Alasdair Gray is the best novelist you’ve never read. His appeal? Surely the extent to which he lays his own soul bare which is both compelling in its ruthless honesty, and moving in its humor and humanity. Eroticism, sexual impulse, pornography, and sadomasochism are key to his unflinching vision. The picture he paints of the human soul is at once terrifying and inspirational, endearing and repugnant. The novels always manage to be entirely original whilst simultaneously ventriloquizing writers and artists from throughout history in a baroque collective conversation between all texts that have been and that will ever be.

I first came across Alasdair Gray’s writing when I was given Poor Things. I was soon devouring the 800-page tome that is his most celebrated novel: Lanark. Like the great modernists before him, most particularly James Joyce, Gray set out in this book to tell the story of a life, and perhaps of a nation, or the entire history of literature, from infancy to death, and surreally, back again. His great departure was to stir the pot of this form; in Lanark’s pages gritty realism gives way to fantasy and science fiction. The ordering of the novel is as bloody-minded as the author himself. We start with Book 3, then the Prologue, Book 1, the Interlude, Book 2, and finally Book 4 ends the story but is interrupted by the Epilogue. It is in this Epilogue, an extraordinary moment in which the protagonist speaks to the writer himself, that Gray lays out his art:

‘Your survival as a character and mine as an author depend on us seducing a living soul into our printed world and trapping it here long enough to steal the imaginative energy that gives us life. To cast a spell over this stranger I am doing the most abominable things. I am prostituting my most sacred memories into the commonest possible words and sentences. When I need more sentences or ideas I steal them from other writers, usually twisting them to blend with my own.’

This deft self-reflexivity, shift in tone, encyclopedic knowledge of literary history, and above all sense of humor, is what endears Gray’s fiction to me again and again. In the case of Lanark it was well ahead of its time. Gray was repeatedly advised by his publisher that the form was problematic and that the book was best cut in two, realist novel and sci-fi trash sensibly divided. Gray thankfully prevailed.

The novel ends with a ‘Tailpiece: How Lanark Grew’ in the form of a Q&A in which Gray sets out the responses he would make to anyone’s questions regarding Lanark – perhaps a hint at his approach to anyone attempting to interview him thereafter. What follows is an attempt at a conversation with the writer through the poor medium of email. My annotations and footnotes expand and contract a refused exchange in a style that this slippery, devilish, talented postmodernist would hopefully appreciate.

Natasha Hoare: You’ve previously described yourself, as the author featured in the Epilogue of Lanark, as a ‘deranged and rather unstable creature.’ Does this hold true?

Alasdair Gray: Yes.

Natasha: You are currently working on a Herculean translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy; how far has this text influenced your own writing?

Alasdair: I do not call my version of Dante’s Comedy a translation but a paraphrase; I do not know Italian, so have based it on several English translations. I finished it last week. Since starting it in October 2012 my only other writing has been political articles. I do not think it has influenced them.1

1. Despite Gray’s assertions otherwise, Dante’s Divine Comedy, and its descriptions of the many circles of Hell, are an apt comparison to Gray’s novel Lanark, a Scottish reworking of Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, in which a protagonist moves further and further into a dystopian world, whose demonic internal logic owes much to Joseph Heller’s Catch 22.

Lanark is an astounding feat of autobiography, science fiction, fantasy and realism which was written over a period of about thirty years. The novel traces the story of Duncan Thaw – a stand-in for Gray himself – from infancy spent in tenements in Riddrie to adulthood begun at Glasgow School of Art. Duncan, who is by turns pathetic and mock-heroic, becomes further and further mired in his own fantasies and hallucinations, his body prone to attacks of asthma and eczema. These worsen with the deepening of his twin obsessions, art and sex, until he commits a fevered murder and throws himself into the water to drown. His story defies death, continuing a displaced dimension, still somehow Glasgow but now called Unthank, a dystopian city existing in a permanent state of darkness. Now named Lanark, his skin condition is called ‘dragonhide,’ a disease that eats up the subject entirely until one explodes with ferocious energy, which is then harnessed by an underground institute, which uses it for power. Other patients are pulverized to make food for its inhabitants.

Natasha: Do you prefer reading stories about sinners or saints?

Alasdair: I don’t define people in that either/or way.

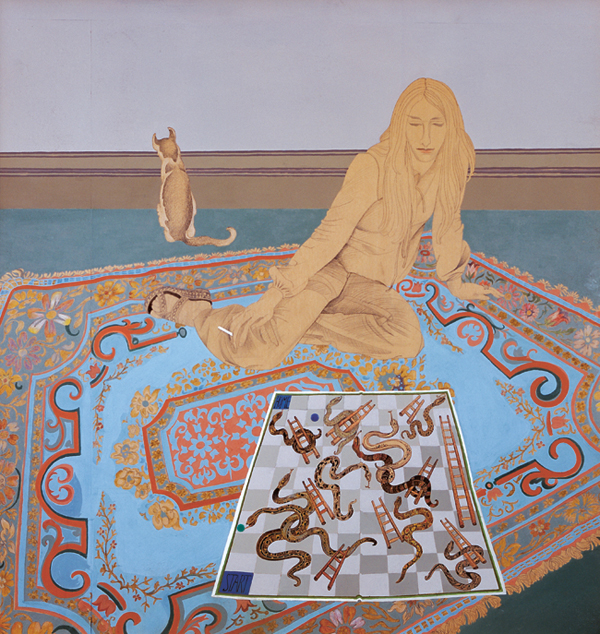

Snakes and Ladders (film sequence with Liz Lochhead) 1972

Courtesy: Alasdair Gray and Canongate Books

Natasha: There is a rich intertextuality in your work – Franz Kafka, James Joyce, Mary Shelley to name a few. Which contemporary writers do you draw inspiration from?2

Alasdair: I don’t remember drawing inspiration recently.3

2. In the Epilogue of Lanark Gray lists all the writers that have informed the novel. The list goes on for over ten pages.

3. I suspect I am the victim of a typical Gray pun here. However far he denies the influence of contemporary writers, his own influence is widely felt. His work has been received with critical acclaim within Britain, and most especially his native Scotland, with fans from both the literary world: Kathy Acker, Will Self and the visual arts; Douglas Gordon and curator Hans Ulrich Obrist amongst many others.

Indeed the latter first en-countered Gray when visiting Glasgow in the early 1990s, when the art scene there had found an incredible lease of life: ‘so many artists were reading his books, so I read the extraordinary Lanark then many more books, also the poems, and the plays. There are many dimensions to Alasdair Gray’s work and also his visual work – the drawings, portraits and paintings – he is a very holistic artist.’ This flowering of culture in Scotland in the 1980s and 1990s, sometimes called the Scottish Renaissance, is in no small part due to the art and literature of Gray, and his peers John Kelman, Liz Lochhead, and Tom Leonard, amongst others.

Natasha: Sex and the erotic swirl constantly through your narratives; why the primacy of these drives?

Alasdair: Ask any Freudian analyst.

Natasha: What is the difference between eroticism and pornography?

Alasdair: I cannot give you a better definition than you will find in a respectable dictionary.

Natasha: Do you think literary and visual eroticism runs deep in your native Scotland, despite the legacy of Calvinism?

Alasdair: No nation could exist without the sex drive, also widely known as love. It is as basic as the wish to avoid death, which fades as love fades.

Natasha: Can eroticism be political?

Alasdair: I have written novels on that assumption.4

4. Sensuality and sexuality looms large in Gray’s work, and is at once part of his very particular form of truth-telling, and a metaphorical mediation of his socialist politics: a way to shock us out of passive reading, and into active engagement. Perhaps his boldest work in this vein is the novel 1982, Janine (1984). In it the central protagonist, Jock McLeish, a mediocre supervisor of the installation of alarms, hits rock bottom in a hotel room in Greenock – an insalubrious area of Glasgow. Divorced, fifty years old and alcoholic, McLeish spends the night vividly creating his own personal pornography through an incessant and powerful stream of consciousness, featuring various women in sadomasochistic roles: from Janine herself, who is a Jane Russell type, to Big Momma, an obese lesbian. Gray himself described the book thus: ‘This already dated novel is set inside the head of an ageing, divorced, alcoholic, insomniac… Though full of depressing memories and propaganda for the Conservative Party it is mainly a sadomasochistic fetishistic fan-tasy. Even the arrival of God in the later chapters fails to elevate the tone. Every stylistic excess and moral defect which critics conspired to ignore in the author’s first books, Lanark and Unlikely Stories, Mostly, is to be found here in concentrated form.’

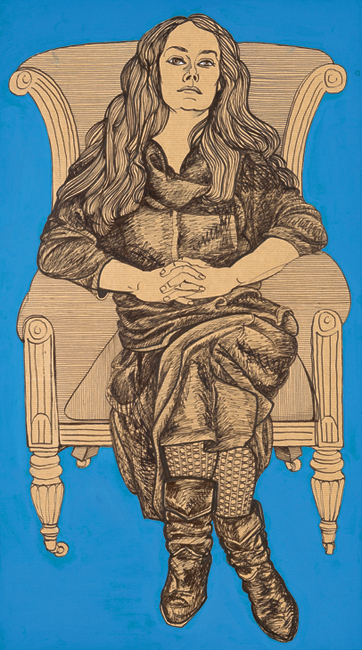

May in Black Dress on Armchair 1984–2010

Natasha: Legend has it that Kathy Acker encouraged you to write with a female protagonist and thus you wrote Something Leather? Is there a synergy between her work and your own?

Alasdair: At an interview in London Kathy Acker asked why I had never written fiction from a woman’s point of view. I said I did not know women enough to do so. Her question may have prompted me to attempt it in Something Leather. I am not sure what synergy is. About twenty years ago I read and liked two of her books.

Natasha: In an interview with Acker you point to James Joyce when he says that ‘proper’ art should not move, that only improper arts such as propaganda and pornography move us.5 Do you intend to move people by writing pornographically, and if so are you uninterested in ‘proper art’?

Alasdair: In 1982, Janine and Something Leather I intended to move readers pornographically in order to overcome that with a Socialist message that I wished them to emotionally deduce, rather than spelling it out for them.

5. ‘The feelings excited by improper art are kinetic, desire or loathing. Desire urges us to possess, to go to something; loathing urges us to abandon, to go from something. These are kinetic emotions. The arts which excite them, pornographical or didactic, are therefore improper arts. The esthetic emotion [of proper art] is therefore static. The mind is arrested and raised above desire and loathing.’ Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man.

Natasha: Both Something Leather and 1982, Janine are full of sadomasochistic fantasy; you’ve stated previously that you can’t reread the latter, despite it being one of your best books. How did it feel to release this intensely personal vision to the public?

Alasdair: Pleasant.

Natasha: Jock McLeish, the novel’s protagonist, is a normal man consumed by his own fantasies to the point of nervous breakdown – do you think that the onerism of sexual fantasy is the path to total solipsism and eventually insanity? Is this a metaphor for the process of writing itself?

Alasdair: Obsessive fantasies of any kind make people lonelier, but I think most obsessives don’t go clinically insane.6

6. Note the avoidance of the writing metaphor.

Natasha: How far have attitudes to eroticism changed since the publication of Janine in 1984? Do you think it would have a different reception now?

Alasdair: To the first half of your question: attitudes have changed a lot; to the second half: yes, there would be less fuss about it.7

7. 1982, Janine’s publication was the cause of much critical consternation due to its pornographic content and perhaps remains one of Gray’s least understood works. In an interview with writer Kathy Acker, Gray quotes James Joyce: ‘…“proper” art should not move, that only improper arts such as propaganda and pornography move us.’ In 1982, Janine, then, and later in Something Leather, he explored this rupture between proper and improper, harnessing the power of the pornographic register intending ‘to move readers pornographically in order to overcome that with a Socialist message, which I wished them to emotionally deduce, rather than spelling it out for them.’ In matching Conservative Party dictums with the visceral and disturbing power of the female characters – who although being sexually fantastical creations have very real voices that rend and tear at McLeish to the point of his attempted, but failed, suicide – Gray pairs politics with pornography in a way that is performed daily by British tabloid newspapers, and reveals much about the right-wing politics of the day.

Natasha: In your art work and writing, women’s bodies are particularly malleable, both under the projected fantasies of your male protagonists – here I think of Janine – and Bella under the supposed surgical skill of Godwin Baxter. As the maker of ‘imagined objects’ which women have been your favorite creations?

Alasdair: Bella.8

8. The novel Poor Things, of which Bella is the star, was my first encounter with Gray. An homage to Victorian Gothic fiction by way of a reworking of Frankenstein, with sex, madness, and unreliable nar-rators at its core, it appealed immediately. The book is a contorted version of the Mary Shelley classic. Wrapped as hers is in epistolary form, each narrator undercutting the other, the story becomes more and more fantastical, until Gray himself makes an appearance to describe his friends’ discovery of these very manuscripts. Who is telling the truth? Who is a complete fantasist? Who is the author? Like an ornate Russian babushka Gray led me from Scottish grave robber, to Parisian bordellos, suffragettes to the cruelty of English colonialism, all the while dancing with literary genres, form, and image – for it is here as well that Gray leaves his indelible mark as an artist. Each of his novels is wrought with illustrations in his inimitable black line. Like the William Blake of Glasgow, a political firebrand as well as a sensualist, in love with the human form, especially dark-eyed women, and an acute observer of his native Scotland.

Natasha: Whom do you base your drawings on?

Alasdair: Portraits are made by looking at people in front of me. Invented illustrations use portraits of folk I know whenever possible but other stuff too.9

9. Gray’s virtuoso intermixing of literary forms, canonical texts, and popular culture renders his achievement as being against all literary fashions or trends. As such, and as he advises his own protagonist, the writer and artist Duncan Thaw in Lanark, ‘I’m afraid you are going to pay the penalty of being outside the main streams of development.’ His visual art equally lies outside of categorization, a linear illustrative style that speaks volumes of his love of William Blake, another firebrand visionary.

Natasha: To read your novels is to engage in a sensual process in and of itself – with image and typography used evocatively. Is your intention to entertain above all?

Alasdair: I write and draw to entertain myself, assuming that if I can do that I will entertain others.10

10. I, for one, am wholly enter-tained.