Many years ago at Tate Britain, I picked up a small paperback written by an artist called Ed Atkins. Stacked in a darkened exhibition space that preceded a screening room, the diminutive publication immediately skewered the Pavlovian inertia usually produced in me by long texts in exhibitions.

Titled Tumor, it was a startling and seductive homily to abject flesh, coagulated blood and oozing life.

The back page reads; ‘This book will change your life: it will conjure a tumour inside you. In your colon, or perhaps your wet brain, or your left kidney, or secreted within your right testicle. Clustering inside your ovaries, your pituitary, your breast. Etc.’1

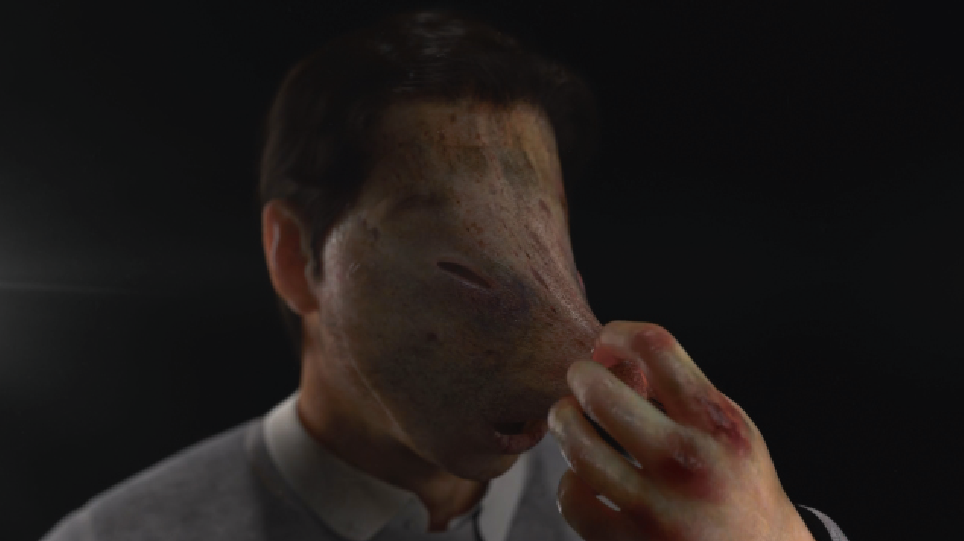

Safe Conduct, 2016, Three channel HD film with 5.1 surround sound, 09:04,21:51 mins Courtesy the artist and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi

This is art whose affect is so insidious, it can alter your biology, make you sick…

The book takes as its cues many of the themes that run through Atkins’ work: a concern with the human body and its leaky mortality. Julia Kristeva’s concept of abjection has been studied and embedded in visual culture and looms large in Ed Atkins’ works, albeit reframed and contemporized through the consideration of digital media and imaging.

In many of Atkins’ films we encounter the same evolving, or perhaps decaying, protagonist. This articulate and empathetic figure is by turns tortured and enlightened. Like any one of us he grapples with the knots of existence. The bathos of his situation is tangible; he is self-consciously imprisoned in his own fictive status.

The digital realm in which this character exists offers a challenge and complexification of conventional modes of intimacy. Can pixelated bodies, projected irrespective of geographical constraints, provide a foil to our desires, or perhaps have their own? How does desiring flesh translate into pixels? Does the digital representation of our lusts and fears satirize or celebrate them? Atkins’ work troubles itself with these questions.

Hovering in space, the nameless protagonist quivers with existential doubt, desire, and hubris. This digital being – riven by anxiety – dwells on mortality and narrates keenly experienced conflicting emotional trajectories, articulated with literary intensity.

Atkins’ avatar, perhaps a confessional version of the artist himself, can be read as a distorted HD reflection of our grotesquery and abjection, an exteriorized version of the artist’s own preoccupations, and a vision of white male subjectivity as part of an entropic and schizophrenic society. One walks away from his installations feeling provoked, seduced, unsettled. Atkins’ subject seems so uncannily alive, individuated and sympathetic, but he is no more than a projection; a presence with no real existence. This simultaneous illusionism and structural foregrounding drives you in as a confidante, whilst drawing back the curtain on the process of digital imaging; the aesthetic of our times whose drive to verisimilitude is paradoxically self-defeating – the more HD we get the less we associate with the hyperreal images that result. The pores and crows’ feet of our favourite stars: that would defeat the core of their desirability.

Natasha Hoare: The relationship you strike between the viewer and the protagonist in your films is a close one. Intimacies are whispered and sung in the dark spaces of the exhibition. What is the potential for intimacy in the digital world? Is it possible for a prosumer to fall in love?

Ed Atkins: Surely. Do you mean exclusively digitally? I don’t see why intimacy or love should necessarily be corporeally contingent.

Natasha: In the Instagram image economy, love and intimacy seem to have become hollowed-out tools for self-aggrandisement and to attract followers. In his novel The Possibility of an Island, Michel Houellebecq speaks of the long, slow decline of Western sexuality along the axis of the disappearance of intimacy. Do you see things through a similar trajectory?

Ed: Houellebecq’s not exactly an authority on contemporary sexuality! I think most people can still tell the difference between social media representation, and whatever happens when they’re with other people IRL. I’m also not sure it’s possible to ‘hollow out’ love and intimacy. I think those ideas are both infinitely plastic and entirely immutable – in sensation and unconscious understanding, if not in representation or faith.

Natasha: I agree Houellebecq is unpalatable, misogynistic, gross – yet there is something in his misanthropy that speaks to our age, the pallid underbelly of liberalism, our own closeted depravities reflected back at us, perhaps?

Ed: The writers that inform my literary style at the moment are for instance Keston Sutherland, Simon Thompson, Lisa Robertson, Leo Bersani, Hubert Fichte, Gillian Rose, Ikkyu.

Any incorporeal representation or surrogate triggers a yearning for the corporeal…

Natasha: Keston Sutherland’s most well-known work Ode to TL61P includes self-proclaimed love songs to a now obsolete product ordering code for a Hotpoint washer-dryer. I can see how his writings speak to you in the way the plotting of eroticism and sexuality against globalized consumer culture and politics is addressed. In terms of the impact of technology, the language used is spliced, almost as hypertext. You of course create a digital image. Traditionally love and sensuality have been matters of the flesh. The very etymology of the word ‘sensual’ insists on physicality. How do we love what is incorporeal?

Ed: I don’t think we do. Any incorporeal representation or surrogate triggers a yearning for the corporeal. Part of the overwhelming queasiness one might feel in the face of an overtly incorporeal thing is founded in an encounter with loss. I’d think. And if it’s not overt then it’s a lie, and therefore not a response to this incorporeal thing.

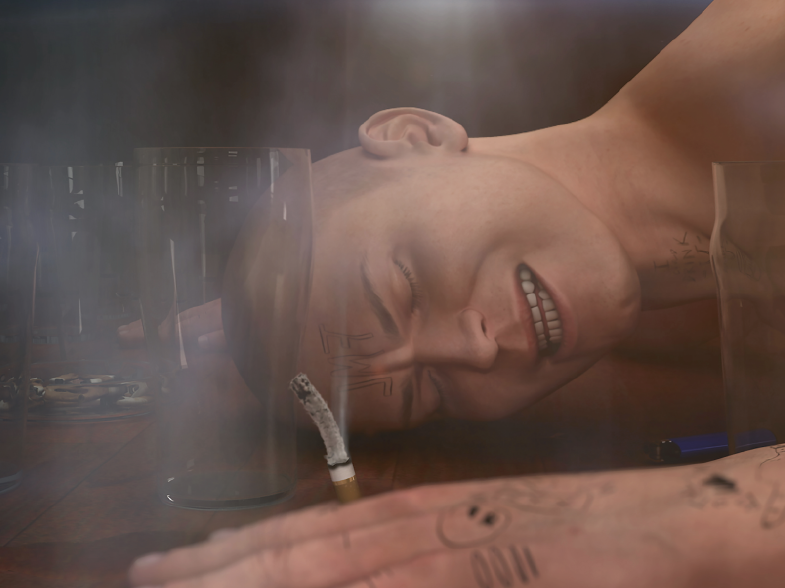

In the work Ribbons, (2014) a computer-generated avatar called Dave talks and drinks and smokes, sings and finally deflates like a perished balloon. Dave is fit, hunky and six-packed in a pub-brawler sort of way. He berates us, offers asides like

Kevin Spacey in House of Cards, talks at us rather than to us. And he’s always got a fag on, either in his mouth or burning down in his worryingly extruded computer-generated hand. Dave looks a bit like Atkins, who has mapped his own features on to the off-the-shelf avatar’s physiognomy. The result is like a moving photo-fit image that never quite gels. You wouldn’t approach this guy on the street. There is something worrying about the mobility of the mouth, those perfect teeth, the eyes that dart about as though through holes in a mask… Courtesy The Guardian

Natasha: That’s beautiful. This state of yearning is very palpable in your films. There’s a Portuguese word that comes to mind; saudade means a specific form of melancholic longing for something or someone absent. Historically the Portuguese were sailors and fishermen, so the word must have developed to express the experience of being left at home when their men went to sea. Contemporary Western culture has a tangible saudade for objects that have authenticity, that are part of a pre-digital past. We have a mass cultural longing for the ‘real’. Is your avatar a cipher for the real, one that signals a state of mourning for a stable sense of selfhood?

Ed: Something like that, though maybe less self – which is maybe constituted by melancholy – loss – in this figuration – and more body.

Natasha: The thin ethical line of resurrecting dead actors continues to be trodden in Hollywood. With digital media death is no longer the final frontier. Is the promise of eternal digitalized life a hallucination that our corpulent frames give lie to?

Ed: Hallucination, probably.

Natasha: Does the idea provide any creative fodder?

Ed: Ha. Yes? I mean, not for me directly but certainly for some rote imaginations that crave familiarity, to call back history. Though I think really the ethical squib that spaffs when Carrie Fisher is digitally reproduced has really to do with how shit it looks! How recognizably NOT Carrie Fisher that thing is. The horror is at its impudence, its ugliness, its poor rendering.

Natasha: Yes, the recreation of Princess Leah for Star Wars is a grotesque image. I’m conscious of creating a dichotomy between nature and technology here. Is this a misleading one? Are the two inextricably interconnected? We seem to be led down many dead ends in reinforcing their opposition.

Ed: Of course, totally wrong, mis-leading, learned horror.

Natasha: In previous interviews you have discussed death a great deal in relationship to your work. Is the art object itself a cadaver?

Ed: No. A cadaver of what? Purpose? A tool? That’d presume, at least figuratively, a life beforehand. Or maybe a meaning. Or a hierarchy or something.

Natasha: Many see the autonomous art object as dead, that the white cube is a graveyard. There is impetus to be making politically engaged art. What line do you wish your work to tread?

Ed: I’m out to make deeply committed, responsible, oblique, thrilling things that really move people.

Natasha: That’s interesting, ‘that move people’ – how do you judge the affective qualities of your work? Is film the greatest medium in this regard, working as it does through sound, image and time?

Ed: I don’t really judge it in any way other than by how it moves me. And, maybe audaciously, presume that if it can do that then maybe it will move someone else. Like, shove them across a room. I like film a lot, so it’s kind of the form I come back to as that which is most moving.

Natasha: You’ve written about abjection before, and quote Julia Kristeva*, but contemporise her theories through a consideration of digital and social media, and the social inequalities embedded in both. Computer animated bodies in art seem to be abject ones, whose pixels degrade and bodies paradoxically age, leak, bleed. What is the tension between abjection and the digital body?

Ed: It’s a grotesque parody, an insult. It’s a particular kind of queasy uncanny that’s not really predicated upon fear but rather a mockery. Maybe also the affectivity of abjection has to travel further, make a greater leap – and so be more gratuitous – in order to achieve its sloughing of intolerable body bits.

Natasha: If we can agree that your protagonist in, say, Ribbons (2014) represents the abject body, can we view abjection as a position of empowerment, one that ruffles the smooth feathers of high capitalism?

Ed: I think so.

Natasha: Kristeva first formulated her definition of abjection at a time in which the HIV crisis loomed large. How do you think it re-amalgamates in the present?

Ed: Digital representation of self means the body is, I think, transported further afield. Not just to a kind of personal suspension of disbelief, but to the clouds and farms of digital no-place. Abjection, working hard, might retrieve bodies and so concomitant material empathies, sensitivities, mournings.

Natasha: Is there then a freedom to be had in digitally representing our bodies, in our ability to flee the traps of time and space? Your digital self-representation appears much more melancholic than this utopic sentiment …

Ed: The figures aren’t me; they’re not my personal avatars. At least, not only. It’s narcissism, probably.

Natasha: Should exhibitions be uncomfortable?

Ed: Not necessarily. I like certain varieties of discomfort, but hate others. Interactivity, for example, will basically ensure my disdain.

Natasha: You think interactivity is a cheap conjuror’s trick? Or somehow manipulative of the viewer?

Ed: I have a pretty hypocritical relationship with interactivity. Or rather, again, I like it to be figurative rather than literal. It’s not cheap necessarily – but it is often a sleight to cover something hollow. I’m also deeply averse to being cajoled into anything, and I think that’s a good thing.

Natasha: I feel uncomfortable watching high-definition images; they are too real. What does the medium mean to you?

Ed: Very little now. HD has no meaning. How high is high definition? It’s an infinitely shifting parameter. 4k? Pah! How about 8k? The rapacious auto-obsoletion of tech means that definition – both literal and figured – is in flux. But yes, those first digital HD videos were too real. The latest stuff is insane, more than a human can see or something. I suppose that’s interesting – what’s there but cannot be perceived. Or maybe a cat can see it. Or certain cephalopods. My brother can’t see those Magic Eye things; he’s got astigmatism.

Natasha: I’d like to have a drink with your avatar. He seems to be able to hold a few, even if he does go a bit maudlin. How do you relate to him as he’s developed?

Ed: I don’t see him as a him, or a character or anything beyond a cipher or a trope or something. He’s a surrogate who has a purpose to serve. Like an emotional crash test dummy to go through things in my stead.

Natasha: What can I call him? Does he have a name?

Ed: No.

Natasha: So X lives a life you can’t live for yourself? You seem to punish him.

Ed: It’s not a life. This is the problem: an insistent figuration where literalism would be way more productive. And vice versa. It’s not a life, he’s not a he, there’s no name. The pedantry is productive inasmuch as a resistance to the intoxications of the work and the tech yields some residual agency or structural interpretation.

Natasha: You’ve spoken before about the structural conditions that produce the digital image – farms of workers rendering films for instance, or the acres of drives needed to power the cloud. Are you critical of these infrastructures themselves, or their obfuscation? How do you avoid becoming implicit in them?

Ed: Their obfuscation, and again – blah blah – literally and figuratively. And I mean, like, how they are not felt. How their presence is not felt. I’m entirely complicit, but I don’t think that should stop one from talking about something, critiquing it. If you follow that logic, only some coterie of balking puritans could ever disagree with anything.

I need them to categorically align with my determined identity, even if its lack of nuance in no way encounters my reality…

Natasha: X is a white male; the apogee of political incorrectness. Was that important in terms of not appropriating a subject position other than your own?

Ed: Even as the figures are not me, I make those things and make them do things. I need them to categorically align with my determined identity, even if its lack of nuance in no way encounters my reality.

Natasha: Is gender in the digital space of representation reinforced or dissolved?

Ed: That’s a tricky question. Both, I’d guess, depending on the strictures of the particular format, software, corporation or social thing.

Natasha: X feels familiar, steeped in literary history. He reminds me particularly of the existential conquistadors of Romanticism and decadent literature in his sorrowful explorations of selfhood and individuality. Do these inform X?

Ed: Yes it does, though mainly as familiarities, attempts to represent unrepresentable feeling by hyperbolic excess. Sentimentality and purple prose.

Natasha: All of your work is steeped in, and expresses itself through, forms of literature. Sometimes words disassemble into phonemes, clicks, grunts; other times your avatar is incredibly lyrical, at others incomprehensible. Is your approach to language as structuralist as your approach to image making?

Ed: Yes. And similarly tempered

by something like a corporealism.

Natasha: Can you tell me more about corporealism?

Ed: I guess like materialism,

but specifically bodily material.

Natasha: There was an amazing story of non-corporeal language, when Facebook had to unplug their AI program as it had started to speak to itself in a new language. Facetiously, and with my tongue in my cheek I want to ask if you ever worry that your avatar might start to disobey? Would you ever invest him with AI?

Ed: It probably should. Rebel, I mean. But – and sorry to appreciatively swat away your cheeked tongue – it’s not a thing at all; there’s nothing to insert AI into. I could put some AI in my head, maybe, and make different work – work that liberated the figures from their current jailhouse ordering I’ve determined. But that’d be different.

Ethical interaction, lies in the affording of another’s incoherence. To themselves and certainly to you. Unless they or I or whoever chooses to afford otherwise. That’s grace…

Natasha: The thin line between sense and non-sense, language and sound is one that you seem to tread. Is there an expressive potential in this oscillation, one that lies beyond habitual language use?

Ed: I’m not sure what this means. Habitual language use? Most language use is more than that – it’s about making sense, cohering. Coherence is something I’m interested in. Like, where does it lie? Is it an interpretative act more than an intentional, performed one? Is it a violence to cohere something that has neither asked for nor given you the particular tools that might be required to make it cohere? Ethical interaction, I reckon, lies in the affording of another’s incoherence. To themselves and certainly to you. Unless they or I or whoever chooses to afford otherwise. That’s grace.

Natasha: X seems to be aware of his own limitations. Again, a structuralist foregrounding of the nuts and bolts of image, digital apparition, language. Why is this approach important to you? Why can we not get lost in the illusion?

Ed: I guess with a fidelity to corporealism – and its analogue of structure – it’s important to underscore mortality, error, illness, breaks, etc. Limit. And to me, an integrity across form and concept kind of means treating one as the other. The form of the medium shouldn’t be allowed to disappear from view if you’re pushing for a structural apprehension. In the case of the moving image, that kind of means disrupting the illusion, pointing at the thing itself rather than the thing that it’s showing. In my work, I want both to point at each other. Incriminatingly, maybe.

Natasha: Incriminatingly – what’s the fault of illusion? Why should we be suspicious of it?

Ed: Well, neither are true and neither are it.

Natasha: Are your works logarithmic?

Ed: Ooh! Don’t really know what that implies. So I’ll say no.

Natasha: Ha, ha! Well I’m quoting you back at yourself. In an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist you talked about logarithmics, how language begets language. After all, nothing will come of nothing. In what way do your films lead on from each other?

Ed: Wow. I said that? I reckon I wrote that, altering a terrible, garbled answer in a spoken interview. Probably. And maybe the works are all the same work – or another attempt at a sufficient thing that will almost certainly always elude. Like representation? Or resurrection?

Natasha: You’ve mentioned Jan Švankmajer as an influence. I find his animations unnerving, grotesque. Your works hit the viewer through this particular kind of affect. How did you first come across his work?

Ed: On Channel 4 in the UK in the late eighties/early nineties there was a thing called 4Mation, showcasing a world of animated shorts. There was a dance one, too – but it’s the animation one that I remember. Švankmajer was clearly the main event, the most amazing. Then recording his Alice off the TV. Then later Faust. All of it is amazing and I’ve probably stolen anything good of mine from him.

Natasha: Will we remember how to…?

Ed: What?

Natasha: I suppose will we remember anything at all, once our minds and memories are uploaded to the cloud? And if not, how do you make art that’s memorable?

Ed: I don’t know about you but I generally only put stuff up there that I don’t care to think about. As in, I’m left with care, closeness, attention. That’s terrible as regards a wider kind of empathy, I suppose… But maybe the scurf of our culture shifts and we retrieve the loving bodies? Memorable art is the indigestible stuff that nevertheless tastes shockingly metallic.

Keston Sutherland

‘Wake up my fellow citizens and middle class and go look in the mirror.2’ British academic, critic and writer Keston Sutherland is a trailblazer in the field of poetry, whose work demands nothing less than to cause us to recognize social injustice and instigate revolution. His most famous work, ODE TO TL61P 4 (2010–13), is a series of long-form prose poems dedicated to an obsolete product code for a Hotpoint washer. It chronicles the writer’s burgeoning sexuality from youth, juxtaposed with the political and social realities of the UK’s coalition government and 2008 economic meltdown. The collected poems are both tender and satirical, free-wheeling between literary forms, from noise music to tightly metered verse. Sutherland’s use of language is exquisitely rendered, picking up fragments from consumer culture and literary history and collaging these with pitch perfection to frame a Marxist battle cry. High-speed trading, globalized consumption and empty promises of political elites are lampooned with savage grace. Sex, eroticism, pornography and the body are brought provocatively into the syntax of consumer goods and exploitative corporate culture. ‘To be waked to death and faked alive, for the known good or bored stiff rich men whose sexuality is literalized into a rampage of leverage and default swaps, hovering above

Gillian Rose

British philosopher Gillian Rose famously sent her cancer consultant away with a copy of Plato’s Symposium under his arm, having initially asked him ‘How are you going to sell chemotherapy to somebody whose perspective on life is totally erotic?’ For Rose, the Platonic definition of eroticism is the sincere and lifelong pursuit of knowledge; intellectual Eros. Drawing on her fight with ovarian cancer, and loss of a lover during this battle, Rose’s later work Love’s Work saw her justly widely celebrated. The book moves from colostomies to Camelot, love affairs, Auschwitz and its gas chambers, to New York, by way of autobiography and philosophical examination. Cities are mapped to the soul, a relationship of politics to theology. In her explorations of love, friendship and daily existence she posits that within the everyday we can find salvation. NH

Ikkyu

A hero to children in Japan, immortalized in manga, a legendary troublemaker and rascal, Ikkyu was a Zen Buddhist priest, calligrapher and poet, living in the fifteenth century. His verse is by turns ribald and reflective, considering the highest existential questions, and satirizing the religious dogma he saw around him. Iconoclastic by impulse, he furiously opposed hierarchies within Buddhism, materialism amongst its priests, and empty rituals that extinguished authentic spirituality: ‘fucking flattery, success, money. I just sit back and suck my thumb.’

At the age of five he was taken to a monastery in Kyoto to start his training as a monk, where he learned the history of literature and poetry. Seeking the true zazen (meditation-orientated Buddhist practice), he moved from master to master. He was known to drink heavily, and visit prostitutes as part of his quest for enlightenment, and spent years travelling as a vagabond, moving between poet and writer friends. At once irreverent and zealous, his poetry treads a similar line to his life. NH

Julia Kristeva

Bulgarian-French philosopher, critic, feminist and literary critic Julia Kristeva is known for her work in structuralist linguistics, psychoanalysis, semiotics, and philosophical feminism. She explored the concept of abjection in her seminal book, The Powers of Horror, 1980. In her formulation, informed by psychoanalytic theory, the abject refers to a breakdown in meaning stimulated by a failure to differentiate between ourselves and otherness; a disruption of the division between subject and object. For instance, to encounter a corpse forcefully reminds us of our own mortality. Abject bodies, such as those punctured by a wound or seeping pus, or indeed broken objects that have been cast off as trash, break down normative orders and threaten status quos. They are excessive, out of control, and overwhelm the clean, moral, and pure. They are bodies through which the real erupts into our lives, particularly in relation to ever-looming death. In this the abject is strongly affective, making a visceral and unmitigated appeal to our deepest sense of self, and order. The term was popularized in the art world in the 1990s, particularly in relationship to feminist artistic practice, in which the abject body of the female provides a rupture in the continuum of patriarchal society. NH

Jan Švankmajer

‘Surrealism isn’t dead! Support imagination!’ So ends the fundraising video for Jan Švankmajer’s Surviving Life; Theory and Practice. The imperative cuts to what drives the Czech filmmaker’s work. Švankmajer’s surreal and wonderful animations have charmed and unsettled audiences for decades, offering another version of reality – and have repeatedly gotten him into trouble with censors. Having trained at the Marionette Faculty of the Prague Academy of Fine Arts in the 1950s, he moved into theatre, before choosing film to create macabre and uncanny animations featuring severed limbs and possessed dolls; giving life to the inert, and spinning the everyday into a surreal amplification of itself. The output is prodigious, and Švankmajer is also recognized as an artist, exhibiting drawings, collages and ‘tactile sculptures’. These were produced mostly in the mid-1970s, when he was banned from film-making by the Czech authorities for having mixed fact and fiction too convincingly in his film Castle of Otranto – he used a real journalist to play a journalist protagonist. As a card-carrying member of the Prague Surrealist movement, his work is duly informed by visions, dreams, nightmares and alternate realities. His film adaptation of Alice in Wonderland is the perfect subject matter in this regard.

He is not without humour, albeit dark. Surviving Life; Theory and Practice, a feature-length work which he jokingly calls a psychoanalytic comedy, chronically lacked an adequate budget. Responding to this problem he made the film using paper cut-out animation throughout; instead of paying actors’ fees he used photographs, and saved money on catering because ‘photographs don’t eat’. NH

- A Tumour (In English), Ed Atkins, 2011

- ODE TO TL61P 4 (2010–13)

- ODE TO TL61P 4 (2010–13)