recent sound works are sensual, affective, and deeply invested in the formal potentials of their medium. Lovingly crafted, and stitched together from fragments of found footage and his own self-shot material, the structural conditions and fruitful limitations of filmmaking are deftly and subtly explored, without sacrificing an intensity and dream-like quality. Collaged forms reoccur; water and eyes particularly, emphasising perceptual processes and the line between conscious and subconscious realms. Images are flipped, inverted, abstracted and translated through a process that is rich in formal experimentation and powerful in its de-familiarization of both the banal and sublime. Erotic and sensual imagery are important elements in many of Richards’ works. The manipulation of the viewer through the erotic, in partnership with careful editing and sound, is a key tool to conversely both create distance and lure into an intimacy with the work. As ever, in his deconstructive modus, the erotic image is never straightforward. At one turn its thin materiality as an image in a magazine or book is exploited, and by another richly and sensually indulged in to break a previously established rhythm and feel.

James Richards, Courtesy: Interview Magazine Photo; Sebastian Kim

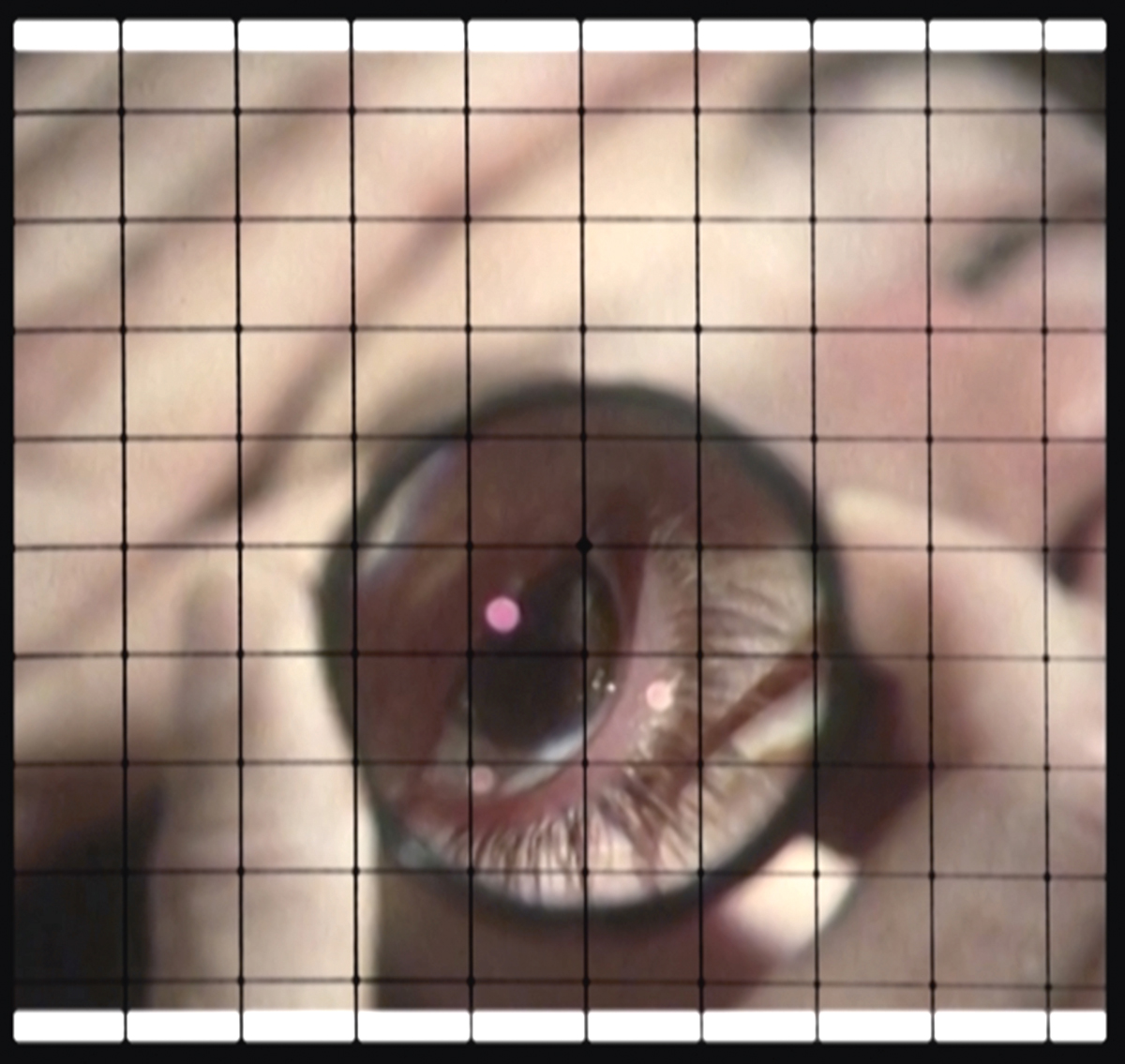

Natasha Hoare: I was watching an early film of yours, Practice Theory (2006). There is a moment when a voice says: ‘De-construction and exposition of mediation towards a certain purity.’ The camera then reveals its own lens eye when it comes close to a reflective DVD casing with an image of teenage boys touching themselves. It’s an elegant simultaneous action of eroticism and deconstruction. Do you see this as a statement of intent regarding your work?

James Richards: I think the idea of shifting between something objective and something more basic and impulsive is probably one of the main emotional moves in my work. It happens in the compositions themselves and also in the way I install shows; the playing off of an objective structure in the work that slips up and allows a much more emotional, beautiful or sensual experience.

Practice Theory is an early work of mine that I made at college. Looking back I see it contains many of the elements that come back in later projects. There is the relationship to structural materialist work, and to the history of that, and the allowing of the exposure of the medium or format to also become content and thus meaningful in some way. Also, in the shot of a desk full of scraps and fragments, my process is shown as this sifting through material at close proximity, collaging the provisional and lo-fi as well as still images. It’s a crude way of bringing an existing image into a video work, one that allows the awkward elements of time – the tremble of the camcorder and limits of its auto focus – to become part of the image. The work tries to speak of the technical contingencies of image making, and to express the predatory relationship between myself, the camera and the image.

The audio for this early piece is from a video found online. It was just a very brief lo-fi thing somebody made about the Roland 303 synthesizer, which was responsible for the development of acid house music. The essay was obviously written in a cut-and-paste manner, containing lots of bits of essays on culture, art, technology and communication. Then, a text-to-voice software took over the narrating part. I chose a particularly pretentious and slightly muddled passage for quoting more as an example of a certain kind of reading and talking. It’s very malleable in the sense that you can stick anything in front of this text and it seems as if it tackles the object. I set up this found voice with a series of images so the video starts behaving as if it’s going to tell you something. Then there’s a rupture, the camera gets stuck on an image on the back of a DVD of boys holding their crotches. The camera tries to get closer to them, to consume them in some way. This idea of the camera as an entity with a physical hunger or desire interests me. Rather than just seeing or recording there are these moments where it feels like the camera’s lens is trying to touch or take in an existing image. So the screen or projection surface of the work is experiencing a compressing process, from acting as a window to functioning itself as a surface that reproduces the image. Thus the film speaks to a movement from objectivity to an embodied state of ‘feeling’ images. This transition in a way of viewing is something that I have continued to work with, but in Practice Theory it is shown explicitly when the objective agenda is sidetracked by libido or desire.

Rosebud, 2013, video. Installation view. Courtesy: James Richards and Rodeo, London

Natasha: The film Rosebud (2013) centres on erotic images, and in it you picture the Japanese practice of scratching out explicit imagery from books. I was wondering if there seems to be a dual interest here in the flatness of the image, which is revealed by the scratching away of this very shallow layer, and also the spectre of the erotic that the images help to contain even though they’ve been scratched out.

James: Yes absolutely. The work focuses on a number of fine layers: of printer ink, of human skin, the meniscus of water, and equates them all, but according to a sensual poetic order, rather than something analytical.

Rosebud is an evasion of the analytical, it’s more to do with projection or anticipation, how one projects into images and what’s felt when doing so. When the heart of an image is removed your brain gets activated. Seeing the space where the genitals were, all we can do is think of his genitals, and of the caress of the person removing them with sandpaper and the flat, high-end phonebook printed surface being the site for this futile masturbatory rub.

Natasha: There’s a very sensual passage in which elderflowers are drawn over parts of a body. I was wondering whether those sequences directly engage with queer histories of representation in film, and in terms of use of the Mapplethorpe image, if that’s articulating an engagement with him as an artist and photographer?

James: I like Mapplethorpe’s work, but I don’t feel my work deals with this head on. Certainly not with the political or racial issues that it brings up. In Rosebud the important thing is the sense of the canonical. The iconic and circulated image, which then allows more attention to be put on what the image has been subjected to and what it’s placed alongside. I liked the idea of making something with a recognizable, iconic canon rather than the perhaps more obscure artefacts and artworks that appear in my work usually. The title Rosebud is lifted from his oeuvre.

There’s a work in his X Portfolio (1978), which contains studies and portraits taken of men he met in New York and San Francisco’s BDSM scenes. One image called Rosebud shows a man’s anus that’s been fisted and become fleshy and enlarged in a way that recalls a closed rosebud – it was the slang at the time. Rosebud also alludes to the snow shaker in the opening sequence of Citizen Kane. It felt necessary to evoke Citizen Kane in the title as all those black and white swirling water shots have some of the feel of the snow shaker sequence

at the beginning. The film moves between very specific recognizable documents of photographs, and then you have these reveries, distractions

and immersions.

By its very nature, sound works more on the body than image…

Natasha: Your work, in its visual intensity and sonic qualities, is heavily affective. Especially in Crumb Mahogany (2016), an audio piece that suffuses the viewer in waves of sound, where you move away from images altogether. Is that bodily affect of your work on the viewer important to you?

James: By its very nature, sound works more on the body than image. Somehow one has a less objective relationship to audio. It affects you and it’s harder to shut out. Literally sound enters before you start trying to analyse it, whereas the image is ‘read’ and can be turned away from.

In my view, affect is an important place to start making art and it’s the impetus for moving in a specific direction. My question is always ‘what is it doing to my body?’ I like to find moments that feel spot on, or spot-off, and to build up a composition from these different combinations, particularly with the music pieces that I’ve been experimenting with recently. They are composed on specific equipment and through speakers that are circled around me in the studio or exhibition space. I use trial and error to build up configurations of sounds that really work on you. There are very musical aspects to the process; trying out differences of chords to find a hook. That comes when something is really working in a physical or emotional way to push and pull you through a range of different associations. I’m doing all this against my own body, so my logic is a physical one.

There is a kind of subculture in relation to drugs and sex in London at the moment. Certain intoxicants, that break down inhibitions and arouse, are making change in ways by which it’s possible to arrange to meet and have sex…

Natasha: Yes, the use of sound is an almost architectural one in that work, quite a different way from working from the screen where viewers are receiving images. I was also interested in this repeated use of water in your work. In Not Blacking Out, Just Turning the Lights Off, there’s a very strong sense in which we’re being drawn into a different dimension, and it does feel very sub-aqueous or that something is thickening. When you’re playing with the meniscus of the water, the lens is popping out and back in, and there’s a sense in which the surface of the water is almost becoming a lens. Are you trying to build this space of poetic alterity for the viewer, a lateral filmic space?

James: Liquidity in Not Blacking Out is about trying to get inside the body – moving towards interiority, and in my opinion very much about liminal points between inside and outside. The work is about intoxication, going under, blacking out, about getting closer and leaving oneself. Presumably this comes from some sort of crisis or physical anxiety around inside and outside and about thresholds between people and between bodies. Quite a neurotic film if you ask me. There is a kind of subculture or practice in relation to drugs and sex in London at the moment. Certain intoxicants, that break down inhibitions and arouse, are making change in ways by which it’s possible to arrange to meet and have sex, with apps such as Grindr, as well as the development of prescription drugs like Prep and Viagra allowing for a culture of drug-orientated sex parties to form. ‘Chemsex’ is the rather negative term that’s being used. When making Not Blacking Out, Just Turning the Lights Off I was trying to grapple with some of the feelings around this kind of sex. There’s a lot of work that tries to speak of cruising or casual sex through reproducing objects or spaces connected to it, but for me it felt more interesting to try and really go into the psychological spaces of intoxication and intimacy, of what it is to feel boundaries broken down, but also to lose oneself, to get out of oneself. That’s where this liminal woozy feeling comes in – this movement between subject and object, between inside and outside, the self

and other.

Radio at Night, still, digital video, sound, 8 min., 2015 Courtesy: James Richards and Rodeo, London

Natasha: In To Replace a Minute’s Silence with a Minute’s Applause (2015), you were responding to a Francis Bacon portrait from the collection the VOC in Moscow. When I was watching Radio at Night, there is a hanging animal body in the split scene section that creates an interesting visual connection between you and Bacon. Is his relationship to the human body influential on you?

James: Yes, in an embedded way, not in a direct way. This beautiful visceral mix of sex and flesh; I really enjoy the work – the viciousness of it. The meat motif in the recent works like Radio at Night (2015) and Rushes Minotaur (2016) is coming through his work. With Bacon there’s a shifting between inside and outside, the clinical and the subject, which is something that my work also oscillates around.

Natasha: In Radio at Night there are beautiful passages taken from a movie showing the Venice carnival at Venice. Does this idea of costume and performance point to the con-structedness of identity and sexuality?

James: The film is from the late eighties and nineties and was made by a French erotic production company, who make just straight-up porn now. Those sections I used are from parts of that film that were between more pornographic sections. It was when porn films were still made for the cinema rather than clips, so there tended to be more narrative content and more atmospheric sequences in the films that weren’t overtly erotic. It is a very decadent film and reminded me of Derek Jarman, in that behind its decadence it just consists of cardboard which is covered in glitter and glue. In fact the piece was commissioned by the Walker Arts Center in Indianapolis to be in dialogue with a Derek Jarman film.

Lots of people have commented that this section looks like the New Romantics from the eighties, but it would be too easy to just be nostalgic. I used it more because it’s oddly ghostly and sad. And there’s something about the camera projecting a specific kind of light on the figures.

The works are first and foremost formal exercises. With regards to the politics of representation or queer histories, I don’t set out to build them in, but they’re there because they are a part of the texture of looking and living with images, and obviously my life and what I’m looking at and living with, is in some ways specific to what I am and what I do. So there’s a lot of things going on in the work, but it’s not necessarily placed there in a discursive way or because I’m active in any discourses specifically.

Crossing, 2016, video by Leslie Thornton and James Richards, installation view

Natasha: Collaboration and curating are part of your practice also. Recently you worked directly with Leslie Thornton and have also collaborated with Steve Reinke to make works. Is this process of collaboration important to you as an homage to the people who might have influenced you? And is it a useful methodology for furthering new techniques or rubbing off against each other?

James: Making work in the studio is a solitary affair. So if a situation comes up to work with another artist I admire I’m always interested to see what happens. Collaborating with other artists, or organizing exhibitions and screenings, and showing their theory are both ways to engage and further a relationship with work that is inspiring. Steve Reinke had a big influence on me while I was a student. I first saw his work at the LUX in London. It felt like someone living with images, detached and funny and genuinely odd. He relates to images with a very singular sensibility. Moments of creepy fascination cut to witty, kitschy graphics or declarative lines of text. This feeling of a tough collage, of the compilation structure in his work, has also been very influential on my work, as is the mixture of the self-shot and found, of abstract computer-generated sketches and absolute unaltered readymade.

For me, collaborations are mostly about interaction and taking stock of one’s own interests, to have these projects where it’s not all about your own thing. It’s no coincidence that the longest works I’ve made are those pieces that have come out of collaboration. When working with another person you never come up against that kind of inertia of working alone. Instead there is this explosive process where two languages are meeting and so much is overlapping and being found out in such a short space of time that a lot of great moments happen. I like this space of testing out another’s vocabulary. Collaborating with Steve Reinke or Leslie Thornton always means trying to ape or mimic qualities in the others’ work that you like. It’s like making conversation and picking subjects that you think someone likes talking about. So the collaboration starts with a kind of mirroring and mimicking and then, as the passages build up and it starts to take shape, the work really becomes its own beast, with its own style and logic and not just a sum of the two authors’ work.

Natasha: As you mentioned earlier, the work with Steve is very explicitly erotic, and by turns funny and dark. What were both of your approaches to selecting and editing together materials for this piece?

James: The work with Steve was made remotely, with us in separate continents – him in Chicago and me in London. We used the mail as Dropbox wasn’t around then and sent each other packages of files. I loved the anticipation of sending material and then it taking about two weeks for Steve to rework it, add things, cut new things in, change the sound of something, with me in the meantime doing the same with what he had sent.

These alternating packages of growing changing fragments eventually merged together and we assembled Disambiguation (2009). It’s a spiky, grubby video, kind of the most punk rock thing that I have worked on.

Yes, it’s the most explicit work I’ve been involved in making, drawing a lot on webcam and role-play footage, medial material and creepy B-movies. One strand in the work is the fetishization of unprotected sex in certain areas of gay culture.

Natasha: It’s interesting in your work as well how certain images or sequences of film reappear. Do you see all the works operating together as a chorus? Or are you interested in creating new juxtapositions with existing footage to create new effects?

James: I’ve always liked the plasticity of digital video. The casualness and feeling of immediacy that it can have. Somehow the permanence and solidity of cinema editing never really interested me as a model for making work; I was instead drawn to finding a way of structuring the moving image that was more material, improvised and scrappy, that spoke of a process of sifting through, of living with moving images – improvising along the way; adjusting things for a particular exhibition or screening contexts, and somehow this working clips, or cannibalizing parts of existing work in new compositions, feels natural.

Sometimes you don’t feel like you’ve used something fully or correctly. Then it resurfaces in another piece, reworked or in a different installation setting or with different sound added. Embedded in that new place it feels different and pertinent. Perhaps on a more knowing level I’ve always been interested in this déjà-vu quality to a practice. Structurally in the work, I play with repetitions. It’s quite a musical thing as well, referring to the chorus, verse and bridge.

In my recent exhibitions I’ve been extending an improvisational approach. For some shows I’ll work directly in the space, testing what works for the acoustic and architectural proportions – literally feeling out the work spatially. In doing so the works often become quite minimal, far simpler than the multilayered single channel videos I make. In being more minimal and improvisational I find myself returning to images I’ve worked with in the past, but feeling them, honing in on them, stretching them out, into these simpler more spatial gestures.

Natasha: I have a final and personal question: what is the first moving image you can remember encountering?

James: I really remember my brother and my dad were watching Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life. It has a scene where a restaurant critic eats so much he explodes.

They had obviously made a kind of rib cage that bursts open, and I remember being horrified and running to the bathroom crying!