Lupanare Grande

fig 1:

City of Sin

For many people, the term ‘City of Sin’ is associated with Amsterdam’s red-light district. Las Vegas might also come to mind. Earlier examples include the biblical Sodom and Gomorrah, but also Pompeii. Legend has it that the sexual behaviour in Pompeii got so out of hand that it riled the wrath of the gods, leading to the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. Among the remains archaeologists discovered loaves of bread still in the oven, human bodies and pets with facial expressions frozen in a state of agony. One could imagine couples being frozen in the act of orgasm as a little death. To their surprise – and for some, awe – archaeologists discovered many erotic artefacts like statues, votive objects and household items adorned with sexual elements, illustrating an attitude towards sexuality that was more easy-going than in their own time of the 16th century. According to some researchers, the city might have numbered more than forty brothels. The prices were much cheaper than elsewhere, making it a bit like the Amsterdam or Pattaya of the Roman Empire if you like. One of the most famous brothels whose remnants can still be visited, is the two-storey Lupanare Grande or ‘big brothel’ – though it only had ten rooms, which must have been a lot in those days. If you don’t mind a little crash course in Latin, lupanare means ‘wolf den’; lupa alludes to both the noun prostitute and ‘she wolf.’ The ten cramped, windowless rooms were only separated from the ante-room by curtains. Inside, there was a stone bed with a mattress on top – not so inviting if you’d ask me. The place was known for its erotic paintings of which it is not clear whether the images were advertisements for the services offered or a means to arouse the clients’ desires. Inscriptions indicated the price of the services: ‘The house slave Logas, 8 As’ and ‘Maritimus licks your vulva for 4 As. He is ready to serve virgins as well.’ More than 100 inscriptions were left behind by customers, a bit like TripAdvisor avant la lettre carved in stone. My personal favourite is ‘Hic ego puellas multas futui’ (‘Here I fucked many girls’). ‘Hermeros screwed here with Phileterus and Caphisus’ is also not bad. Besides brothels, there were public bathhouses where sexual services were provided, as illustrated by the many, often explicit, frescoes of various positions involving two or more people.

Domus Aurea, Rome

fig 2:

Nero’s Golden Palace

This was all peanuts to Emperor Nero, though, a sadistic and cruel psychopath, known for his decadent orgies that would go on for days. At his bacchanals, guests would eat exquisite meals until they vomited into bowls especially for that purpose, while engaging in orgies between or after courses. If he needed light, he would hang Christians from

torches and burn them alive. After the Great Fire of Rome, while the city despaired in need of food and housing, Nero built his ‘Domus Aurea’ or ‘Golden House’ with 300 rooms in polished white marble. Within the palace grounds there was an amphitheatre and a complex of bathhouses. It was known as Nero’s sex palace where the bisexual emperor would throw his legendary orgies. The complex was a massive building overlaid with gold, ivory, and mother-of-pearl. It was

guarded by a 37-metre-high statue of himself called the Colossus. The dining rooms had ceilings of ivory, with panels that could slide back to let a rain of flowers or perfume fall down on his guests from hidden sprinklers. A revolving circular dining room rotated day and night, another sign of his extravagance and apparently a masterstroke of antique engineering. In short, based on its floor plan, Nero’s palace was a decadent labyrinth.

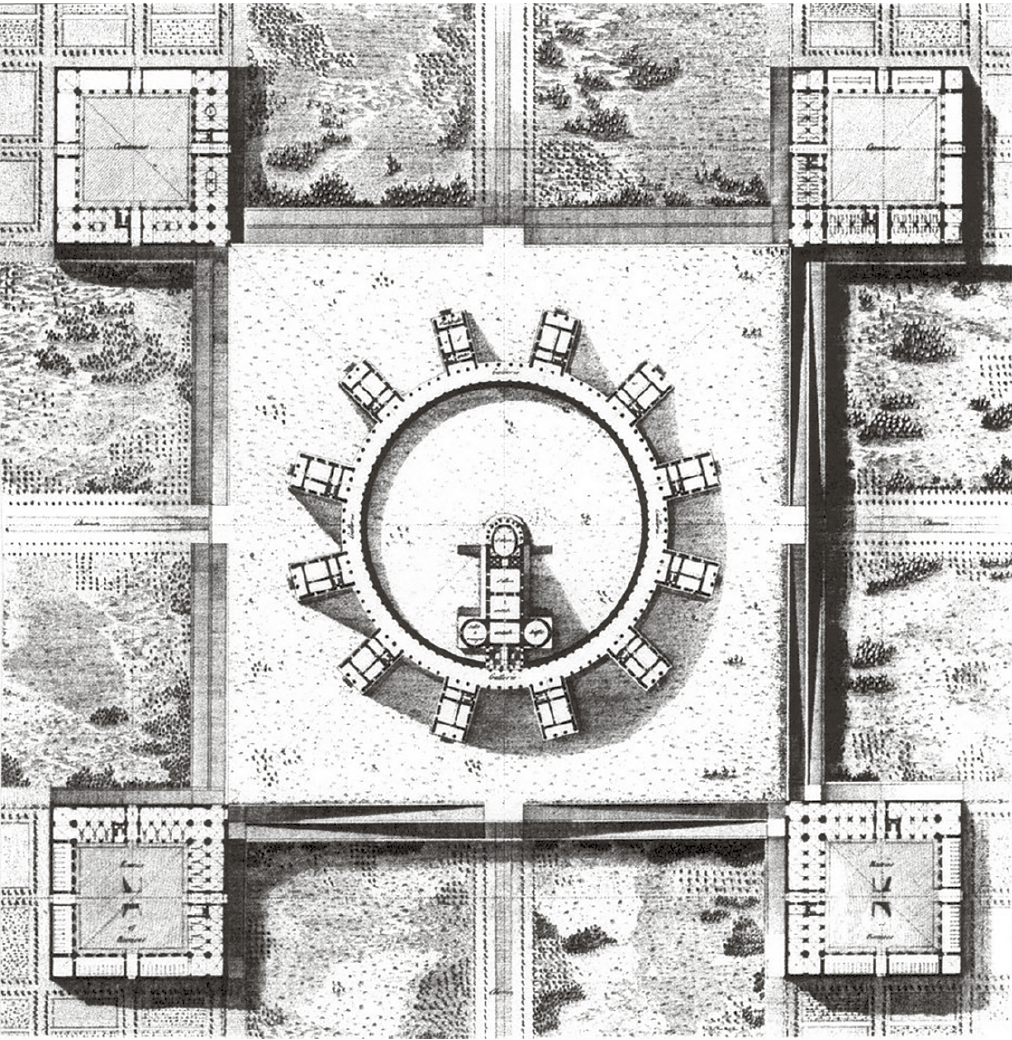

Ledoux’s design for a house of pleasure in Montmartre, Paris.

Pretty self-explanatory.

fig 3:

Claude-Nicolas Ledoux

As one might remember from high school, churches are often built according to the shape of a cross, especially when Roman or Gothic in style. But some architects have been more creative. Take Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, the 19th century utopian architect. He made a visionary plan for the Ideal City of Chaux, better known as the Salines de Chaux. Though only partially constructed, the UNESCO-protected site is impressive and rightfully considered his masterpiece. Built between 1775 and 1778, the building functions as an entrance opening on to a semi-circular space surrounded by ten buildings. Full of symbolism, it was mainly a practical solution for the various functions to be combined harmoniously, such as, for instance, a pavilion for a washhouse, positioned over a bakery. The disposition of the various buildings is also due to safety and hygiene. The semi-circular form allowed surveillance, with the director’s pavilion, the house of the bourgeois master, serving as a symbolic giant eye to prevent salt smuggling. The design recalls Jeremy Bentham’s prison architecture of the panopticon, wherein inmates always have the feeling of being watched without actually knowing if that is indeed the case.

The site was initially supposed to include other buildings. The most striking was Oikéma, built according to the shape of a phallus. Symbolism is also clear in the Teatro Regio Torino built two centuries later by Carlo Mollino, shaped like a womb to express a feeling of shelter. The phallic form was instrumental in conveying Oikéma’s programme as a brothel, comparable to Ledoux’s 1779 design for the House of Pleasure in Paris. His practical solution sought to rationalise prostitution, from the perspective of safety and hygiene. This resonates with the mega-brothels created more than 200 years later in Antwerp’s red-light district or the Pascha in Cologne, a twelve storey high rise that boasts being the largest brothel in Europe with around 120 prostitutes and 1000 customers a day – something the two-storey Lupanare Grande could only dream of.

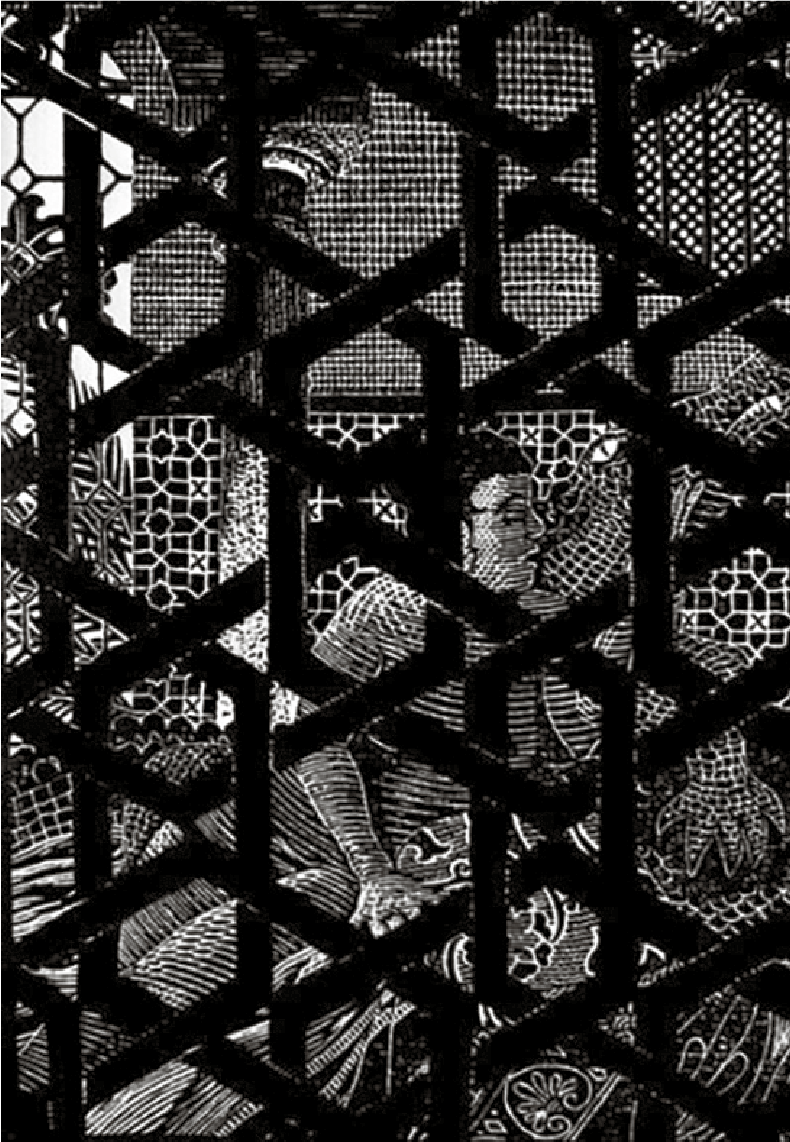

Don’t look too closely between the gaps, it will sap your strength.

fig 4:

Latticework

If Bentham’s panopticon was an institutional way to exercise surveillance and control, with probably the occasional perverted guard enjoying what he saw a bit too much, latticework moves closer to voyeurism. The criss-crossed pattern of strips of building material – most often wood or metal – forms a network. It can be ornamental and functional, filtering light and offering some privacy, used often in hot countries like Spain, which borrowed it from their Arab-Berber occupiers in the eighth century. In Spain, it is called celosías and the latticework is often built around patios and gardens. In India, it is featured in houses of the rich or nobility, around a baramdah or veranda, surrounding each level of the house and leading into living areas, or around balconies on the upper floors that overlook the street. The device was often used by peeping Toms.

In 1931, the Home Insurance Building, designed by William Le Barron Jenney and constructed in 1884 at the northwest corner of Adams

and Clark Streets, was demolished without much opposition.

fig 5:

Skyscrapers

Over the centuries, religious laymens and others have tried to compete with each other by building higher to show their religious, civic or economic power. Architects have been hired by municipalities to design the tallest and most beautiful churches, to illustrate God’s – and the respective town’s – power. In San Gimignano in Tuscany the number of towers reached seventy of which only thirteen are left. Rivalling rich families showed who really was in charge in building them. These towers also had a practical reason to exist, in these first skyscrapers expensive tapestries were dyed and kept safe from the sun and dust. The first skyscraper was built in Chicago in 1884, the ten storey Home Insurance Building, and New York propelled rising capitalism further. In the 1930s, there was a real building frenzy between the new captains of industry, some of whom went very far to win the competition for tallest building in the world. Take William Van Alen, the architect of the 319-metre-high art deco Chrysler Building. Van Alen had wanted to put his rival, Morrell Smith, architect of the city’s tallest building, Bank of the Manhattan Company Building, in his place. No one realised what was up Van Alen’s sleeve as he began building. Once finished, he mounted a 185-foot spire, and in just an extra ninety minutes made it the world’s tallest skyscraper. Van Alen’s victory, however, was short-lived as eleven months later in 1931 the Chrysler’s height was surpassed by the Empire State Building. The Bank of the Manhattan Company Building now houses the Trump Building, ironically confirming a somewhat more sophisticated way of showing whose biggest. In the East, Joseph Stalin wanted Moscow’s skyline to reflect the new communist paradise as model for a perfect society, and in 1953 completed the seven towers known as the Seven Sisters. Later on, Asia would take the cake, now in possession of the most skyscrapers, the cities beating each other’s records: Shanghai, Shenzhen, Seoul and Kuala Lumpur. Dubai, with its skyline erected faster than any other wins the game with its stunning 828-metre Burj Khalifa.

Some towers even push the phallic similarities or go for other dubious shapes. The Ghurkin is the catchier name of 30 St Mary Axe, yet, they could also have come up with a less prosaic nickname. Or what to think of the Torre Agbar, the 466-foot building Jean Nouvel constructed in Barcelona? Most – twisted – minds might see a gigantic flashy illuminated dildo in it. Nouvel’s explanation was a bit different, though, referring to the nearby Monserrat’s mountainous peaks which sounds somewhat less convincing. But Nouvel should not worry too much. It can always get worse.

Just have a look at the animation movie of fireworks on top of the Guangxi New Media Centre building in China…

Oscar Niemeyer

fig 6:

Art Nouveau

Though the shape of a skyscraper can be perceived as phallic, few architectural styles are as erotic as Art Nouveau, the building style around the turn of the 19th century that was particularly popular in Belgium and France, and its Jugendstil variant in Central and Eastern Europe. This period is often associated with decadence and longing, femmes fatales. Think of Gustav Klimt, Henri Toulouse-Lautrec and especially Alphonse Mucha. Their work emanated an attraction to – and at the same time, a fear of – the female body, with representations of the vagina dentata or the Madonna-whore complex. Though harder to translate into a building, art nouveau, with is sinuous curves, might originally refer to the organic forms of flowers and plants, and one might recognise fragments from the voluptuous lines of the female body. The defenders of Art Nouveau were freethinkers, often freemasons, who believed in advancing a new society through industrial and social progress. The architectural style had a political or ideological dimension. It should come as no surprise that the Catholic Church was not a fan of the style. The curved lines were regarded as too erotic. The Church responded with an offense, promoting neo-gothic style and a return to an idealised past. The erotic curves are of course not limited to Art Nouveau. It is also present in Oscar Niemeyer’s Brazilian modernism, as illustrated in the following quote from the architect: ‘Right angles don’t attract me. Nor straight, hard and inflexible lines created by man. What attracts me are free and sensual curves. The curves we find… in the body of the woman we love.’

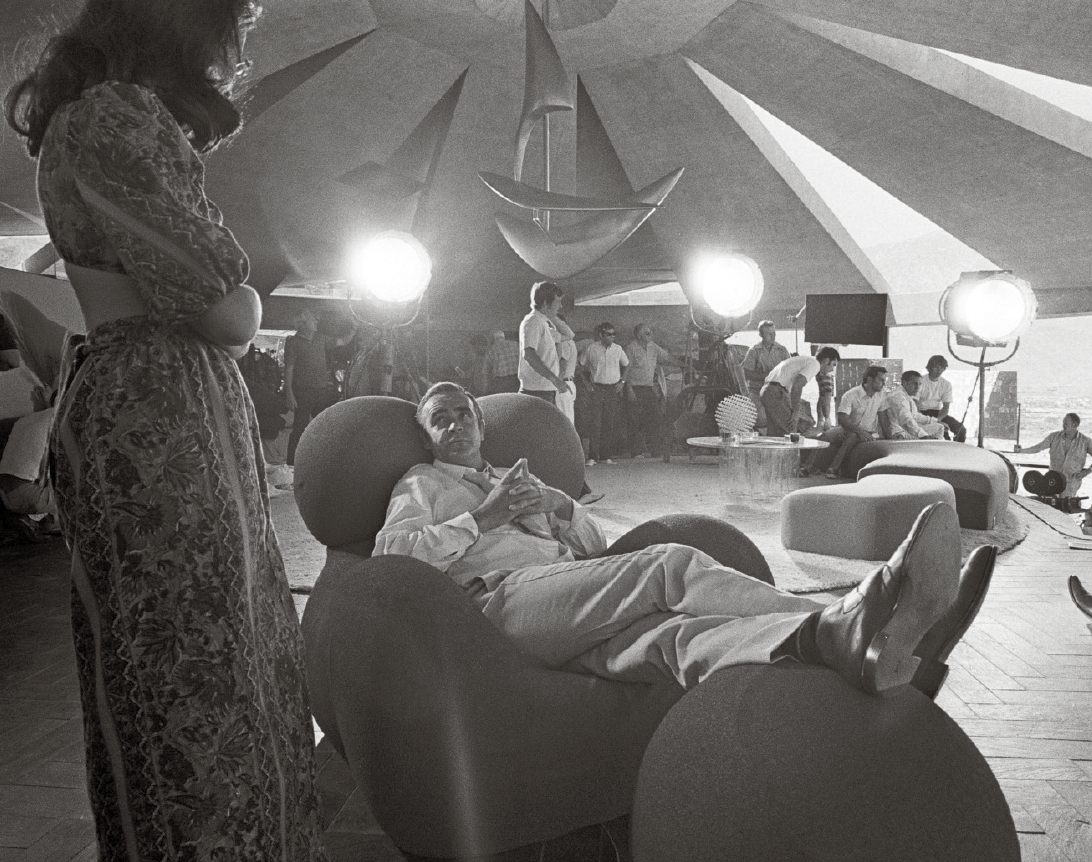

Actor Sean Connery relaxes between takes on the set of the James Bond film Diamonds Are Forever in 1971.

Photo Anwar Hussein

fig 7:

John Lautner

Niemeyer’s buildings are sensual and erotic. The architect had a healthy appetite for female and architectural curves. Most buildings are hardly erotic, including those in which pornographic or erotic movies are filmed, which tend to go for nondescript architecture with generic design. Every now and then, they are shot in a villa with a pool, where part of the action takes place. The settings are mostly as uninspired as the scripts. Exceptions to this are films filmed in houses designed by John Lautner, the Los Angeles-based architect who studied under Frank Lloyd Wright. With their stunning views, sexy curves and play between inside comfort and outside lusciousness, film-makers often use them as the villains’ lairs. Lautner’s futurist Elrod House (1968) in Palm Springs, for example, was featured in the Diamonds Are Forever (1971) scene in which James Bond (played by Sean Connery) is attacked by two stunning yet lethal women in bikinis, Bambi and Thumper, who throw him into the indoor-outdoor infinity pool. With its dramatic, concrete petal dome roof, the villa has brutalist touches and seems to be embedded high up in the Palm Springs cliffs.

Lautner’s Chemosphere (1960–1961s) is a retro-futuristic villa with an octagonal design, supported by a single concrete pillar and diagonal steel arms, high up in the Hollywood Hills. It is only reachable by a funicular, and has been immortalised on the big screen. Nicknamed ‘the flying saucer house’, the villa was bought by publishing mogul Benedikt Taschen, and played a crucial role in Brian De Palma’s Body Double (1984), a B-movie interpretation of Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954) as a watchtower where the protagonist, a peeping Tom, witnessed a (staged) murder. Even more popular is Lautner’s Sheats-Goldstein Residence (1961–1963) in Beverly Crest featured in Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle (2003) as well as Bandits (2001) with Bruce Willis and Billy Bob Thornton. It is perhaps most famously the home of the pornographer Jackie Treehorn in The Big Lebowski (1998). The villa, with its triangular roof, red lounge furniture, the illuminated pool and surrounding room with floor-to-ceiling offering a stunning view of the Hollywood hills, literally screams porn. It was also used for the porno Unleashed (1996). It features girl on girl action on one of the long, red sofas and another scene with one of the protagonists giving herself a go with the stunning view of LA in the background. Just like you have architects’ architects, you seem to have pornographer’s architects. And Lautner is definitely one. Not sure he would take that as a compliment.

Living room of the Eero Saarinen-designed Miller House, complete with conversation pit. Columbus, Indiana, circa 1957.

Photo Balthazar Korab

fig. 8:

Conversation Pitch

Conversation pitches scream sex the same way as Lautner’s buildings. The sunken rooms are usually designed in the shape of a rectangle or circle. They were the essence of cool modernity at cocktail parties in the fifties and sixties and functioned as a kind of shelter to have intimate conversations. They clearly had a social appeal too: not just for talking, boozing and schmoozing, but also for board games with the family on those tamer nights. The architectural art of gathering in smaller groups recurs in similar constructions among other societies over time. The kang in China is a remote sitting area for a group of people that also incorporated a bed and heating intended for general living, working, entertaining and sleeping in the winter. The estrado in Spain is a raised dais covered in rugs and cushions, a remnant of Muslim culture present during the Middle Ages.

The most famous conversation pitch was designed by the Finnish-American architect Eero Saarinen, conceived for the villa of industrialist J. Irwin Miller in Columbus, Indiana in 1957. The Miller House feels like a typical modernist villa. It has a big, open living room painted a pristine white. In the middle of the room, there is a sunken island with bright red upholstery in the shape of a rectangle. You can enter the island by steps leading down into the cavity. In the centre of the couch arrangement there is a glass coffee table and perches for ashtrays or cocktail glasses. The red on white contrast almost has a sexual connotation, like sexual organs, reinforcing the idea of intimacy and private moments. Because of the couches, the thick carpeting and cosy atmosphere, these conversation pitches also occasionally led to lascivious behaviour between couples or even groups. Hence, the conversation pitch was quickly nicknamed the fuck-pit, which needs no further elaboration.

Because of its modern touch, the conversation pitch was also featured in film and TV. In Mad Men, the series about the booze-infested adventures in a 1960s advertisement agency, the protagonist Don Draper’s flat in Manhattan unsurprisingly has a sunken living room. Yet like every trend, sooner or later this one disappeared. Its death warrant was already written by Time magazine in 1963 with an article titled ‘Fall of the Pit’, which enumerated some of the flaws and setbacks: ‘At cocktail parties, late-staying guests tended to fall in. Those in the pit found themselves bombarded with bits of hors d’oeuvres from up above, looked out on a field of trouser cuffs, and shoes. Ladies shied away from the edges, fearing up-skirt exposure. Bars or fencing of sorts had to be constructed to keep dogs and children from daily concussions.’ The article went so far as to suggest the owners fill it with concrete and cover it with floorboards! Luckily, there is a golden rule that what is out, will one day be in again. Over the years, the conversation pitch became the subject of rediscovery and re-appreciation. It not only reached cult status, but also became featured in museums. The Sheats-Goldstein Residence, with its lush furniture comparable to that of a conversation pitch, is now part of Los Angeles County Museum of Art collection. And the Miller House is run by the Indianapolis Museum of Art. As such, the conversation pitch has now become canonical design.