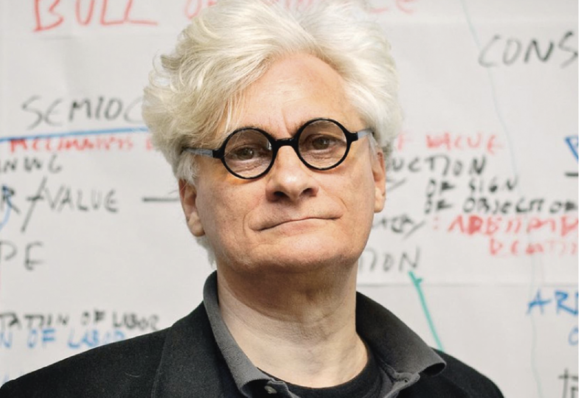

In his revolutionary and intellectual en-deavour, Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi has always put desire and pleasure at the forefront of his resistance to capitalism. A founder of the famous ‘Radio Alice’ in Bologna and an important figure of the Italian Autonomia movement, today he is a prolific writer and media theorist and activist. In this age of impotence, Bifo calls for the upheaval of the social and erotic body of the general intellect, celebrating the excess of poetry and the ambiguity of conjunction. Amidst this global depression, according to him, meaning can be found only in the shared pathway of sensuous consciousness to the ‘oases of friendship, love, intellectual and erotic sharing, conspiration and projection of a common landscape.’

Reading Bifo’s The Uprising, in which poetry is the excess of language, I had to think of flirting as the excess that precedes conjunction. Flirting pushes the gamble, leaving space for the ambiguity of communication wide open, implying trust and loss of control. Both poetry and flirting are strategies of reactivation that resist quantification and capitalisation. When flirting with no expectations, we enjoy our time and build a space for imagination free of competitive acquisition and accumulation. As an economy of gift and expenditure, flirting reactivates the heartbeat and breathing. Flirting makes us anti-nostalgic – as yearning is invested in the now, recounting our past becomes a valuable shared experience of reciprocal knowledge.

From his (collective) experiences in Bologna, this conversation lingers on the excess of eros that spilled from the folds of his practice and thought, as an occasion to talk about desire and friendship, pleasure and subversion, senescence and care.

Giulia Crispiani: Pleasure or desire?

Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi: You know, I never thought about the difference between pleasure and desire. It is something that does not belong to my philosophical approach because, actually, I started thinking about desire after meeting Félix Guattari between 1976 and 1977 and of course, the focus of Guattari and Gilles Deleuze is almost only on desire. The word pleasure does not belong to their conceptual framework, and I probably never made a distinction between these two concepts, because I did not perceive that difference in my personal life. Now something has changed in me, first of all in my erotic body, and in my physical nervous organism. All of a sudden, I’ve started understanding the conceptual distinction. Why so? Because, senescence, getting old, growing old, is essentially about this dissociation of desire and pleasure. Growing old means a growing inability to feel pleasure, to attain pleasure. I say attain, because it is very much a problem of finality. Pleasure is at the end of desire if you want and at the same time is at the beginning of a new desire. One could say that desire is tension and pleasure is the relaxation of that tension, but at the same time pleasure is a sort of mental and physical recharge. This becomes problematic when your body becomes unable to feel pleasure. This is new for me and a little bit embarrassing in life, but also in the philosophical field, because all of a sudden, I am obliged to ask myself: if desire is tension, what is pleasure in itself? Anyway, this is one of the philosophical conceptual subjects that are changing for me in the process of senescence.

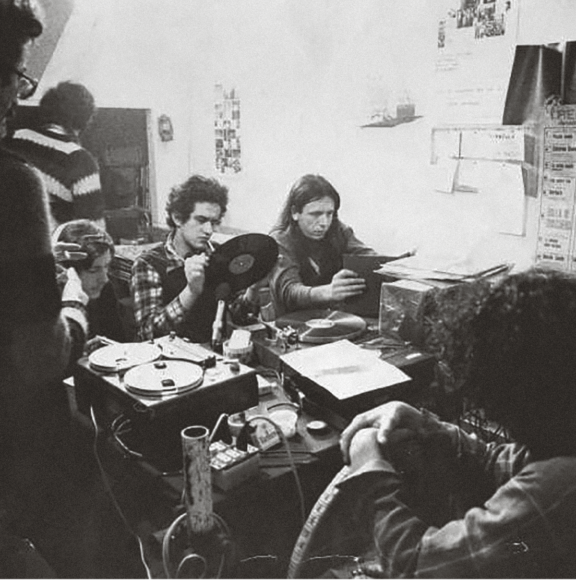

Radio Alice was an Italian Pirate radio broadcasting platform from Bologna. It started transmitting on 9 February 1976 using an ex-military transmitter on a frequency of 100.6 MHz. The station was closed by the carabinieri on 12 March 1977. Radio Alice then re-opened for two years and became politically aligned with the autonomism movement. Radio Alice’s output covered a myriad of subjects: labour protests, poetry, yoga lessons, political analysis, love declarations, cooking recipes, Jefferson Airplane, Aria or Beethoven. Participants in the station included Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi, Maurizio Torrealta, Filippo Scòzzari and Paolo Ricci. Courtesy: Jose Luis Espejo Díaz

Giulia: Considering resistance, sub-version and the struggle, could we agree that your life was dedicated to pleasure – or rather desire? There’s a certain pleasure in the struggle.

Franco: Let’s say that in my mind I have always been persuaded that the erotic field belonged to desire. Now, I understand that my life has not been so bad, because I have never been able to distinguish desire and pleasure, as they have been very close experiences throughout my life. Existentially speaking, I have been very much interested in pleasure. Absolutely yes, but in my conceptual framework I never distinguished them and I thought that pleasure belonged to the sphere of desire. Only now I understand that it’s not the same, both conceptually and erotically speaking.

Giulia: Speaking of dedication, what was the dedication throughout your practice, your drive?

Franco: I am not so able to distinguish between social excitement – call it rebellion, revolution, movement – and erotic excitement. In my personal experience, these two fields have always been very much entangled; they implicate each other.

The political relation with people was charged with the pleasure of meeting bodies, of exchanging words, of discovering places and questions and so on. At the same time the erotic relationships that I have experienced were very much charged with some sort of political euphoria. If you brutally ask me: yes, but you have to decide between eroticism and the movement? Well, probably I’d say now I would prefer to be an erotic person but in other moments of my life I had decided to be a political person, but this choice is stupid, you don’t have to choose.

Giulia: What is the relationship between the pleasure of subversion and the desire to subvert the norm if the norm is unjust?

Franco: This is the problem of the relation between the ethical sphere and the erotic sphere. I try to ask myself, what is the meaning of the word ethics? What is ethical? And I’ve found many answers in the history of philosophy. Generally the answer to the question, ‘what is ethics?’ is the choice between norm and transgression. Anyway, the problem of normativity is very crucial in the philosophical definition of ethics; this is why ethics has always been a failure. Ethical behaviour is a sort of idealistic assumption that never complies with real life. Why is that so? I think that if we want to understand ethics in an effective way, we have to link ethics and erotics. I mean, if you think that you must do something because it is written into law, or in the mind of god, or in the ethical abstraction, if you think that ethics is different and also contradictory to or in conflict with erotics, you are transforming ethics into something absolutely weak, impotent. The problem is that an effective idea of ethics can be funded and built only if you are able to identify or approach or put together pleasure and duty. I do not believe in an ethical society in which every person is doing what they are obliged to. I strongly believe in the possibility of an ethical society in which everybody does what is their pleasure, because pleasure identifies with the good. The monotheistic culture has dissociated erotics, eros and agape, the erotic good and ethical behaviour, duty. This is the fundamental misunderstanding that has made ethical behaviour impossible or absolutely exceptional. In fact, I would say that communism can be effectively conceived only if we are able to make the relation with others a relation of pleasure. The concept of compassion, or empathy, or sympathy, is putting to-gether the pleasure of being with the other and the necessity for solidarity. Solidarity is not an ethical duty but a pleasure when the relation between bodies enables it. Obviously, this may sound idealistic, as we think that pleasure is identified with the selfish accumulation of something. We are unable to think dissipation as pleasure…

Futurability: The Age of Impotence and the Horizon of Possibility is Bifo’s attempt to find in the middle of despair the signs of a possible joy, of possible ways to reverse the privatization of happiness. Though as the title suggests, the book strives to imagine a way out from the current impasse, the space for a mutinous alternative is not to be found in some faraway future, but right here and now. Courtesy: Giovanni Vimercati

Giulia: …excess, expenditure…

Franco: …yes! this is why I think that an erotic conception of the relation with the other would be the best introduction to an ethical politics.

Giulia: Let’s go back in time, beginning with Radio Alice and the experience of Bologna in the 1970s, in the pleasure of being together or this ‘small group in multiplication’ and the consequent pleasure of doing. Scandal as a technique with which to catch attention and the label ‘obscene’ that Radio Alice was given by mainstream media. Desire was at the forefront of the movement. Let’s talk about the erotics of subversion.

Franco: Let’s try to reconstruct the historical framework of the Bologna experience, from 1976–77. The movement, or that kind of social process or social existence that we called the movement, was essentially taken between two poles that you can identify historically and geographically: one pole is the Mitteleuropa experience of Marxism, of political thought and critical theory. The other is the Californian assertion of pleasure: the pleasure of the mind, drugs, erotic excess and so on. Obviously, I say California because in those years we identified this pole with the Californian rock culture and the psychedelic experience. Anyway, Radio Alice was the product of a meeting between some young ‘Californian’ people and some serious Marxists. I was among the Marxists. This clash, and meeting of the two different cultures, created a sort of new possibility. The idea was that in the revolutionary process, in the history of the movement, what is really at stake is not the political form of the state or the economic organisation of society – although of course that’s really important but it’s not the main point – but desire, and pleasure, I want to add today. But let’s better understand what desire is. Desire is not to be understood as a lack, a loss, the effect of not having something. On the contrary desire is the projection, the imagination of a possible condition. Desiring a person, desiring a thing, desiring an event does not mean craving that object. Desire means to imagine yourself with – I would almost say mingling with that event, that situation, that person. Falling in love does not mean to crave or to be in need of that body or of that person. It means to imagine me and you together, to imagine a situation in which that body, that person, that thing, that event changes itself. If I desire you, it’s not you that I desire. What I desire is me with you, where we are the same thing, the same event. In the 70s, precisely after 1974 we started reading Deleuze and Guattari and this was a sort of precipitation of many intuitions we had in mind. The effect of our reading was understanding that the movement is essentially based on the ability of being transformed into a political process, something that belongs to the collective, to the common drive and desire. The battle of desire is at the core of the political battle. That does not imply that problems such as salary and political rights and so on become irrelevant – not at all, on the contrary. The problem is that in the process of deploying this desire you have both the necessity and the potency. Desire is the field on which political potency is built, if there’s no desire, no politics can take place.

Giulia: I am always jealous when I see videos and read about Bologna in those years. I always get this feeling of envy, as if I’d like to be there to witness it with my own body. It’s a sensible jealousy of flesh: the turmoil, the physical presence and the proximity of bodies, indeed. What does your body remember of those years, sensibly?

Franco: Frankly speaking, if I think about my erotic experience, I do not focus on 1977. Not at all. It was those two-three years let’s say 1976–79 I remember as years of intellectual excite-ment, of pleasure of being together, but the energy was so invested in this social dimension of eroticism that my personal life… if I can be brutal, I’d say I did not make love so many times. Why is that so? Probably because my eroticism was taken much more…

Giulia: …by the collective body…

Franco: …more by the collective excitement than by the focalisation on the sexual. Although the effect of that kind of intellectual and erotic discovery lasted many years. I would say in my personal life, the erotic years come after or before. 1977 was a year of energetic dissipation and intellectual accumulation. All of a sudden (I speak of my personal experience but maybe I can speak for my friends as well) during that one or two years, we discovered so many things that the rest of our lives became dedicated to the deployment of that, intellectually but also erotically speaking. Our eroticism has been sort of fed by that kind of discovery: the strong relation between pleasure and the crowd, and pleasure of a crowd, which becomes a movement. This process is, erotically speaking, enormous. You see it now in Chile. I saw this young girl carrying a sign saying, ‘it was not depression it was capitalism’ – that is the meaning of the movement. The movement is the ability to overcome depression thanks to a meaningful and erotical relation with the body of the others. This is what we discovered in those years.

Giulia: You wrote pornographic novels at the beginning of your career, was that before or after?

Franco: Before. In October 1970, I took part in a demonstration that ended in a fight against the police. I took part in it partially unconsciously. I did not know that my comrades had decided to fight the day before, so I went barefaced. The police recognised me and my face was in the newspaper the day after. I was wanted by the police and I was twenty years old. I had to escape but I had no money. A friend of mine asked me then if I wanted to work for his father, who was the director of one of the most important pornographic publishing houses in these years: ABC, the first who published naked women in Italy. So, I went and started writing porn books, and I have never been as rich as in that time. I was earning way more than my father, who was a school teacher. I wrote seven books in a year and a half. Then I was captured by the police and stayed in jail for a while, and my career as a porn writer reached an end. This happened between 1970 and 1972, after 1973, porn books kind of disappeared as videocassettes began to hit the market, and all of us writers became unemployed.

…and obviously you know that language often leads to sex, but sex leads to language, and this continuous game of sex and language is the essential meaning of eroticism…

Giulia: You said before that the relationship between pleasure and desire changed through time. If poetry is an excess of language, then, in its ambiguity, is flirting an excess of touch?

Franco: Flirting? Flirting is beautiful. I would almost say that touch is an excess of flirting, let me think. Oh no, you’re right! You say flirting, I propose another word, which is courtship, corteggiamento. In my perception the highest form of human relation is courtship. Italian, Spanish and Arab literature begins with the problem of courtship, the troubadour, the Dolce Stil Novo, all this is the beginning of modern literature and what is it? It is an attempt to transform nature into culture – craving with desire, the transformation of a physical drive into words, into language and obviously you know that language often leads to sex, but sex leads to language, and this continuous game of sex and language is the essential meaning of eroticism. You can’t understand eroticism if you don’t understand what words mean to desire, as desire without words is brutality. This is very important. I think one of the main problems of the present generation is the difficulty of linguistically elaborating desire, but also sentiments and feelings. The point is linguistic elaboration. So is linguistic elaboration an excess? Yes, in a sense – I am leaning so much towards your body that I speak, and it’s incredible, words come out of the flesh. Obviously, I know that words are a way to come together in flesh, but in this double relation one is the excess of the other somehow. Eroticism is all about these mutual implications.

I would say that for once I don’t stop courting. I still think that a rich relation between people is rich only when you’re able to imply desire in your words

Giulia: What is the relation now between flirting and senescence, flirting and impotence?

Franco: It’s difficult to answer this question because I don’t know enough yet, the discovery is underway. I would say that for once I don’t stop courting. I still think that a rich relation between people is rich only when you’re able to imply desire in your words, and you cannot imply desire if you don’t feel desire of course. So, sincerity is certain, because of course you can pretend, but why would you? In my experience (and I think in the experience of men and women as far as I can say), the words of courtship, le parole cortesi, have always been ambiguous. You could also refer openly to sex, but courtship has to be a gratuitous activity… Of course your final goal is to end up in bed with that person, but you never do it only because of that; this is not a necessary part in the activity of courtship. So, senility is probably producing an effect – I say it but at the same time I am a little bit ashamed of it, I never thought about it before. I am probably talking ‘courtly’ more than ever before, because the gratuitousness of my activity is so clear, to me and to the other. It’s some sort of artistic activity and I like it in itself. I would be insincere if I’d say that I like courtship without sex. I like sex very much, and I resent the growing difficulty I experience with it. A word comes to my mind, ‘sublimation’: we know that art, poetry, words and so on can act as sublimation, but generally sublimation in the Freudian field is intended as a replacement of something that you cannot have – ‘I cannot make love so I write poetry.’ No, in my experience I’d say that I write poetry because I like sex and vice versa. Maybe the process of getting old is making the sexual conclusion more and more difficult or impossible, but that doesn’t mean courtship becomes something empty. It is never empty for me, I feel the emotion of courtship, even if I know that I cannot have sex.

Giulia: Is impotence a predominantly manly topic? And is that so no pleasure can be had unless it is men who receive pleasure?

Franco: That’s a difficult question for me, for a very simple reason, I cannot speak of a sexuality I don’t have experience of. As far as I know, impotence, sexually speaking, does not regard only men. It’s a male obsession, but not a male subject. I mean the inability to have pleasure, sexual pleasure, is not peculiar to men, when it comes to senility but also generally. The problem is that patriarchal society has built male identification on sexual potency, while female identification is not absolutely based on that, also on generation and procreation (this is another very interesting question, but a whole different subject). For men, impotence is an unspeakable subject. It’s something that cannot be dealt with because it questions the very social, sexual, cultural identity of men. It seems not a problem for women who are much more detached in their lives from their absence, refusal, impotence in the sexual field. I’d say that women have an erotic expressivity that is generally speaking much larger than the masculine sexual counterpart. Eroticism is identified with sexuality for a man, but it’s much wider for a woman. I am speaking in a very general way, because I know very well that you can have women who live sexuality in a very masculine way and the other way around, males who live eroticism in a non-obsessive sexual way. Still, culturally speaking, you can identify masculine and feminine experience as a different sexualisation of eroticism.

If you really want to invest your time, you need to invest your pleasure and your desire in that kind of activity. You have to find your eroticism in that field.

Giulia: I really liked this concept of conspiration, as if we agree that flirting is an excess then it can, as poetry does, reactivate breathing. How do we conspire for the intellectual sharing to become erotic again?

Franco: You know, if I look at the present situation, particularly the cultural and psychological condition of the connective generation, of the generation of people who have learned more words from a machine than from the voice of their mother (my definition of the connective generation from a psychological point of view), it’s difficult to imagine what erotical conspiration means. I mean difficult… It’s a problem, probably the main problem. I don’t know if people are making more or less sex than in the past, according to some survey it seems so. Intuitively I’d say it’s easy to understand that if you spend eight hours or more in front of a screen you won’t have much time to make love. David Spiegelhalter wrote a book titled Sex by Numbers (2015), about the transformation of sexuality in the past thirty years. Spiegelhalter says it’s very difficult to get precise figures around sexuality because people don’t answer honestly, but according to his surveys, in the 1990s people were making love on average five times per month, in the first decade three times per month, and now two times per month. Anyway, we’re not interested in the frequency but in the quality of that experience. If you think about the amount of energy that a precarious cognitive worker today is obliged to invest in the productive activity of connective interaction, you understand that this absorbs precisely that kind of energy. I mean, we know that a metal worker in the 19th century was putting loads of physical energy into their work, and I think they were not very happy either at a sexual level but their investment of energy was essentially muscular. Nowadays, the cognitive and precarious worker is obliged to invest their mental, nervous and desiring energies in their work and social exchange. That explains why social desire is somehow disappearing from the social field. How can we counteract such a tendency? That is the core of the political problem of our time. Taking part in a social process is not only a matter of social persuasion. You don’t take part in demonstrations and occupations only because you are persuaded that it is politically and morally right. If you really want to invest your time, you need to invest your pleasure and your desire in that kind of activity. You have to find your eroticism in that field. This is the essential difference between the movement and institutional politics; institutional politics is for money or for some sort of ideological persuasion. If you want to conceive a social movement able to absorb social energies, you have to think first of the desiring energies. The present precarious cognitive worker is deprived of this energy. Going back to Chile, I understand that the social mobilisation that is happening these days in many parts of the world is the only way to reactivate eroticism. Not because politics is erotics, but because these bodies being together in a place are withdrawing from the connective abstract exchange. This kind of remobilisation of the body makes possible a reactivation of desire.

Giulia: What is your idea of the alliance between desire and friendship?

Franco: I am not so able to distinguish between the two. If I think about my love stories, they have been sometimes very crazy, but at the end stories of friendship. It’s first of all about friendship, about the pleasure of seeing each other and saying silly things, of sharing a very special field of mutual understanding; this is friendship. If I think about my relation with men (I don’t have but one gay experience, that is sort of forgotten in my mind, it’s not part of my living experience), so if I think about my relation with male friends, obviously I perceive a difference, but it’s not really totally out. The male level, layer, dimension, whatsoever of seduction, implication, coinvolgimento and pleasure is essentially the brilliance, the euphoria of sharing words and mental discoveries. In a certain sense I’d say that the real goal of an ethical, erotical philosophy is to transform all life into an erotic experience. Of course, sometimes it’s impossible, you suffer from headaches, you are in a crowded train, fascists are everywhere, it’s not always possible but this should be the goal of eroticism: not to exceptionalise sex, love and so on, but rather to spread eroticism everywhere. Communism is for me a condition in which every social relation is based on pleasure, on discovery, on secret, on enigma, on creating labyrinths of understanding, and also touching the body of others.

Courtesy: Dutch Art Institute

Giulia: Sensuality and laziness as conditions for socialisation?

Franco: Absolutely yes, you are continuing what I was saying before. In the capitalist sphere socialisation is exactly the contrary. Socialisation means to transform life into value, capital and accumulation – dis-eroticising the expression of life. But my opposition to capitalism is essentially based on this. I mean, capitalism is that sphere in which human beings are obliged to renounce the possibility of pleasure and transform it into economic value; the process of a happy socialisation is based on laziness in a good sense, laziness as a non-alienated activity, an activity not based on investment. Sensuality is the openness of your sensorium, your eyes, your ears and so on, to the possibility of sharing pleasure with the body of the other. And I go back to the problem of getting old: senescence is essentially a reduction, a downsizing of the definition of perception. You see why senility is so important for the definition of eroticism in a negative sense. I confess, but it’s my ability to see, to smell, to touch that has lost precision, I can touch but my fingertips have lost a large part of their definition, of their precision. It’s the relation between my neurons and my fingertips and my eyes. Sensuousness is the faculty of perfecting, elevating, exaggerating the relation between sensorium and cerebral activity, and brain.

Giulia: If knowledge fulfils itself through the body, what did you learn from all your experiences of this erotics of subversion, speaking from your own body?

Franco: The problem is that I did not learn anything. In the field of eroticism what is the meaning of learning? You have an experience. Of course you learn something about the body of your partner, but only up to a certain point. In fact, you have learned nothing. This absolute singularity of every body and the absolute singularity of every different linguistic communication is interactive activity. Every person you meet is totally different. Obviously you learn many things, but you don’t learn the most important thing, singularity. You are always at the beginning. This is why every time you start a close relationship of sex, courtship, friendship, you feel a sort of emotion similar to the emotion you had the first time. Probably even more. If I think about the emotion that I felt when I was seventeen and the emotion that I feel today, obviously I know much more. But I don’t know the essential thing: what happens now? Eroticism is also about the singularity of each event in your life. If you don’t understand this, you understand nothing about eroticism. The serial seducer is someone that has nothing to do with eroticism. He’s someone who knows very well how to seduce, how to have sex and so on. But he does not know what eroticism means, as eroticism is the absolute beginning of the experience. Many things are similar but the essential is not.

Giulia: What about obsession?

Franco: Obsession is a sort of loop, a recursive ritournel that takes you in a sort of circle imprisoning your brain – a compulsive state of mind, a compulsive idea or image that forbids innovation, and obliges your movement in a circular repetition of steps. Labyrinth is the name of obsession, but this labyrinth might be full of joy. Think of sexual jealousy, the obsessive return of your mind to the unspeakable (ob)scene that imagination is projecting on the screen of your pain, of your pleasure. I like jealousy, the desire of the beloved body possessed and caressed and penetrated by the infinite beauty of Otherness. I like watching you when your lips approach the sex of the glorious sensuousness of the other: the not-me fucking you and fucking me through the sensuousness of your mouth. Obsession is the trap of this pleasure, the inability to come back to reality. Or the infinite return of reality transformed into imagined pleasure as suffering.

…A voyeuristic attitude is for me absolutely good, perceiving sex everywhere, eroticism everywhere…

Giulia: Your latest book is titled The Phenomenology of the End. How do we take pleasure to the end?

Franco: This is what happens at the end. I am the end. Maybe I will live ten years longer, I hope not, but maybe. In a sense we could say everybody is at the end in this moment because of the common share, but no, I speak for myself. More or less I can say that erotically speaking I can enjoy essentially what Freudian people call sublimation. Sublimation is almost everything for me. I cannot deny that there is some bitterness in saying that, I like all those banal things. I don’t despise sex, absolutely not. But at the same time, I think beyond sex, and sex is there, sex is never ending if you’re able to transform sex into eroticism and eroticism into sublimation. But what is the meaning of this word sublimation? Freudian people use the word with some sort of compassion – oh my poor boy, you cannot have sex but you can write poetry or read – like a sort of downgrading of that high pleasure. I think that sublimation is real excitement if you are able to perceive the pleasure of the other. A voyeuristic attitude is for me absolutely good, perceiving sex everywhere, eroticism everywhere.