Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910)

Nº1 •

Key Lime Pie

At the beginning of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, two men go out for oysters. Levin, who is self-critical, and spiritually pure, eats without relish; whereas Prince Stepan Arkadyevitch, who is high-spirited and serially unfaithful, strips each oyster from its pearly shell with the reverence with which you might undress a beautiful woman. While Levin remains detached, the Prince devotes himself entirely to the pursuit of pleasure; he swallows the oysters down with ‘dewy, brilliant eyes’, before proceeding to gobble up many fabulous courses of tarragon chicken, parmesan, fruits, champagne and Chablis.

One of the most scrutinised meals in literature, the scene is not only remarkable for its food descriptions (which are drool-inducing), but for the connection Tolstoy draws between food and lust. The way a man eats an oyster, in Anna Karenina, can tell you something about the state of his soul. It can also tell you something about the way he makes love.

Tolstoy was perhaps particularly sensitive to the eroticism of food (in later life he denied himself both, subsisting on a mainly egg-based diet, and refusing intercourse, even with his wife). But as humans, we all have a tendency to confuse our appetites. In linguistic terms, it is difficult even to write about a mealtime without euphemism; the words we use to describe one kind of desire evoke another (‘hunger’, ‘satisfy’, ‘indulgence’, ‘junk’, ‘eat out’). This is because in life, as in Tolstoy, food is never just food. There is a reason why dining is an ancient courtship ritual: to cook for someone is to anticipate a need – be it physical or emotional – and try to meet it.

Cooking – as that other great food writer, Nora Ephron, has written – is a way of saying I Love You. It can also be a way of saying I Hate You. In Heartburn, Ephron’s novel about a marriage breakup, there is an unforgettable pudding scene. Our heroine, Rachel, finally confronts her philandering husband over dinner. Faced with the realisation that he has been unfaithful, Rachel calmly walks to the kitchen, picks up her home-made Key lime pie and throws it in his face. What makes the pie such an effective weapon is that it has been made with love; the act of cooking, for Rachel as for so many other women, is an expression of devotion. Splattered across her husband’s face, the pie symbolises all that love, gone to waste. Revenge, in this instance, is sweet.

Asparagus is a vegetable rich in vitamin K, which increases the blood flow to the organs that need it when things get serious (the penis and the vagina, in short!)

Nº2 •

Aphrodisiac

Food, like sex, is primarily an imaginative experience. Mealtimes derive more flavour from your memories than your ingredients. Nowhere is this more evident than in the records of last suppers requested by death row inmates. The men request fried chicken and burgers and ice cream and biscuits. Which are all, objectively, delicious. But they are also all foods that have the capacity to transport their eater back in time. Ice cream tastes good, in part, because it tastes of childhood.

This tendency to enjoy food on a psychological, as well as a physical, level has a sexier example: the aphrodisiac. There are, according to scientists, no non-medical sexual stimulants in existence, and yet we continue to ascribe lusty properties to a vast number of animals and vegetables. The earliest example is the lettuce, associated with virility by the ancient Egyptians because it grows in thick, firm shoots that, once broken, ooze a white, viscous liquid. Oysters enjoy an aphrodisiac reputation for similar reasons. As do carrots, turnips, aubergines, molluscs, avocados, walnuts, figs and asparagus. In 18th-century France, it was typical for a lady to check whether her husband was cheating in asparagus season by smelling his chamber pot. If she had not fed him asparagus, then perhaps his mistress had. Throughout history, humans have made a dirty habit of ascribing aphrodisiacal powers to any food that remotely resembles a genital. The problem with this methodology might also explain its irresistible appeal; if you look at any item of food for long enough it starts to resemble a genital.

Perhaps the only reliable aphrodisiac, then, is alcohol. Not because it enhances performance (more than two drinks per day impairs circulation and nerve sensitivity, two factors crucial to sexual arousal), but because it lowers inhibitions. According to the historian Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat, the ancient Romans invented kissing so that a husband could tell whether his wife had been drinking wine. Alcohol was forbidden to women in the Roman empire, because the fairer sex was thought to be particularly susceptible to its corrupting influence. Kissing (or so the story goes) was first devised as a canny sort of marital detective work.

Nº3 •

Emoji

We do not seem likely to evolve past the impulse to associate food items with sex organs. Consider the aubergine: thanks to its emoji, this curvy purple fruit is now so synonymous with arousal. In 2016, an online platform was launched where you could buy aubergines and have them delivered to your lover’s door, for only £6.99 a piece.

The Paris Review print famous poems translated into emojis, and an emoji-only version of Moby-Dick called Emoji Dick was accepted into the Library of Congress in 2014 (‘Call me Ishmael’ is‘☎️ 👨 🐳 ⛵ 👌’). Emojis can also be used to spell out whole sexual fantasies. Significantly, the naughtiest emojis are always culinary: 🍆 + 🍑 = sex; 🌭 + 🍯 + 🍯 = threesome; 🦞 + 🦞 = mate for life.

A 2019 report by the Kinsey Institute found that emoji users had more first dates and more sex than emoji shunners. This could be because those with the guts to send an unsolicited aubergine might already be more sexually experimental, but I would like to give the emojis themselves more credit. Perhaps the option to express yourself using a new visual language is a curious kind of sexual liberation. Sending a picture of a vagina is intimidating but sending a picture of a honeypot is playful and, not incidentally, sweet. Presented with a smorgasbord of tiny treats with which to spell out your desires makes desire itself more palatable. Embarrassment is the enemy of sensuality. Emojis will set you free.

Bethany Gaskin is an American food-lover who started the YouTube channel Bloveslife.

Nº4 •

Mukbang

Texting a tiny lobster to your crush might now constitute a romantic gesture. An even more pleasurable experience could be to watch her physically eat one. Bethany Gaskin, a petite, manicured mother from Cincinnati, has made herself a millionaire by gorging on enormous platters of shellfish. Up to thirteen million viewers tune in per video to watch Gaskin lift huge lobster tails to her lips and then voluptuously lick her bejewelled fingernails.

Gaskin is capitalising on the wildly popular Korean internet trend for mukbang videos (a mashup of the Korean words for let’s eat muk-ja and broadcasting bang-song) in which YouTubers live-stream themselves consuming more food than they can comfortably swallow. In Korea, mukbang stars time their videos to coincide with dinner-time hours, so their viewers eating alone at home feel like they’re sharing a meal with a friend. Part of mukbang’s draw is that it staves off loneliness: eating is a communal experience; sharing food with a loved one can be intimate. But now that more and more people live alone in Korea, the best many can hope for is to put on a video of their favourite star eating, and dine along to it. In the US, where Gaskin is a star, approximately 36.2 million people live alone. During the pandemic, when eating alone became, for many, a legal requirement, her subscriber figures skyrocketed.

There is also a stranger sort of pleasure to be found in these videos. Mukbang can, according to physiologists, trigger an autonomous sensory–motor response (ASMR) in the viewer: a kind of soothing, tingling, tickling sensation in your head and neck brought on by the sounds of another human eating.

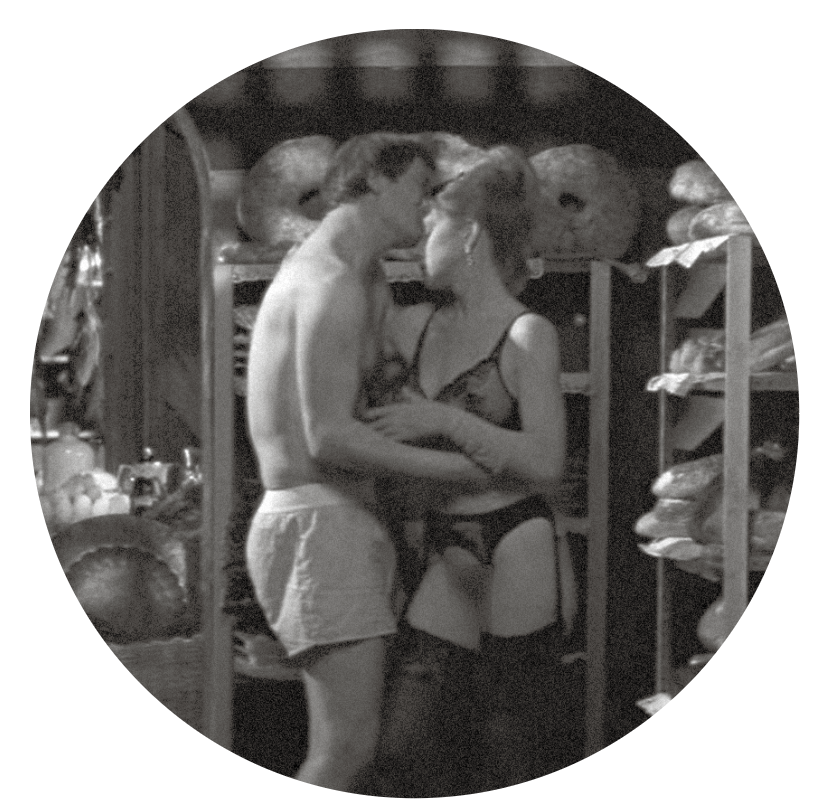

In The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (1989), when Georgina and Michael have sex for the first time in a room filled with vegetables and bread, the camera cuts repeatedly between images of them and images of the chef chopping and dicing food on the counter.

Nº5 •

Meet Me in the Meat Safe

This delightful tickling sensation is presumably intensified if you aren’t listening through a screen, but actually in the same room together. To eat with a lover is not simply to revel in the sounds of their chewing, but to experience a visceral kind of pleasure together. In The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover, director Peter Greenaway turns a tale of a bullying criminal and his unfaithful wife into a profound exploration of the intimacy of sharing food. Across the dining room of a restaurant, the wife (Helen Mirren) exchanges glances with a meek-looking man (Alan Howard). Soon, and without speaking a word to one another, they are making passionate love in a bathroom stall. The spark? When they first locked eyes, they were eating exactly the same dish.

Where the thief eats and belches with his henchman, his wife and her lover are united by a genuine love of food. The chef, who facilitates the affair, recognises their sophisticated palates. He allows them to have sex, night after night, in his bread larder, and a meat safe strewn with the hanging bodies of unplucked pheasants. Food is the secret couple’s connection; the only way they communicate (they don’t utter a syllable to one another until at least 100 minutes in).

The film is surreal. In life, you might not actually want to copulate surrounded by dead pheasants. But Greenaway’s vision of food as a form of foreplay rings true to me. To be in a happy new couple is to eat from the same fork (this is why happy new couples are so nauseating to their fellow diners). Often, the couple will hardly speak; they will simply roll, from bed, to dining table, and back again.

Anthony Bourdain (1956–2018)

Nº6 •

Sexy Chefs

Long before Bethany Gaskin, Nigella Lawson had made a career out of licking her fingers. I do not say this to denigrate Lawson’s cooking; it is fabulous. But her status as a pin-up is worth mentioning because it points to something food and sex have in common. Lots of things can give us pleasure (dogs, friends, long walks on the beach) – but good food is more intense: like good sex, it can excite sensory ecstasy. Watching Nigella eat a spoonful of chocolate ganache is gratifying because that image combines two of our most profound legal thrills. Do you know that chocolate ganache actually contains phenylethylamine? A stimulant related to amphetamine, that is released in the brain when two people fall in love.

Hot chefs are not exclusively women; in fact, the culinary pin-up is more often male than female. Acknowledged sex symbols include, but are not limited to, Anthony Bourdain, Jamie Oliver (aka ‘The Naked Chef’), ‘Salt Bae’ and, lately, Stanley Tucci. In his 2021 culinary travel series for CNN, Tucci wanders around Italy squeezing mozzarella in a way that is borderline obscene. At one point he cradles a great wheel of Parmigiano–Reggiano in his muscled arms and lets out an audible moan as he inhales it.

An interest in cheese is a thing that most pin-up cooks have in common. Also: butter, cream and red meat. Fatty foods have become taboo in Western culture and part of the sexy chef’s appeal is that he or she breaks that taboo by indulging in forbidden pleasures. As Anthony Bourdain himself wrote in A Cook’s Tour: In Search of the Perfect Meal (2001), ‘Food is the new porn … a less dangerous alternative to the anonymous and unprotected shag of decades past.’

Mary Eberstadt explores in Adam and Eve After the Pill: Paradoxes of the Sexual Revolution (2012) the portrayal of the sexual revolution in pop-culture voices.

Nº7 •

Is Food the New Sex?

In an explosive 2009 essay for the Policy Review, the academic Mary Eberstadt took Anthony Bourdain’s point a little further, arguing that ‘food is the new sex’. The 1950s woman applied a strict moral code to sex, while treating food as a matter of personal choice. In Eberstadt’s view, for the contemporary woman, the situation has reversed; food is now freighted with taboos, while sex is much less so. Most provocatively, Eberstadt maintains that our modern-day concern with dietary restriction is a symptom of the fact that we are uncomfortable with sexual freedom: ‘It is hard to avoid the conclusion that the rules being drawn around food receive some force from the fact that people are uncomfortable with how far the sexual revolution has gone – and not knowing what to do about it, they turn for increasing consolation to mining morality out of what they eat.’

Eberstadt’s arguments were widely derided by the left (it is difficult to swallow the idea that a proclivity for almond milk actually signals subconscious aversion to legal abortions). But she does raise some interesting points about food and guilt. It is undoubtedly true that food has become a way of virtue signaling: veganism is couched in the language of cleanliness (it is quite literally ‘clean eating’); whereas fat and meat and alcohol has become a kind of secular sin (the popular British weight-loss company Slimming World allows followers of its regime fifteen ‘Syns’ – treats – per day).

A woman eating without restraint is such an unusual sight that it has become a shorthand, in cinema and TV of the last decade, for deviance – and, on occasion, psychopathy. The protagonist in Killing Eve typically enjoys a snack before she commits a murder, and in David Fincher’s Gone Girl, we are given to understand that the heroine has truly lost her mind by means of a shot of her devouring a burger.

In a way, this view of female appetite is frustrating; as though the most radical thing a woman could possibly do would be to freely eat junk. But it’s tricky, because as with all of life’s most sensual experiences, part of food’s thrill is the fact that it is a kind of forbidden fruit. You cannot just eat and eat and eat, because to do so would be to eventually keel over and die. Guilt, in my experience, certainly sharpens desire.

La Grande Bouffe (1973)

Nº8 •

Sex, Food, Death

In La Grande Bouffe, Marco Ferreri’s infamous movie of 1973, four middle-aged men retreat to a villa in the countryside to do exactly this: dine themselves to death. So divisive when it first came out that fist fights occurred on the Champs-Élysées. This film – depending on which way you look at it – is either a clear-eyed satire of bourgeois excess, or a vehicle for fart jokes. In one unforgettable scene, we see Michel Piccoli, an icon in France at the time, literally die because he farts too violently. Other extraordinary moments include Andréa Ferréol, the film’s unlikely femme fatale, leaving an imprint of her naked bottom on a tart and then eating it, whilst simultaneously making love to the chef. In another sequence, Philippe Noiret chokes to death on two enormous, pink, breast-shaped blancmanges.

At points, this 130-minute masterwork is unbearable – Catherine Deneuve went to one of the first screenings with her lover at the time, Marcello Mastroianni (another of its stars) and was purportedly so horrified she would not speak to him for a week afterward. But I defy any really greedy person not to feel a grudging respect for these gluttons, who not only eat and eat but actually read out recipes for lunch while they are in the process of enjoying breakfast. Squint a bit, and there is heroism to this suicide pact. Not content to wither away in obscurity, the protagonists of La Grande Bouffe have opted for something more romantic. Like Shakespeare’s Othello, they would like to die upon a kiss. To die from pleasure, not from pain. To die stuffed to the gills with titty blancmange. Who, among true food lovers, cannot say the same?