In December 2015, I met Bethan Laura Wood at a serendipitous event, where a joint friend of ours, the curator Sigrid Kirk, hosted a group of female creatives over a Christmas lunch. Sigrid must have foreseen a potential exchange and interest between me and Bethan because she seated us next to one another. I was intrigued by Bethan’s outfit, slightly jealous of her confidence and her bold use of colour throughout her appearance, from layers of her clothing to her curious make-up that included marked dots under her eyes and circles of pink blush on her cheeks, complemented by her extraordinary hat and two-coloured, round glass earrings. The memory of meeting Bethan is still very vivid. ‘Colourful’ is not a satisfactory term to describe her. She carried a mountain of colours, yet her outlook was serene. She grasped everyone’s interest. At the time she was dressing the Hermès shopfront and she told me that she was a designer working across a wide range of mediums. Over the years, she has not only proliferated her areas of production from furniture to carpets, jewellery to lighting appliances, but also expanded on her streams of imagination and scale of outreach. Today, Bethan is one of the most celebrated designers in the UK, working with an international array of clients and pushing her practice further with each commission. I have been lured by every object she has designed, intrigued by her practice that reverberates a unique sense of freedom and elaborate skills that have accumulated through her devoted commitment to invention.

Fruits of Labour, Window display for Hermes, 2014. Courtesy of Bethan Laura Wood Studio. Photo: Angus Mill

Fatos Üstek: Amidst all your innumerable works and commissions, introducing new ideas, new objects into the world, how do you define intimacy?

Bethan Laura Wood: For me, intimacy is about private things.

Fatos: If I was to unpack that question in relation to your work, I’m reminded of the sketches you share that show your thought processes in the making of specific commissions. I personally find that very intimate. It’s as if you’re opening up to strangers.

Bethan: Within my work, I try to have different levels of engagement and showcase intimate sections of the making. The curated images that I publish online are obviously a small percentage of what goes into a piece. But I think it’s important for me to share some of those elements with people who want to be more engaged with the kind of theoretical or more poetic side of a project.

Fatos: In that sense, how is your relationship with social media?

Bethan: I use my Instagram similarly. I enjoy shareing some of my reference points. I use it as a diary, as a tool. But my Instagram presence tends to be more specific to a project that’s live or something that I’m ready to share. And then I may keep certain pictures back because I’m not ready to expose them yet. I’m still kind of digesting them or wanting to keep them for something that I might talk about at a later point. I think it’s lovely to be able to see some elements of making. And because my work is partly about the making or process within it or making conversations about that, then it makes sense to show those elements.

…I’ve long been interested in the idea of how a pattern can function to create engagement between people and objects….

Fatos: Absolutely. I wanted to ask you about the use of layering within your work – a technique that you use to produce additional surfaces. I’m wondering how you personally define the concept of a ‘surface?’ What does the term evoke?

Bethan: I like to engage directly with materials that are technically all surface. Layers of pattern might give an indication of an object being all one thing but it’s actually not a single entity. That’s an illusion I’m fascinated by. For instance, the Super Fake series uses laminates, some of which emulate expensive marbles, but the minute you look at the edge of the piece, the illusion is shattered. There’s something very beautiful about that misinterpretation. Surface detail can also be seen as secondary, or not the main part – just the decoration on top. Personally, I find that contradictory. I often play with and against that notion. A lot of my work starts with details and builds up from there, rather than adding them at the end. There tends to be a notion that pure design can only work one way: when you strip away all the details that are unnecessary, you arrive at the perfect form. I’ve long been interested in the idea of how a pattern can function to create engagement between people and objects. The way that one notation of a particular pattern, or a combination of a pattern and a colour, immediately allows someone to access and understand a piece, connecting it to a certain time or movement.

Moonrock Low–table, Super Fake, 2011. Courtesy of Bethan Laura Wood Studio. Photo: Angus Mills

Fatos: That’s an expansive way of approaching the notion of surface. It seems to be in opposition to the definition of a ‘surface’ as a skin without flesh. It makes me think, for instance, in the arts, there’s a lot of conversation about content versus form. What you’re saying is along the lines of content informs form or at least how the form will manifest. For instance, the tables you designed in the Moon Rock series go beyond the immediate function that necessitates legs and a flat surface that is attached to it on the top. So, would you then say, instead of making a table, you first make the feeling of the table?

Bethan: Specifically considering the Moon Rock series, it only took the shape of tables because laminate is very suited to that type of furniture. It made sense since tables are the most surface-based pieces of furniture – tables are literally flat surfaces and some legs. Later on, I built cabinets, specifically because they are also very surface-focused. The Particle cabinets I created for the Design Museum were inspired by the idea of a container. At the time, the museum was in a former banana warehouse, which gave me the opportunity to readdress how many industrial areas have become high-end luxury spaces. I transformed crates and pallets into posh cabinets – banana boxes became very expensive design items. My process frequently unfolds in this way – I find the archetypal form that best suits the concept.

…the way that we collect sentimental commodities that can be simultaneously understood as worthless and incredibly meaningful…

Fatos: I think it is interesting that the history of a location informs your production. I imagine this is one of the reasons that you take a lot of residences, or travel for commissions – an emotional, social, functional archaeology of the space informs your thinking. The outer form and outer skin of something becomes even thicker, in this approach. In the Super Fake series, it’s almost like you introduce a U-turn, a twist into this whole phase of production. And I’m so inspired by the way you take up derivatives of concepts such as ‘fake.’

Bethan: The tension between depth and surface in my work seems allegorical to the kind of contradiction produced by the difference between ‘real’ and ‘fake.’ Often things are not what they seem, and there is a negative side to only understanding things at face value. And then, of course, there’s another side, where you can discover a lot of depth at surface level. Often, I like to be quite tongue-in-cheek or play around with big ideas of hyperreality. That approach is very present in the Super Fake pieces that I’ve done more recently. For example, the carpets that I designed for cc-tapis capture this experience of the virtual becoming the new reality.

I think in life, there are different ways of reading and seeing. That’s the beauty and the dilemma of being human. For instance, I often think of our magpie-like tendency to covet objects; the way that we collect sentimental commodities that can be simultaneously understood as worthless and incredibly meaningful.

In times of crisis, the arts are regarded as inessential. During the pandemic, the UK government has really failed to support the creative sector. There was even a controversial poster depicting a ballerina who was encouraged to retrain as something more ‘useful.’ Yet it’s also been a time of creative outpouring. People needed the arts to deal with how emotionally draining this period has been. The commission I did for the Wellcome Collection just before Covid-19 touched on this idea. Little did I know how relevant it would be in the following year. The piece, which was made for the sculptural centre, is a jukebox that plays different musical compositions from epidemics throughout history, from AIDS to Ebola. It explores how we use music to console, educate or process our reactions.

Fatos: I suppose it’s the nature of value – the attributions of value to objects and experiences.

Bethan: The way that values can shift exponentiality in a relatively short amount of time is quite incredible. Like in the case of pineapples. In the 17th century, pineapples were the most expensive party favours, but now they are abandoned on supermarket shelves for less than a pound. I’m drawn to the journeys that materials or objects have within our collective consciousness: the highs and lows of mass consumption and insignificance. It’s fascinating that democratising things and making them more accessible can also lead to devaluation. I find it all very interesting, although I don’t necessarily claim that I have the answer to these contradictions. I’ve always been curious about these kinds of complications that we can never fully explain. What produces consumer obsessions or passion or intense emotional attachments towards certain items?

HyperNature. Courtesy of Artflyer. Photo: Alexia Antsakli Vardinoyanni (top) Courtesy of Architectural Digest. Photo: Jooney Woodward (bottom)

Fatos: What resonates with you while you are filtering layers of information, history, methods, surfaces, textures? How do you initiate your relationship to these objects of desire?

Bethan: During my studies, I began looking at materials that can only exist because of industrialisation. Like Pyrex, for example. Usually, industrially produced glass is sold commercially in extruded tubes. I’m attracted to materials that carry signifiers that they are part of larger production systems. There are all these layers of production – we don’t always see them. Nearly all raw materials must be processed in some way, unless you’re going into your backyard and digging out your own clay, which is also a really nice way to work. Pyrex offered me a lot of dexterity when I was designing the chandeliers. I used the extruded tube form, the high strength and thickness of Pyrex to allow me to reduce the amount of metal armature needed so the piece could be made almost completely from glass.

Fatos: Do you have any partners in crime?

Bethan: I love making work about people with people, and experimenting, editing with somebody. My work can also be strongly affected by meeting people or getting the opportunity to work with a particular individual who is a specialist in the material. It’s wonderful to develop specifically around that connection, in relation to their abilities and strengths.

Fatos: When you’re making new work, do you produce for yourself? Or do you imagine its future users, and how they will engage with the works visually, emotionally and sensually? Do you follow threads of pure imagination or a blend of imagination with pragmatics? In short, how would you define your relationship to your production?

Bethan: If I make a piece of work that I wouldn’t want even in my own home, then I begin to question myself. However, I’m also aware that I have a home that’s in a particular taste and size, so not everything fits or is quite suitable. I tend to lean towards very small proportions. A lot of my work is built from small elements and then scales up. Frequently when I’m working forms and bodies for furniture, I need to check that I’m not making something too small because that’s my default size. I live in London, in a flat without a huge amount of space. I need to remind myself that other people might have more room for bigger furniture. And the practicalities of a piece also come into play. Say, I decide to make cabinets, then I must spend time understanding the proportions, and the situations that would most likely be used in. It’s good to know the size of a standard magazine, bottle or drinking glasses, because there’s nothing worse than making a cabinet that can’t contain the ordinary things that most people would put inside it.

Fatos: Do you have a specific technique or a method?

Bethan: To ensure I’m working in scale, I will often also make a guide that’s in proportion to my height, against the piece I am modelling in, for example Rhino (a 3D computer programme), because I can understand things best in relation to my own body. From a purely practical approach, if I’m making a piece of furniture such as a chair, then I want it to be comfortable. And I also want to be analytical. In the overall aesthetic, I try to include a nod to the things that drew me to make that project in the first place.

Fatos: Do you enjoy making references that are accessible? And how intrinsic are such references to your work?

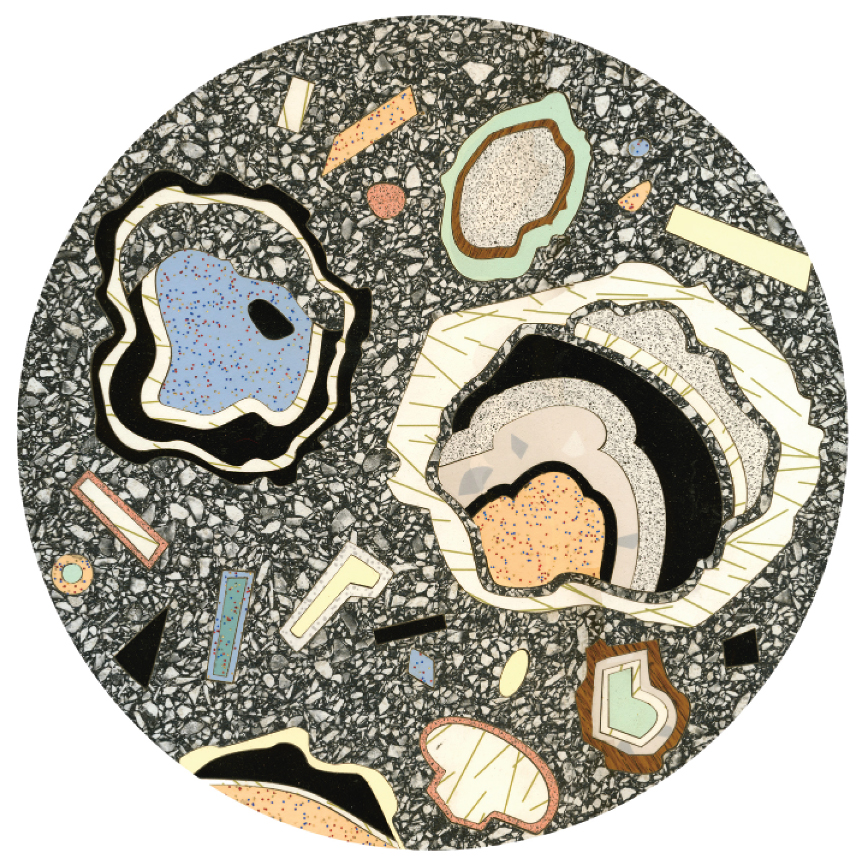

Bethan: With the Moon Rock pieces, some people see straight away bacteria more than rocks, others see fried eggs; some people see shells and oysters or ice cream. It’s incredible that the interpretations can shift so much. In my house, I have a couple of lamps, one from the Totem collection and one from the Sputnik collection, which is made in Pyrex and contains quite a few specific references. The other day, my neighbour dropped by, and he picked up on the Metropolis (1929) robot depicted on the Totem lamp. I reckon it is because he’s into film, actually he’s a director. He understood the nuanced difference between the kind of science fiction that I utilised for Totem is an earlier period of the genre from the 1920s, rather than say, from the 1960s, evoking Barbarella’s gun. I was happy that someone else could read these nods in the foam. Other people don’t make these connections, they see shapes that resemble a jellyfish or a clown. I enjoy keeping the aesthetic references open so that people can find their own engagement.

The million-dollar question is: how do you make something that everyone wants to keep? For me, that’s part of my way of making those emotional connections between inanimate objects and someone’s imagination or their reading of the world, because they start to build the story of the piece themselves, through the cultural codes that they can connect with things that they’re interested in.

Fatos: How would you describe yourself as a designer?

Bethan: I’m a very visual and tactile person. I like to work on projects where I can be very involved – I enjoy the meditative, immediate process of weaving or colouring by hand. Sometimes it is very nice to get to do a project where I can work with the most basic of tools like drawing by hand. Right now, I’m working on some projects with cc-tapis, based on my drawings.

Fatos: Do you feel you loosen control when you work with machinery or other means of production than the immediacy of your hands?

Bethan: Well, to me, that’s a bit of a false dichotomy. Just because industrial weaving machines are more industrial doesn’t mean there’s less of a process involved. When I worked on the Guadalupe repeat for the Moroso Showroom, I became really fascinated by these machines; the rules that govern their systems, versus the way that human hands work. It was amazing to see how the technicians re-interrupt the colourways based on the rules of the machine and what makes a structural weave. I learnt that a minimum of around one hundred metres of yarn is required for setting up a loom. It’s quite wasteful and not very cost-effective. For every colourway, you need a whole reel of yarn to be set up every time. So I wanted to figure out how to create different colourways where the master yarns (five of them) stayed fixed and then by selecting the right different warps I could produce a set of colourways that looked completely different from each other.

Fatos: I feel like you love dancing with colours.

Bethan: I regard colour as a dominant partner from the beginning, rather than an element that’s added in at the end. For each project, I create a palette that becomes like another language. Colour is subjective too. When blue is placed next to yellow, for instance, the yellow will pull out a different variety of depth from the blue than when it’s placed next to another colour. That’s why, when I did the repeating fabric with the weave machines, changing the colours that were in conversation, it was like swapping dance partners. I was able to completely change the overall colourway of the final piece, and that was an entirely new way of working for me.

Fatos: What do you think about colour theory?

Bethan: What I’ve learnt about colour has mainly been from first-hand experience. For example, particle marquetry, working only with wood patterns, taught me a lot about the secondary colours in brown. It was via browns with a red base, contrasted by ones with a yellow base, that I discovered combinations that worked together, rather than relying on the overall light to dark. I had an intern from Eindhoven who was trained in Kandinsky style colour theory, which I was very envious of. I’d love to do a course and see if what I’ve understood aligns with traditional colour theory.

Fatos: Do you get frustrated by obstructions or challenges?

Bethan: Even though it’s frustrating and complicated sometimes, that experience of wanting to make a certain object is like fantasy meeting reality. I suppose I’m speaking about the kind of experiences that provide a deeper understanding into a process; that grants you even greater respect for all the people that nobody really sees behind the curtain of production, like technicians. Without them and their abilities, you wouldn’t be able to translate your precise desire to have three pink or blue squares next to each other into the rules of their specialty. I think that kind of translation or compromise between the different worlds and languages is super exciting. I like the challenge, or the disruption of having another partner come into play because having a conversation with yourself can be lonely. There’s always an element of it that you can’t control but it produces something that couldn’t exist without the other person. I like the addition of an element or thing that I don’t get to necessarily choose all the rules about, because the results couldn’t exist without that conversation. Sometimes when you aren’t given rules – if you can use any material you want no matter the price, when the opportunities are so vast – it becomes almost pointless or very difficult to tangibly get what you’re doing. There is no ground to go back to – it’s all floaty – whereas if there’s points that you must attend to, it gives you building blocks.

Commissioned by Perrier-Jouët in 2018, HyperNature blurs the boundaries between art and design, creating a piece that stimulates dialogue. To inform her aesthetic, Bethan took inspiration from Maison Perrier-Jouët’s connection to Art Nouveau, referencing both the stained glass windows of the house, and the exquisite colour, ombré, in the work of Émile Gallé, who also designed the iconic logo on the Perrier-Jouët bottle. Courtesy: bethanlaurawood.com. Photo: Global Studio

Fatos: What is your secret guilty pleasure?

Bethan: Giving myself the excuse to go to a flea market is my guilty pleasure, but I tell you it’s work! I just love the energy of seeing and meeting people; observing what they pick up and the way the objects are displayed. It’s a very particular experience compared to what you get from shopping malls or shops. Otherwise, I stream movies and series and TV while I work. That’s something I can’t do when I’m writing – I find it too distracting. But when I’m trying to zone into drawing, like a technical drawing, or sketching for three days, then often my guilty pleasure is to put on certain types of movies that might get me in the mood. I remember when I was staying late, quite often I was staying at the studio until after dark, I got into putting on dodgy horror movies.Other times, I enjoy watching creative-type movies that put me in the right headspace. I don’t know if that’s guilty enough for you!

Fatos: Your practice is so very playful and inspiring.

Bethan: I definitely am all about having fun. I like my work to be playful. To me, play is an important thing to do. The freedom that you derive from play that’s not fixed allows you to learn and create. Whereas if you remove play, or the concept of playing, it’s like removing that whole experimental area.

Fatos: What do you dream of making?

Bethan: I was a huge fan of the Tottenham Court Road before it was redeveloped. Eduardo Paolozzi’s murals make transitional spaces interesting. I have always been drawn to being physically involved in artwork – I’d love to do something in a public space like a subway or train station. Places that are a mash-up of functionality and pleasure are so intriguing.