My first meeting with Kenneth Anger was meant to take place on the afternoon of the 86th Academy Awards. Anger’s assistant and collaborator Brian Butler originally suggested we meet at the Chateau Marmont. It felt like a deliberate and loaded choice to meet on that particular day at that particular location, given Anger’s fascination with Hollywood’s underbelly, rumors and scandals. After I suggested the place might be overrun by the industry and too loud to carry out a conversation, we decided to meet at the newly minted Ace Hotel in downtown Los Angeles.

Anger never showed up. In many respects, I understood the reasons for his absenteeism. Why, for instance, would a canonical filmmaker, aged 87, a celebrity among cinephiles and occultists, have any interest or desire to meet with me? What had he not already revealed in the interviews and recorded conversations that have spanned his six decades long career? I felt burdened by Anger’s long history and prolific career, so I assumed maybe he had started to feel the same way and had lost all interest in the interview as a result.

We were eventually able to meet just over one month later at Musso & Frank, a historic restaurant and bar that has been open in Hollywood since 1919. It’s a place that is consumed by the look and feel of the movie industry’s Golden Era; a relic from a bygone period that remains noticeably untouched. In the months leading up to the interview, I read a conversation between Anger and artist Alex Israel that had appeared in the pages of Purple a couple years earlier. When the two artists sat down to talk, Anger ordered a chicken potpie. Our meeting, though, was between meals, as it was just after the lunch hour and Anger ordered custard and a coffee.

Aram: We had planned to meet once before on the day of the Academy Awards, which would have been so perfect and surreal in many ways. If our meeting were to take place at the Chateau Marmont, for instance, the interview would have had a certain glow or aura around it.

Now that we’re meeting here on an average Saturday in April, at Musso & Frank in Hollywood, it hardly makes sense to ask a question like this, but would it have felt the same for you? Do you think about the industry in this way, as having some kind of aura, or power of attraction? Is there any significance to the way you think about your own relationship to the industry, as either an outsider or an insider?

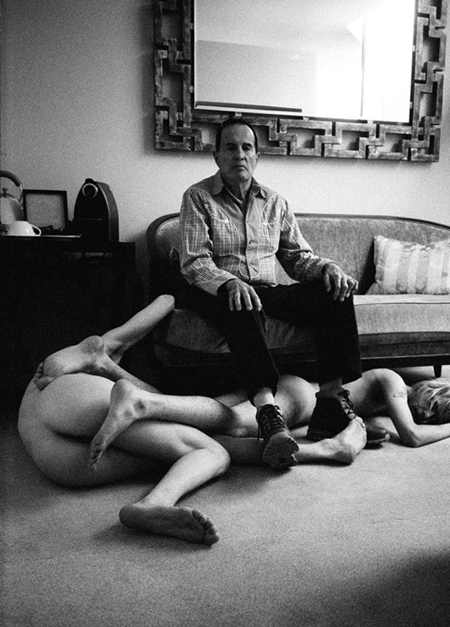

Kenneth Anger Portrait © Matthew Stone 2010

Kenneth: Well, I’m a bystander, an interested observer of Hollywood rather than a member of working-class Hollywood. But I grew up here and I’ve been a friend of a lot of people that work in the industry. And I’ve seen its ups and downs. I went to Beverly Hills High school and my best friend was Harry Grant Jr.; Harry Grant was the production manager of Fox. If I wanted to, I would have started by working in the mailroom or something like that since that’s the usual way of starting in the industry. But something unpleasant happened at that time, which put me off of working in Hollywood. The ridiculous ‘red scare’ and friends of mine were intimidated by it.

I was a good friend of the Jack Cole dance group and they worked on a lot of the Columbia musicals. They had a chance to appear at the Lido in Paris, the city’s leading nightclub, so I joined them abroad. That was the beginning of a long period spent in Paris. I met Henri Langois at the Cinémathèque Française where I worked and helped identify the original titles to a lot of silent films that he had. He didn’t know the original titles so I did the detective work for him.

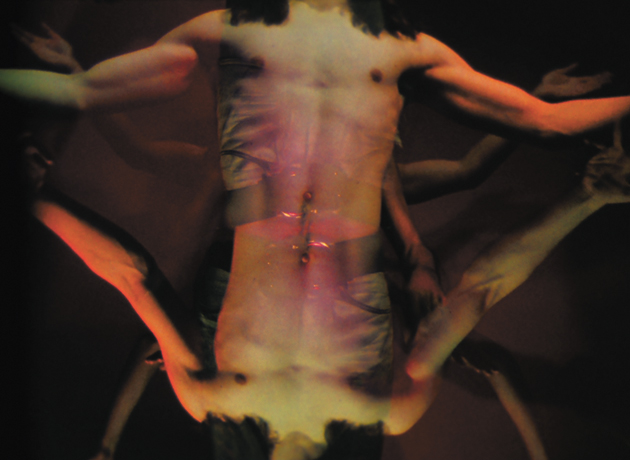

Invocation of My Demon Brother (1969) is an 11-minute film directed, edited and photographed

by Kenneth Anger. The music was composed by Mick Jagger playing a Moog Synthesizer.

It was filmed in San Francisco at the Straight Theater on Haight Street and the William Westerfeld

House (the former ‘Russian Embassy’ nightclub). According to Kenneth Anger, the film was assembled from

scraps of the first version of Lucifer Rising. It includes clips of the cast smoking out of a skull,

and the publicly filmed Satanic funeral ceremony for a pet cat.

Aram: When would that have roughly been?

Kenneth: That was in 1950. It was a great time to be in Paris and I got to meet people like Jean Cocteau. I met quite a few of the famous people who I respected and whose work I knew of. I wanted to meet Andre Gide, but he had just passed away when I was on the boat to Europe.

Aram: By that time you had already made Fireworks (1947), do you know if it had already been screened in Paris prior to your arrival there?

Kenneth: Yes, it was shown at the Cinémathèque Française.

Aram: Were you as known in Paris as you knew the city before you arrived? Were the people you met there as equally aware of your work?

Kenneth: I suppose, yes. I was a filmmaker.

Aram: Many of the stories of your early interest in filmmaking start with your teenage years. Where did an interest in moving images, a fascination with film originate for you?

Kenneth: Well I’ve always been intrigued by film but I wanted to use it myself as an artist, more like a painter; the material rather than the narrative idea of film. My family had a 16 mm camera that was used primarily for holidays and vacations and most of the time it was just sitting there. 16 mm film was something that slightly affluent middle class people had at that time to record their families, and I thought that artistic work could be done with a 16 mm. I began using the camera to make short films. I made several short films before Fireworks, a film I made on hearing there was a festival in Biarritz, France called Festival du Film Modi (the Festival of Cursed Films). I just shot it and mailed it to them. They showed it and it won a prize, which was just a symbolic thing, but it was encouraging nevertheless. I was just graduating from Beverly Hills High School at the time.

Basically sex is just one of the things I’m interested in…

Aram: The early films, the ones that preceded Fireworks, which I’ve read have all been lost – do you consider them works? Or do you consider them something else?

Kenneth: For one thing they were all shot at sixteen frames per second, and you need twenty-four frames per second if you’re going to put a soundtrack on the film. So that’s one of the reasons I never released them. If I wanted I could release them on video, not film, which I may do someday.

Aram: Are those films rooted in the same interests that informed your filmmaking since then? I mean, would you consider the early films as works because there seemed to have been an ongoing conversation – maybe it occurred a handful of years later through figures like Stan Brakhage and others – about amateur versus professional modes of filmmaking.

When you say that you started by using your parents’ camera as a teenager, I wonder if there was any attempt on your part to conceptualize the use of this readymade medium. Until that time, it would seem that there was little experimentation that could have informed your approach to narrative.

Kenneth: There is a tradition of experimentation or avant-garde film-making that goes back to the 1920s. There were a few artists working with it in that way. Not only in France but a few people in the United States. I began by always thinking of the film as a tool of personal art rather than something commercial.

Aram: A lot of the writing and scholarship on your work tends to play up your fascination with the so-called Golden Age of Hollywood, to ritual, to a form of early music video, to a kind of depiction of gay male sexuality, but I wonder how you feel about it all now? We talk about Fireworks as if it was made yesterday, but it was made almost sixty years ago.

Kenneth: Time flies.

Aram: And in some ways it would seem you’ve resisted time. For instance, you’ve returned to some films many years after their so-called completion to pair the images with different soundtracks. How would you characterize the resuscitation of past works?

Kenneth: It’s because I’m an experimental artist. I’m intrigued by the way the films would go to different places using different music.

Aram: Where were some of the places those films would go?

Kenneth: Well, they would just gradually give an impression of something else.

Marianne Faithfull as Lilith in Lucifer Rising (detail), 16 mm, color, 27 minutes, 1981.

Aram: How do you feel about the reception of your work through time? To your mind, is there anything that hasn’t been said or that has been overlooked?

Kenneth: I don’t pay a lot of attention to what people write about me. If there’s some great misunderstanding, then I’ll write them a letter, but usually I’m pretty happy with the kind of writing that’s been done about me.

Aram: And what do you think about the interview format? Without getting too self-referential, I’m probably asking you questions that you’ve been asked countless times before. Have interviews grown tiresome to you?

Kenneth: No, I don’t do them often. And it’s always a slightly different perspective with a different person.

Aram: I’ve recently read that you were at one time working on a third iteration of Hollywood Babylon, but that you haven’t felt comfortable releasing it. What’s the scope of the unpublished volume?

Kenneth: I’ve roughed it out, but there are several subjects I wanted to write about who are still alive. It’s easier to write about people when they’ve passed on; ghosts don’t sue.

Aram: What was it that attracted you to these people in the first place? I ask because I would think that the Hollywood of today would be far less interesting and scandalous as the periods covered in the first two volumes of Hollywood Babylon.

Kenneth: he period from the silent era to the 1960s is what interests me. I don’t find anybody in the current crowd – actors, directors, or whatever – to be fascinating. They’re competent actors and so forth, but I’m interested in what is in the past.

It’s not that bad, really; all you have to do is turn out the lights…

Aram: But would your research bring you into the present in some way, I guess through the people who are still alive?

Kenneth: Originally I didn’t pursue it because it would have triggered some impossible trouble and I didn’t have the resources, the lawyers and all that, to fight them.

Aram: What would the nature of the trouble been?

Kenneth: Well, I really can’t say.

Aram: How did the research methods change from the earlier versions to the one you haven’t released? Your research before would have been with historical or archival materials and I’m wondering how would you go about researching the gossip of today, of the present? What are your sources?

Kenneth: I Keep my ears open. I just don’t find the present to have enough fascinating material to make for anything that is worth it, so I will work on volumes one and two and that’s going to be it.

Aram: You are commonly referred to as an icon of ‘underground’ filmmaking. Did you ever see any significance to this brand identity? Today, do you consider the idea of an underground as a viable possibility?

Kenneth: It’s just the journalistic conundrum. At the time, even when it was new, I didn’t think the term had much validity. But there were a number of people who were working independently like me, and I think it was Newsweek to put a label on it in an article.

Aram: In the early 2000s you began to exhibit your films in the context of museums and galleries. What was the impetus behind this shift, and what was the interest for you to start showing in galleries rather than in traditional cinema contexts?

Kenneth: I consider my films works of art that are related to other art. Besides, they wanted to show them so I was quite happy that I was showing in galleries.

Aram: That’s right, but the question is not so much about whether they are artworks or films. It is more a question about the physical experience of moving images in a gallery as opposed to a movie theater, where, for instance, the viewer is enveloped in total darkness with soft velour seating and armrests. Galleries can be clinical at times and generally inhospitable to film and viewership, having hard benches, acoustical challenges, an inability to tether a viewer’s attention to narrative.

Kenneth: It’s not that bad, really; all you have to do is turn out the lights and put up a screen. It’s not an impossible situation.

Aram: One thing that has been lost on our conversation was any mention of erotic tendencies within your films, but I wonder to what degree sensuality and a sensuousness of images was a priority for you?

Kenneth: I was a friend of Doctor Kinsey and he interviewed me when I was a teenager for his book, so I’m actually part of the statistics. His graphs and things like that were so cold and non-sensual in their presentation, but he was a fascinating man. He interviewed me for about three hours and then I arranged for other people my age to come in and be interviewed by him. At the time, he was collecting images that were part of the history of male sexuality; he did one book on men and another on women.

Aram: How did he find you?

Kenneth: I had a screening of Fireworks at the Coronet Theater, and he was at the midnight screening. He introduced himself and said he’d like to interview me and also to purchase a print of Fireworks for his institute. That was my first sale.

Aram: Did he give you any impression or thoughts on what he thought of the film?

Kenneth: Obviously he thought it was of interest for his purposes since the print is still there in Bloomington, Indiana at the Kinsey Institute.

Aram: Perhaps the film was also a contrast to his sterile scientific presentations that you mentioned before?

Kenneth: I’d remove the word sterile. There’s nothing sterile or un-interesting about sex. It’s the human condition that has all kinds of possibilities.

Aram: Are sex or sexuality interests you’ve approached in your more recent films? It seems like these topics have gone in and out of your focus over the years.

Kenneth: I made a couple of so-called private films for the Kinsey Institute but they’re not for the public. Basically sex is just one of the things I’m interested in; I’ve made just as many films that have nothing to do with sex or sexuality.