The X-rated animations of Wong Ping seem to hail from an alternate, though strangely familiar, dimension. Taking you by the hand, he leads you on a joyful frolic through perversity: a married man who spies on his wife having sex from a closet, a teenage boy who has a crush on a classmate with backwards-facing breasts, or a chicken who is addicted to social media. Comically sinister plotlines are partnered with cartoonish aesthetics and layers of electric colour. Within this discordance, a geometric landscape blossoms where bodily fluids and profundities float, soundtracked by mechanical whirrs and bleeps. The fabulistic tales flirt with the social and political expectations of Hong Kong, in his words, toeing and even passing the line of acceptability.

Yet beyond this, the explicit content is a celebration of amorphous bodies and the universally kaleidoscopic nature of desire. When I call, the city-state is at the height of its restrictive COVID-19 lockdown and in the midst of ongoing civil unrest. I find Ping alone in his studio, where he admits that he cannot recall the last time he spoke out loud. We move through the digital realm, touching on pornography, Otaku culture, and how dating apps have sparked connections between strangers. He elaborates on connectivity and closeness, pondering how such themes have taken on an even greater precedent as we grapple with a new reality shaped by months of physical and mental isolation.

Holly Black: Despite being inherently surreal in their nature, your animations are also rooted in the banal aspects of existence. You draw on the events of everyday life, particularly the more unusual goings-on that can be spotted among the routine activities of Hong Kong. Have you seen any particularly out of the ordinary things happening during the lockdown?

Wong Ping: To be honest, I am less inspired during this period because the world is becoming the same everywhere. On some level, we are all dealing with the same isolating experiences and stress. People aren’t going out that much, myself included, and it’s the same online, influencers have less and less to post. It seems like artists are just doing a lot of cooking. I can’t even remember the last time I spoke out loud. As I live alone and I’m single, there has just been a lot of texting, which makes it hard to feel connected to people.

Holly: How have those around you been adjusting to isolation?

Ping: My friends who work in offices in Hong Kong are bored, frustrated and emotional because they are stuck at home. They hate being trapped inside for any length of time, particularly because they tend to live in small and densely packed apartments. This type of person needs the working system; the routine of going to an office and suffering, followed by the pleasure of a vacation. It is different from my experience as an artist, working independently, with an all-encompassing practice.

Holly: The idea of the crowded metro-polis – living on top of each other – recurs a lot in your animations. You have people peeping through holes into their neighbours’ place or gazing through a window. It’s voyeuristic and clandestine, but also fun and even a little bit creepy, as if each threshold is a portal into another world.

Ping: In Hong Kong, we live in such high density. We come across each other a lot, and see strange things, because no one has their own space. I once saw an old man in a park getting rid of a bin bag of old pornographic VHS tapes, which inspired Dear, Can I Lend You a Hand? (2018). He had to throw them away somewhere!

Holly: When you first started producing your animations, were you naturally drawn to creating stories that explored ideas around sex?

Ping: I have never really understood why discussing sex should be taboo. Of course, it’s not the kind of thing to talk about with your parents, but the internet always seemed like a free place of expression. To begin with, I was creating videos in my spare time, which included these ‘naughty’ images and ideas, and started posting them online. You see a lot of content out there on the web that is much more extreme than my work, so I didn’t expect anyone to pick up and discuss this aspect. And of course, it is important to remember that I haven’t actually done these things, they are just stories.

Holly: Your work has been heralded as radical in its approach to articulating explicit intimacy. What is the general attitude towards discussing sex or engaging in public displays of affection in Hong Kong?

Ping: It’s not as extreme as other places such as Japan, however, we don’t tend to be overly intimate in public spaces. Holding hands and a bit of kissing is fine, nothing too long or intense. Hong Kong’s mainstream media is certainly conservative, especially when it comes to showing skin, and we don’t really talk about sex. But when you go on the internet and social media it’s clear that we share the same desires and thoughts, we just don’t say them out loud.

I grew up reading manga, which often deals with sex – my favourites include the works of Suehiro Maruo and Namio Hurakawa. Hong Kong doesn’t really have that outlet. We have shops that sell pirate copies of Japanese pornography, but they are clustered in a particular area, and I’d say that there are less than ten places in the whole of the city.

There is also a special type of publication, a kind of photo book that features a particular model – such as members of the pop music group Nogizaka46 – posing in different sexy outfits, in beautiful and exotic places.

Holly: I suppose the only comparison would be a pin-up calendar?

Ping: Yes, with firemen! This version is more similar to an artist book, with high-end photography. There have been many conversations around banning this genre at book fairs. The government is hyper-sensitive about this idea of exposure, as are the older generation. You have to ask, where is the line? Who gets to decide what is allowed?

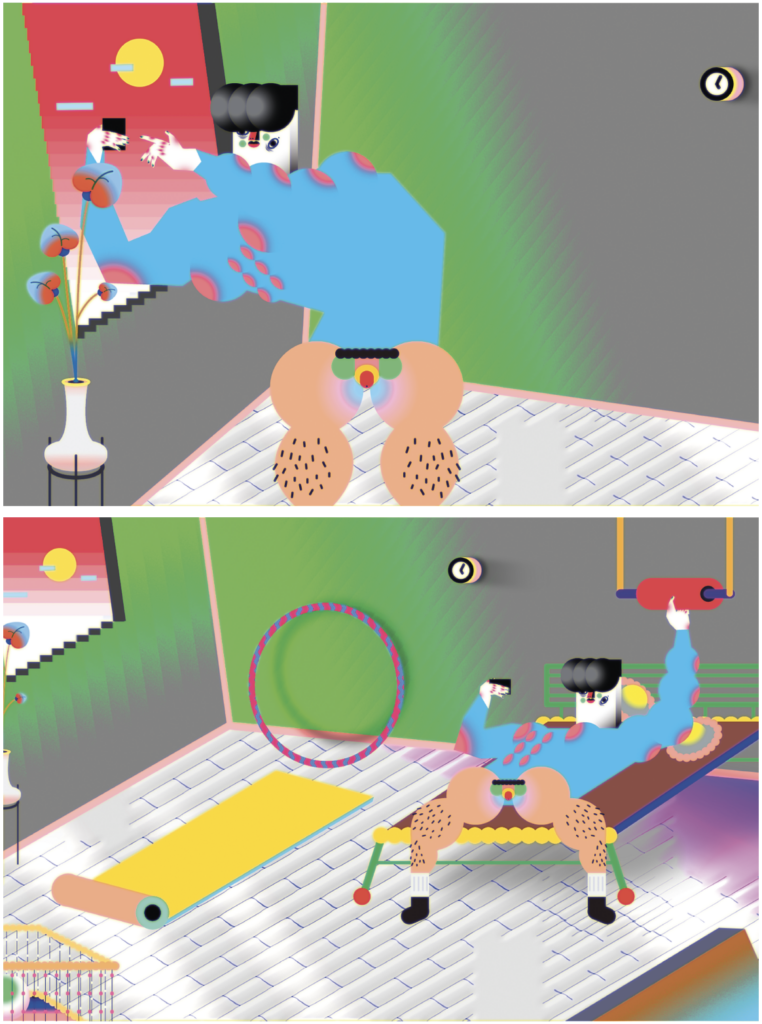

The inspiration for Who’s the Daddy is an apparently innocent popular children’s song about fatherhood. A bad match on a dating app leads to a roller-coaster of emotions, full of suppressed sexual desire, fear and perversion, all presented with disarming openness and humour. Initially, its playful appearance also conveys a sense of infantility. Any hint of innocence

is however counteracted by the dark, dystopian undertone of the narrative – a man recounts his humiliating experiences

in a partnership. Through a dating app, he finds his ‘match’ in a devoutly religious woman with whom he starts a relationship, only to find that he can draw satisfaction purely from his own submission. Powerless, he surrenders to her perverse

sexual cravings and takes on the role of a single parent. Courtesy: IFFR

Holly: I’m drawn to what you create because it’s often so comical. It is amazing to see people snicker and giggle in a gallery space, where you are expected to be deadly serious.

Ping: It is meant to be fun, although I’m not saying that there isn’t a bitter side to sex and relationships. I’m not only approaching the joyful aspects. Rather it’s about showcasing something that is complicated, and of course, not limited to one idea. I don’t think anyone believes I’m explaining how you should make love, like an instruction manual for assembling Ikea flat-pack furniture. Everyone has their own fetish, and I use sex and desire as a language to expand and talk about other issues.

Holly: As you say, there has been much discussion on the graphic elements, yet it’s true that you are grappling with universal themes. It’s not like you’re simply animating a porno movie. You tell stories of love, jealously, isolation and aspiration.

Ping: That’s why I find it very hard to explain the synopsis of my scripts. The process is much more like writing a diary. I don’t really have a singular goal or idea of what I want to say. It is a real mixture of everyday life, which I know is a source of inspiration for so many artists and scriptwriters. In my case, I just don’t have a final statement, I never really know what the end game is.

Holly: Can you share some thoughts on why you choose to work alone?

Ping: So many artists work alone, at home, in complete isolation – it comes naturally. In my case, it is the same before and after the pandemic. Also, drawing is difficult for me. I can’t articulate motion very well and I find it hard to explain ideas to other animators. Over time I’ve realised that I have to go through the process myself, in order to get to the end result. If I had a storyboard and a team of assistants I would be stuck in my original plan and wouldn’t be able to make significant choices along the way. It’s like making a sculpture, you have to turn it around and carve it yourself. You could send it off to be made by a machine, but you wouldn’t be encountering the problems that make the end result better. Animation is a form of craft; you just happen to be creating with a mouse.

Holly: While you have a unifying aesthetic, which has been likened to movements such as the Memphis Group, everyone looks very different. Figures are made from strange assemblages of shapes and colours, and many have surreal body geometry, such as a young woman with breasts on her back in Doggy Love (2015) or a blue gentleman with a lumpy, bulbous head in The Other Side (2015). How do you settle on the visualisation of your characters?

Ping: The art world isn’t really my background, so when people mention various artistic references, I don’t always make the connection. It is like when you visit a psychiatrist, they will unlock lots of things you never knew were there. The same goes for comic books and video games. Although I am much more informed by the storytelling qualities of these mediums as opposed to the aesthetics.

My process begins with the narrative, at which point I don’t have any distinct visuals. Once that is finished, I shut off the writing department and just draw on my computer, creating anything that seems fun and exciting. My intent is to never be too obvious, so if I’m thinking about a football player I don’t want to produce a typical muscular guy. Everything needs to be unrelated, that is what creates the chemistry. I am creating what brings me joy.

Holly: What about your heart motif, which looks similar to an unhappy emoji? It is a recurring presence, and even crowned your Boner (2019) sculpture, the phallus you installed on top of Camden Arts Centre.

Ping: It all began with my first offline, ‘real world’ exhibition at Things That Can Happen, an art space in Hong Kong, which gave me the opportunity to produce something three-dimensional. I built Boner in my tiny flat, incorporating this unhappy, upside-down heart at its tip. Perhaps I’m dealing with some unresolved relationship troubles because I see it is a symbol of both joy and suffering. In Doggy Love I speculate on where the image of the heart comes from. It could be informed by the sexy shape of a woman’s buttocks, or the look of your lover’s lips when you lie down next to them. Now it also relates to social media ‘likes,’ connecting to ideas of loneliness, desire and love.

Holly: How do you go about gathering your material? Some artists write or sketch in notebooks or take photographs?

Ping: Until a few years ago I kept everything in my mind. As I’m getting older I find it difficult to rely on memory alone. Instagram has become a way of referring back. I might see graffiti in a public toilet, for example, and I just take a photo.

However, it can be challenging because there is so much pretty content on Instagram, and when you’re exposed to so much amazing work it is hard to move forward. The more I see, the more stuck I get. I think everyone experiences that, for example, when you read a lot you might worry that you are just repeating what someone else has already said. I’m a bit concerned about losing my instincts, which are really important in terms of inspiration.

The short film tells the story of an impotent husband, unsatisfied wife and a megalomaniac policeman, illustrating the perfect ecosystem of the concrete jungle, where these characters are able to truly face their lust with no moral laws. Flashing, pop-like imagery; visual and auditory narrations that explicitly touch upon sex, politics and social relations; vibrant sculptures that extend into three dimensions the artist’s fantastical animation world that combines the crass and the colourful to mount

a discourse around repressed sexuality, personal sentiments and political limitations. Courtesy: Art Basel

Holly: There’s a strong sense of playfulness: the naivety of the graphics rubbing up against your deadpan Cantonese voice-over telling these bizarre tales. Could you elaborate on this schism?

Ping: I tried to act out different characters, like a typical voice-over, but I absolutely hated it. I cannot act! So, I just thought, ‘fuck it, I’ll just read it.’

Nowadays it just requires one or two takes, and always in the same rhythm. You’ll notice I read fast too because I hate listening to my voice. The combination really works with the minimalist animation style I use. I have one particular type of ability that I want to push to the nth degree, as opposed to chopping and changing. Actually, writing is the most enjoyable part for me and it’s what I spend the most amount of time on.

Holly: It’s like you said before, sometimes too many possibilities can be overwhelming. Also, your stories are very elaborate. I’ve heard that your two Fables series (2018–19) were inspired by the Aesop originals?

Ping: Yes, I learned abut them when I was a child. But I didn’t research further until much later. Most fairy tales have been modified by Disney and the like, to make them more palatable. When I started working on the fables I wanted to follow the same line, to make them cleaner than my previous animations – less blood and sex. It was another exciting limitation. I wanted to write something that was structurally weird, without utilising such in-your-face graphics, informed by films like Funky Forest (2005) – a crazy and surreal collection of stories. When I was researching Hans Christian Andersen I found out that in his diaries he made a mark whenever he masturbated, and he liked to go and meet women, shake their hands, and then go home to jerk off. He’s using the same hand to write these fairy stories.

Holly: That’s both intriguing and a little bit unsavoury. I see a parallel with your work, there’s a magical and joyful sensibility, that can be undercut by A something gross, such as in Stop Peeping (2014), when a woman’s sweat is turned into ice lollies.

Ping: I thought making ice lollies from the sweat of the person you admire signifies love, that’s how I thought you could express it.

Holly: As you say, everyone has their own fetish or manifestation of love and affection.

Ping: Our conventions of expressing love come from classic TV and movies. Actions of affection are an international language. We all end up doing the same thing to emote on a basic level. Of course, nowadays people don’t watch shows in the same way, which makes me wonder if we are receiving these messages differently.

Holly: You make use of some interesting references to digital communication. Have the ways the internet shapes intimacy and relationships been an influence?

Ping: It would be impossible for it not to have an effect, it’s one of the biggest changes we have seen in our lifetimes. In my opinion, we benefit from the way we interact digitally. For instance, in Hong Kong some of my friends are meeting foreign partners thanks to dating apps, it would have never happened before because they move in small social circles. This makes it difficult to meet someone from a different background.

Holly: Previously you have mentioned a connection to Otaku culture: the idea of an obsessive fan, particularly of video games or anime, who might shut themselves off from the world and exist predominantly online.

Ping: There are lots of different forms of Otaku, but my work definitely has a link to an ‘indoor’ lifestyle that has become more visible to the mainstream, one that is surrounded by video games, manga and animation. There are fears that these forms of pop culture are detrimental to the way we communicate, but I see it as a positive. Thanks to the internet, we are able to select who we spend our time with like never before. You can text while having dinner with a friend, which means you are building more than one connection and can cherish them both. Likewise, if someone wants to spend 24 hours playing a video game, they are choosing to treasure that experience instead of communicating with other people in ‘real-life’. I don’t think that is a bad thing, as it’s a different form of interaction.

Holly: Although women are frequently the objects of desire in your animations, they are also sexually empowered and very decisive. For example, the wife who takes control of her own needs in a sexless marriage in Jungle of Desire (2015) or the high school girl in Doggy Love who is not ashamed of her body. I find your representations liberating because, in sexual imagery, women are often still subjugated or have to fit a particular beauty ideal. Do you create strong female characters deliberately?

Ping: It is interesting that you say that because there are some who find my work quite controversial. In Doggy Love, for example, I have been accused of objectifying the female character because I’m talking about her purely through sex. However, I see sex and intimacy as enjoying an act together. Of course, the narrative is from my point of view – that of the man – and although it has been suggested that I should insert other female voices, my narration is like a diary, so it would feel super strange to have other points of view running through. In Who’s The Daddy (2017) the male protagonist is the one being dominated, he is enjoying being ordered around by a woman. From my perspective, that is an enjoyable process. Others might interpret it as problematic because I portray her as ‘evil’ – but I am attracted to women like that. I also think that this perspective assumes I write these stories without much consideration, when in fact I spend a long time thinking about them. I don’t want to back down just for fear of what others might think, but at the same time, I am not going to make a huge statement about these complex topics. I toe the line, even stepping over it a little bit. At the end of the day, it is up to the audience to interpret the work on their own terms.

…Hong Kongers engage with my work on a more playful surface level, while other audiences might understand the more entangled messages around politics, relationships and social media culture…

Holly: There are many different access points, not to mention layers of complexity, so variably subjective interpretations are understandable.

Ping: It is also important to stress that my work is easier to digest because it’s animation – it can never be that serious. Even if I say horrible things it is often seen as a joke. An audience might get the meaning, but the cartoon filters out the darkness and focusses on the funny side. After one of my first shows, a critic emailed me and said he felt uncomfortable with my work because the viewers didn’t ‘get the message.’ He had decided to ignore the visuals and focus solely on the dialogue, so everything came across a lot darker. As a result, he didn’t approve of the other viewers who were laughing. In Who’s The Daddy a woman has an abortion, but I’m not trying to take a pro-life or pro-choice stance. It is much more about the ideological problems you bump into when you are online dating. Abortion is going to come up in a lot of relationships, but this critic argued that it was too sensitive a subject to cover. Perhaps it’s a cultural thing. In Hong Kong a termination is not bonded to religion or ethics in the same way as some other nations, so even though you might not talk about it openly, you are likely to discuss the implications on health and wellbeing, and the impact on your partner or friend.

Holly: Do you find you get different reactions depending on where you show?

Ping: I think Hong Kongers engage with my work on a more playful surface level, while other audiences might understand the more entangled messages around politics, relationships and social media culture, which are often full of sarcasm. It would be easy for a single line to be picked out of context and for full outrage to ensue.