Eddie Peake’s artworks marshal affect to inseminate the hallowed gallery space with a sweaty slick of bodies rendered under the fluorescent light of the nightclub. Driven by jungle music, his universe is populated by figures moving to a shared beat, swapping partners and gender assignations, from digital to real, trading long-held secrets whilst dripping in glitter and Day-Glo. As such, Peake’s immersive environments, paintings and choreographed performances variously draw on dominant musical and aesthetic forms of nineties youth culture, accented through the erotic charge of the naked human body, to stage confrontational encounters within the museum.

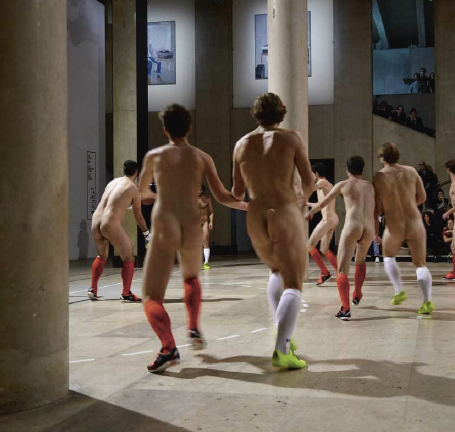

Previous works have included Touch (2012), a naked five-a-side football match at the Royal Academy Schools, in which the absurdity of the action was supplanted by both the seriousness of the sport being undertaken and the inherent homoeroticism of close-contact sports. Amidst A Sea Of Flailing High Heels And Cooking Utensils (2012) was a two-part work across both Tate Tanks and the Chisenhale Gallery, in which nude and scantily clad dancers simulated sexual encounters, positioning the viewer as a willing voyeur, the gaze submitting to, and transmitting, libidinal desires.

When we met, his show Forever Loop had just opened at the Barbican, London. In person he is softly spoken and eager to connect. Wearing head-to-toe graphic prints he comes across as a gleeful manipulator of the demarcation between the role of artist, DJ, performer, and indeed ‘rude boy’, a slipperiness of identity and – that very British preoccupation – class, which also comes across in his work. Peake is also a prolific actor in a network of young London-based artists who have traversed an austerity economy and severe arts budget cuts to craft their own scene – be it in visual arts or music – and whose work celebrates the generative contamination between the two. The brutalist concrete architecture of the Barbican framed both our conversation and his installation, which variously features semi-naked roller skaters, scaffold scenography, gilded objects, freestanding sculptures, and screened films of both previous performances and digital works. Peake evinced a characteristic frankness about his past, citing depression and a brief stay in a mental health institution as a stimulus for the text-based pieces in the exhibition; here, trapped in a Forever Loop, the come-down is as palpable as the ecstasy.

Subconsciously I realized that the best thing was not to try to do something that other people are doing, but to create your own language and scene.

Natasha Hoare: Your work is heavily informed by your background as a Londoner, growing up listening to jungle and drum and bass, and being an active part of this particular music scene. How did this affect the formation of both your identity and your practice?

Eddie Peake: Well, to speak very specifically about jungle; one of the variety of ways in which I first encountered this music was through a pirate radio station called Kool FM. It was set up in Clapton, East London in 1991, and has various studios around the city. I’m from Finsbury Park close by, so it was a local thing for me. Listening to Kool from a fairly young age, I was brought up in an environment where music was a constant. Jungle was the first ‘sonic aesthetic’ that I was exposed to. That sounds terribly pretentious, but the reason I use that phrase is because there is such a particular visual world that comes along with it.

Touch, 2012 at London’s Royal Academy of Arts

Natasha: It’s a very particular cultural moment in the UK, and London, when drum and bass and jungle were hitting the clubs. Your work straddles these genres and the art world both in its use of the music, your association with Kool FM, and your own club night.

Eddie: Yeah, my club night is called Anal House Meltdown, which I run together with some artist friends: Prem Sahib and George Henry Longley. Usually, we play at one another’s exhibition after-parties; as such we recently hosted a session after George’s show in Glasgow. It was a typical Anal House Meltdown party, with lots of guys dressed like women, lots of penises, everyone taking poppers. The crowd at these parties is made up of about seventy or eighty percent gay guys. It finishes at whatever time, and then people go on and take more drugs elsewhere. The following morning I travelled back to London for a visit to the Kool FM studios to meet the guys there and to see it for the first time. I’m pretty friendly with them all now. It was an amazing experience to be there, having listened to them for maybe twenty years.

Natasha: For your graduation show at the Royal Academy you invited Kool FM into the gallery spaces in a makeshift studio, where they performed live on air for eight hours a day. It was an almost surreal experience to walk through these historic spaces that have hosted an art school for hundreds of years, and encounter this sweaty, charged, pulsing installation. How did the Kool FM crew respond to performing in this context?

Eddie: They really appreciated it as they have spent much of their time as an organization being told they are illegal and illegitimate by the authorities and establishment. Then, somebody who re-presents establishment and authority is pointing them out, saying, ‘no, what you do has cultural relevance. It’s important and we’ve been inspired by you and we recognize the importance of what you’re doing. Come and do it in our institution.’

In my view that was a significant moment for Kool FM and from that moment on we’ve maintained a good friendship.

Natasha: There’s a real potency in your work in its breaking down of barriers between what is considered ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture. Contemporary art is often regarded as elitist in the sense that it speaks a language that is self-referential and complex, which can be alienating to audiences. In your work you apply your own popular cultural references to create a more universal and somehow visceral visual language.

Eddie: Well, when I was a kid I dreamed of being a DJ or playing in a band. Once a teenager I did both of those things and bought stacks of jungle and drum and bass records. At a certain point, I lost interest; subconsciously I realized that the best thing was not to try to do something that other people are doing, but to create your own language and scene. At the age of eighteen, I was playing in a band and putting on nights with my brother and our friends. Almost by accident, I made some paintings in school that I thought were good. Interestingly that was the time when I was suffering from depression and about to drop out of exams. In one fell swoop, I fell out of my entire circle of friends and at that exact sort of crisis these paintings came about, rendered in something resembling my own voice, and my own language, as opposed to buying jungle and drum and bass records, and spending time trying to be part of an already existing scene. Speaking of my practice today, I want my work to be in the world, not just in the art world. I feel like the art world is very comfortably harmonized and closeted away.

Natasha: Having started in painting at this early age, your work at the Royal Academy of Arts, and later as part of Performa and at Tate Tanks, is performance orientated. Many of your works use nudity, imposed onto mundane situations such as a football game, or across choreographed dances where the naked form and its gestures appeal to an art historical legacy of sculpture and painting. How did your use of the body in your work come about?

Eddie: My work had always been per-formative, if not outright performance. As a child I always liked drama and dance. Once I was a teenager, a horrible insecurity that inevitably accompanies that time of life really did get the better of me, and as a result suppressed that extrovert performer tendency. On leaving school and going to art school, there was this eagerness to tap into that once more and bring it to the fore. So, I started going to dance classes. Painting was indeed the reason that I went to art school, but I quickly became frustrated with the frame as a delineated boundary. You can play around with that and expand your painting, but ultimately you are dealing with a flat surface that is hung on the wall, which can be limiting. One of the things I did to break with this was to shoot my own body, with the help of a friend of mine. We shot me naked and masturbating, being a type of character – a parodied version of my own self. One of those images is still to this day my website picture. When seeing those pictures, I had another epiphany moment in a way that I can’t articulate properly. What are these images? Who do they belong to? What do they mean? What sexuality is happening in them? Who am I in them? All these thoughts and questions exploded in what I thought my work was, what I thought was me. It was a key moment for me.

Natasha: It’s a brave moment in your work, sharing this extremely self-revealing imagery, despite the conceit of a character or alternative persona. Has it been a cathartic moment in terms of display of your body and sexuality?

Eddie: Yes, it really was. The sexuality aspect was accidental. I didn’t think to myself – or there was no such plans as – ‘I want to make a set of images that are sexually weird.’ It was rather the desire to make some images that were difficult to place. That was something I thought came up in my thinking and ongoing practice as a result of this body of work, both in terms of the gender and sexuality. At the time I’d been thinking that I wanted to start making work with my body, or naked bodies, in a way that a lot of young artists do. It scared me why I wanted to do that and I tried to find a justification. In hindsight, I remember when I saw those images it was one of those moments of realizing that you don’t need a reason to do anything, you just do it and then figure out why.

…Essentially, it is a set of imagery that can be enjoyed and an aesthetic that one doesn’t need to feel shame or guilt about enjoying…

Natasha: So, this attraction to working with the body, nudity, and reasonably hardcore imagery is merely instinctive and avoids any attempt at pre-figuration. How does it feel then to move into an arena where you are directing other bodies?

Eddie: I remember the specific moment that this shift occurred. It was after taking those photographs that I started making more performance work. At this stage I was always performing in these pieces, and by and large the only invitations I got for shows were for performance works. So there’s a whole set of reasons why that was the case, some of which I found quite interesting. A lot of this performance focus related to a swing towards a right-wing politics that has pervaded this country for the last twenty years. This political climate has left artists with very few resources. Doing performance was a ‘backs against the wall’ thing that we could do. We couldn’t afford to rent a studio, or buy expensive materials. What I do have is a body to use freely. Having said that, in doing lots of performances, I didn’t know why exactly I was doing them. Again, there was a preoccupation by the question, ‘why do I need to do this?’ instead of letting it flow. In 2008, I went to Rome and upon my return I realized the wish to get rid of any shred of self-conscious irony in my performances. I don’t want to second-guess anyone’s potential response. One of the main things that resulted from this was my decision to step out of the work myself; to be able to see it, I started working with performers in a more directorial way. Choreography became more and more a part of it despite me being quite particular about saying I’m not a choreographer – I am merely an artist working with performance that requires this aspect.

The Forever Loop, 2015 Photo: Justin Pieperger Courtesy: Eddie Peake and Barbican Art Gallery, London

Natasha: So, around 2010, you moved outwards, to objectively see the work and direct other performers in ensemble pieces. Despite this move away from using your own body as image, eroticism and sensuality remain core aspects of these performances.

Eddie: Yes, to a varying degree of visibility. In some of the performances, that aspect is more of an incidental by-product than something I consciously tried to have the work embody. In other works, this has been at the forefront of my mind and I’ve wanted to portray erotic sexuality.

…We couldn’t afford to rent a studio, or buy expensive materials. What I do have is a body to use freely…

Natasha: Why is it important for you to stage these displays of eroticism in the public space of the gallery? These modes are usually private, intimate and withheld. What do you try to achieve with projecting them through bodies in a public space?

Eddie: It is a serious part of the work. It’s quite easy for the work to be co-opted by interpretations of it that are not necessarily intended. Like weird perverts coming to the show and spending three hours, not because they’re interested in art, just because they want to perv on these beautiful people prancing around naked. The other response is when people say something to the effect that I am trying to do something to provoke. Essentially, it is a set of imagery that can be enjoyed and an aesthetic that one doesn’t need to feel shame or guilt about enjoying.

Natasha: Do you think there’s a British response to public eroticism?

Eddie: Yeah, absolutely. Living in Rome for a long time, where people are much more relaxed about their bodies; but they are also quite superficial about the display of that relaxedness. Italian people are very uptight really, but they’ll display everything like they’re the opposite of that. British people are the opposite, in that they’re outwardly quite uptight, but are really much more open. What interests me is the discomfort of viewing art which does happen anyway. The experience of walking into a gallery is a quite unnatural, discombobulating and discomfort-inducing experience. It just so happens to be the case that if you put a naked body in the gallery, on top of all of that, it makes that discomfort that much more apparent.

Natasha: There are different modes of spectatorship within your work. You’re being tossed from being a viewer of film, to being a reader of text, to being a voyeur of the body. Your position is constantly shifting throughout. What is your relationship to the body in terms of the kind of bodies you employ in your work?

Eddie: There is no specific ‘kind’ of body that I employ, working with dancers, and quite advanced dancers, and that’s really a necessary requirement because they’re somewhat dancing in the performances. Dancers by and large do have a certain type of body. They’re akin to athletes in that they effectively exercise for a number of hours every single day very rigorously and so it’s often quite difficult for dancers not to have these athletic, toned, and muscular ‘ideal’ bodies. In fact, for the current show at the Barbican we made a point, in the call-out for the auditions, of saying that this is open to all types of body shapes and sizes, backgrounds and genders. I would say that the one biggest disappointment in the process of putting this show together was the lack of diversity in the people who came to the audition – not to say that the performers I am working with aren’t fantastic. However, we can sort of invert our snobbery about body shapes and sizes when it comes to people who possess a body that might be deemed the ‘ideal’ body according to our current idea of what that is.

Natasha: It is also easier to project sexual fantasy onto the ideal body. There’s an interesting feedback loop between digital imagery of figures having sex, and the choreographed performances in The Forever Loop, which is showing at the Barbican. How do you see digital culture as impacting on our perception of the body, or indeed on sexuality?

Eddie: Sex is so available at the moment because of the internet. This brings up interesting questions in that I think it’s much more present, and so much more a part of the conversation.

Natasha: How did these graphically rendered figures come about?

Eddie: I wanted to make a work that possessed the quality of this very pivotal scene in the film Who Framed Roger Rabbit, which is one of my favourite films of all time. That film is interesting to think about in relation to your question, because it was made in a pre-digital era, but it has a lot of elements in it that are akin to the way that we all kind of engage with computer screens now, with the digital as an integral part of our day-to-day existence. I like that the film blends the realities of real people and drawn time and space. That’s something that I’m trying to do in this show with these videos and then with the dancers doing a kind of dance with digital reality. They weave in and out of synchronization with one another. In the film there’s a scene with Judge Doom, who’s the main baddie, and who we’ve been led, up until this pivotal moment, to think is human. In that film there’s a politics and a hierarchy of cartoon characters and humans. He eventually gets killed in a harrowing fashion by being run over by a steamroller. Then, in the very next scene he springs back to life as a flat 2D form, flip-flopping up with a saw sound effect.

For me, the scene is completely stunning. It’s a key moment where you realize that he’s actually a cartoon character and so suddenly this conflation of 2D, 3D, drawn, fictional, and real happens; my characters are very directly based on that.

Natasha: In the show the viewer is led very specifically through the structures of the space; indeed it’s almost as if you are choreographing the viewer’s body itself.

Eddie: Yes, it’s really clear that I’ve taken the space head on. In preparing for this show, whenever I’ve had conversations with people about this show in the Curve Gallery coming up, most of the people see it as a challenging space. As I tend to work with the spaces I’m exhibiting in, it has been the absolute opposite for me.

So it’s exciting if a space is weird and unusual. This space is especially suited to my approach as it has an inherent narrative quality where it’s constantly unfolding. As a visitor of the show you’re constantly experiencing something new.

Natasha: Forever Loop is an installation that is also playing with time; you have looping videos, performances, and texts that loop you through the Curve Gallery space.

Eddie: Yes, there’s a lot of different processes happening there. In my mind the show is an essay with these points coming up and then you think they’ve gone away, but then they recur, and cross-reference each other. In an ideal world visitors would spend a lot of time there as many of the works in the exhibition make some form of reference to looping as a phenomenon or a formal structure. The video and performance works are titled It’s like a revolution, which is one of the things that MC says in the show. Revolution implies a looped format, but also revolution as uprising. In the context of this current government it’s really about asking if we can make a revolution happen, or start something new. The politics of the work isn’t intended as moralizing or finger wagging; the show should rather be enjoyable and fun. The other work that literally loops is the wall painting which I actually think of as a sculpture. The title of that work is Sentence and it is one sentence that starts at the end of the space and ends at the beginning of the space, thereby requiring the viewer to really complete the loop. I’ve spoken in very formal terms about the work so far, but actually there’s a lot of autobiographical and personal content in the show. The sentence itself recounts real events in my life, directly lifted from when I was twenty and was in a psychiatric hospital for two months. To be very clear about it, I’m not attaching any romanticism to that, it just happened. It was probably the lowest ebb of my life, but there’s something quite hopeful and positive about knowing you can’t go any lower.

I think the work is quite fun to be with. It’s loud and really gives itself to the viewer whilst paradoxically being able to communicate with dark subjects.