Coming of age is the most exquisitely painful of life’s many transformations. It’s a period of heightened sensitivity to the world and bewilderment at the eruption of desires beyond our ability to control. We realise that the identity supplied to us by our parents no longer fits, so we try on new ones; we experiment with sex and drugs in attempting to channel the desire that attaches itself to whatever and whomever it chooses. We satisfy some urges and we sublimate others, half-conscious that these processes will shape our personalities forever. Not knowing where the boundaries are, we overstep them.

And so the coming-of-age novel takes us down the path that separates innocence from experience, describing the obstacles that litter it. Because the process of finding oneself tends naturally to self-indulgence and introspection – as any teenage diary will attest – the coming-of-age novel is often related in the first person, is frequently a writer’s debut, and is often characterised by angry or joyful rejection of the old authorities. As such, it is responsible for some of the most recognisable voices in fiction: Alex in A Clockwork Orange (1962), Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in the Rye (1951), Esther Greenwood in The Bell Jar (1963).

The sudden infusion of the world with desire means that the coming-of-age novel must also always be erotic. I don’t mean by this that its pages must filled with sex – to reduce eroticism to the satisfaction of bodily needs is to miss the point – but rather that its style must always embody the ecstasy and suffering of initiation into adulthood. It’s an experience that only the most gifted writers can capture.

BONJOUR TRISTESSE 1

I was a brattish sixteen-year-old when my French teacher told me to stop coming to lessons I was determined to disrupt. Instead, she gave me a stack of French-language classics and told me to come to her house when I was ready to discuss them. Against the dark glamour of Flaubert and the existentialists, Bonjour Tristesse was like a pop song by one of the 1960s’ chanteuses. Written when Sagan was just nineteen, this story of sexual jealousy is as sad as the title would suggest, but the bolted-on moral can’t disguise the bright beauty of the prose. It’s perfect like a yellow jumper on a redheaded girl.

GIOVANNI’S ROOM 2

Liberation is painful, and no one writes about suffering and release like James Baldwin. It’s in every sentence of this story of a young American man in Paris who must come to terms with the consequences of his bisexuality. A favourite of the Berlin-based writer Alan Murrin, this is an expression of psychological torment – the opening line informs us that this is the worst day of the narrator’s life – realised in prose of astonishing beauty.

ALMOST TRANSPARENT BLUE 3

The relation of pleasure to pain finds a direct expression in Murakami’s notorious novel, recommended to me by publisher Jacques Testard, about crossdressing, gender-bending, extremophile teenagers. It’s a frequently uncomfortable read, but Murakami faithfully represents the exhilaration of transgression and the freedom of self-destruction expressed in violent orgies and ruinous drug abuse. In the risks taken by its protagonists, and the resemblance of their hedonism to nihilism, it is a reminder that our sexual awakening is generally coincidental with the first felt awareness of our own mortality.

SWEET DAYS OF DISCIPLINE 4

‘It happened one day at lunch. We had all sat down. A girl arrived, a new one. She was fifteen, she had hair straight and shiny as blades and stern staring shadowy eyes.’ No coming of age is complete without at least one obsession for a classmate, and Fleur Jaeggy’s novella takes us through the degrees by which such fixation can shade into derangement. I was alerted to this book by the novelist Stephanie LaCava, whose own writing explores the dark impulses underlying adolescent identity formation: in this case how our narrator defines herself by imitating and then destroying the objects of her desire. All this in prose that glitters like a razor’s edge.

ON EARTH WE’RE BRIEFLY GORGEOUS 5

To come of age is to learn how to tell a story about yourself. This becomes the story that we tell others and that we must continue to tell ourselves. Few novels in the 21st century have expressed this principle so effectively as Ocean Vuong’s letter from a son to his mother, in which the narrator must find a way to bind together all the threads of his personality in a way comprehensible to her. Vuong is a poet, and the effect of this book is from the sensuality of its language as much as the details of its plot.

THE RAVISHING OF LOL STEIN 6

The plot of Duras’ debut novel – which I picked from Quinn Latimer’s bookshelves – is barely there: a young woman suffers a sexual humiliation that, years later, manifests in her obsession with spying on a friend during her trysts. In withholding a great deal more than it reveals, it fills the first principle of the erotic even as it traces the scars of thwarted adolescent love. This strange and unsettling novella feels like glimpsing your first lover through a crowd: your heart leaps and falls before you register the cause, and the feeling will linger for weeks.

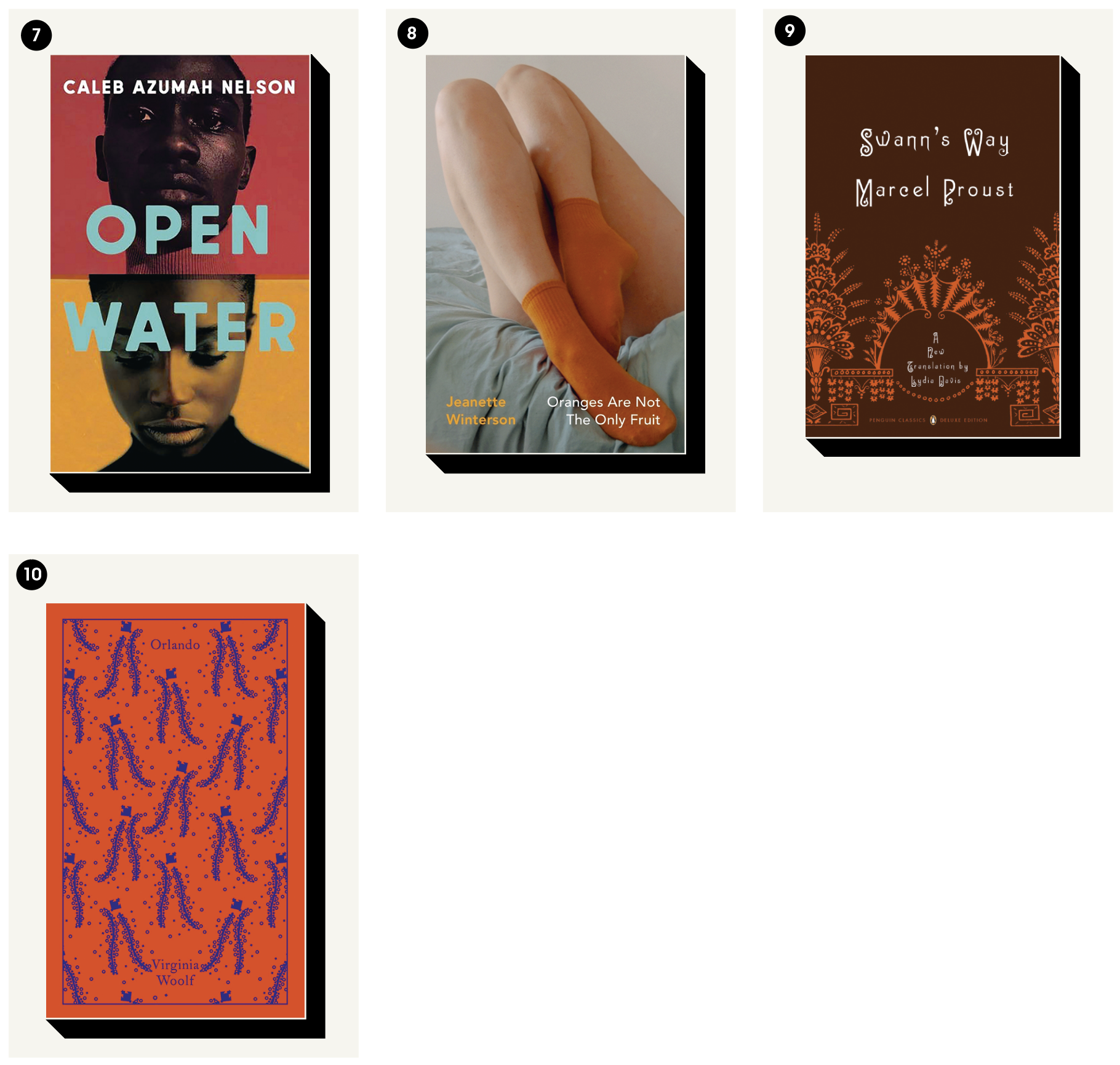

OPEN WATER 7

Men and women on the cusp of adulthood pick up guitars, pens, cameras and paintbrushes to give shape to new feelings (no matter that most of what they produce is – and I don’t except my teenage self – lamentable). In this beautifully executed evocation of that time in one’s life when everything is extraordinary, the author links the blossoming of the artistic impulse to the evolution of a love affair between a photographer and a dancer. Recommended by the biographer Francesca Wade, this book is intensely physical in its descriptions: the narrator describes with obsessive precision the way a lover winds her legs around his, for example, so that the reader can almost feel the charge between their bodies.

ORANGES ARE NOT THE ONLY FRUIT 8

The best coming-of-age novels are often coming-out novels. Winterson’s rapturous debut tells of a teenage girl who, having been raised in the evangelical Christian tradition by her adoptive parents, falls in love with one of her converts. In its appropriation of religious themes to tell the story of lesbian awakening, Winterson’s influential debut is among the strangest and most powerful in a crowded field. It is also infused with the rebellious spirit of many of the best books in the coming-of-age genre: a fuck-you to the constraints set by parental authority in favour of the world – expanding possibilities of love and desire.

SWANN’S WAY 9

When I asked the writer Orit Gat for the greatest coming-of-age novel, she felt forced to give me ‘the most pretentious answer ever.’ The problem was that the pretentious answer was, she pointed out, the right answer. It’s hard to argue with her, and if the several thousand pages of In Search of Lost Time seem daunting, then seek out Lydia Davis’ brilliant translation of its first volume. This story of a young man making his way in Parisian high society is the most ambitious gossip novel that’s been written, with tales of cross-dressing, wet dreams and lesbian sex scenes rendered in the most skin-prickling prose ever committed

to paper.

ORLANDO 10

Suggested by the artist Eloise Fornieles, this is the greatest story ever written about failing to come of age. The hero of Woolf’s most playful novel lives for 300 years, never ages, wakes up in Constantinople to discover he is a woman (a shift which Orlando takes entirely in her stride), takes lovers of both sexes irrespective of Orlando’s own, never succumbs to boredom, never grows up, never tells anyone what to do with their bits, writes lots of poetry and never settles down. This, perhaps, is the coming of age to which we should all aspire.