To watch a Lucrecia Martel film is to be immersed in a world that is equal parts soporific and delirious. Like ‘The Mandrake’, the country house where her first feature La ciénaga (2001) is set, the world of middle-class Argentine society that she examines seems to trudge along in a dreamy, drowsy sleep, interrupted only by glimpses of violence or glimmers of sex. Her films have as intoxicating an effect on their viewers as on her characters. For example, in her latest film Zama (2017) she turned Antonio Di Benedetto’s eponymous novel into a meditation on hopelessness and paranoia. Set in the late eighteenth century in what is now Paraguay, this dreamy revisionist take on colonial Latin American history recasts Martel’s interest in the body politic in the most literal of senses. The suffering, desiring body of Don Diego de Zama comes to represent the land he’s so desperately trying to escape. An absolute feast for the senses, the sumptuous period film still pulsates with that which makes Martel one of the leading filmmakers working today: a commitment to seeing her characters unravel so as to wake us from the restless slumber we’ve accepted as our everyday reality.

Zama, 2017 Actor: Daniel Giménez Cacho as Don Diego de Zama

Manuel Betancourt: I wanted to kick off with an open-ended question that I hope will illuminate our conversation. What inspires you?

Lucrecia Martel: For me, what captures my imagination and really immerses me in the world is the spoken word. The conversation. Words. That’s what I find, well, I wouldn’t say inspiring, but captivating. And the interesting thing is that anyone, no matter if they don’t have any kind of higher education (and that in itself is worth noting), has a way of making language their own. Sometimes people at universities speak in a way that’s actually really boring. On the other hand, if you go to a bar in a poorer neighbourhood you’ll see them using language in such creative ways. I mean, you’ll likely prefer to be in a gathering of people like that – the form of those conversations will be so much more attractive – than, I don’t know, a group of people discussing, say, James Joyce. That’s what’s interesting to me about the spoken word, this oral tradition. It fascinates me, the way people talk.

Manuel: I can see that. I’m picturing a scene at a bar with people sharing stories or family anecdotes, with specific rhythms and cadences.

Lucrecia: Yes! Though sometimes you don’t even have to be telling a story! Take two people talking: everything that’s at stake in their conversation is there, and it’s relevant and charged with so much information that you can immediately gather: what’s the conflict? Who’s the boss? Is there love, is there a lack of love? Is there jealousy? You don’t really need to know what they’re talking about. And that’s important. I think one of the greatest issues in literature and film is this focus on argument, on plot. People think that in order to develop a theme you have to offer it up framed as an argument in an explicit way.

Courtesy film still: © Rei Cine, Bananeira Filmes, El Deseo, Patagonik

…In the middle of that conversation you’re embedding everything about yourself, everything you think about the world…

Manuel: That’s how I felt when I first saw La ciénaga. You’re really just thrown into this world, into these on-going conversations. There’s a degree of disorientation that you adjust to but there are – and this is what I find so re-freshing in it – no moments where plots or relationships are spelled out for us.

Lucrecia: Of course. I mean, this can happen in life, like, ‘Ok, let’s talk about this thing.’ But it’s hard to just talk about one thing. In the middle of that conversation you’re embedding everything about yourself, everything you think about the world. Look, this is something that’s key to my writing. If you have a person talking, you hear them changing their inflection, the pauses they take. There’s all these different forms you have to understand if you want to learn why they take a pause, why they raise their voice. If you want to gloss this phenomenon you have to realize that what they’re saying are merely fragments of other phrases, other people’s words. So, what does that mean? In cinema, for example, every time we have two people talking, you can only capture so much visually. The frame only allows us to capture so much. But what you don’t get in the image, you get in the sound. There’s a complex structure at play there. And when you focus on that, you find all these new kinds of structures that have yet to be explored. Instead, I see people constantly focusing on timelines and organizing plots. This talk of, oh we need to have a ‘turning point’ here or I don’t know what else. That doesn’t happen. It doesn’t exist. Or, rather, it exists but it’s a construct. What real people do is more original, it’s more important. These days, young people, and young filmmakers in particular, are always trying to shock and make things that call attention to themselves. In Argentina they watch and try to emulate Asian cinema, but what’s right around the corner is much more innovative than what you get from watching Hong Kong cinema.

Manuel: This just makes the opening of Zama feel all the more prescient. You open with a scene where Zama is trying to overhear the conversations of this group of women who are taking a mud bath by the sea.

Lucrecia: And yet he’s accused of being a voyeur (‘un mirón’)!

The geography of the body: that’s fascinating to me. Especially if you approach it as something unknown.

Manuel: Yes! It struck me as being emblematic of the kind of cinema you’re describing, focusing on sounds. But, of course, and this is what I wanted to talk about, in that first moment there’s also a focus on the body, which is so central to your work. What draws you to the body?

Lucrecia: I was just asked something very similar. Why is that? Because, I see the body in all the cinema I watch! Just in the past few days I was watching some of these, you know, action films, like Thor and such. There’s a great many bodies in those films. But why is that body not valued? Let’s say the hero or heroine is technologized. You know, either explicitly like Iron Man or Ant Man, or in more subtle ways, like Black Widow’s hyper-trained body. But why do we not care as much about those bodies?

I’ll tell you what I think: these films are made with ideas about things, but without a sense of curiosity about the body. When I film I do so with a curious take on the body. Suppose Hollywood were to knock on my door tomorrow and say to me, ‘Look, you can shoot a film on the moon or over there in India with a cast of 400.’ I’d take the India gig. The geography of the body: that’s fascinating to me. Especially if you approach it as something unknown. Not like, ‘Oh, yes, she’s a middle-class woman and she’s like this and like that’ or ‘Ah, of course, he’s a sexist macho guy’, or I don’t know what else. If you approach it that way, you’ll never be surprised by a body. But if you think about it as a monster, like a creature that you’ve never encountered, that you don’t even know how it moves – like when you stumble onto some sea critter that you’ve no idea what it is, that you don’t know whether it’ll jump or crawl. If you don’t know, you approach it with caution, with fear. To me that’s a great attitude to have when shooting the body. As if you had no idea whether it’ll grow another head or if it’ll stretch itself. I mean, I’m exaggerating but this idea of the monster is key to my writing and my filmmaking. People tell me all the time, ‘Oh, Zama is your first film with a male protagonist’ and I swear to you, I never once thought about that! Because to me that’s irrelevant. Because, if you’re thinking of the body as a monster, then it really doesn’t matter if it looks like a man or a woman. The monster, as a desiring organism, is a much more useful framework to think about bodies. And once you begin thinking that way, the body gains more depth.

Manuel: I think it’s also about the fact that your characters truly are desiring monsters; they’re guided and shackled by their desires.

Lucrecia: Well, there’s no law when it comes to desire. You can’t dictate desire; this more or that more. You never know. No one can be crazy enough to confess their innermost desires. Because no one desires in only one way. That is an absurd thought to have about any living thing.

Manuel: That’s so central to your work, where characters are often negotiating their impulses and desires with the strictures around them. They’re constantly trying to—

Lucrecia: To break out! Yes. And I think that about people. It’s not just that I put these things in my movies. I believe that we’re constantly hoping to seem like trustworthy people. Oh, I’m a man who likes men, or who likes women. You want to appease those around you, comfort them in a way. Now imagine if we all allowed desire to run amok. It’d be total chaos (‘un quilombo’)! It’d be more fun but it’d be a disaster. Capitalism wouldn’t work. So we had to organize that. And we lost a lot – but hey, we have an iPhone X.

Manuel: Capitalism on the one hand, but religion, surely, on the other.

Lucrecia: Oh, but watch out! Because religion and capitalism are intricately connected. Capitalism is a religion very much modelled on that other one. But without a doubt religion needs to establish limits and above all frustrations. If a religion doesn’t generate frustrations, it cannot dominate. You cannot dominate those who are satisfied. It’s a lot easier to exercise power over those who are dissatisfied.

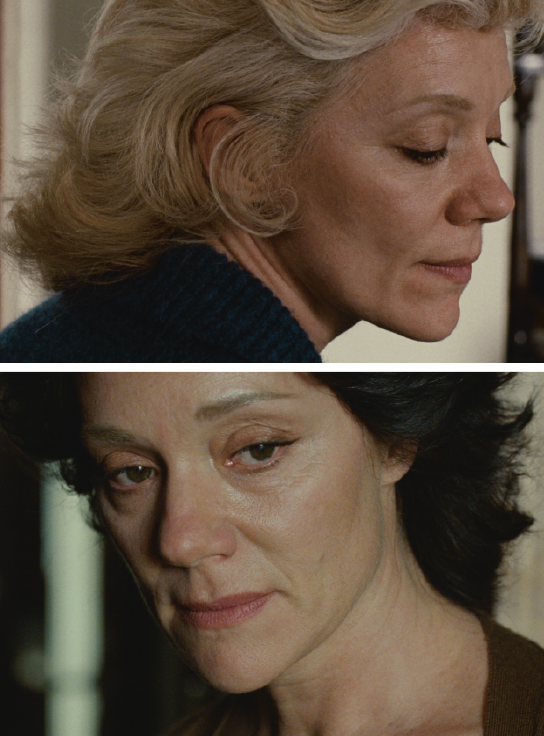

One of the greatest strengths of Lucrecia Martel’s film The Headless Woman (La mujer sin cabeza), 2008, just may be its ability to say an incredible amount without the need to verbalize anything at all. Hailed as a masterpiece of its time, and a seminal text in the Argentinean New Wave, Martel’s film explores the internal breakdown of a middle-class woman after she hits something while driving her car out on an isolated road. First believing it to be a dog, but slowly forced to confront another possible chain of events, Martel’s protagonist slowly becomes the ‘headless woman’ of the title. The Headless Woman gives little insight into its characters, including Veronica (Maria Onetto). She is introduced only a few minutes before her car accident, and the information about her revealed afterwards is neither extensive nor explanatory. After hitting the object (dog or person), Veronica goes to the hospital. She meets her husband’s cousin, Juan, in a hotel room where the two of them have sex. It’s unclear whether this is the first time this has happened, meaning there is little to insinuate from this relationship. Is this the first sign of Veronica’s guilt manifesting, or is this a part of who she was before? It’s almost impossible to know.

Courtesy: Becky Kukla Vague Visages

Manuel: What happens then when, as you do in Zama, you take the Church out of the equation? When you imagine a historical past that’s purged of Catholic iconography?

Lucrecia: Well, our past in Latin America has been very much entangled with the Church. And so I thought, what would happen if we extricate it? What would we see? It was a great exercise for me. The only reference to the Church I left in was this priest character who spends his time just talking about money.

Manuel: And who is basically a bureaucrat. But I’m curious since, for many of us who grew up with the Church, this image of bodily suffering has been so tied to Jesus Christ. What are we left with when faced with a character like Zama who suffers and is forced to sacrifice so much when seen outside of a Christian framework?

Lucrecia: What I was afraid of, especially because towards the end we get to see Vicuña, you know, all draped in red like the devil, was that you’d think of Zama as a Jesus-like character. Which is why I left this one line in, one I’m not really a big fan of. It’s when he says, ‘I say no to your hopes.’ Because I wanted to make it clear that Zama is for everything that the Church stands against. And so while there’s this moment where it might look like he’s Jesus and he’s facing the Devil, the Devil we have is decidedly more human. I was afraid of that reading.

A moody, moony parochial-school student named Amalia (María Alche) comes alive when a stranger rubs up against her in a crowd. The culprit happens to be a prestigious doctor, who is staying in a hotel run by Amalia’s divorcee mother for a medical convention. Inflamed by a combination of warped love and curiosity, the pious-perverse girl begins to stalk her molester with a clammy ardour. Martel’s provocative second feature more than fulfils the promise made with her brilliant debut: The Holy Girl is a coolly knowing dramatization of the thrumming sexuality of teenage girls, drawn in equal parts to religious fervour and erotic mischief.

Courtesy: Film Society of Lincoln Center

Manuel: Because there is no hope in Zama.

Lucrecia: Well, because to wait, to hope (‘esperar’) is very much a thing of the Church. If you want to make the body suffer, you at least have to generate some hope. But if you don’t have hope, if you’re not waiting for anything else, then you act. The present becomes much more important. With hope the only thing that matters is the future. Every day may be torture but then you’re always looking ahead, deferring to some nebulous future. That’s the Catholic Church: in the end God will reward you, and in the meantime, you have yourself a shitty life.

Manuel: It’s this idea that your suffering will be worth it.

Lucrecia: The Church’s catechism, I guess they changed it recently, says that people who experience same-sex desires should not, at least not any more, feel ashamed. That they’re not sick and have nothing to be ashamed of. But what they do have to do is abstain. And so what’s the life they’re proposing you have? One where at the end of the day God will reward you for that abstinence? What kind of life is that? This idea of hope in the future is very Judeo-Christian. Instead, to vindicate the present, to rebuke hope, is radical: if, in your daily life, you are not enjoying yourself then you have to make some kind of change now. You can’t postpone that.

Manuel: You can’t wait for God or anyone else, the way Zama does for so much of the film.

Lucrecia: You can’t wait. Because the only thing that suffers when you defer is the body. And since the Church thinks that’s utterly worthless, well, then there’s no problem torturing one’s body.

Manuel: Speaking of people who indulge their body, one of my favourite characters in Zama is Lola Dueñas’ Luciana Piñares de Luenga.

Lucrecia: Let me tell you this. What she brought to the part, it was so great. She played her like a rather ordinary woman dressed up like a queen. Because you have no idea how many whores, really there’s no other word for it, came over to America. But since they were light-skinned they became these well-to-do women around here, these señoras. Their origins may have been humble but here they were treated like queens. So she added that aspect to Luciana and I loved it.

Manuel: The line I loved was when she says she hates her body because it’s so coveted.

Lucrecia: She says, ‘I despise it. And all men for their desire to possess it.’

The man in that film would be crucified today, but she turns him into her object of desire. And that makes her feel powerful instead of being horrified and feeling humiliated, which is how we’re taught to feel in those situations…

Manuel: This vexing relationship to the desire that her body inspires strikes me as central to your other films as well, where desire always comes with some baggage and yet it suffuses the worlds you create. And it’s always more unruly than your characters realize.

Lucrecia: Well, think of La niña santa (The Holy Girl). The man in that film would be crucified today, but she turns him into her object of desire. And that makes her feel powerful instead of being horrified and feeling humiliated, which is how we’re taught to feel in those situations. Because it’s like, why should I feel ashamed for something an idiot did to me?

Manuel: In a similar vein I wanted to talk about the relationship between Jose and his sister in La ciénaga, which the film really dances around. It’s sort of…

Lucrecia: Sexual.

…negotiating one’s desires, organizing them – that’s impossible to do. It’s like trying to hold water with your hands…

Manuel: Yes. But the film never quite condemns or judges it.

Lucrecia: Well, that’s because in general I don’t judge anything like that. Like I’m telling you, negotiating one’s desires, organizing them – that’s impossible to do. It’s like trying to hold water with your hands. You can’t do it.

Zama, 2017 Actor: Daniel Giménez Cacho as Don Diego de Zama

Manuel: With that in mind I wondered then what does a cinema that takes that into account look like? What are the kinds of films you hope to make in the future to continue that project?

Lucrecia: Right now, I’m working on a kind of science fiction piece. But it’s like a melodrama where technology is so sophisticated, so extraordinarily advanced that you don’t notice it. And what I like, what I am really trying to do is to break down the dynamics of the relationships we see in melodramas. Which is very easy, because they’re so pigeonholed already: in the end no one is anything. All the time we’re acting and wanting to seem a certain way, to appease others, but also to not go insane ourselves. But no one is anything very concrete. And I love that.

Manuel: We only ever congeal into something when faced with another, with an audience or a partner.

Lucrecia: Right. And that’s a very loving part of the human species. We’re always trying to gain someone’s trust, so as not to frighten them. Well, except for evil people who’re always intent on instilling fear in you.

Manuel: But even then, they need the other. Which brings me to something else I wanted to discuss, which is your work with actors. The performances in your films are quite loose and vivid. There seems to be quite a bit of trust there. What’s your approach to working with actors?

Lucrecia: Listen, what I do is, if I’m working with a professional actor, I just respect their process. I try to just follow their lead. And if they’re non-professional actors, well, I try all sorts of things. You know, getting them to do the lines over and over, asking them to just emulate me and my line readings. Anything to get it just right. But, really, I don’t have that many tricks. I don’t know anything about directing actors. What I do know is how to talk to them, how to strike up a conversation with them. And not just with them but with the crew. That’s it to me. You need to be able to engage with them. To listen. There’s not much science to it, really.

…how they move in and away, how one’s posture changes when you’re near or far from one another. All of that is immensely seductive to me…

Manuel: So many scenes in your films hinge on these large, sprawling ensemble moments. You thrive in these moments when you’re tracking a large group of people on screen. And you know, you joked about picking the India project with 400 people over the moon flick, so I was curious: what draws you to crowds?

Lucrecia: I just love it. I love when you have that many people in one place. It’s like that pastime we all have when we’re in some long queue, when you take a moment to see how it organizes itself. You notice how there’s a gap here when some people went forward but others haven’t noticed and then these over here start moving and then it ripples out onto wherever you are. There’s a collective consciousness there. It’s one that I could choreograph in a film but it happens in real life. It’s fascinating to see how human beings behave when in such close proximity, how they move in and away, how one’s posture changes when you’re near or far from one another. All of that is immensely seductive to me. One of my guiding ideas is this concept of immersion, of being submerged in something. I can’t ever think of individuals as being completely detached from one another. It’s as if we were all connected by the air or by water. Every movement you make ripples out into the other. I love that. And I do love building these scenes with lots of people, lots of characters. Those are my favourite days to shoot. I have a lot of fun. I actually get quite overwhelmed when I have to shoot scenes between just two people – like those scenes where it’s just Luciana and Zama. Those were the hardest for me. There’s quite a bit of dialogue but, really, scenes with just two people are much more difficult. It’s a different kind of tension. To me it’s easier to weave a more intricate tangle, a bigger tapestry.

Manuel: It also allows you, I think, to put into motion a lot of political issues, which we haven’t really talked about. In tandem with your focus on the body, your films tackle issues of class and it strikes me that these may be related: that your cinema is interested in how politics comes to bear on the body.

Lucrecia: You know why? Because of a very simple idea. To me cinema is an artifice, totally contrived, that reflects reality badly. A little crooked. And in that twisting there, a movie allows you to see that reality is also an artifice. One that thrives because there’s a huge consensus about it. We all go out on the street, see a car coming and know it will stop for us. Why are we so sure about that? Why are we so sure that we’ll head out and some neighbour won’t throw their flower pot out the window? Because we’ve built a consensus so grand that we’ve forgotten it’s a construct. What’s artificial about our own reality, and how we’ve come to normalize it, that to me is our greatest problem. And that’s why I make films. To go back and understand that reality is an artifice. That’s the political purpose of cinema. You can follow a path that’s arguably a lot of fun or you could, you know, make a Meg Ryan (oh, it really hurts to take a dig at her) romantic comedy. That conflict you see in those romantic comedies is all about ‘love’ but there’s never any critical inquiry into what surrounds it. There’s only curiosity for this idea of love, of romantic love, a kind of limiting notion of desire. So you can make those kinds of films that merely reaffirm your reality, or you can make films that critique it. That’s the cinema I love, the kind that reckons with and questions reality.