A fence closes the entrance to the Erocity building on the Kuiperskaai, Ghent.

fig 1:

Erocity

On 19 March 2015, the Flemish tabloid Het Laatste Nieuws reported some alarming news. The last peep show in Ghent (Belgium), Erocity, had gone bankrupt and was forced to close its doors. It was only one of the many peep shows that went out of business over the years. Even in Amsterdam’s red-light district, the self-declared capital of vice, which seems to function as one of the main engines of the tourist industry, only one institution from the 1970s still remains: the Sex Palace Peep Show. Peep shows have clearly become a relic of the past. Almost gone is the mixture of excitement and nervousness when trying to sneak into the establishment, staring at the always very flattering picture of the girl and waiting for her number to appear on the screen. Meanwhile killing time by feigning interest in butt plugs, dildos and condoms in flavours you could never imagine, before rushing to an empty cabin when she’s up, dropping the coin in the slot and the window slowly opening to reveal the girl stripping and dancing. There is a bit of teasing involved when she approaches you, pushing her buttocks – or other body parts – against the glass. So close, yet untouchable. Plato would have loved it. She keeps prolonging the excitement until the tragic moment arrives and the window slides down again, leaving you with the eternal question: are you going or staying for one more? Or heading for a private show in a separate room? For some more money, you enter a cabin slightly larger than a phone booth. There you sit on a low couch opposite the girl, separated by a pane of glass that goes from floor to ceiling. The girl dances for you behind the glass and judging by the smelly toilet paper overflowing from the basket and the stains on the séparé, you were not the first visitor today. On your way out, you pass the janitor, the guy with the unenviable job of cleaning up the mess the customers leave behind.

Peep shows increasingly seem to belong to an obscure ritual from the past. The legendary dirty old men in long raincoats have been replaced, mainly by groups of curious tourists, including giggling teenagers or couples trying to spice up their love life. The reason for its decline and impending demise is pure and simple: the internet. With the abundance of readily available material, people no longer bother going across to the other side of town, at the risk of bumping into an acquaintance when entering or leaving the establishment. Hence, the experience of the peep show has been superseded by webcams, the glass replaced by a computer screen with girls dancing for you, while you never have to leave your lazy couch. The whole experience has become virtual and less tangible, the payment electronic, sometimes mimicking the sound of a coin falling into the slot. And like most things on the internet, the choice is infinite. There are plenty of girls and you no longer have to wait to see the one you like performing. Everything seems more accessible and varied than ever; meanwhile an entire ritual, together with a sense of longing and guilt, has disappeared.

Leon Battista Alberti 1404–1472 Polymath – Architect – Sculptor – Painter and Theoreticia

fig 2:

Leon Battista Alberti

It is unsurprising that internet porn has killed the peep show. Indeed, the sex industry has always been very quick to embrace and adapt new technologies. Whether the development of photography, film, VCR, Blu-ray or virtual reality, the porn industry has often been a pioneer. The phenomenon of the peep show also emerged from another kind of cultural practice. Peep shows or peep boxes were originally used by travelling showmen who provided entertainment to an excited crowd that gathered round.

One of the earliest examples dates back to the fifteenth century and was created by the gentleman and typical homo universalis Leon Battista Alberti. Alberti wrote the revolutionary treatise on art Della Pittura and made boxes to illustrate the principles of perspective. These boxes became increasingly popular in the seventeenth century as a means of creating the illusion of three-dimensionality by manipulating the perspective of the view, usually of the interior of a room. Imagine a wooden box with holes through which one views a series of pictures set in motion. This phenomenon also existed in several cultures, from the Chinese – scenes go back to 1874 – where the phenomenon was called ‘pinyin’, to Ottoman Syria where it was known as ‘sanduk al-ajayib’, which literary means ‘wonder box’. Storytellers carried these so-called wonder boxes on their backs, showing scenes from heaven and hell, together with exotic landscapes and animals. Before the turn of the century, the erotic potential of these boxes was also being explored. Films were presented in a freestanding machine in which one had to deposit a coin.

fig 3:

What the Butler Saw

In the early 1900s, the film What the Butler Saw was quite a hit in England. It was shown on a device called a ‘mutoscope’ and featured a partially undressed woman in her bedroom. Hence, the viewer found himself in the position of a peeping Tom, a butler peering through the keyhole. Bedroom Secrets from the late 1920s also became a success, showing women in various states of undress. These films were produced by the Mutoscope Reel Company and sometimes even had the option to pause the image – always handy. Over the years, the footage and machinery became increasingly professional. Eventually, the devices were replaced by performers of flesh and blood in live action. The phenomenon of the peep show as we know it was born. This reached its peak in the 1970s when peep shows became an essential part of red light districts. But according to their many detractors, they also attracted crime – though sociological findings bring that into question.1 Times Square, back then the dirty underbelly of New York, was once teeming with porn theatres and peep shows, trying to lure passers-by inside with the phantasmagoria of flickering neon lights. ‘Girls! Girls! Girls!’, ‘XXX’. But that was before the mayor/crime fighter Rudy Giuliani – advocate of the broken windows theory which says that a site of graffiti or urban disorder should be fixed as quickly as possible as it may lead to more serious crimes – cleaned up these places of debauchery in the mid-1990s. Some of the venues became real classics, like the Lusty Lady, with branches in San Francisco and Seattle – both since closed down – and that was the first unionized sex business in the US.

fig 4:

Panopticon

Early peep boxes were a form of pre-cinema. Moreover, the phenomenon of a peep show is very cinematographic in itself and has featured in movies as a meta-reflective act of watching people watching people and the entire world that goes with it: dodgy types and flickering neon lights. The similarity between the glass window and a TV screen – or later a computer screen – is just too obvious to ignore. Peep shows are all about the gaze and the question of control. Men – or the occasional woman – in cabins watching a woman on a revolving dance floor, or in a larger room where several women dance in a space clad with mirrors, like in the Lusty Lady in Seattle, which featured in the movie American Heart (1992) with Jeff Bridges. What remains intriguing is that the dancer can also see the viewer, creating a voyeuristic tension. The circular architecture of most peep shows, with a central space surrounded by cabins, almost recalls the panopticon, a typology developed by philosopher and social reformer Jeremy Bentham in the late eighteenth century and which is still used in many prisons. Built around a central area, the model allows inmates of an institution to be observed while they are unaware that they are being watched. In the peep show, however, there is a double gaze. The similarity with a prison is reinforced by the cabins that almost look like cells, where viewers lock themselves up – voluntarily – as prisoners of their own desires for the duration of the performance. In the private cabins, the comparison with a cell is also evoked by the use of an intercom by which the performer and visitor communicate, similar to the device used by an inmate and a visitor, who are equally separated by a glass partition. Such a device also plays a role in a brilliant scene in Hardcore, the 1979 movie by Paul Schrader that never really received the critical acclaim it deserved by press and author alike. In this drama, shot in a typical 1970s granular quality, Jake Van Dorn – a no-nonsense Calvinist businessman played by actor George C. Scott, who had a serious drinking problem which did not make the shooting any easier – searches for his teenage daughter who disappeared on a church trip. With the help of a private detective, Jake discovers that she is performing in a pornographic movie – called The Slave of Love – so he decides to search for her. Trying not to appear too out of place, he wanders through the seedy red-light district of Los Angeles with sunglasses and a tacky floral shirt, going from strip clubs to sauna parlours, brothels, peep shows and sex dungeons. The atmosphere is suffused with red and purple hues – the kind of stuff that must have made Schrader’s fellow director John Cassavetes jealous – the protagonist’s malapropos and alienation are expressed by the distorted soundscape. Jake can barely conceal his disgust for this lifestyle, which contrasts so strongly with his religious beliefs. When he hears that the porno actress Niki may know where his daughter is, he visits the peep show where Niki works. It is a highly cinematographic scene that uses the setting and the confinements of the glass-separated private booth to the full. When Jake enters a room bathed in shades of red, he opens a big velvet curtain that leads to the cabin. The floor is littered with pieces of toilet paper and there are several stains on the window – one can imagine what these are. Jake puts a coin in the slot and up goes the window. Soon a naked young girl arrives, nonchalantly finishing her conversation with an equally naked colleague. She sits down on a chair abruptly, picks up the phone, points at Jake to do the same and immediately opens her legs wide. The scene is shot in such a way that the camera is slightly too high for the viewer to see her vagina, which remains hors champ. Jake, however, has a full view – or beaver shot, to stick with the professional jargon – which doesn’t seem to distract him at all. On the intercom, he questions her about his daughter. At the moment when Jake asks the stripper if she knows where his daughter is, the window slides down, brilliantly toying with the tragedy of the closing window and using it as a suspense-creating device. After inserting another coin, they agree to leave together on a trip to find her, their quest leading them to the underbelly of San Diego, with more visits to strip clubs and peep shows on the menu and even a little theological discussion in between. They do eventually find the daughter, although the journey is more interesting than the final destination, especially in cinematographic terms, leaving a touch of disappointment and frustration in the mind of the viewer – without the need for a spoiler alert.

Travis is sitting in one of the peepshow booths in front of the mirror

that becomes a window as Jane comes through the door and switches on the light

fig 5:

Paris, Texas

The 1984 film Paris, Texas by Wim Wenders also features a scene with a peep show magnificently used for cinematographic purposes, as it transforms the double gazing into a truly sensory experience. Travis, a man suffering from amnesia, is desperately searching for his ex-wife, played by the stunning Nastassja Kinski. He follows her and discovers the strip club where she works. Here, the architecture is completely different to the peep show in Hardcore or American Heart. There are several booths, not arranged in a circle, but on both sides of a corridor, thickly carpeted and decorated with fake plants, turning the space into an illusory ‘dream factory’. There are no doors that can be locked, but heavy purple curtains. The private booths are not as spartan, dirty and seedy as in the average peep show, such as the one in Hardcore. Every room has a different theme and the customer can choose which atmosphere and type of lady he desires – like an erotic theme park. The assortment of decor ranges from a poolside to a hotel or café, and the archetypal ladies include nurses and waitresses. Each room has a particular aura, awakening the visitors’ desires, an illusory dream created and simulated only in the guests’ areas. Through a large window he can see the girl in the setting of his choice, as if staring at a giant TV screen. From her side, the girl can only stare at her own reflection in a mirror that sits in a wooden frame, stuffed with insulation material that has been installed rather clumsily. When Travis enters the first room – the poolside – and calls for a blonde girl, hoping for his ex, who he spotted earlier at the bar, a nurse walks in. When he notices that she’s looking at the wrong side, he says: ‘Why don’t you look at me? I’m out here. Can’t you see me?’ The woman replies: ‘Sweetheart, if I could see you, I would not be working here’. There is no double gaze here and hence less control; for many performers, like this one, it must be a relief not to see the customers. When Travis changes rooms, going to the one that evokes a hotel room, with attributes including a pink lamp and red phone, he spots his ex-wife. When she walks in, he doesn’t even look up, but just listens to her voice through the intercom. Silence ensues. Travis has nothing more to say and ignores her questions. ‘You realize I can’t see you, though you can see me,’ she says. When he aggressively asks if she can also meet her customers afterwards, she loses her temper. He apologizes, puts the phone down and leaves. When he returns later, he meets her in a room that’s supposed to look like a kind of restaurant, including a blackboard with the price of meat love – which goes for $3.95, by the way – and coffee. He starts talking to her through the intercom, and immediately turns around to avoid her gaze. The sensory experience is no longer visual but auditory. Travis tells her the story of a couple and the way their relationship went sour. Little by little, the woman starts paying attention and becomes increasingly intrigued. As soon as he mentions that the couple lived in a trailer, she has a sudden flash of insight, recognizes his voice and starts crying. The next shot shows her reflection in the mirror with the messy insulation material, shattering the illusion of the dream world and leading to an epiphany. She starts caressing the glass, exploring the physical dimension of the barrier that separates them and which is so crucial for a peep show. As they touch each other’s hands through the mirror and stare at each other, their faces almost blend into one another. He asks her to switch off the light, so he can see her. With the illusion gone, reality enters. The drama reaches a climax when she doesn’t want him to go and bangs on the window to call him back. Heart-breaking cinema.

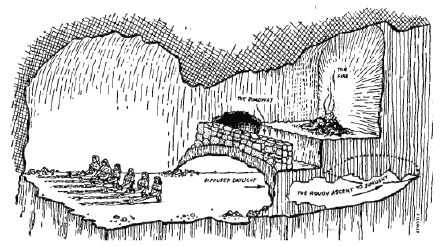

Plato’s allegory of the cave

fig 6:

Plato’s cave

What we are watching here on our TV – or computer screen – is a man and a woman looking at each other through a screen, unsurprisingly rather similar to ours. It becomes a mirror image, reminding us of the illusory nature of cinema. Art, and more specifically cinema, is a reflection of reality. It is often linked to the metaphor of Plato’s allegory of the cave, the image that the Greek philosopher chose to evoke our restricted view of reality. Plato used the idea of prisoners chained to a wall in a cave with a blank wall in front of them. The people watch shadows projected onto the wall from objects passing in front of a fire behind them. The same image could almost be used for a peep show. Locked up in small, dark cabins, like the prisoners in the cave who see only the shadows on the wall, the visitors peep through a glass window or hole to see a reflection, an illusion of reality in the shape of a naked woman dancing for them, evoking a dream world or phantasmagoria – which is even more the case in the kind of peep show in Paris Texas. It offers a brief glimpse before the little window slides down again irreversibly, leaving the client alone in his small, dark cabin. A place to lock yourself up temporarily and free yourself from the arousal of desires before returning to the reality of the outside world.