Kahlil Joseph’s short films are hard to classify. Somewhere between music video and avant-garde cinema, they’ve found audiences in both the art world and mainstream pop culture. It’s a testament to the uniqueness of Joseph’s artistic vision that neither space can contain it. This year, museums in New York and Maastricht will be treated to m.A.A.d, his striking two-channel installation, a collaboration with Kendrick Lamar from 2014, shot in the musician’s home town of Compton, Los Angeles, and featuring snippets of home movies from Lamar’s childhood.

The approximately 15-minute-long m.A.A.d. is set to songs from Kendrick Lamar’s revered 2012 album good kid, m.A.A.d city. At MOCA it is presented as a double-screen video installation with the side-by-side images either supporting or ricocheting

off of each other. If asked what Joseph’s m.A.A.d. is about, the answer is ‘Compton, two decades after the riots,’ but without real dialogue or anything resembling a linear narrative, a more accurate answer is probably ‘a feeling of Compton, two decades after the riots.’ Courtesy The Verge

Most people, however, will encounter Joseph’s work online. Almost all of his music video work can be found there. His widely seen collaboration with Beyoncé, the ‘visual album’ Lemonade, was an undisputed Internet sensation that catapulted Joseph into a new league. He is without question the most sought-after under-the-radar filmmaker around. If his name remains unfamiliar, it’s because he prefers to stand back and let the work speak for itself.

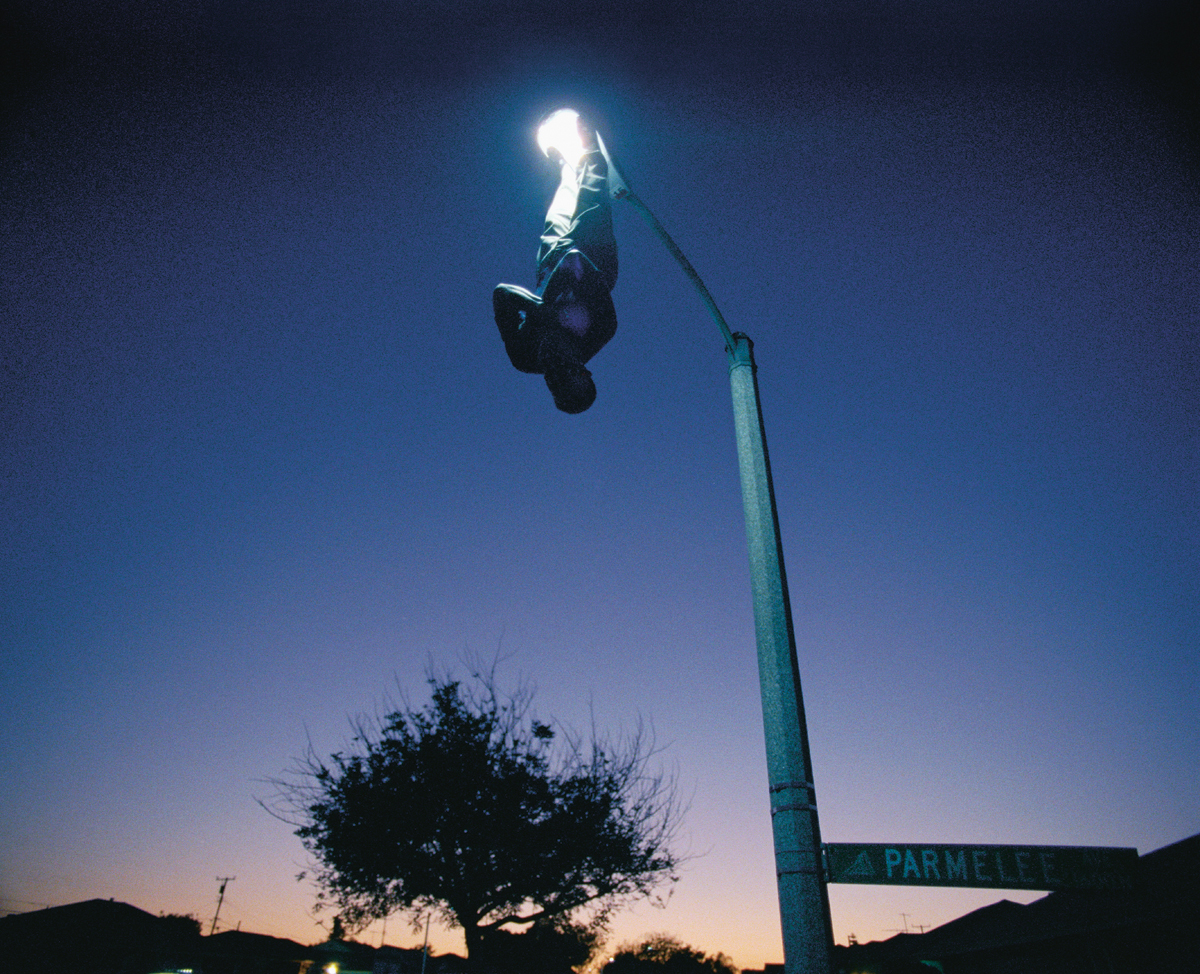

And the work speaks volumes. Joseph’s films, like the music that inspires them, demand to be played over and over. This is because he’s never telling just one story. His films operate on multiple levels simultaneously. On the surface, they offer the seductive pleasures and graphic visuals of classic music videos. Joseph has an eye for rapturous imagery and a penchant for gliding, hypnotic camerawork that transforms banal urban spaces into dramatic stages for kinetic young bodies. It’s easy to stay in this sensual world. But Joseph has a lot on his mind. An avid cinephile, his works are laden with cinematic references. It’s easy to recognize the influence of Andrei Tarkovsky and Spike Lee, among others, in Until the Quiet Comes, a chilling and elegiac short Joseph made with musician Flying Lotus in 2013. It features a young man, shot dead as a result of gang violence, whose body continues to dance into the night, as if resurrected. Joseph endows the gritty backdrop of a Los Angeles housing project and the predominantly black residents with uncommon beauty and respect. Black identity and its representation is something he explores head-on in Belhaven Meridian, a short based on the music of Shabazz Palaces that unfolds in a single miraculous shot that sweeps us through the streets of Watts, picking various characters and micro-narratives. It’s Joseph’s homage to Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep, the 1977 film that heralded the emergence of a new black independent cinema in America. When Joseph’s camera flips upside down, the long shadow of a young man running becomes an image of ecstatic beauty.

The sheer variety and propulsion of imagery contained in a single project can be astonishing, if not exhausting. Joseph’s only feature to date is the 2015 documentary The Reflektor Tapes, a behind-the-scenes chronicle of the making of the Arcade Fire album. It’s best understood as a kind of maximalist visual analogue to the band’s extravagant and grandiose disco-rock aesthetic. Restless, fragmentary, and elliptical, it’s more concerned with evoking the messiness of artistic process than with capturing the thrill of performance, which might account for why the film didn’t catch on. My guess is that it will be rediscovered in coming years.

Perhaps the defining feature of Joseph’s shape-shifting work is its uncanny ability to feel both nostalgic and futuristic. Soft-spoken and thoughtful in person, Joseph sat down for a wide-ranging conversation that touched on everything from Alice Coltrane to Michael Bay to Chris Marker.

Paul Dallas: The last couple of years have been especially busy for you. People outside the art and film worlds may not know your name, but they’ve certainly seen your work.

Kahlil Joseph: I recently saw a docu-mentary called Sky Ladder on the Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang. It’s really dope. He’s such a celebrated artist now that people literally throw money at him and say: ‘Do whatever you want.’ Back in the seventies and eighties when restrictions in China were intense, Cai was making amazing work. The Chinese government invited him to make an artwork for the Olympics. It makes me think of this White Stripes song called ‘Little Room’. Have you heard it?

m.A.A.d. 2012 Courtesy: Pulse film

Paul: A long time ago, but I don’t remember.

Kahlil: It’s a twenty-five-second inter-lude on one of their albums. The lyrics go: ‘Well, you’re in your little room / And you’re working on something good / But if it’s really good / You’re gonna need a bigger room.’ It’s so smart.

Paul: It’s a great metaphor for the artist’s dilemma.

Kahlil: In Sky Ladder, people comment on how things have changed for Cai, and I found it really moving. At one point, the government asked him to alter his design because it doesn’t express the ideas they want, and he acquiesces. But his decision seemed less about compromise than it was about not being reactionary. I think a lot about that. On the other side, you have someone like Ai Weiwei, who never cooperates with authorities. However, his work can sometimes feel like part of a theatre of political rascals. It’s not a judgement thing where I’m coming from. It’s just interesting to see two thoughtful Chinese artists of the same generation and their reactions.

Paul: I think a lot about the relationship between art and politics, or art and activism. Your work has a lot to do with expanding ideas of black representation and identity, which has a political dimension. For me, your work is defined by operating on multiple levels at the same time. It’s romantic, gritty, beautiful, painful, nostalgic, and futuristic all at once.

Kahlil: The art world definitely feeds off political unrest, probably more so now than in the past. It’s like a fashion thing: work isn’t considered serious if it’s not political. I’m black, so I walk out of the house and I’m a news story. I think about an artist like John Coltrane, who was so uninterested in being politicized on any level. This hasn’t diminished how people feel about him as an individual and as a creative genius. John Coltrane and his wife Alice were only interested in a more spiritual longevity and dimensionality. It makes more sense if you weigh political and spiritual concerns. Political ones are far less important than spiritual ones.

Paul: Alice Coltrane is especially interesting because after John’s death, she began to develop this cosmic visionary jazz. She eventually withdrew from public life and opened an ashram and became a spiritual leader. Her devotional music is now being rereleased.

Kahlil: Back when I was nineteen or twenty, I had the chance to film her when I was interning at a photography studio. They were shooting Alice for Jazz Times and they wanted some behind-the-scenes moments. The photographer knew I had a Bolex 16-mm camera, so I found myself filming Alice Coltrane for hours on end when she was in the studio. She’s one of the only artists I’ve met who has a real aura. She walks into a room and it’s like there’s an orange light around her. It seemed like she was floating. It was bizarre and magical. It had a profound impact on my life. She represented this idea of longevity and integrity. She was famous but she wasn’t famous. She was current but she was also trying to be eternal. Years later, I became friends with Flying Lotus, who happens to be her nephew. When she passed away in 2007, I gave him the footage.

…The first time I saw her live I was transfixed…

Paul: That’s an incredible coincidence. And you wind up making the acclaimed short film Until the Quiet Comes for Flying Lotus. The themes and textures of Flying Lotus’s music seem to channel both Afrofuturism and Eastern spirituality. I noticed that one of the pieces in the Bonnefantenmuseum exhibition is called Alice and I wondered if it’s about her.

Kahlil: It’s not about Alice Coltrane, but the connection isn’t lost on me. It’s actually about a contemporary vocalist named Alice Smith. The first time I saw her live I was transfixed. And I’ve been kind of obsessed with capturing that thing I experienced for years now. I don’t know if the piece you’re referring to will be in the show because I’ve made a new piece with Alice that might replace it. She has this really deep soul thing. Like Alice Coltrane, Alice Smith is an artist who isn’t interested in the marketplace. There are very few people as talented and sexy or who possess a voice as powerful as hers. It’s evident even if you just watch a YouTube clip of her performing. Do you know Arthur Jafa’s work?

Paul: Yes, I’m a fan! I was going to bring him up since you edited his documentary Dreams Are Colder Than Death. Arthur’s trajectory is fascinating. He was the cinematographer on Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust and Spike Lee’s Crooklyn, and had become a multi-disciplinary artist, though he’s also making music videos for Solange. I met him at an event several years ago where he spoke about relationships between black music and black cinema.

Kahlil: Arthur has a show at the Serpentine Gallery in London. One of his pieces features a YouTube clip of Alice Smith singing live. I learned about it after I had made this new piece with her. I happened to be talking to Arthur and she came up. It’s so crazy. We’re both obsessed with her!

Scene from the allegorical short film/music video for Shabazz Palaces Belhaven Meridian

Paul: Let’s talk about Shabazz Palaces, one of my favourite music groups. Belhaven Meridian and Black Up are radical and wondrous cinematic gems. Formally, they couldn’t be more different. Belhaven Meridian is about fluidity, whereas Black Up is about fragmentation. I like the way Belhaven Meridian flips the music video genre on its head. The music weaves in and out, and at one point even stops altogether. The camera seems to be observing a number of stories unfolding simul-taneously but doesn’t make us focus on one in particular.

Kahlil: Working on Shabazz Palaces was like the Holy Grail. Those films hold a special place for me, even today. It’s about being inside the music versus being on top of it. I started making this stuff in a post-music-video age, so for me the golden age of music video has passed. Today, there are no budgets and no proper platforms to experience the work. Can you imagine art without museums or galleries to show it? Where do you even begin to look? When I started out, I wasn’t working with much money and making the videos wasn’t a source of income for me either. Belhaven was informed by so many different things. To do a one-take film means you have to know what you’re doing well before you get there. In this case, the camera wasn’t operated by a person. It was attached to a Russian Arm mounted on a truck. The movement is pre-set and you just hope that the orchestration and choreography in the shot lands!

Paul: At one point in the film, the camera swerves to take in a film crew shooting a movie outside a house. The text ‘Sheep Killer c. 1977’ appears above the scene. It’s a reference to Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep, a film that heralded a new black independent cinema in America. You’re an independent filmmaker; however, your films are rarely thought of in that context.

Kahlil: There are filmmakers making great stuff today but it’s becoming a highly specialized space. What used to be interesting about indie cinema has changed. I don’t want to say it has lost its soul, but something’s gone. It’s funny because the technology today has made it so much easier to make films. As I tell young filmmakers, there’s a lot to learn about making compelling moving images. You really need to be a student on a super-real level. Everyone loves movies for sure, but you really need to love Polish cinema from the sixties and Korean cinema from the early 2000s. You have to know about it and have an appreciation for it. Do you know my brother Noah Davis?

Paul: I know he’s an artist and that you both founded an alternative exhibition space in Los Angeles called The Underground Museum.

Kahlil: Noah will eventually be remembered for his paintings, but he had a deep appreciation for conceptual art, sculpture, video, and performance. He was an artist’s artist. He loved the basic soul of what makes great art, no matter what form it takes or who made it or what country it’s from. I have the same approach to cinema. About ten years ago, I was living in Texas working on films, editing stuff for other people. There was one other editor I was working with who really loved cinema. We’d talk for hours about movies. We were completely confounded and intrigued by Godard. There was no characterization in the films, and sometimes no real scenes. I remember thinking, ‘Is Godard that far ahead of everybody else?’ When there’s a real, palpable love for cinema, you tend to have a wide appreciation. Someone I worked for once started talking shit about Michael Bay. I immediately started breaking down The Rock and how he can tell a story so fast given all the exposition. I’ve learned a lot from that guy.

At the Los Angeles’s Underground Museum, Kenzo’s creative directors Carol Lim and Humberto Leon celebrated the premiere of a new Kenzo campaign film, the Kahlil Joseph-directed Music is My Mistress, showcasing Kenzo’s kaleidoscopic spring/summer 17 collections. The short film is the fourth in a series of campaign movies commissioned by Kenzo, and stars actor and activist Jesse Williams, emerging musical talent Kelsey Lu, musician Ish, and Golden Globe winning actress Tracee Ellis Ross. Eschewing linear narrative in favour of divergent glimpses into a bigger story, the picture is an amalgamation of rhythms, visions, and moods, driven always by music. Courtesy Jane Helpern Vice

Paul: I’m fascinated with the question of what makes art contemporary. Godard and Michael Bay are two filmmakers who are almost never discussed in the same conversation. They’re both channelling something hyper-contemporary, albeit in radically different ways – one with an iPhone and the other with an arsenal of money and technology. In both cases, the result is a fragmentation and abstraction of narrative, which might be what you’re getting at.

Kahlil: I don’t know what’s going on now in independent film. I think it’s exciting because it seems like it has lost its path. It’ll find its way, I know. If you look at the history of cinema, what we’re experiencing happens every fifteen or thirty years. Attendance is at an all-time low; exhibitors and studios freak out; the movies look like cardboard cut-outs. I’m excited about the next wave, whatever it’s going to be. The only thing that’s ever moved art forward is a technological advance, like the shift from cutting film to nonlinear digital editing. That’s why I think Godard gets it. His movies actually make money today because they don’t cost anything to make. He’s way, way out there. He’s almost like the scout you send to the frontier to report back on what the fuck is out there.

Paul: I think a lot about Film Socialisme and Goodbye to Language because they’re twenty-first-century films made by a twentieth-century filmmaker. They have a strange blend of radicalism and nostalgia. You and I are basically the same age, and so we have the experience of having been adults before the advent of social media. I’m wondering how you navigate this cultural shift and whether you ever feel the need to unplug.

Kahlil: I went to a conference recently on the science fiction writer Octavia Butler. As quiet and internal and humble as she was, you learn very quickly that she was voraciously reading everything. She constantly clipped newspapers and made notes, and was an ardent student of society. You learn that her insights into the future emerged from a careful study of the present. It wasn’t coming from a place of anxiety or self-righteousness or having an agenda. She was a writer and she was doing research. She wasn’t distracted in her efforts to understand human activity. For a monk or for people who meditate, maybe it makes sense to unplug from all the noise. When they hit Nirvana, that might be when they want to watch Game of Thrones.

Paul: I wanted to return briefly to the subject of spirituality. Much of your work, from the videos for Shabazz Palaces and Flying Lotus to your most recent film Process for Sampha, builds to these moments of transcendence, for lack of a better word, where the combination of music and imagery seem to take flight.

Kahlil: Spirituality is everything. It’s ultimately more important than anything else. We’re clearly spiritual beings because we can’t locate where life exists in someone’s body. Science hasn’t caught up to the moment yet but the evidence is overwhelming. It’s something that’s always operating. For each person, it’s a different thing. It’s mixed with this idea of consciousness, which is related but also different altogether. Everything has consciousness – trees, land, water, cities, individuals – and they all have different agendas. It’s like all these different conversations are happening. I remember this exercise we did in class where we read a Hemingway story and had to think about the words on the page and the way we interpret them as being totally different. It’s a good exercise. People may be saying one thing but talking about something else.

Paul: I know you’re not always keen to talk about your own work. My feeling is that an artist’s responsibility is only to make great art. Everything else is extra. At the same time, I’m curious to know about your process and how you select projects.

Kahlil: When it comes to my own work, I feel like silence is louder. I often think the person in the room who hasn’t said anything all night is more intriguing.

I don’t really know how to answer your question because for me, it’s beyond logic or conscious decision-making. I get different cues all the time, whether I’m out shooting something or in the editing room. It’s really about getting so deep into something that you’re really in it. If I’m paying attention to my soul, it will tell me what projects to do or not to do.

I wanted to get that dub where you’re feeling it in your entire body…

Paul: Let’s talk about one project in particular, Wizard of the Upper Amazon. It’s a two-channel video installation that premiered last year and will be shown at Bonnefantenmuseum. We see a group of Rastafarians hanging out backstage and smoking weed. The black-and-white images and soundscape create a space that’s both sensual and menacing. I watched it via an online link without knowing any backstory or context. What can you tell me about it?

Kahlil: Oh wow, that’s crazy. The piece has an important performance element, which totally transforms the experience. When it’s installed, you walk into a pitch-black gallery. The only light is from the huge projections. The gallery is set up to resemble the film. In fact, we filmed in the gallery and the Rastas you see onscreen are actually present in the gallery smoking weed as part of the installation. The viewer walks in and tries to watch the film but can’t help but get a contact high. We had huge subwoofers as I wanted to get that dub where you’re feeling it in your entire body.

Paul: Sounds intense! Where does the title come from?

Kahlil: Henry Taylor is a fantastic painter who was friends with my brother, which is how I met him. We were in Greece and he was telling me about an upcoming show. He wanted to run some ideas by me because he wanted to mix it up and not just show canvases. I was in awe that he was even soliciting my opinion on this! Henry’s an amazing storyteller, and I said to him, ‘The craziest thing you ever told me is when you met Bob Marley in 1979.’ Bob was playing in Santa Barbara and somehow Henry, who was nineteen at the time, drifted backstage and found this room full of Rastas. Bob was there, eyes closed, sitting against the wall. All around him are these Trenchtown Rastas, but there’s one empty chair next to Bob, so Henry just sits down.

Remember, this is 1979 and Santa Barbara is really white. It’s like this alien ship of blackness has landed there. As you know, weed was insanely illegal back then. But because it’s Bob Marley, the local authorities permit him to smoke in this back room, instead of onstage. They literally bend the law in order for Bob and his friends to smoke in peace. This is what I call high-level black space. It’s controlled on every level. All the Rastas wonder who this kid is that dares to sit next to Bob. After about twenty minutes, Bob opens his eyes and starts talking to him. This is Henry’s idol, so he doesn’t know what to do. But Bob’s the nicest human being, and so Henry just starts talking about a book he just read called Wizard of the Upper Amazon.

Six weeks later, I’m back in Los Angeles and Henry calls me. He can’t stop thinking about the idea and he asks me to stage it. I was honoured. I decided to make a film installation and was fortunate to work with Blum & Poe. It was my first time collaborating with an art gallery and they were really supportive. We reached out to Damien Marley to use some of his music on the soundtrack. I’d been interested in taking sound to another level and I worked a lot on the soundscape and then created this intense sound matrix in the gallery.

At the opening, there was a line around the block. I stayed in the gallery the whole night, it was so dark, my friends never recognized me. As a filmmaker, you never get to experience a piece with the audience like that. It was amazing.

Paul: You transformed the gallery’s literal and figurative white space into a literal and figurative black space. I’m curious about the legal implications, since only medical marijuana is legal in California.

Kahlil: The gallery consulted its lawyer at length, and since the opening was only a couple of hours, getting arrested seemed highly unlikely. In the end, the show went off without any problems. But of all the museums I’ve been approached by to do a show, it’s funny that I’ll be restaging Wizard in the one country where weed is legal nationally! Museums tend to be tricky because they aren’t private spaces like galleries. I am really impressed by the Bonnefantenmuseum because they’re willing to do it and they’re open to the general public.

Paul: Wizard also seems to be about creating an alternative social space, a kind of collective dream. But it’s also about engaging an audience in a different way through performance. Now that your work is gaining more attention, I’m wondering how this recognition shifts your focus or perspective.

Kahlil: I can’t imagine that Chris Marker would have ever imagined that some black kid born in Seattle in the eighties would be studying his work on a micro level like I did. I have to imagine that there’s a kid in the future from some far-off place that I’ve never visited who will understand my work more than the people who live down the street from me do now. That’s crazy and exciting to me. It’s the beauty of humanity, in a way. There are really magical moments all the time, and you have to remember that. Both my dad and my brother died way too young. My dad was fifty-two and my brother was thirty-two. If they ever spent a moment of their life anxious about anything, it didn’t matter. It’s hard to explain this stuff. It’s like sending postcards from the future.