When I began pondering the role of sexuality and sensuality in Monster Chetwynd’s works, I was not entirely convinced this line of thought would provide insight into her practice. Of course, I could remember Monster almost naked, painted red with fake papier mâché breasts during the evening of the performances I orga-nised in 2017 in London. Apart from this, I could only think of humour, irreverence, theatricality, do-it-yourself aesthetics, Dada, Brecht and empowering her audience. Not really sexuality.

I thought of her way of working in groups, I thought of her collaborators – many of them are artists working directly with sexual content, which made me start drawing a parallel to Carolee Schneemann’s practice. Then, I started to reflect on the materiality in Monster’s installations, the props and costumes, highly sensual, and specific works in which sexuality became more apparent. I remembered some early performances and the wallpapers in an exhibition titled La Femme de trente ans at Art : Concept in Paris in 2015. The visceral play and use of sexuality, its image and energy, became much more evident to me. Conceiving her recent works as more political, the two giant leopard slugs slimed over my mind – proudly standing around the main entrance of Tate Britain, I see how their nocturnal mating inspired Monster.

Monster Chetwynd, The Supreme Deluxe Essential Monster Chetwynd Handbook, Edition Patrick Frey, Zürich, 2019

Vincent Honoré: How did your study of anthropology influence your work, especially your relationship with eroticism and sensuality?

Monster Chetwynd: It’s hard to know if it only comes from studying anthropology because it might also come from my open-minded parents. In anthropology, on the one hand, it’s a bit negative because you’re not meant to have your own world view. That is, you can have your world view, but you can’t ever seem to escape it. So, when you’re studying other peoples, you’re always meant to be coming from some sort of bias. There is this attempt in anthropology to have an objective eye. I guess you could study different cultures that could seem to be sort of provocative subject matter. Because you’re an anthropologist, you have this sort of scientific cultural studies hat on. You can study that kind of material, but in no way treat it as provocative or sensual, or out there. In a way, anthropology does give you permission to look into and research taboo subjects in our culture. I can see that perhaps through studying anthropology I’ve been allowed or encouraged to research certain subjects that are basically extremely provocative but to bring a different kind of attitude to that research. Not only are you allowed to, but you also potentially pick that subject matter to pieces and not really see it as so sensational that you can’t analyse it.

…Covertly, and mildly provocative. I would say yes, no problem…

Vincent: Do you think your work is provocative?

Monster: I think that my work is mildly provocative, and also not overtly, but covertly political. Covertly, and mildly provocative. I would say yes, no problem.

Vincent: Provocative in its content or in its structure or both? Because it empowers people and it’s a work of collaboration. The audience becomes part of the performance; they cannot solely stand as viewers, they have to become actors.

Monster: Probably both, I’d say both. And also, I try to do the impossible by allowing for – not exactly the world to stop and everyone could get off – but like an unaccountable space. That’s claiming autonomy, which is quite shocking, I guess.

The Panther Ejaculates, 2017, performance at Art Basel. Courtesy: Sadie Coles HQ, London

Vincent: Does it come as well from the parties, the happenings that you were organising in the early 2000s?

Monster: Definitely by experimenting and throwing parties in nightclubs or on the street and even in art communities, like, you know, official platforms as well. I think it also comes from reading a lot of, how do you put it, culture.

I would say a lot of my ideas come from quite provocative texts. Whether it’s from Rabelais and his world, or whether it’s from reading the Futurist Cookbook or various provocative, kind of famous, insightful texts that I have then been excited by. Maybe I’ve come across something while studying anthropology or through art education, but then what I’ve done is quite literally experiment with the ideas in the real world.

Vincent: In your work, the body exists of course, and it’s very much working around the body, the grotesque body, and maybe the absurd body, with swallowing, faeces or organs, bellies, etc. In terms of the erotic content, it’s not that obvious. You have a few works with some erotic content…

Monster: With erotic content, I’ve taken on various subjects when doing certain performances. For example, in 2004 I made a performance called Erotics + Beastiality. It was part of the Liverpool Biennial and New Contemporaries at the time. Within that, I researched the sex life of Nero, Hokusai’s print Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife (1814), where an octopus is making love to a woman and I also looked at Meat Loaf’s Bat Out of Hell, and some poodles that were weirdly, oddly, jumping through a hoop. Whenever I’ve looked at potentially problematic historical information, I’ve also quite bizarrely juxtaposed it with something that’s more playful or not just about that kind of lifting the lid on what it was like to be a slave having sex with Nero. I think I go in by grabbing the bull by its horns, or resolutely headstrong – sort of directly into a subject. When it’s sexuality and erotics, it’s more that I find some historical description. I think it was because I was reading The Lives of the Twelve Caesars by Suetonius, and these incredible descriptions of sexuality in the Roman Empire, which I was really interested in. I found it extremely – it sounds so intense what I’m going to say – but I found it so interesting that Nero would allow himself to be penetrated, which was not seen as culturally acceptable. Men penetrating other men was acceptable, but to be the one who was penetrated was completely taboo. And he was an emperor and practising this. He was, in the same way, practising being an artist, which was also taboo. So I was interested in the fact that Nero is so completely famously historically written off as a really bad person. If you read the biographies about him you come across innovative, brave things that he experimented with. But this is not given any credit because of the other bad things he did.

I was just very engaged with the idea of some of the inventiveness, of sexuality that doesn’t seem to be current anymore. For example, I used to love Eurotrash, which was a TV programme presented by Jean-Paul Gaultier. I just adored it so much. It’s as if a lot of the celebratory sort of ludicrousness of sexuality isn’t really as common. That it’s suppressed in the same way as humour. I’m, not exactly proud, but I would happily lift the lid off those kinds of subjects. To look at them and, in a playful way – in a nightclub, a house, in the street, in the domestic, some space that’s allowed to – experiment, where everyone’s volunteering to do it. If you’re a group of colleagues, obviously we’re all consenting adults. There’s a level at which it is obvious that more people would be interested in it, too. Because if ten people are interested in looking at these ideas, then a group of a hundred people would be. It’s seeing that it’s something that could be worth discussing.

Vincent: Interesting that you compared sexuality with humour. Your work is a lot…

Monster: Yes, as suppressed, equally suppressed, yes.

Vincent: As a sort of a celebration of life, of freedom, of reinventing yourself.

Monster: Yes, for example, I don’t want to make you laugh so much, but I always talk about ‘dogging’ in British culture. Hopefully, everyone knows what dogging is. It’s basically when people used to – and I’m sure they still probably do – go to car parks and have sex in groups. It was basically sort of spontaneous in that you would sort of go out and find it. Why I found dogging so exciting, and odd, and interesting, is because it’s to do with a not prescribed lifestyle. It’s like someone reinventing and doing something entirely for themselves. In a weird way, that’s quite radical. It’s great that people do these kinds of things. Hilarious.

Vincent: You did this with this work called Hermitos Children from 2008.

Monster: Yeah, I love that piece of work. I made a film scene set on boats and pretended it was by people, mainly women, who had sex and it was called ‘catting.’ There’s the dildo see-saw, which is brilliant, in my opinion. I thought it was funny when you initially asked me about ‘sensuality’ in relation to my work. The sexuality that I’ve researched is a more conscious provocation to see what you can get away with. Sensuality is different, it’s very intimate. Sensuality is kind of like a piece of contemporary dance that was linked to the touch of skin, you know what I mean? I was listening to you, thinking ‘oh my god, like what do I have to do with sensuality?’ I must have been in denial, you know when you first asked me, I was like, what? Uhm, maybe?

Marvin Gaye Chetwynd, Hermitos Children, 2008, video still. Courtesy of the artist and Studio Voltaire, London

Vincent: I think you were in a very particular British denial about sex and sexuality.

Monster: When it comes to using the idea of sexual expression and how it’s suppressed, Hermitos Children was provoked in my mind and inspired by this really good documentary called This Film Is Not Yet Rated (2006) by Kirby Dick. It’s basically about an American man who researches why certain films that show female sexuality are immediately given an X-rating, rather than films that have a more mainstream appeal, like American Pie, that depict overt sexual behaviour with boys. As soon as it’s a girl reaching to her lower parts, that’s given an

X-rating. He interviews super interesting directors like Kimberley Peirce who made Boys Don’t Cry (1999) and John Waters, who explain the really terrible situation in American culture. Basically, these censors parade around as if they were officially government-enforced, but of course, it’s not. Censorship is all done privately. There is a brilliant scene where it’s split-screen, on one side female sexuality, not very provocative, and on the other, male sexuality. On top, it shows which rating each got. And it’s unbelievable, the amount of the female sexuality that’s squashed. So then I thought, ‘Oh, I’m going to make an outrageously sexy female film and see what happens.’ And instead of being squashed, it was put on display by Nicholas Burrough in Altermodern: Tate Triennial 2009 at Tate Britain, which ended up buying it. My experiment was to see what could you get away with and whether it be welcomed by Western culture as a form of expression. The answer was a massive ‘yes.’

Vincent: And that was a film, not a performance?

Monster: That was the Hermitos Children, the pilot episode. As for sexy performances, one of the most outrageous was in 2004. In Erotics + Beastiality we were in Liverpool in this warehouse. A very sexy female figure was making love with a massive puppet of an octopus. Someone, almost like a Roman soldier with an enormous willy, like a willy as big as a person, was going round and various people were excited about that. That was pretty outrageous. Within the Hermitos Children, there’s loads of really overtly sexual stuff, loads of dildos. It’s called ‘the case of the poisoned dildo.’ There was a lot of dildo action in that film. And then, the dildo see-saw is amazing.

Vincent: Tell me about that!

Monster: I came up with this really stupid idea of putting a dildo on each end of the see-saw, and pretending that the figures sit on the dildos and then ride the see-saw. And then, the joke of it, which is like the more sophisticated part, is that I took the script from The Red Shoes (1948) by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. It’s a technicolour eat your heart out, escapist film made around the end of the Second World War. A really sumptuous and theatrical watching-experience, with a wonderful fairytale or story about this girl who puts on these red shoes and dances herself to death. It’s a tell-tale, moral story where you’re meant to learn to be careful about the obsession of creativity. It’s brilliantly done in the film. I took the script from that and instead of the red shoes, I made it the dildo see-saw. The girl, hilariously, wants to be a sex dancer, and ends up becoming obsessed with being the best sex dancer ever. She does this thing of riding the dildo see-saw and the audience doesn’t ever let her stop. She ends up feverishly dying on the dildo see-saw. We filmed it all, of course, and it was hilarious.

Toxic Pillows. Photo: Maarten Nauw. Courtesy: De Pont Museum, Tilburg and Sadie Coles HQ, London

Vincent: Tell us about the wallpapers that you created with the naked figures.

Monster: Then I did a show in 2015 in Art : Concept, one of the good commercial galleries in Paris. I mixed some Neolithic carvings of very voluptuous female figures with photographs of slightly handsome men, and sensual photographs of people with odd shapes like natural pearls. You know how natural pearls look sometimes like penises. I was just collaging things and being playful. Some of the images are very provocative, not overtly pornographic. You couldn’t say they were porn, but something about the way they’re placed and cut makes it quite shocking. I love them a lot. I printed them really big, 4 metres by 3 metres, the size of a wall. I was invited to do it, but when they arrived in the gallery I remember they caused a stir. People did not know how to quite cope with them because they were too sexual, too intense.

Afterwards, in Liverpool, the Walker Art Gallery had a really interesting young curator called Charlotte Keenan. She was putting on a show where she reimagined the history of display in museums, particularly looking at sexuality. For example, Greek sculptures that hadn’t been showcased before because they are somehow ‘wrong’ in art today. For example, there’s this very famous marble statue of a satyr who’s having sex with goats and everyone’s a bit like ‘oh my god,’ like, ‘what is that?!’ Two of my sexy collages were put on display and they looked really amazing. The gallery had good discussions in the space, where contemporary theorists and members of the public could come into the show, and talk about queer politics and contemporary sexuality. I think that show, in a weird way, was very successful. It was really nice that those collages had that journey and the collection bought them, not as if they’re not respectable or too provocative. There seems to be some level where they’re being collected by museums.

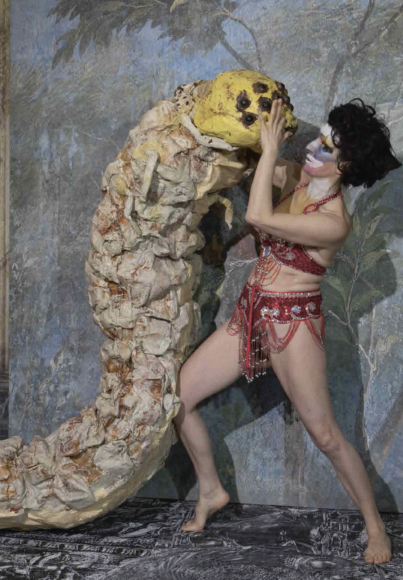

In 2016 at the CCA Galleries Glasgow, I was invited to do an exhibition. I made an installation where I printed huge – again, 4 or 5 metres high by 6 metres long – stretches of Japanese prints called Shunga because I’ve had this long journey of research and connection with the Hokusai print. I made a sort of performance, an event, where I was naked and painted red with jam all over me, which was a mistake. It was extremely sticky and disgusting. But I was held upside down in a really great pose, I think it was from opera. That’s where four people hold you up, upside down. Then I spoke from a microphone. It was incredibly provocative, both visually and physically. I tried to make a film about the same series, which is Hermitos Children, but moving on in the story. The protagonist is a telepathic sex detective. I was really keen to link myself – although who knows if I’m allowed because of all sorts of other issues like cultural appropriation, but I feel that I’m allowed – to the history of Shunga art when pornography, or supposedly sexual images, were not seen to be smutty or low culture. Instead, Shunga was actually accessible to all ages – women, men, everyone. It’s a very strange thing, but these works became dear to people. They were not marginalised and thought of badly. It was the opposite. Everyone would enjoy this form of pornography or this form of sexual, erotic art. They were thought to keep you safe from fire. Newlyweds would be given these books of sexy drawings. Oddly, the idea was that not only would they help lead to a healthy marriage and a happy life, because you’re embracing this love to sexy images, but that you are somehow safe from domestic fire. People even took these images into battle, they had all sorts of associations, and always good. In Rabelais and His World, Michail Bakhtin talks about how he doesn’t understand why culture always ‘forces down.’ Sexuality and humour are considered to be base, reductive somehow. But Shunga art from mid-1700s Japan really operates in opposition to this hypothesis. It was allowed, it was there. Everyone was okay with it.

Marvin Gaye Chetwynd, An Evening with Jabba the Hutt, 2003, performance.

Vincent: That’s incredible. It’s a very good story.

Monster: It’s like Frank Zappa was president, isn’t it? Which nearly hap-pened in the Czech Republic, didn’t it?

Vincent: Is sexuality still a theme or motif you want to explore in your work? Is it something you have in mind?

Monster: Such a good question. I’m thinking again about the difference between ‘sensuality’ and ‘sexuality’… I remember going to this brilliant club in London called Stunners. It was a very niche sex club that had parties from 3 to 5 am. You felt very liberated and free there. Not because you were having sex, but actually because you could tell that everyone in the room was not judgemental. It was so strange to have that experience. I was waiting by the bar to get a drink, and a woman crossed the room, came straight up to me, and started talking to me about Evelyn Waugh and evil in war novels. I don’t know how to say it, it was nothing that you could… it was unpredictable. And it was totally relaxing. Another man came up to me and asked me if I wanted to have sex with him, and I just said no, and he walked away. It was as if a lot of the stress and problematics and classic kind of nightmarishness of courtship went out the window in some way. It was quite hilarious. Interestingly I didn’t have sex, and I didn’t feel voyeuristic either. I just felt really relaxed and at home. What I did feel after is I think my

sexuality is linked to more romantic entanglement, which is why I wasn’t that turned on. If I was to think about work now, with sex as subject matter, for some reason it’s not on my agenda. What’s happening in the next projects are sort of more to do with the history of electricity, or green politics.

So, not at the moment.

Vincent: Not at the moment, but maybe, who knows. After this conversation and now recalling the sexual inspiration within your works. After all these years of denial, you look back at something special…