Exposing one’s body to the risks of close proximity with others – together with the precarious state one’s system of beliefs enters into – is often life-changing. At the very least, the experience is an entry point to a better understanding of oneself. In this Sugar Rush feature I reflect on desire and eroticism as ways to access alternative notions of precarity and the body as a ‘site of common human vulnerability,’ as Judith Butler puts it in her book Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Volience (2006). A possible counter-narrative to the ‘fear of the other’ mentality, ever present in political discourse. The following choir of voices has been arranged to explore the sense of anticipation, vulnerability, and erotic potential that comes when encountering someone whose position is diametrically opposed to one’s own.

One work of art that evokes this ‘dangerous exposure’ in an incredibly profound and complex way is the 1974 film Conversation Piece by Luchino Visconti. It explicitly centres around the desire to meet that ‘other’ as a way to expose oneself to the precarious state of danger that inevitably leads to self-knowledge and, possibly, the death of who we were before it. The main character is an American professor, played by Burt Lancaster, whose isolated life as an 18th century painting collector and connoisseur was shaken by the arrival of a nouveau riche marquise (played by the glorious Silvana Mangano), her rebellious German lover (Helmut Berger), as well as her daughter and boyfriend, all who rent the professor’s upper floor apartment in a palazzo in the centre of Rome. Their taste for modern art, unconventional sexual practices and discom-bobulated liaisons clash at first, but later evolves into a questioning of the professor’s certainties and desires. In this surrendering protagonist, many read a self-portrait of Visconti, who died only two years later and directed the whole movie from a wheelchair, orchestrating the acting as a stage director, with the very theatrical setting subsequently furthering the film.

The role of the professor’s beloved conversation piece paintings is an apparent reference to art historian and collector Mario Praz who significantly contributed to the decoding of this genre of paintings in art history. Believed to be a simple still life with human figures, Praz’s 1971 book Conversation Pieces: A Survey of the Informal Group Portrait in Europe and America sheds light on how the depiction of different family groups during indoor or outdoor activities are key to understanding the social milieu that produced them.

That depiction reinforces the idea that artworks are privileged ways to access society and its ever-changing rules and constructions. Visconti’s luxurious mise en scène portrays the incredible impact of Conversation Pieces on the imagination of many artists, and that led me to use this cinematic reference as an expedient for this feature.

Within this Sugar Rush, different contribu-tors brought a fragment to a contemporary portrait of these kind of encounters, quests of identity and unstable relationships, all efforts made in the attempt to understand ways of relating to each other. Together those voices form a present-day conversation piece, in which the precarity of the self meets the sensuous. By inviting the participants to reflect on the influences and concerns orbiting Visconti’s film, I’d like to mimic the sort of remote stage orchestration that gave way to the film.

Övül Ö. Durmusoglu

What does it mean to become family? How do civic modern individuals perform their role? The professor in Conversation Piece is an avid collector of the genre from which the title takes its name. He is introduced to the audience while carefully inspecting an Arthur Devis painting, a well-known painter of the genre. ‘Conversation pieces’ are repetitive visual tools constructed by artists that depict middle-class aspirations and convey information about social membership. Visconti’s love and hate relationship with the bourgeoisie is echoed in the professor’s love and hate for his new family. As the film unfolds the audience is confronted with what is forbidden or suppressed within the frame of painting; lies, secrets, betrayal and incestuous love.

Conversation Piece reminds me of Ask-ı Memnu (Forbidden Love), a novel published by Halid Ziya Ucaklıgil in a serial form in Servet-i Fünun magazine in 1899 and adapted for television in 1975 and 2009. In the novel, a charming young woman, Bihter, marries a rich widowed aristocrat and slowly falls in love with the young and handsome Behlul, a distant relative that lives with the family. As Bihter and Behlul consummate their passion for each other under the same roof, Bihter’s mother realises and intervenes by encouraging the platonic love of Nihal, the daughter of the widow, for Behlul. Behlul and Nihal’s becoming a real couple and their decision to marry triggers Bihter’s suicide, collapsing the whole family. Forbidden love became a frequent theme in late Ottoman literature while the society demanded new forms of democracy appearing in European countries to be adopted in the Empire. Therefore, one wonders about the socio-realistic connotations of ‘forbidden love’ at such a turn. Is the desire for the new that comes from the outside always forbidden and treacherous? After a decade of its broadcast, the contemporary adaptation of Ask-ı Memnu is considered as a classic and the actors who played Bihter and Behlul, respectively Beren Saat and Kıvanç Tatlıtug, are perceived as the most attractive couple in recent Turkish television history. When the final episode aired in 2010, the streets of Istanbul were silent, everyone waiting for the well-known tragic ending of the novel mourning for Bihter.

The erasure of the strong and rebellious female figure, ready to sacrifice for love, is the elephant in the room in Ask-ı Memnu. Following her heart and desire, Bihter counters the norms of the bourgeois family that is ready to continue its life with its lies, secrets and betrayals. With the conservative turn and the ideological pressure it exerted in the daily life of Turkey after 2010, it is not possible to encounter characters like Bihter on television anymore. On the one side, the forbidden love she represents is seen as the obvious degeneration of Western-style bourgeoisie by the new fundamentalist rich circles. A fake value system is supported and performed. On the other, there is a silent collaboration between two seemingly polarised bourgeois forms or power and their fake value system, which makes it almost impossible for figures like Bihter to breathe.

Pedro Gómez-Egaña

I met an insomniac man in his early thirties who can only sleep when he’s in a busy public place. Park benches, yes, but also underground stations, buses, museums, concert halls. The noisier and busier the deeper his sleep. At dinner parties he is known to wait until after dessert to slide under the table and fall asleep so deeply that no one dares to wake him. He fakes being drunk at dance clubs just so that he can pass out while people are bouncing around him.

When he isn’t out in the world sleeping, he is inside his home being restless. He is a solitary guy, and a neat guy. He cooks and cleans up immediately after the food is ready and before he sits down to eat. He knows that exhaustion is useless for somnolence, but he goes to the gym anyways, and runs on the treadmill until the effort brings a promise of drowsiness, but not so much that it will render him useless. He hates inopérance. He learned French at home at night. It took him three months.

When he told me of his habits, he also told me that when he finds a place to sleep, and as he begins to make himself comfortable amongst a crowd, he immediately gets an erection. It’s the same kind that he used to get as a teenager in the mornings, the classic ‘morning wood’, except now he gets it before and not after sleep. Now it turns out that this is the only way he can get an erection at all. Porn, random

encounters, lovers, fantasies, none of them trigger his body anymore. Only the imminence of public sleep.

Since for my work I’ve been researching different kinds of sleeping routines, I asked him if I could come to one of his public naps and observe. I’m fascinated by the fact that busy places could have this simultaneous effect of extreme relaxation and unique arousal. He agreed. I imagined he would suggest we go to a train station or something like that, but instead he invited me to a party that he is attending on New Year’s Eve. He had been looking forward to it for months. He could try to get me a ticket. I have a soft spot for unusual ways of celebrating dates like Christmas and New Year’s so I said yes.

Today is 30th December and I am writing this on the plane on my way to Berlin where me and this guy will meet. I confess that I’m not really sure exactly how to carry out this observation. I don’t know how to deal with myself around him and how to be during the party. I wonder if he is an exhibitionist. I wonder what he is expecting. I wonder if he has a plan. I wonder if my presence will make the sensation even more pleasurable for him. I wonder if this has anything to do with pleasure at all.

A space engineer once described orbiting as ‘the intricate administration of a perpetual fall’. He said that if you have the right angle and the right propulsion, an object can fall and keep falling. The shape of this delicate balance is a long curve around the Earth: an orbit. I guess the sensation between arousal and sleep might be somewhat like that. The body lighting up with desire at the very moment it drifts out of consciousness. Any sense of physical direction getting lost, giving way instead to a thin tension, a round edge, a spiral.

The pilot just spoke. We’ve started our descent. The landscape will be much darker once we land so we should enjoy the views from up here. I love it when pilots are romantic about flying. The engine’s just slowed down and the nose of the plane is dipping slightly. We can all feel the drop in our gut. It feels good. It will be nice to finally land, but I also feel that deep inside we are all so sad that we can’t just stay up here forever.

Ana María Millán

‘July 3: I have cooked. The day before yesterday I slept with a guy, I’ll call him Maarten. It was as if I were home again, sex, chit-chat, laughing. No idea if anything will come of it. He is a bit of a womaniser and we didn’t make any plans. Besides, he’s popular with the women, he’s very good-looking. So I’m not expecting too much, I’m staying cool. Never thought that I would find love here. I see myself alone forever so every hook-up is an added bonus. Besides, and I haven’t written about this before, it’s possible that they’ll send me away, they already told me three times that a comrade was looking for me to send me on the road. He seems to have changed his mind, but he insinuated that he was only doing it for the moment and that it would be my turn in a month. Somehow I believe him. I’m sure I’m ready. To restore myself, to absorb a bit of culture, to be in a different environment. At first I thought I wouldn’t be able to, but now I believe I can. Finally do something useful. I can survive the loneliness, I survived Spain and that was really a hard experience. And who knows, maybe it’s outside Colombia.’

Tanja Nijmeijer

Tanja Nijmeijer (born 13 February 1978), also known as Alexandra Nariño, is a Dutch former guerrilla fighter and English teacher who has been a member of the Colombian guerrilla group Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) since 2002.

She has also been one of the group’s leading public figures since the discovery of her diary in 2007. Nijmeijer was part of the negotiating team involved in successful peace talks with the Colombian government.

Otobong Nkanga

Escape, 2018, acrylic and crayon on paper, 29.7 x 42cm.

Courtesy of the artist and Mendes Wood DM, Brussels.

Olaf Nicolai

Images from the three-part book: Olaf Nicolai, Maria Colao: A Bibliography, Conversation Pieces, Conversation Pieces/Mario Praz, Cologne, Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2008.

Conversation Pieces was developed as an artistic work based on the idea that a bibliography of books and a private house can form portraits of their owners. The library of Maria Colao served as a starting point, she founded the gallery Primo Piano in Rome in 1972. After she died in 2003, the approximately 2,600 volumes in the library were united in a bibliography published under the title Maria Colao. A Bibliography. The house in the pictures is Mario Praz’s, a 19th-century style that Praz himself designed as a personal statement. An installation by Nicolai is presented within the library, with the kind of small frames usually used for personal souvenir and family photos from the reservoir of Colao’s books. Themes include autobiography as work of art, remembrance as resource, art as living space and collection or fetishism. There are also reproductions from Mike Kelley’s Three Projects (Pogo The Clown) and Robert Mapplethorpe’s Portrait of Sebastian Fernandez, presented in an idealised version of a room for a child where none ever played.

Tala Madani

Dripping flowers, 2016

Courtesy of the artis and Pilar Corrias Gallery, London

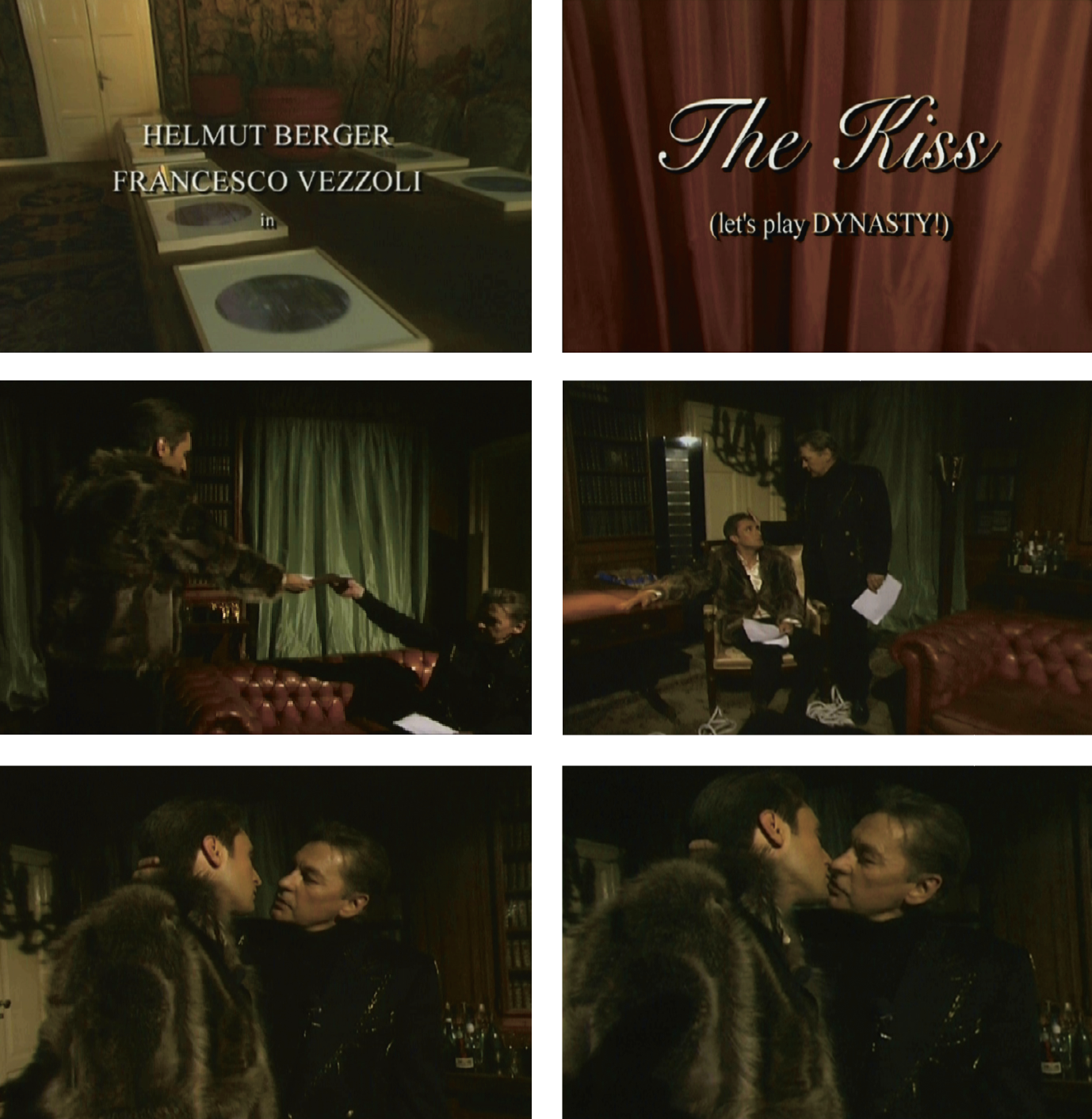

Francesco Vezzoli

Francesco Vezzoli, The Kiss (Let’s Play ‘Dynasty’!),

2000, video, colour, sound, 5:20min

Courtesy of MAXXI, Roma

The White Shore, the Black Shore

Sir Captain, Please stop here!

I’m so tired. Yes, I’ll stop.

Be careful! They’re firing! Stay down!

I’ll be careful, but protect yourself too!

Tell me then, soldier, where are you from?

I come from a country near yours…

But on the river there is the border

The white shore, the black shore

And on the bridge I can see a flag

But it’s not that which is in my heart…

Sir Captain, I have to go!

I’m coming with you… You cannot leave me!

No, I will not leave you. I already know it…

I’ll be next to you forever…

‘The White Shore, the Black Shore’ is the English translation of the Italian song La riva bianca, la riva nera, performed by Iva Zanicchi.

Ula Sickle

Vilém Flusser, Minneapolis Gestures, University of Minnesota Press, 1999.

‘We don’t pay attention to most gestures because we don’t pay attention to what is familiar, and so when we concentrate on them, they seem new and surprising. But we don’t see the gesture of loving because social pressure demands that it be private, and private is by definition invisible, and if through some counterforce it becomes public, then it appears to be a controversial gesture, obviously changing its character, which has nothing to do with exhibitionism and ostentation. In the gesture of loving, we have one of those few gestures (other examples are flag waving and saber rattling) that appear on posters everywhere, in newspapers and television programs.

It is the task of phenomenology to strip the appearance of exhibitionism away. Only the gesture of flag waving is motivated by exhibitionism. It is pornographic at its core, and the task of phenomenology is to expose the exhibitionistic core behind the exhibitionistic pose. Meanwhile, exhibitionism in the gesture of loving, to which we are currently far more exposed than we are to that of flag waving, makes the gesture seem strange. The task of phenomenology is to show that it is not pornographic and so to expose the core of the gesture, which is in danger of being lost.’

Heman Chong

Anna Rispoli

Blind date. The audience is invited to a mysterious location, where they will discover the script of a conversation based on transcriptions of nine interviews. No actor is going to play the text. It will be up to the spectators to give voice to the discourse of nine unknown Brusselairs, discovering their different perspectives on love and eroticism while savouring the words in their mouths.

ELLA: I’m a physio in a centre for people with disabilities and am in my fifties. I help couples with disabilities have sex. I love wearing bright clothes, often patterned, in all shades of red and purple. When I’m in love I feel like the sexiest women on the planet!

TAHEL: I’m interested in what it’s like for you to help other people get intimate. (Short pause). Cause you actually do it with direct personal contact, don’t you?

ELLA: Well I really see myself as an assistant there. Because I only do it with disabled people, or people who can’t really do it physically the way they’d still like. So like, if a woman would like to touch her partner, wants to touch his penis and would like to stroke it, but can hardly do that at all anymore, or if he wants to touch her breast, but can’t – things like that. Then I take his hand and spread his fingers, so he can place it on her breast. Or if she wants to touch his penis, play with his lingam, then I just make sure that the catheter tubes are out of the way first, so we don’t accidentally rip out a catheter. Can easily happen in the heat of the moment, right? That’s not very nice, um, or like when I see she doesn’t have any strength left, she, so she can’t take the lingam at all anymore, so he might even still…

TAHEL: Wait a minute: can you explain ‘lingam’?

ELLA: Penis.

This is an excerpt from the performance Your Words in My Mouth. Brussels Take by Anna Rispoli, Lotte Linder and Till Steinbrenner.

Lukas Dhont

Laure Prouvost

Ideally this print will take you far away, 2016, etching, 60 x 45cm. Courtesy of the artist and Lisson Gallery, London and New York.