Some people just have a vibe. Argentine filmmaker Lisandro Alonso is one of those people. This was immediately clear to me when I met him at a documentary festival in Copenhagen in 2013. He was there to give a masterclass, despite his not being a documentary filmmaker. Slouching in his chair, looking a bit like a trapped animal, he presented clips from ‘La Libertad’ (2001), ‘Los Muertos’ (2004), and ‘Liverpool’ (2008) – the aptly named Lonely Men Trilogy that established Alonso as the decade’s auteur of ‘slow cinema.’ Like his taciturn protagonists, Alonso gave the impression that he would be fine living dialogue-free, at least around film journalists. But despite this distrust of words, he exuded palpable warmth – something that’s confirmed when you spend any time with Alonso one on one. It’s hard not to be seduced by his vibe. He’s watchful and sensitive, much like his films. They are intensely attuned to bodies, gesture, and the rituals of daily life, which makes them erotic, even if the subject matter is not. His camera feels both generous and unflinching. Even when depicting violence, the effect is not cold, but sensuous and mysteriously human.

Maybe that’s why Alonso strikes me as someone with whom you could be in the middle of nowhere – not because he’s some kind of survivalist, but because his worldview would put you at ease. He has an unhurried relationship with time and space. When he made La Libertad, he ventured into the Pampas where he found and lived with a young woodcutter named Misael, who eventually became the film’s silent protagonist. In a sense, this is how he’s made all his films: he travels somewhere remote, meets some people, and seduces them into making a film that’s partly about them and partly about him.

So perhaps it should come as no surprise that Alonso eventually charmed Viggo Mortensen, the artist-musician-poet and sometime Hollywood star, to join him on his latest, strangest trip. In Jauja, Mortensen is Captain Gunnar Dinesan, a Danish engineer assigned to a remote army outpost in nineteenth- century Argentina. His beautiful teenage daughter Ingeborg is on the verge of discovering her own sexuality, and her presence arouses desire in the soldiers and disrupts the harmony of the all-male community. When she suddenly disappears with a young soldier, Dinesan pursues her like a spurned lover chasing a hopeless dream.

The film’s title refers to a mythical place forever beyond our reach, and Alonso’s film teases us with possible interpretations. Space and time begin to bend in the film as Dinesan’s search for Ingeborg in the desolate Patagonian desert becomes increasingly desperate. As the twin themes of eroticism and existentialism coil, Jauja mutates from deadpan western into a hypnotic, trance-like odyssey.

The effect is greatly enhanced by Timo Salminen’s lush color photography, and the use of the classic 4:3 ratio, which makes the images feel outside of time. Mortensen, who also produced the film and co-wrote the minimal score, is the film’s emotional anchor.

As Ingeborg’s sexuality blooms, Dinesan must grapple with his own loss of innocence.

Paul Dallas: Your early films document real people in fictional circumstances, but they still managed to feel dreamlike. Jauja is a dramatic departure for you. For one thing, it’s a period piece with costumes. But it’s also the most literary film you’ve made.

Lisandro Alonso: In general, I tend to focus on reality and to film the things that I see around me. But with Jauja, I consciously tried to move away from reality, and to enter into some kind of imagined micro world. I got in touch with the poet and novelist Fabián Casas, who became the film’s co-writer. He’s the one with the vocabulary and imagination. He’s able to connect parallel worlds and dreams, poetry and reality all together in a way that creates a new kind of structure. This is what makes Jauja so different from my previous films.

Paul: Jauja seems to be about the end of the rational world. Captain Dinesan is a colonial European living in a place where the rules of ‘civilization’ no longer apply. This also happens for the viewer, in a sense. The film is not linear: the time period changes abruptly and characters seem to disappear and re-emerge at will.

Lisandro: Yes. I wanted to create connections across space and time. My films ask the viewer to use their imagination. After a while, they start to get into the mood. Maybe they ask, ‘What the fuck am I watching?’ Or, if they’re more open, the film starts to feel unreal. It takes time to think about what’s really happening. Maybe it doesn’t transport you somewhere else, but puts you on a different level of reality. It can be a bit like a dream, even if the film is based on real things. Hopefully, there is a moment in the film where you start to fly, you know?

Jauja

Viilbjørk Malling Agger & Esteban Bigliardi Courtesy film stills: Lisandro Alonso

Jauja (2014) is set – according to Alonso’s notes, although the film never states this – in Patagonia in 1882, and all we know from what we see on screen is that a small detachment of Argentinian soldiers is posted on a remote stretch of coast inhabited mainly by loudly roaring seals. Posted with them is Danish captain Gunnar Dinesen (Viggo Mortensen), accompanied by his teenaged daughter Ingeborg (Viilbjørk Malling Agger). The company’s boorish lieutenant, Pittalunga (Adrian Fondari), first seen bare-chested and masturbating in a rock pool, has designs on Ingeborg, but she elopes with a young soldier. Dinesen rides off into the wilderness after Ingeborg and her lover, but it’s a dangerous terrain – inhabited by indigenous people whom Pittalunga contemptuously names ‘coconut heads’ and commanded by a renegade officer named Zuluaga, a sort of Kurtz of the Pampas, said to have gone mad, to wear a dress, and to be possessed of superhuman powers. Courtesy Jonathan Romney

Paul: There are hints of sexuality in the film. It starts with the first scene. We see a soldier masturbating in a pool of water. In the distance, is Ingeborg. Immediately, we know that desire will be the force that disrupts the order of the place.

Lisandro: Well, he feels inspired by the girl! [Laughs]. I wanted to show that this is not a normal period film, and that weird things will be happening, like this man masturbating in freezing cold water. For me, it’s about portraying this sort of animal instinct. Even if this soldier’s role is to protect the girl, he also wants to marry her. She is a blond girl in the middle of nowhere. The first thing you think about is sex. Or maybe that’s how I see it. Maybe I’m a bit like that guy. Who knows? It’s crazy to bring a young girl to that land at that time.

Paul: The surprise, of course, is that Ingeborg runs off with another guy. The men are not the only ones who are lustful and want sex.

Lisandro: Yes, you can smell it. She simply chooses a different guy. Viggo’s character is the only one who doesn’t realize what’s going on. She’s young and living in a fantasyland. She wants to run away, even if it’s dangerous. The person who really influenced how I conceptualized Ingeborg was the ’70s British fashion photographer David Hamilton. He’s known for this other body of work in which he photographed underage girls that are more or less naked. He’s a weird guy, and the photos have this naïve quality. I don’t know if I like the work. [Laughs]. You can’t tell if you can trust this guy. The girls in his pictures are starting to feel like women. They’re aware of their sexuality, and I think this informed how I thought of Ingeborg. She even looks a bit like one of those girls.

Paul: The way you photograph the sex scene between Ingeborg and the young man is intriguing. Instead of seeing the two of them naked, the camera shifts, and we’re looking up through the grass into sky, from her point of view. Was this about discretion, and looking away?

Lisandro: Yes, I was afraid. I thought about whether or not to show them naked. This was the first time Viilbjørk Malling Agger, who plays Ingeborg, was acting in a film. She’s young and her mother was there during the shoot. I don’t think she was prepared to be naked, and I’m not sure I was prepared to shoot that. We talked about it and decided to shoot it this way. I just couldn’t shoot the scene with them naked. Maybe it’s something I’ll attempt in my next film.

Dinesan is in shock when he realizes that he’s not going to see his daughter again. He’s suffering and alone and far away from everything that he knows. My interpretation is that the film tries to get into his head to understand what he’s feeling.

Paul: Even though Jauja is very much concerned with bodies and landscapes, it seems to be evoking a space that’s more connected to the subconscious.

Lisandro: That’s what we tried to do. Dinesan is in shock when he realizes that he’s not going to see his daughter again. He’s suffering and alone and far away from everything that he knows. My interpretation is that the film tries to get into his head to understand what he’s feeling. The moment when he sees the dog, after he’s lost his daughter, everything starts to get twisted. The film is shifting and, as a viewer, you try to understand that change. But at some point, it’s no longer about understanding. It’s about something else. Viggo often says the film is just the dream of the dog. Of course, he’s just trying to escape from any answer. I agree that it’s difficult to define. I finished the film a year ago, and I am still unable to analyze what we created. I guess the film is a bit dreamy.

Paul: In a sense, it’s about creating a space that’s beyond language. It’s about feeling and sensation. But I find it interesting that all of your films take place in remote places and feature landscapes so prominently.

Lisandro: I grew up in the suburbs of Buenos Aires, but I was always in touch with the countryside. When I was growing up, my father took me to a farm two hours outside the city. It’s where I spent most weekends. This experience of playing in nature and being close to animals and the dirt left a huge impression on me. It’s very different to play outside in nature, away from city life. Even now, I remember those two days a week I spent at the farm much better than the five days a week I spent at school.

Paul: When you made your first film, La Libertad, you actually lived out in the wild with Misael Saavedra, the young woodcutter. He had never acted before, but became the star of the film. You were both in your early twenties at the time.

Lisandro: Yes, this was an eight-hour drive from Buenos Aires. When I saw this guy, living out alone in the forest, I just felt a kinship. This was fifteen years ago now. I identified with Misael, even though I was from a city of ten million people. We were both young and somehow we were very similar despite our backgrounds. We didn’t like communicating much with other people. We were completely isolated.

Paul: Do you feel differently now?

Lisandro: Before La Libertad, it was as if I was walking without direction. Now I have a family and a home, so I must feel some other way. But it’s also because through meeting Misael and being in the forest – through making this connection and making the film – that I began thinking in a different way. It made me feel less alone somehow. When the film was accepted at festivals, and I started traveling, it was an entirely new experience. I was meeting people because of the film, and I discovered the possibility of being part of a community. I see filmmaking mainly as an excuse to be with people.

Paul: It’s something that’s true for all of your films. They all emerge from deep connections you make with different people – whether it’s a non-professional actor like Misael or a Hollywood star like Viggo Mortensen.

Lisandro: That’s right. I like to be with people who make me curious. Maybe I admire them or just want to spend time with them. In the case of Viggo, I first saw him on screen in the movies. But then I started reading about his connection to Argentina and what he does for art – poetry, painting, music – and I got in touch through a mutual friend. To me, Viggo is unbelievable. It’s more than him simply being a well-known or charismatic actor. It’s because of him that the actors in Jauja speak in Danish. Because of his involvement in the film, we were able to film in Denmark. I think it made the film much better to have this element.

Paul: This strong desire to be elsewhere, to be far away with people very different from you, is very powerful.

Lisandro: Like everybody else I like to travel and discover new places. But I don’t use the people I meet as a mirror to myself, or the things that scare me. We all just feel alone as they do. I feel this with La Libertad, Los Muertos, and Liverpool. Maybe we come together to make a film, but at the end of the day we are probably going to stay alone. For my next film, I’m trying to go to the Amazon in Brazil. The population there is still eighty percent Indian. I’m curious to see how they live, even if I can’t speak their language. I have no rational explanation why, but I know I want to go to these places. I look for new adventures.

Paul: This existential current you mention is an underlying theme in all of your films.

Lisandro: Even if you are connected to others or have a family, you will probably feel alone in the last days. We are alone in every decision we make every day. But as for feeling alone as a human being, it probably has to happen at the end of the day. The people I like to make films about live like that all the time. They don’t know what it’s like to be comfortable, or protected in a city by laws. They refuse these conventions, so they just go off on their own. Misael and Argentino, the actor from Los Muertos, are both like that. The city and cinema are both foreign to them. That’s in part why I made Fantasma (2006). I brought them both to Buenos Aires and filmed them wandering through the empty Cinemateque. They wind up watching the movies that they acted in.

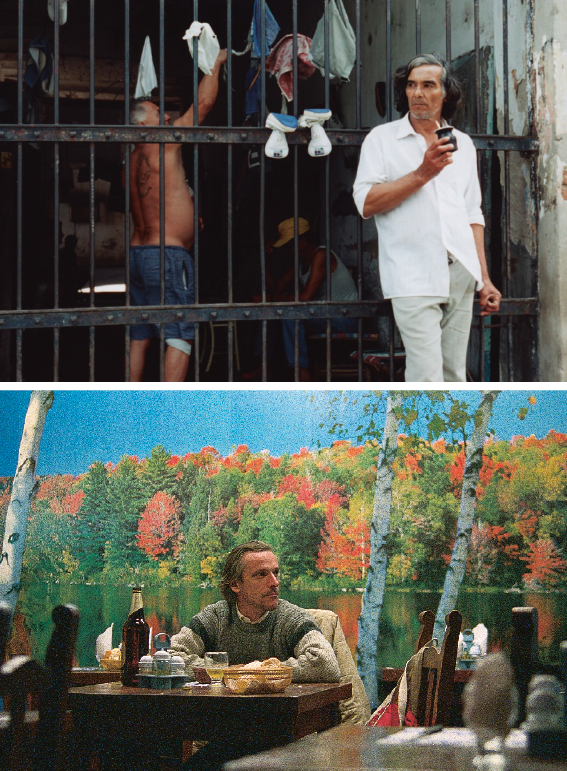

Los Muertos

Minimalist masterpiece about a grey-haired ex-con who returns through the jungle to his family. The emptiness is sublime in Los Muertos (2004), the second feature by Lisandro Alonso. In the opening scene, the camera’s eye glides through an antediluvian jungle. Between the leaves, we catch sight of two dead boys and their murderer. Then the film takes a leap many years forward in time to the intriguing old man Vargas. His last day in jail has dawned and he is getting ready to taste freedom again. For the rest of the story, Vargas is on his way to his daughter who lives on an island in the jungle. A meditative boat trip in a tempo determined by the primary necessities for life. Vargas is trimmed by a barber, visits a whore and slaughters a wild goat on the way. In silence, he is one with the jungle and the river that takes him both forward and back in time. Apart from that, there is nothing but silence, the gruesome secret that Vargas bears with him and the viewer’s nagging questions. Courtesy IFFR

Paul: It’s significant that Misael appears in Jauja. He’s only in a brief scene, but you give him a crucial role: he plays an Indian who steals Captain Dinesan’s horse. It’s a pivotal moment because the horse represents his connection to Ingeborg. After that, Dinesan has very little hope left. The scene also seems like a commentary on cinema itself. The two actors would never have existed together outside the space of your film.

Lisandro: It was very important to me to have Misael and Viggo in the movie together. I feel very happy about that. When we were shooting the film, Viggo probably felt exactly like his character. He probably wondered, ‘What the hell am I doing out here with these guys?’ But I really appreciate that he’s one of those people who takes real risks. Viggo spent part of his childhood in the countryside of Argentina, so he’s connected to the place. But he has this openness. His Danish passport probably allows him some freedom to live in different places. During the shoot, we were like gypsies in a little caravan. Some nights, I just slept in a tent. It was like that with La Libertad, which was shot close by, about 400 kilometers away. No bathrooms,, no internet, no phones. Just the film, the crew and the landscape. To make this type of film, you have to feel that it’s the only thing that you have. As I’ve been working with the same people since I started, we are like an odd family.

Simple questions are also complex: What do we need to be happy? How do we communicate with each other?

Paul: The Patagonian landscape where Jauja is filmed is desolate and sublime. How did it make you feel to be out there?

Lisandro: Places are like other characters to me. Jauja starts in an isolated but very sunny coast and we end in a lunar cave. You can read in the landscape that everything in the story is getting darker. What I like is to feel connected with a place, to forget about all the conventions of city life – my wallet and my ID, all that stuff. I want to focus only on the people around me. When it comes to the energy of the characters or the feelings I’m after – I don’t know where they come from. It happens like this more or less with most of the films I have directed: I just feel connected with the person and with the landscape. I don’t entirely understand why. Maybe it’s motivated by a more primitive question like, ‘What are we doing here?’ Simple questions are also complex: What do we need to be happy? How do we communicate with each other?

Paul: As you said, Jauja operates on a kind of dream logic. This brings up the question of intentionality and how much is planned versus how much is improvised. I have the sense that you work instinctually.

Lisandro: A lot happens during the shooting that comes from the unconscious part of my mind. Because I’m the director, it can seem as if I’m responsible for what you see on screen. But my collaborators have a big influence on the film. The most important part of my job happens before we start making the film, when I choose my collaborators. Half of the film is already done. Once I’m on location, I simply follow their interpretations of the film. With Jauja, we discovered the film as we were shooting, and for me it was like walking in a new land. I had never made a film like this before or even imagined that I could.

Paul: There is an astonishingly beautiful sequence halfway through the film. Dinesan falls asleep under the night sky, and his body seems to merge with the landscape. Suddenly, we hear music for the first time. It feels as if we’ve moved from the outside world into his mind.

Lisandro: Perhaps he’s dreaming. My sound designer plays in a rock band, and he will often just bring me a song and I’ll just use it. In general, I prefer to use music that’s opposite to the film’s direction. I want to create contrast and to open another window between the music and the image. At the start of La Libertad, you hear this modern disco music, even though the film is set entirely in the forest. In Jauja, the electric guitar you hear is unexpected and it opens another emotional dimension. It becomes another kind of film.

Paul: After waking up, Dinesan follows a mysterious dog that leads him to a cave where he encounters an old woman played by the famous Danish actress Ghita Nørby. The scene is unique in your cinema. For one thing, there’s a lot of dialogue. She tells him a story, but nothing seems to make sense. I wondered what that scene meant for you.

Lisandro: It’s really meant to put us in a fantasy realm. My co-writer Fabián came up with the dialogue. We don’t know who this woman is. Is she the daughter he’s lost, but sometime in the future? Is she the mother of the daughter? Or, is she someone else entirely? Suddenly, we start to experience the same state as Dinesan. He is confused; we are confused; the film starts to get confused.