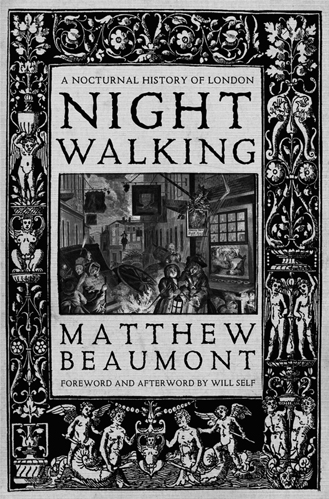

Life brings coincidences, or coincidences pronounce life. I came across Matthew Beaumont’s tremendous research at one of my favourite bookshops in London. Currently wrapped up in thinking about the night myself, and its possible connotations for the one-night-only festival that was about to be unveiled at the beginning of July in London, I was intrigued by the promises of a book that maps the nocturnal history of London over a thousand years, particularly concentrating on the last five centuries. Beaumont provides a genuine insight into the night and its demarcations, through prolific expertise in literature and a literary contextualization of the night, spanning from Chaucer to Shakespeare, Dickens and William Blake.

It is astonishing to discover that nightwalking was an illegal activity, alongside eavesdropping and prostitution, throughout centuries. Night has been associated with expansive adjectives: seductive, uncertain, uncanny, attractive, appealing, con-suming, dangerous and unsettling.

It has been the subject of regulation and control throughout centuries and across cultures. The following conversation is about mapping the night, looking into its inhabitants and the historical evolution of cities where the division between the good and the bad blurs.

Fatos Ustek: How would you describe the appeal of the night and how its seductive forces played a role in your immersion and interest in it?

Matthew:Beaumont: It came about in two ways. The first was, I suppose, a professional interest, and the second a personal interest in the night. The professional interest was aroused as a result of many years teaching various novels and poems in my job, my day job as it were, in the English Department at UCL. I noticed that lots of the writers who I was most passionate about, most enjoyed teaching, wrote about the night in ways that I felt had been overlooked by the existing critical literature, by the existing accounts of English literary history. And I noticed that several of them, if not all of them, were people who went out and walked in London and then indeed in other places at night. And they did so in order to explore various things, which we can discuss in more detail if you like … but that made me think maybe there was a certain revisionist history of English literature to be written, about the nightside of literature, which I felt had also been neglected and overlooked in the existing critical accounts, histories, etc. And then there was this personal interest in the night, since my late teens, probably. I grew up in London; I’ve liked walking at night, and while I was researching the book, I did a lot of walking at night in Paris and in other places as well as in London. And so I wanted to transmit to the book something of the atmosphere of London at night from my personal experience, even if it was going to end up rather abstracted and displaced in the form of an academic book. I wanted to bring that personal interest in the night to bear on the book, even if I didn’t explicitly write in an autobiographical way. I mean, the prefaces are slightly autobiographical and then the afterword is also autobiographical. So there is this little bit of that personal dimension in there. Although not as much as I might have hoped.

Even though we are being encouraged to think that we live in a 24-hour city, there is something residually, vestigially uncanny about the city at night.

Fatos: You introduce a historical tra-jectory about how night has been assigned different connotations. Perhaps if you could start from a general set of attributes; it is like the night is a place where the invisible becomes more powerful than the visible; we can attribute many lexicons such as the unknown or the stillness that constitute the landscape of the night.

Or it is a place of uncertainties that can evoke danger, potential violence as well as intrigue or witnessing other people’s ways of being. We could also go into detail, elaborating different ways the night is regarded or controlled, but what did you want to explore the most? Would you say that the night has a feminine connotation? Could you perhaps share with us what night evokes for you?

Matthew: What night most evokes in me, is, I suppose, a sense of the uncanny. It is a familiar concept and has been for a long time because Freud wrote about it in 1919; but it is not the [uncanny that] I use explicitly in the book. I was looking at the city in the night as an uncanny phenomenon. I was trying to explore the ways in which, at night, at nightfall, the city becomes unsettling and intriguing at the same time, which is to say, in terms of what Freud sets out in his essay: everything that is, or once was, familiar in the day becomes subtly strange in the night under the altered social circumstances, in altered optical conditions of the night when darkness falls, when artificial light emerges. So what I wanted to do was analyse that sensation in terms of the way in which writers over the centuries have tried to evoke it or represented it. It seems to me, living in the city, it is at least partly lit at night by LED lights (which are unbearably bright, I think) that completely expel the mysteriousness of night from the places where they are used. Even though we are being encouraged to think that we live in a 24-hour city, nonetheless, there is something residually, vestigially, uncanny about the city at night. And this brings me onto, I suppose, the question of what I wanted to do with the book. One of the things, certainly, centrally, that I wanted was to reconstruct the history of, as I see it, the protagonist of the city at night in its thousand-or-more-year history, certainly since the Middle Ages: this figure of a nightwalker, the person who inhabits the night at least in part because they don’t feel at home in the city in the day – because they don’t inhabit the city comfortably in the day. I was interested in that figure, which for thousands of years has been a vagrant figure. I mean, originally, in the Middle Ages such a figure was identified as a vagrant or a prostitute, but today still they would be a vagrant in the sense of homeless people whose population we have seen exploding over the last few years onto the streets of London, as in other cities, in fact, that have been subject to the economic crisis that we’ve experienced over the last ten years.

Fatos: Could you perhaps give an example from the Middle Ages context?

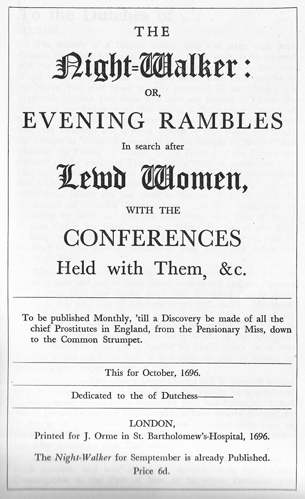

Matthew: John Dunton’s The Night-Walker: Or, Evening Rambles in Search after Lewd Women, with the Conferences Held with Them appeared in 1696, roughly a decade after public lighting was first introduced in London. The Night-Walker comprised a series of tracts against whoring and whore-mongering among the metropolitan nobility. It was inspired in part by anxieties about the degeneration of aristocratic bloodlines. Dunton is a splendid embodiment of the contradictory but symbiotic relationship between puritanical impulses and satanic ones in the nocturnal city. The moral kicks he got from the streets at night cannot be extricated from his sexual kicks. In him the night-watcher and the nightwalker were in an uncomfortably close relationship.

As the historian Joachim Schlör remarks of the ‘missionaries’ who patrolled the nineteenth-century city at night, ‘they too “penetrate” into the nocturnal city, they too seek the extraordinary experience, they too participate in the cycle of chance encounters, they too see how far they can go.’1

Facsimile of the title-page to the October edition of The Night-Walker: Or, Evening Rambles in Search after Lewd Women, with the Conferences Held with Them

Fatos: We could perhaps explore this idea of security and relationship to power, but what I was intrigued by was the situation of the nightwalker that you map through different accounts; the nightwalker could have a wealthy background, an aristocratic background, and so has a different way of relating to the city at night as well as in the day.

Matthew: Middle- and upper-middle-class men, those I have identified as noctambulants, were of course far freer in their movements at night than women. In the eighteenth century, as in the nineteenth, ‘the suspicion of prostitution fell upon women who were about at night unaccompanied and without justification’.2 Picaresque accounts of the streets at night in the eighteenth century are therefore predicated on a male subject, one that is physically mobile and, more often than not, both patrician in his attitude to the poor and patriarchal in his attitude to women.

The partial exception to this rule, which in the end it probably reinforces, is The Midnight-Ramble: or, The Adventures of Two Noble Females: Being a True and Impartial Account of their Late Excursion through the Streets of London and Westminster (1754). This intriguing fiction, published by an anonymous author who is presumably male, features two gleeful female protagonists that explore the streets of London at night in disguise.

The narrative opens with an account of the reasons for the heroine’s social (and perhaps sexual) frustration. Lady Betty, a virtuous young woman, has been married off to Dorimant, a dissolute nobleman who spends ‘his Evenings in riotous Mirth and Debauchery at the Taverns; and most commonly pass[es] the Remainder of the Night, in the Arms of some courtesan at a Bagnio’. She befriends Mrs Sprightly, the wife of Dorimant’s best friend Ned, and the two women resolve to disguise themselves as monks in order to monitor their husbands’ nocturnal activities in the city. In prosecuting this plan, they commission their milliner, Mrs Flim, whose name signals that she is adept at idle deception, to bring them ‘ordinary Silk Gowns, close Capuchins, and black Hats’. And, having taken care ‘to exhilerate their Spirits with a Bottle of excellent Champain’, the three of them set off in pursuit of the men.

After spying on their husbands at the playhouse, the three women are frustrated in their attempt to follow them by coach to a tavern at Temple Bar because there are so few vehicles on the street. Instead, though it is past 10 p.m., they determine ‘upon following their Chace on Foot, at all Hazards’.3 At a spot between Somerset House and the so-called New Church on the Strand (St Mary le Strand), they meet ‘four Street-Walkers, that had been long used to tramp those Quarters’. These prostitutes assume that, because of ‘the Oddness of our Ladies Disguise’, Lady Betty and Mrs Sprightly are ‘some Strangers of their own Occupation, that were come thither to trespass upon their Walks’. So they jostle and curse their rivals.

…they were going from one party to another, from one ball to another, from one gaming table to another…

Fatos: There is kind of a reciprocation of the nightwalker, as you said: the one who can’t fully belong to the day and its goings-on; and the nightwalker who actually suffers from insomnia or some kind of unsettlement within his ontological manifestation. Could you perhaps elaborate more about this idea of the nightwalker? What is it that he is after? I would assume that there is this relationship of desire, a need or a form of satisfaction fulfilled through being out on the streets in the night.

Matthew: One way of approaching it would be to cite a line that I quote in the introduction to the book, a line from 2666, the wonderful novel by Roberto Bolaño, the Chilean novelist. He refers in passing to people inhabiting the night, either having time to burn or running out of time. And my point in quoting him, is to say that, actually, the kind of people who inhabit the night really experience both states at the same time; that the kind of people who walk in the night loiter in the night, are those who both simultaneously have time to burn and are running out of time. And that’s the paradox, if you like, that I am trying to explore and dramatize in my book. The neglected, overlooked, forgotten inhabitants of the modernizing city ever since the Middle Ages have been those who find a kind of home in the night because they, one way or another, are either materially or spiritually homeless in the day, and at the same time have lots of time on their hands; they can loiter, they can walk back and forth across the city with no apparent commitments. But they are also in some way running out of time, they are … clock ticking against them; the world is against them. They are on the kind of path of destruction, or distinction. There are lots of noir novels and noir films in the twentieth century that feature this kind of character. For example, the central character in Night and the City, a novel by Gerald Kersh and then a film by Jules Dassin, has all sorts of time to loiter around and chat with other more or less criminal or petty criminal types in the streets at night in Central London, but at the same time he is on the run, he is being hunted down, his time is up, and that is very much a characteristic experience of the nightwalker. Not just from the bottom end of the social scale but among bohemians, relatively privileged types being out of time and having too much time. As you rightly implied, there are various different social strata of nightwalkers. At the very bottom in the Middle Ages we’ve got the common nightwalker who is criminalized in the late thirteenth century, if not earlier, by a law known as the Nightwalker Statute: anyone breaking the curfew was liable to be rounded up by the Nightwatch, which was the primitive form of policing in London right until the early nineteenth century, and they could be imprisoned or even deported. So there is the common nightwalker, but there are the various other kinds, perhaps including the Nightwatch himself, who was also someone who had to walk and to patrol at night, and who was also often a semi-criminal type. Then there are the more middle-class nightwalkers who I refer to in the book as noctambulants rather than noctivagants. The noctambulants are those who are much more like the flaneurs; the famous flaneur in Baudelaire’s poetry and prose ambles about the city at night in a relatively leisured way, sucking in its life; perhaps exploring it in literature, or in some cases they amble about the night or go out into the streets at night in order to save the vagrant population of the city; to save the prostitutes, or to save the homeless people from perdition, perhaps by Christianizing them, by evangelizing to them. Then there is, as you also said, the aristocratic types who even in the Middle Ages had free passage through the city at night. Because of their privileged status they were given a pass by the nightwatchmen who were exempt from the rules, unlike the noctivagants or common nightwalkers, increasingly treating the city at night as a source of sociability, going from one party to another, from one ball to another, from one gaming table to another. The class stratification of society at night is particularly clear, I think, and that is one of the things that excites me about the night: paradoxically the darkness illuminates society in unexpected ways. One sees the society in relief, in particularly interesting light and in a kind of chiaroscuro effect that isn’t available in the day.

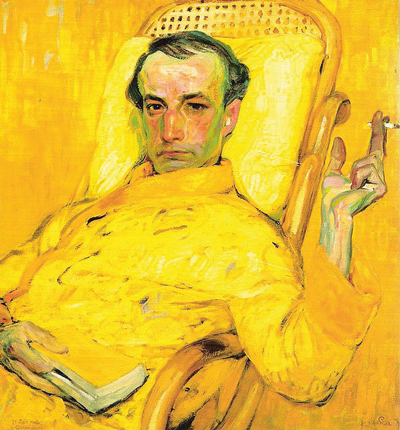

Portrait by Frantisek Kupka, a Czech avant-garde painter living in Paris, of Charles Baudelaire, the French decadent poet, based on one of Nadar’s daguerreotype photographs.

Fatos: Could you open it up a little bit? What do you mean by that?

Matthew: I suppose I mean that there are class divisions, but there are also gender divisions, and ones in terms of race are particularly visible in the darkness. So one’s social status is historically very much apparent at night in a way that it isn’t so much in the day among the pressive bodies where everybody appears to have their business to do and places to go. Things to get up to. Gender divisions are particularly acute, more acute even than the class distinctions at night. I mean, women historically, of course, have simply not had access to the city at night in the same way that men have. They don’t have what I call a right to the city at night, they haven’t had a right to the city at night historically because it’s been potentially so dangerous for them. The night renders them vulnerable either to forms of harassment or to abuse or to assault or to criminalization as sex workers. Although some men from the working class have historically been vulnerable in the night, that vulnerability is nothing like the vulnerability of women historically at night. In the twentieth century, black minority men and women in the night have been even more susceptible to criminalization and marginalization. It has been assumed that they are conspired against in some ways or they are criminals in some way, and ‘stop and search’ has been particularly aggressively used. For example, young black men at night – and it still the case in America today as well as in Britain – have been prone to multiple incidents over the last few years, as the Black Lives Matter campaign testifies: with curfews being imposed in supposedly advanced cities in the most powerful nation in the world, going right back to these medieval forms of policing.

Fatos: Yes, exactly. I was very much intrigued by the kind of reciprocation of the three illegal acts that were commonly regulated, or committed/punished: nightwalking, eavesdropping and prostitution. It is interesting to think about how the initial concept of the city started to emerge with the subject who actually works, how the night needs to be even more controlled. Could you perhaps talk us through this historical trajectory?

Matthew: Perhaps it is best to start with the Middle Ages and the legal construction of the night, if you like. I suppose the most important initial point is the curfew, the introduction of the curfew in 1068 by William I (William the Conqueror) only a couple of years after he did conquer England. So he introduces the curfew ostensibly in order to avoid conflagrations in the night, and in order to stop fire spreading through the city and destroying it; it has happened, of course, spectacularly in 1666. The word is derived from, a corruption of, the French word couvrir le feu (cover fire) but it was also clearly a way for William I of policing, pre-empting political conspiracies in the aftermath of his invasion, and that in some ways set a tone for the policing of the city at night thereafter. There was always a political dimension to it, I think, to the control that was exerted by the curfew and the control that was exerted by the Nightwatch, as it was later instituted. So the curfew becomes a means not only of pre-empting conspiracies but also policing population and of trying to keep the riff-raff off the streets. In the late Middle Ages, under the impact of inclosures in the countryside – which really is the emergence of capitalism in its agrarian form – thousands and thousands of migrants, of migrant labourers from the countryside, former peasants, came to London and other cities looking for work, and there wasn’t enough work, and many of them became vagrants, many of them became homeless, had to beg and had to sell their bodies if they were women. This expanding population had to be policed and to be marginalized, had to be anathematized, and the Nightwatch and these nightwalker statutes, from at least the thirteenth century on, were used to do that. At the same time, thinking further about this context of early capitalism, there was increasingly an insistence on an ideology of productive labour in the day, which made night-time activity seem completely unacceptable. And that runs right through to the eighteenth and nineteenth century and arguably to the present. There was an emphasis on daytime people being good, healthy, productive, contributing to society and to the economy, with night-time people being those who more or less flagrantly refused that logic, that logic of the Protestant ethic, spirit of capitalism, etc., who by staying up all night for whatever reason and sleeping in the day were placing themselves consciously or unconsciously outside of the disciplinary regime of capitalism as it was emerging … Still today, those who sleep in the day and go out at night are really seen as sort of insurrectionaries, in that they inverse the order, the benign order, supposedly benign order, of a productive capitalist economy.

The main character in Gerald Kersh’s novel Night and the City is, more than anything else, Soho – London’s seedy, sinister underbelly. It is, literally, the dark side of the city – most of the scenes take place between dusk and dawn. Kersh clearly knows the world he describes very well – some of the best passages in the book are those about the people who flow through the bars and back alleys. The story focuses on Harry Fabian, a petty thug who lives off his prostitute girlfriend’s earnings. From the outstanding opening sequence, it’s clear that Harry is a blusterer, who fools no one except the hopelessly naive, and those who want to be fooled by the promise of easy money. The novel was first filmed in 1950 by Jules Dassin, who had directed The Naked City two years earlier. The film was made in Britain, and the setting remains the London wrestling world. The movie starred Richard Widmark as Harry Fabian and is often thought a significant London film noir. The film was remade in 1992 with Robert De Niro playing the lead role. It was directed and produced by Irwin Winkler. The setting of the film was changed to the New York boxing world, and Harry Fabian is a lawyer. The film draws predominantly from the Dassin film rather than the source novel.

Fatos: Because it is not only the mind that is disciplined or regulated but also the bodies in that sense.

Matthew: Yes, a body that goes to bed early, sleeps more or less through the night and gets up at dawn to go and work, from the Middle Ages onwards, is a productive body in terms of the economy, and it is a body that is reproductive as well in reliable and legitimate and acceptable ways. The reproduction of society through the generation of people as well as the generation of wealth is secured and guaranteed according to the official intensifying capitalist ideology from the late Middle Ages onwards. It is a good society, a positive community, and those who lie around in the day and venture out to the streets at night are overturning that.

..Association of the night legal or illegal, with primitive forces and darkness and legal associations of criminality heightens the erotic dimension of the night…

Fatos: If you were making an analogy, it is like the night brings a blanket of darkness onto the city but society and the rules of governance add another blanket. We trace back to the Industrial Revolution and labour becomes equated with identity, with efficiency; your life equates to your work or your laborious engagement with being. Then perhaps nightwalking in that sense could be a revolt, a kind of disobedience. This is not about fitting the norm; it is actually claiming a separate space because you are still inhabiting the same streets or you are still relating to the buildings or to the regulated infrastructure of the city as it is also active in the night.

Matthew: Night, certainly in the Middle Ages, and arguably still to some slight extent, is associated with the powers of darkness, with something or with some things, with phenomena that are extra human, superhuman, subhuman… However, we want to describe them and they are totally other to society as it’s laboriously constructed and maintained, and one of the things that the legislation and the policing of the city has done historically is to identify people who are forced for one reason or another to inhabit the night, or who choose to inhabit the city at night. It identifies them with the spiritual, the ontological, the metaphysical, with the ghostly, with the spectral, with the evil, with all those primitive or even primal forces and energies that disrupt the rational operation of society. That has been a powerful weapon of the state, and of the authorities and the police, for more than a thousand years; that you are somehow associated implicitly with evil if you inhabit the night. To give a generic example from today, in a serial-killer movie, for example, they draw on this ancient or almost mythical identification of the person in the night and on the streets in the night with the primal forces of darkness.

Fatos: Provoking the forces of darkness, could we also talk about the different sensual ways of relating to the night?

Matthew: Night-time entails a different sensorium, particularly in the city, especially when the streets are empty, and especially compared to the daytime. Night-time sensorium eroticizes bodies, there are positive and negative consequences of that. Those consequences are apparent throughout the centuries in London, the positive being that it opens the city out to possibly exciting and potentially intimate interaction. Sexual, bodily interaction of a kind that is forbidden in the day; negative in the sense that it brings into sharp focus the sexual politics of the society that is less visible in the day. A woman on her own on the streets in the night, is a crucial example; she is either potentially a victim or potentially a predator. That kind of stark dichotomous division does not apply in the same way to men at night. The social hierarchies, asymmetry between the sexes based on a predatory sexual paradigm, are particularly inherent.

Fatos: If we think about the erotic as a fluctuating space where visibility makes sense through the invisible, or exceeding the societal regulation … How could we talk about eroticism and its intrinsic qualities, explored intellectually and practically from the perspective of night-time figures?

Matthew: Association of the night legal or illegal, with primitive forces and darkness and legal associations of criminality, heightens the erotic dimension of the night. Going back to the Middle Ages, the category of eavesdropping becomes important, in the courts and the Nightwatch, because both carry with them these vague and predatory associations. Standing outside the house either listening in or looking in on people inside as they are going about their business: eavesdropping is associated with voyeurism and also picking up gossip. There is a clear sense from the Middle Ages of the sexual charge that the night brings.

The Romantics, poets and thinkers of the eighteenth century, of rapidly industrializing cities of Britain and Europe, saw in the night the possibility to transgress the limits of the bourgeoisie family, the limits of home, limits of a cosy, comfortable domesticity and interiority. They were interested in a different kind of interiority, interiority of the self. They were interested in the outsiders of the society, the poor and the neglected. The night introduces a regime that focused ideologically on the family. On one hand Dickens sentimentalizes the family, and on the other he has an acute sense of the corruption of the family, the nuclear ideal of the bourgeoisie family. He, of course, himself relentlessly walked at night, pounding the streets at a remarkable pace, at times crossing thirty miles’ distance overnight, so fast and hard that he started hallucinating. On the other hand, his famous essay ‘Night Walks’ gives ample evidence of the night-time ecology; in this he has makes observations and sketches people, conscious of people at night, loitering or cruising.

1. Joachim Schlör, Nights in the Big City: Paris, Berlin, London, 1840–1930 (London: Reaktion, 1998), p. 260.

2. Schlör, Nights in the Big City, p. 170.

3. Anonymous, The Midnight-Ramble: or, The Adventures of Two Noble Females: Being a True and Impartial Account of their Late Excursion through the Streets of London and Westminster (London: B. Dickinson, 1754), pp. 3, 8, 10.