Contrary to stereotypes, Tshegue practices the fusion between afros rhythms, garage rock and electro trance and club-culture production. At high temperature! Tshegue is the name given to the little street boys in Kinshasa, where Faty Sy Savanet was born, the singer of this hot new Parisian band that ignited the European stages. A hoarse and souly voice, with dense and intense phrasing, boosted by epileptic rhythm, tribal trance, concocted by the alter ego in the project, Nicolas Dacunha (a.k.a. Dakou), a native of the Parisian suburbs. The nuclear formula of these free electrons has something to shake you from the head to the feet…

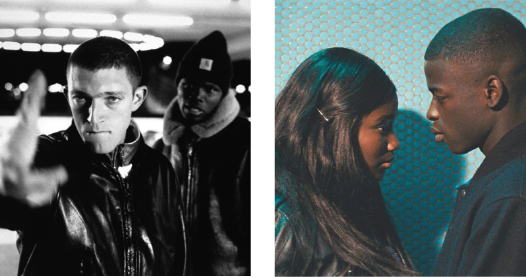

Dakou’s influences from Cuba, Faty remembering Kinshasa, Dakou with the drums, Faty with the voice, the elements were assembled in Paris to create the project which brings a powerful, refreshing energy to the band’s music. As much as Faty might have wanted to keep a low profile before it is time to actually go on stage, it is hard to ignore her entrance through the main door of the venue. The atmosphere becomes mesmerizing when we all see her perform in the club. Faty’s long braided hair toss contains a magnetic power. As the playful adjustment of the oversized white jacket she elegantly wears, sliding up and down on her shoulders, the performance carries a feminine Moses effect reminiscent to godfather of soul James Brown’s ‘Please Please Please’ ‘cape act’. Savanet has become a master at turning attention into a mirror. As the lead singer of Tshegue, a duo born out of the pulsating cultural mélange of the Paris banlieues, she has experienced first-hand the power of remaining unclassifiable. Savouring the dancing qualities of ndule, the Lingala-language music she heard everywhere before moving to the French capital aged nine, as much as she reveled in the riffs and tilts of Black Sabbath. Faty Sy Savanet is accompanied by her musical partner who has the African-sounding moniker Dakou. The French-Cuban producer Nicolas Dacunha, who adds another hemisphere of inspiration as the percussionist of the band driven to the drums and the beats by his Venezuelan heritage.

Tshegue at Motel Mozaïque. Photo: Juri Hiensch

The two of them are, basically, a walking Rorschach test for those with the need to squarely identify the artist within the art. What kind of audio output are we to expect from a duo with those urban backgrounds? That’s where Tshegue does the talking: the band’s first EP, Survivor, is an enthralling exquisite corpse that owes as much to punk as it does to Congotronics. The lyrics, in French, English and Lingala, examine the bonds of the diaspora and the liberating realization of not having to explain oneself in matters of origin or gender.

The band’s promo materials focus mainly on the lead singer Faty, which would appear to give Tshegue a mostly powerful feminine energy. Their current Facebook cover, for example, is a video by filmmaker Melanie Brun that takes its sweet time focusing on her hips, her smile, the way she shies away under her long mane of braids, the gesture of a protective embrace from – a rare glimpse of – Nicolas. There’s no way around it: she’s an objectively attractive woman, and the camera knows it. But then, without warning, she looks back at the lens and faces down the gaze, subtlety defying the object–objectifier dynamic. Later, the mishmash of clips reveals that her dancing is as much a display of athletic strength as it is an evocation of sensuality, with pronounced biceps and nipples given equal camera time. Faty is, on her own terms, as willing to provoke observation as she is willing to question the observer on their fixations. ‘What exactly is it that you expect to hear from a woman who looks like me?’ she seems to ask.

As a multilingual, multicultural, dual-gender band, Tshegue is almost an inside joke, with a wink for a punchline: whatever it is one might expect from either one of its core members – sartorial choices, musical influences, power dynamics – it is bound to be turned on its head.

Minas Baers: There’s a recent photo-shoot that caught my attention. Usually, it’s just you, Faty, as the face of the band, but this new one features the two of you, wearing contrasting versions of a very loaded piece of attire: a trouser suit with a strong jacket, which is something traditionally associated with masculinity. What’s the message behind that choice?

Faty Sy Savanet: When I wear clothes, I don’t ask myself any questions about sexuality. For me, it’s all about the fabric itself and whether or not I like the garment. But indeed, I’ve got no issues with mixing the masculine side and the feminine side. I think they go well together.

Minas: Is there an intentionality behind the fact that you’re the face of the group?

Faty: When we started the project, Dakou didn’t want to be on camera! [Laughs]

Nicolas Dacunha: That was my choice, from the beginning. There are some amazing photos of Faty that I found quite beautiful; she does that more naturally. But then, Faty quickly told me that I needed to start showing up in photos.

Faty: We needed to start projecting our view on equality, the dynamics of a duo. We make music together. It’s not a matter of gender: we complement each other. It is true that I said he should be showing his face a bit more [laughs], because if you wait too long, it’s going to get weird.

Nicolas: She told me that, and that’s where the photos you saw came from.

Minas: And it came with an egalitarian outfit, then, even with the complementary colours of red and green.

Faty: Very much! The look is even a bit sixties, which we love. We each have our own style, but we also love the same fashion references. You see, I liked the colours because they were beautiful. We just wanted to celebrate the fact that we were taking our first [Tshegue] photo together, in full colour. But what you got from that was that the trouser suits promoted equality?

Minas: Indeed, it’s a strong symbol.

Faty: Cool! That’s great!

Minas: On this side of the world, there’s a fetishization of the brown and the black woman that still exists to this day.

Faty: Like many women of colour, I’ve had experiences like that, but I wanted to break away from it, leave it behind. You go through that in the beginning, running through a wide range of emotions – from anger to rebellion. I saw myself as a woman first, instead of a black woman. I was raised as a mix of many countries. So if you see any sort of fight today, that’s unconscious. I have no desire to be rebellious. I’m not angry. If you’re angry, it’s difficult to be creative, and then the message doesn’t reach people. There are many people who get mad at that situation, but I’m done with it.

Nicolas: I am not a black woman, but I do try to understand where she comes from. Her image is associated with the group, and it’s not some sort of vindication: she lives with that, but not everything revolves around it. In our music, she’s the same woman she is in her daily life.

Faty: A free woman! We’re in 2018, and people in our grandparents’ era died in the name of incredible things. They left us a great heritage, and now it’s like a relay race. We are in a continuity, and in order to move forward we can’t be thinking of bringing back the dead. I can’t keep on crying.

Shot in Abidjan, capital city of the Ivory Coast, the striking new video harnesses the primal energy of ‘Muanapoto’s kinetic drumming loops, beneath the no-f*cks-given attitude of frontwoman Faty Sy Savanet’s rhymes, to articulate a story which is actually about silence and isolation. Speaking about the film, which tracks a profoundly deaf and mute young girl negotiating her way out of a world devoid of sound, Argentinian directors Pantera say; ‘From the moment we first heard “Muanapoto” we knew we wanted to make something that did justice to its insane rhythm and trance feeling. “Muanapoto” speaks for African immigrants in Europe who upon arrival are forced to deal with the unknown, surrounded by new customs, foreign languages, different food and climate, all of which can lead to feelings of alienation. “Muanapoto” also feels like a release, a letting go, and that translates to the girl in our video, who feels the need to express something and is able to do so through dance and her body.’ PANTERA is a group of filmmakers from Buenos Aires, composed by Pato Martinez, Francisco Canton and Brian Kazez.

Minas: We’ve only recently seen films that give voice to the narrative of the young women of African origins living in the Paris suburbs, where you both come from. Why do you think it took so long to hear the female point of view in that story?

Faty: It’s true! Thanks to matters like working rights, today, we as women can express ourselves a lot more. However I’m not insulted because I’m a girl and I sing rock. There, personally right now, I’m fine in fact! [Laughs] I do not think there’s any problem – that’s why you make art, it’s to break all those codes.

I am engaged by my story, actually. I will not pretend to speak in the place of others, I am talking about where my place is. If you are not good with your person, it is normal that the image you diffuse is a little distorted; but if you know where you are, by your origins, your sex, your desires, your impulses and your emotions… Do you see what I mean? That’s why it’s difficult for me, these stories of feminism: these questions refer to codes that I wanted to break hyper-young, teen, because there are other fights. I’m a woman, I’m engaged – you’re engaged from the moment you’re alive and trying to hang on to life. So yes, I’m committed, but afterwards, I will engage on things that affect me; I will not commit myself to things I did not experience. That’s why the fight of feminists, it’s complicated for me – because today, there is something that is ultra-venerated with that. It’s certainly a question of positioning, but I do not ask myself that question in fact; I do not want to go into these stories of feminists. Yeah, because I’m a woman already, so obviously I’ll defend the cause from the moment when…

Nicolas: There are so many mothers and grandmothers who have done so much for this generation. Once again, I am not an African woman, but I know that, in the neighbourhoods we grew up in, mothers have had an extremely important role. Thanks to those mothers, women today can express themselves. You’d think otherwise, but the situation in the suburbs is a very matriarchal one. Kids are raised by their mothers.

With 12 million inhabitants, Paris’ metropolitan zone is the most populous area in the European Union. Forty per cent of young adults have at least one parent of foreign origin – mostly Maghrebi or from sub-Saharan Africa. And yet the representation of the city in mass media sticks mostly to the boundaries of the twenty-district snail, which houses a population of slightly more than two million. Foreigners who consume cultural exports are faced with the Mathieu Kassovitz paradox: to many of them, just by sheer way of indirect exposure, contemporary Paris resembles something closer to Amélie than to La Haïne. Some twenty years ago, actor and director Kassovitz was one of the first to showcase the capital’s housing projects as liminal spaces, as well as the microaggressions that many first-generation French African young men face when they attempt to leave them. La Haïne was hailed as the 400 Blows of the nineties suburbs. And yet, despite the critical acclaim, no female version of the movie emerged afterwards.

That finally changed some five years ago, as the female perspective of the banlieue has come alive on screen with two celebrated films released in quick succession: 2014’s Girlhood and 2016’s Divines. Both movies highlighted the importance of female friendship and togetherness in an environment that insists on dividing people, but while the former focused on the binding effects of class and race, the latter added a layer of sexual self-discovery. There are golden scenes where the lead character, a Muslim girl who only wears a burqa for shoplifting purposes, realizes the effect her body has on the opposite sex. As much as she previously tried to run things by talking and looking tough, she finds more power in upending fetishization, baiting-and-switching the expectations of the men around her who try to mould her into a passive recipient of their agenda. The most telling part, though? The character’s weapons of choice to exert power upon these men, no matter their race, are nearly always music and dance. That, if anything, is right up Tshegue’s alley. – Minas Baers

Minas: As a matter of fact, in your song ‘Survivor’, throughout the lyrics you can hear a mother speaking to her daughter about having the resolve to overcome challenges. It’s not a man speaking to his child.

Faty: It tells the story of a woman speaking to her daughter, and they’ve arrived in another environment. They have to deal with a change in things like temperature and they’re trying to understand everything. She reassures her daughter, but she does so harshly: there’s a severity to her, because she wants to raise a survivor.

Minas: There’s a certain resistance to accept the stories of Africans or Latin Americans who are into music considered solely for other audiences. Faty, you were into Ozzy Osbourne; Nicolas, your heritage is filled with Caribbean percussion. It takes a lot for some to understand that people who look like you can be many things.

Faty: Story of my life! [Laughs] It becomes funny, even, because we tend to stop at some sort of physical judgement. But it’s also funny because it has allowed me to quickly ascertain what it is people think of me. I mix a lot of languages French, Lingala and a language that even doesn’t even exist, I want to unite my Congolese origin with my taste for rock, soul and hip hop. I’m rich in mixes, but I’ve seen people who stop merely at the image they can see. Being this way works as some sort of protection. There are moments that I feel a responsibility to explain these things… but I don’t like to feed that any more. Feeding it means explaining myself as a person.

Nicolas: Even justifying yourself.

Faty: But if it seems normal to me, why should I explain it? My friends, family, those close to me… We know we don’t come from a single place.

Kinshasa is the second-largest city in sub-Saharan Africa, with a current population of nearly ten million people. The best way to describe the bustling metropolis would be voluptuous loudness: loud talking, loud traffic, loud living. The Lingala language sounds like a song in itself. On top of that, music crops up in the streets with fast ndombolo here and rumba there, some hints of likembe constantly spilling out from bars, shops and markets. Faty lived in the city, right next to a bar, during the reign of kwassa kwassa. And yet, from the noise and everyday musical porosity emerged a fan of garage rock and Black Sabbath – something quite evident in the desperate drum speed, the defiant guitar riffs and the Ozzy-like screams of ‘When You Walk’, one of the songs on their EP. A few months ago, before a show at La Ferme du Bonheur in Nanterre, the duo was asked to pick their musical influences from a briefcase full of vinyl. Faty went straight for Speak of the Devil, Ozzy Osbourne’s 1982 live album. ‘This speaks of freedom on stage,’ she explained. The loudness of freedom.

The world seems to agree with Tshegue. Judging by the first months of this year, multicultural blackness has indeed stopped explaining itself, opting instead to celebrate the layered richness of its own universe without having to dissect its choices in order to provide others with a sense of normalcy. First there was the global box-office phenomenon of Black Panther: Ryan Coogler’s Pan-African film quietly took inspiration from the Maghreb to the Cape to present its own vision of beauty and cool.

Beyoncé unapologetically turned her first headlining performance at Coachella, long the domain of the white hipster, into a celebration of the step-dancing and marching-band culture of historically black colleges and universities. To many people in the audience that night, the opening song in her set was new… however, it was actually ‘Lift Every Voice and Sing’, a song crafted in 1905 by J. Rosamond Johnson using a poem written by his brother, James Weldon Johnson. Dubbed America’s ‘Black national anthem’, ‘Lift Every Voice and Sing’ was embraced by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1921 as its official song and continues to be a hopeful reminder of how far African Americans have come. Childish Gambino racked up more than 100 million YouTube views in a few days from people trying to decipher the obscure references in ‘This Is America’. And as Meghan Markle as a half-black woman walked, gospel choir and all, into the British monarchy, #BlackExcellence trended globally on Twitter. Judging by these pop culture moments, the roles of the outsider-looking-in are becoming racially blurred – and in some cases, even reversed.

Minas: Likewise, the first time I heard ‘Muanapoto’ on Spotify’s Release Radar, I liked it, but I had no idea what it was in terms of genre. I could not define what it was, and I loved that.

Nicolas: With our music, beyond who we are as individuals, there are no limits. Music allows you to do that in today’s society. As Faty says, if the world worked the way music does, we’d all be better off. We don’t tell ourselves: ‘We have to make African music’ or ‘we must play rock’. We don’t even ask ourselves that question. It’s just the way we are.

Minas: 2018 is an interesting year to be black.

Faty: It’s in fashion! [Laughs] People are starting to understand that there are things happening elsewhere.

Tshegue at Motel Mozaïque Photo: Juri Hiensch

Minas: Where is that elsewhere on the EP?

Faty: You can hear the legacy of the Bantu music that travelled to Cuba. When you play, I can even hear Congolese rhythms.

Nicolas: You can’t hear Cuba on its own or Venezuela on its own, it all comes together. African music travelled so much that you can find these similarities in a plethora of countries. When I was walking through a night market in Thailand, I heard the tac-tac-tac tac-tac… that’s the Cuban clave. But it was traditional Thai music with the same rhythm! This is why Tshegue does not embrace one but many rhythms.

Faty: We’re like a pondu, a Congolese dish I love. It’s made from mandioca and aubergines and you have to work at it for hours. But I don’t make it the same way my mother does: because I grew up in France, I tend to add some spices I find here. It’s the same thing with Tshegue: we’re not attempting to make photocopies of Africa. We are who we are.