The erotic quality of the oeuvre of visual artist and writer Tim Etchells is perhaps not immediately apparent. Though it is conceptual in nature and precise in execution, his visual work, in particular the neon signs, does confront us with (crude) semantic slippages and has a playfully subversive streak to it. The neon tubes that Etchells uses to spell out his tongue-in-cheek sentences may share some hardware kinship with those used by minimal artists such as Dan Flavin, but are actually more closely related to those iconic works by the king of the neon provocation, Bruce Nauman. Whether making posters for public display or creating theatrical performances, Tim Etchells shows us that language is hard at work to entertain our filthy minds. Basking in the blue glow of our screens, we sat down to explore the sensuous seduction that lies beneath the surface of language.

Samuel Saelemakers: If you’d allow me to say so, I would like to state that words are the main material of your practice, which makes use of various media or formats such as performance, neon signs, photography, and others. And while your work for both on and off stage is always highly visual, I wanted to ask where this preference for words over images comes from.

Tim Etchells: I think I just have a kind of gravitation to language, I don’t really know why. From quite a young age I was fascinated with words and bound up with them in a certain way. Important here is that working with words means also, for a big part, working with how people receive them or complete them. My work is always an offer but there is always a lot of space for the viewers to do their own imagining or thinking. I like that a lot about language, how it makes a proposition and how you as a viewer or reader are invited or obliged to finish things.

…I do think of them as works that at least aspire to a kind of intimacy…

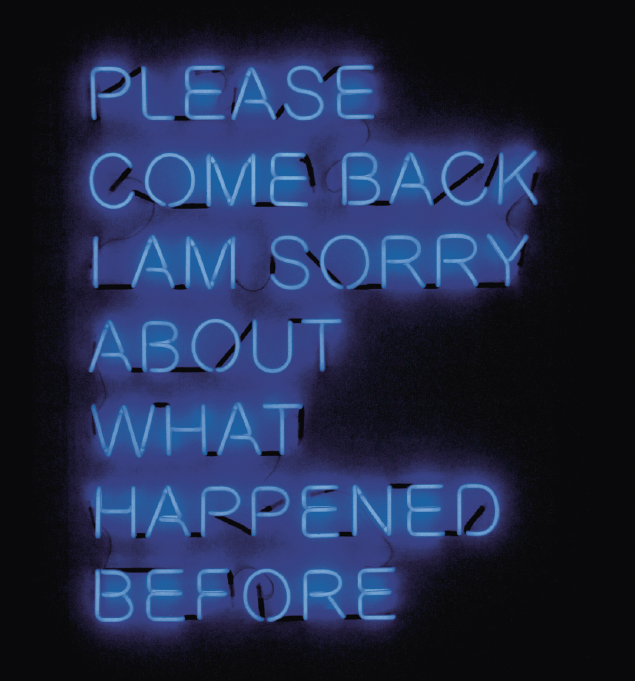

Please Come Back, Neon sign 2008 Courtesy: the artist

Samuel: The tension between inviting and forcing someone is quite present in your work overall, I think. Let’s talk about the form of direct address, which is especially present in your work using words in print or letters as objects. The neon works or slogan-like posters are striking visual units of meaning; they come across initially as bold one-way messages. Does this boldness sometimes make it impossible for these text-as-image works to convey the intimacy or fragility that is present in your theatre work?

Tim: By its very nature performance is a live situation, and entails an exchange of sorts. There is always a person in front of you, so everything is embodied and fragile, existing as a process. Of course, in a way the text sculptures are more solid – they’re objects rather than processes or events – but I do think of them as works that at least aspire to a kind of intimacy. While they are relatively solid propositions in language, conjuring an image or an idea, there is also always a kind of incompletion there: a puzzle or an ambiguity for individual viewers to negotiate or resolve for themselves. There is a lot of intimate space in that. If you think of the three earliest neon pieces I made, back in 2008 – ‘WAIT HERE I HAVE GONE TO GET HELP’, ‘LET’S PRETEND NONE OF THIS EVER HAPPENED’, and ‘PLEASE COME BACK I’M SORRY ABOUT WHAT HAPPENED BEFORE’ – they are all statements proposing a relationship to the viewer that in one way is quite narratively charged but also completely unclear. What happened? What’s at stake? Who’s talking to me?

Samuel: Could you think of them as incomplete speech acts? To be completed?

Tim: Absolutely, in that sense they offer an opportunity for the viewer to step in there, into that speculative intimacy.

Cathy Naden and Claire Marshall in Showtime Photo: Hugo Glendinning

Samuel: Could you talk a bit about a recent project you did in Leeuwarden, significantly titled In So Many Words?

Tim: The project consists of several related elements, the first of which is a large neon piece consisting of eighty different terms for what people do with language and with voice. Some of the terms are rather technical or pragmatic, while others are more narratively or relationally charged: sing, whisper, shout, tell, ask, confess, describe, instruct, pray, or promise. It was an attempt to think about the different things we do with language, creating category headings with the idea that viewers might do their own work in fleshing those categories out, thinking how they might apply to them or to other people.

The second major element of the project is a sound installation across ten speakers featuring about seventy different people speaking the alphabet in a language that they know and giving example words. Here the work deals with the formal system and restrictions of language and its potential. But also, each person was recorded without preparation, improvising those texts, associating from one word to the next, A – apple, B – balance, C – car park. But we also got access to the intimate turns in their thinking: where they were delighted or surprised by a word choice, or when they really couldn’t think of something to say for a particular letter. So, although it has a formalist feeling in one way, the work is also extremely intimate in regards to the people who are speaking. I also played with putting those different alphabets across the ten speakers in a kind of dialogue – creating something that plays with semantic slippage, connection and disconnection as well as with a kind of musical or textural interweaving of the languages. So, the voice speaking French might appear to be answered in Korean, or the German and the Welsh voices might appear to argue, agree with or call to each other.

Samuel: When touring internationally with some of your works, such as the poster series And For The Rest, which you’ve shown in Brussels, Basel and Athens, do you feel there is a different functioning or expectation of language?

Tim: I think one thing you can feel is a shift in sensitivities in different countries. I did a poster series for public space in Utrecht, creating pieces from my Vacuum Days series, which is pretty confrontational, politically speaking. The posters announce absurd events, with a kind of Dadaist energy, funny in an unsettling way, often using the names of real figures from contemporary politics or celebrity culture. One of the posters announced: ‘Geert Wilders’ Peroxide Solution’ and went up around town, in the tram shelters and so on.

I’m not sure those kind of posters would have been shown like that in the UK! They’ve been shown in galleries but the approach to public space here is more careful, more timid.

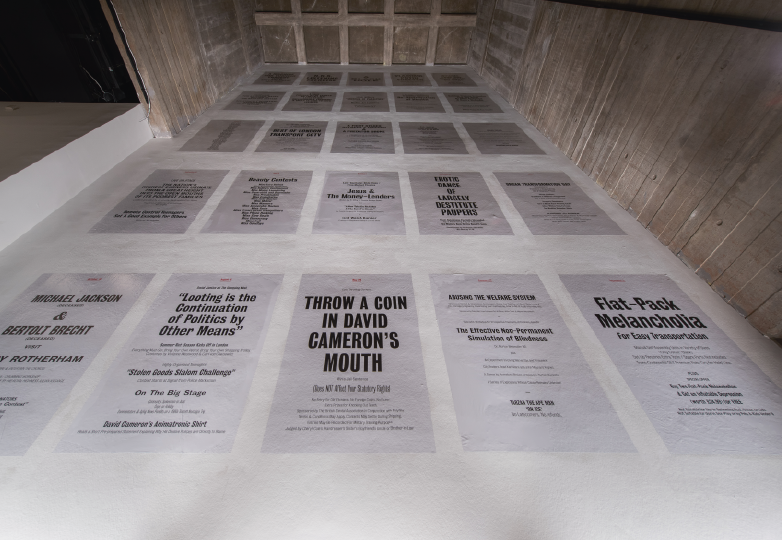

Vacuum Days Posters, poster Series 2013 Photo: Hugo Glendinning

This series of posters comprises entries taken from Etchells’ online project (2011) and publication (2012) Vacuum Days, and reproduced as A0 prints. Spelled out in overzealous capitals and small print, Vacuum Days (Posters), offers choice selections from a zone of sensationalist media, news-as-pornography, hyped-up current affairs, Internet spam, Twitter gossip and tabloid headlines. Courtesy Tim Etchells

Samuel: Speaking out in public space is a very particular thing indeed, and in the Netherlands especially. I find there is a certain pride taken in being bold or crass in public; it’s sometimes even encouraged.

Tim: I was talking to Chris Dercon some time back, who was saying how he felt the English were very loud – we got into a whole conversation about kinds of loudness. In the UK for sure there is the loudness of the rich and the loudness of the poor and each has a different place in the city.

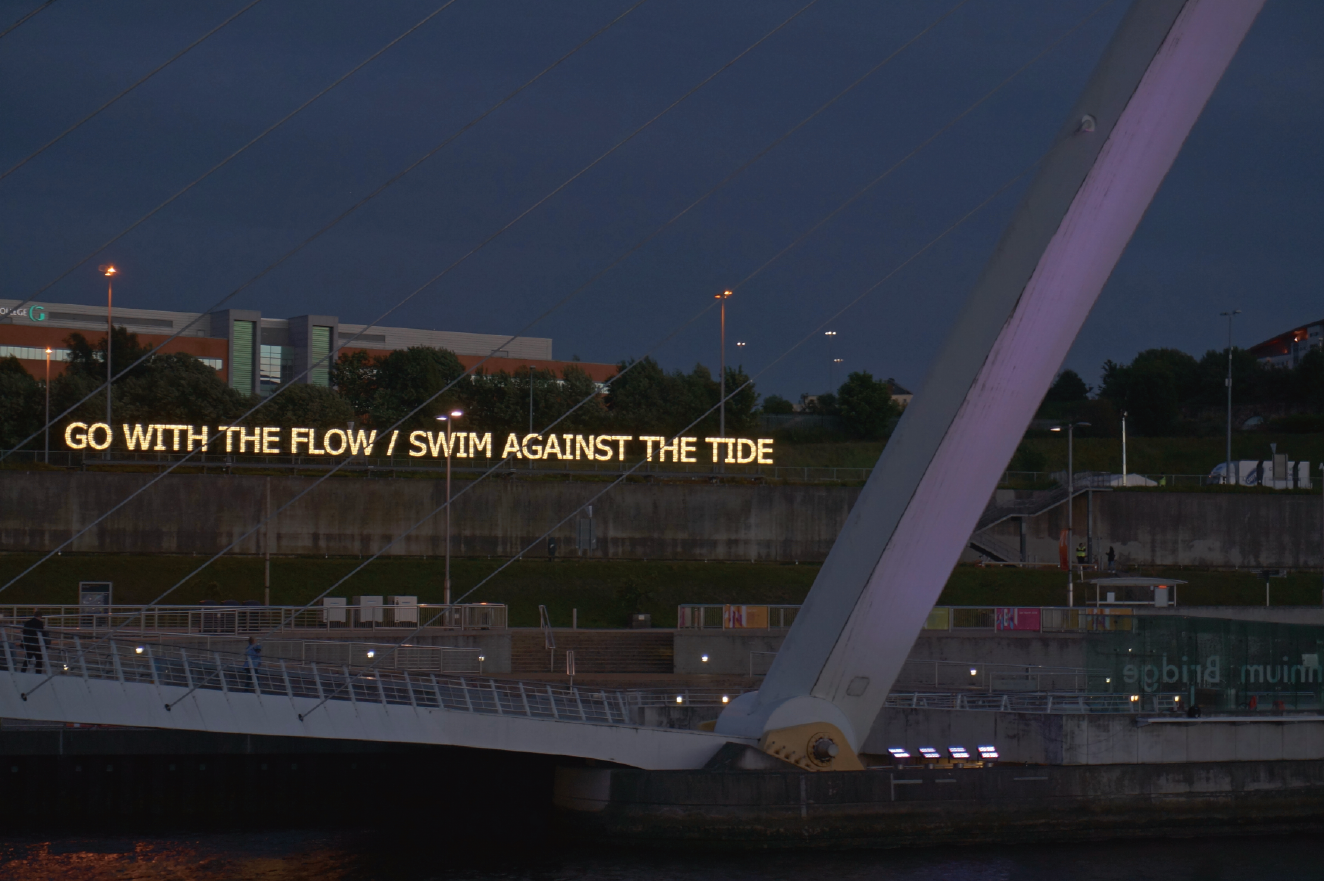

The loudness of the rich is always obnoxious and I never want to be anywhere near it. The loudness of the poor I can feel differently about as it’s so often about claiming and transforming space. Who is allowed to speak, who feels comfortable enough to make noise or speak in other ways? These questions keep me occupied, which is perhaps why the work with language in public space is interesting to me.

Most public space is dominated by advertising, so the loudest voices in the city are somehow always commercial interests. In that context, I’m interested to put language in public space that is not in that particular mode of sales.

Samuel: Another recent work that I’d like to talk about is Of Sound Body (2017), which was part of Witte de With’s recent Kunsthalle for Music project. This work is a performative sound piece where the performer is invited to make any possible sounds using only his or her body. Yet the title also contains that conceptual tickle of ambiguous meaning so typical of your work, when you realize it also means ‘in good health’ or ‘in good shape’. From there I’d like to talk a bit about your thoughts on the relationship between words and bodies, the embodiment of language.

Tim: A lot of my recent solo performances and collaborations have been exploring spoken text in relation to music and the body, starting with my solo A Broadcast/Looping Pieces, leading to an ongoing collaboration with violinist Aisha Orazbayeva as well as a recent project with pianist Marino Formenti.

A key tactic in this work has been taking the kind of language fragments that I might use in a neon, but focusing instead on speaking the words out repeatedly – looping them in performance. The approach is about putting language into time and space, into a body, coming from a body, so that it is not an object or a sign/display, but something rooted in a physicality and a presence. Because, of course, the impact and experience of text changes so much when you do that – it becomes something physical, something embodied, something material. The work with Marino Formenti ended with a nine-hour performance – him more or less continuously playing piano and me more or less continuously speaking, shouting, singing, whispering, a constant working and reworking of language, its musicality, its texture and its semantics and how those things connect to the body.

Samuel: In your works for the theatre, you are putting bodies on stage, on view. As such, these bodies must be pleasant to look at in some way or other, because they enter an intensified space of being seen. I want to ask what attracts you when casting and staging performers. It seems to me you have developed a specific set of aesthetic codes or archetypes throughout the years, and I’d like to see if we could define these a bit. For example, in early works like Nighthawks (1985) or later on Pleasure (1998), there is a Pina Bausch-esque aesthetic present.

Tim: The Forced Entertainment work has been a collaboration with the same core group of performers since 1984 and through that time the five people on stage have grown older. We were in our twenties when we began working together and of course, twenty-year-olds have a certain presence and allure and a particular kind of physicality as bodies. Most of the company now, including myself, are people in their fifties. As bodies change, different things become possible, others become impossible. The journey of the work is, in a way, a negotiation with who we are and what kind of physical and visual presences people present at any given moment.

A lot of the early works have a kind of visual and physical stylization to them, they aspire to a certain cinematic code, they wanted to look beautiful in a certain way. I think we fairly rapidly gave up on that, at least partly because we figured out we couldn’t do it! I think we started to realize we were more a television generation than a cinema one. We were more interested in an aesthetics of sets where things wobbled and looked a bit cheap rather than be in some epic Euro art cinema. The trashiness of a lot of the later work grew from that.

…a way to look at the process of naming – sex, body parts, sex acts – as if the versatility of the body and desire find a competitive force in the versatility of language…

Samuel: Could you talk a bit more about Filthy Words and Phrases, because it seems to me this is the work where you most directly address questions about language and sexuality.

Tim: Both the performance Pleasure and the seven-hour video Filthy Words and Phrases began from a text I’d come across on the Internet in the early nineties. The text claimed to be a list of all the slang words for sexual activities, body parts and so on. It was a disgusting, funny, foul, stupid collection of language – appalling and fascinating at the same time. As we started work on Pleasure Cathy Naden developed a role in which she was writing this list of words – slang terms for penis or vagina or for blowjobs or ass fucking or masturbation and so on – one after another on a blackboard.

During the performance, as other things were happening, Cathy had this habit of looking at the blackboard and then out to the audience, as if to say: ‘what do you think of that?’. She never spoke about what she was doing, but simply kept on presenting these words one after another, as if they were part of some demented language lesson in a very unorthodox school. From that strand of Pleasure we developed the seven-hour long video Filthy Words and Phrases in which Cathy works alone to write out pretty much the entire list on the blackboard, in no particular order, moving between well-known expressions to really ridiculous obscure ones, to contemporary ones of the time.

I suppose the interest lies in the way language proliferates around a problem (sex and sexuality) and the enormous fecundity of language that multiplies around that area of human action. I’m not sure but there’s probably more variety and creativity around language in relation to sex than there is around any other zone of human activity. So the work was an attempt to grapple with that as well as a way to look at the process of naming – sex, body parts, sex acts – as if the versatility of the body and desire find a competitive force in the versatility of language.

Cathy Naden in Filthy Words & Phrases, 1998 Photo: Hugo Glendinning

Samuel: It struck me that Cathy remains voiceless. She writes it all out but she has no agency beyond that. Why was it a woman performing this act? What would be the effect if it had been a man caught in this silent listing of sexual acts? I’m asking, of course, also in light of the recent movements around the position of women in society and relationships of power.

Tim: I think it is very important that it’s a woman doing it. I never felt that Cathy was powerless or trapped. She’s the one choosing and writing the words, saying: look at that, look at this, read this, what do you think about that? It’s more about her as a witness to the vocabulary, someone thinking it through for herself and drawing it to our attention, than about her being trapped.

Of course, it opens the question of who owns all that sexual language, where it comes from and what it’s generally used for. There’s a violence implicit in the language. It’s consistently revolted or appalled by the body, by bodies and what they do. It’s rife with coded and not-so-coded misogyny and homophobia. It’s focused on abjection and objectification; not the body and the sexual act as something ecstatic or transcendent, but as something ridiculous, banal, base, ugly, comical. That’s very much the inheritance of that particular dictionary!

So perhaps what Cathy’s doing is thinking through that language, that relation. In a sense, the person who has no voice is the viewer. If Cathy were speaking, it would be her problem. But the way the material is presented, as in a lot of my work and the work with Forced Entertainment, is that the problem remains with the viewer – Cathy presents the words; we’re left with the job of thinking about them.

Samuel: I’m thinking of another work relating to the potential violence of words and the tension between attraction or seduction and violence or threat: your reworked version of Bruce Nauman’s Violent Incident (1986). When did you first see this work? You were already making work yourself in the year it was made.

Tim: I don’t remember exactly when but it wouldn’t have been as early as 1986, but certainly a long time before I made my version of it in 2013.

Samuel: What prompted you to revisit that work? The original version is a multi-channel video work, shown on a grid of monitors, playing multiple takes of the same material in different variations.

Tim: Yes, it presents a slapstick routine between a man and a woman at a dinner table. The man offers to pull back the chair for the woman but pulls it too far so the woman falls over, then she sticks her finger up his ass, then he throws a glass of water in her face, and so on. I made my work for an exhibition about versions and originality… so I was already thinking about repetition in that work and the difference between performance repetition and filmed repetition. I was interested in the fact that Nauman made the work in multiple takes and I wanted to see what happened if I just made it a loop, performed as a loop. So, my re-take is an un-edited hour-long video where the performers endlessly do the same choreography. In Nauman’s work, you are aware that the work is made from different takes whereas in mine the same choreography, the violence of it, takes on a different aspect. In the beginning, you are very aware of the actors performing and playing this routine but then over the hour they get wetter and wetter and more and more tired, and uglier. There’s an ugliness about the violence between the two of them that intensifies over the hour.

Samuel: And yet it’s precisely this ugliness that we find captivating or intriguing. Allow me to ask a general but also poignant question: are there any artworks or forms of art you find particularly attractive, seductive, sexy? What are you drawn to in a sensuous manner, rather than a conceptual manner?

Tim: I’m not sure how far I’d go linking my attraction, interest or fascination with artworks to sexual attraction! In terms of artworks I think what really attracts me and holds me is a certain kind of confusion or complexity. An object, a text or an event that has layers or contradictions, something that confuses me. I find the confusion enthralling or captivating. Things that have a single, very clear visual pleasure don’t tend to really get me. Things pull me into process or contradiction. I can love someone like Cy Twombly for example, because of the huge complexity of the work – the sense the drawings have of time and effort and the person. I can find that really enthralling.

Samuel: It’s not about the full-frontal uppercut effect then. It also relates to what you were saying about the missing or hidden part a viewer always has to add on their own. The concealed, not the revealed.

Tim: There needs to be a space to get implicated personally. The intimacy of performance is something we know and understand, but I think objects and images also produce their own kind of intimacy, a kind of complex relation, the same way that texts do.

Samuel: What about voices? You have made many pieces using recorded voices. For the recent work in Leeuwarden, did you go looking for specific voices? It’s such a tricky thing for artists to use voices; all too often people think: I have a voice so I’ll just record it myself. But there’s an art to knowing how to talk for a recording properly. Think of perfume or car advertisements and those specific urgent and sexy voices they use.Tim: We collected the voices of about forty or fifty people based on who we knew that spoke other languages. They weren’t originally gathered based on the quality of the voice, but the piece does make use of the diversity of all these different voices, different energies, from the deep gravelly voice to the child who’s struggling to remember the alphabet. It’s amazing how intimately present these people become from the recordings. There’s a great book by Steven Connor about ventriloquism called Dumbstruck. I remember this particular passage where Connor talks about the way a voice that doesn’t have a body is unsettling because it always summons a body, makes us imagine a body. He talks about the era when they were first recording people like Frank Sinatra, and how they would put the microphone very close to the mouth so you’d get this uncanny sense of a person who is really close to you, whispering in your ear. I am thinking a lot about these things, how sound conjures body – it’s very present in my installation in Braunschweig from last year called Together/Apart. It was made over fifteen speakers through the whole space of the gallery, using recordings of my voice. I’m working with idiomatic phrases related to the body, especially phrases that (when taken literally) create contradictory or impossible images of body – ‘Keep Your Ears To the Ground’, ‘Watch Your Back’, ‘Laugh Your Head Off’ and ‘Cry Your Eyes Out’.

This is perhaps slightly off topic but I’m remembering a great text by the writer Roseanne Stone, who in the 1990s was writing about virtual reality and tech-based virtual communities. One example she gave was phone sex. She talked about phone sex as the process of the speaker passing words down the phone and the listener constructing bodies at the other end. I find that an amazingly useful description of how language works: the very reduced or compacted form of spoken language as sound being unpacked into bodies via someone’s imagination. I find this idea of unpacking language very important in the work.

Samuel: The descriptive text for Filthy Words and Phrases says the performance shows the ‘hard work of language’. I’m sure phone sex is hard work.

Can we talk about your collaboration with choreographer Meg Stuart? In some of her work she has explored the ambiguities of the sensuous body, and in your collaborative performances, you share the stage with her.

Tim: One of the places I connect strongly with Meg is that as a dancer, she embodies the idea of the human body as a meeting point for many other bodies, for possible or imaginary bodies, for alternative versions. When she dances she often talks about it in terms of channelling certain images or narratives, possibilities passing through her as she dances. The body is a very porous, fluid space for her and when you watch Meg you really see that. She has this capacity to shapeshift and be between many identities as a physical presence. My work with language strongly relates to that. I talk a lot, as a speaker, about being a site or a switching station through which many other voices are moving. In a sense, identity, who and what one is, flows and reconfigures according to language. Because when we speak, we’re always speaking to other people. All of these words we are speaking have been used before. We can’t speak without quoting or shadowing other people, like parents, lovers, friends or teachers.

Samuel: You could say that is also a form of ventriloquism. We incorporate the people we are inspired by and give voice to their words and thoughts anew.

Tim: Yes, exactly that. The big connection for me with Meg is the idea of the voice and body as these sorts of unstable meeting points, of possibility and friction between realities, fantasies, versions.

I want to go back to the question about what it is to work with performers and to think about how one wants to watch other people. In a lot of the Forced Entertainment works, the emphasis is on people who are comfortable in their skins. There’s something about looking in, at people busy with something, like watching musicians play.

Samuel: It’s interesting you mention being comfortable in your own skin because there was a moment in your practice when almost every piece had a performer wearing an animal suit. What is that about? I can’t help but think of furries, and of objectification.

Tim: There is a real interest in my work in the business of dressing up, of transforming, of becoming another creature, not a human animal but another kind of animal. There’s also a really interesting thing that happens when those animal costumes get taken off, which is perhaps the main reason they are there. In Showtime (1996), Cathy again, for most of the show, plays a dog – wearing this ridiculous dog’s head costume, barking, running around on her hands and knees. At some point in the performance she takes off the suit and you see her face and she and Claire Marshall, another Forced Entertainment performer, have a conversation on microphone. At that moment, suddenly revealed, Cathy is so present, you feel her, and her humanness and vulnerability in a way you really wouldn’t if she had just walked onto the stage. It’s about hiding and denying, being transformed, covered, and then this moment of revelation of a human being. It’s very simple but also very strong. To me that’s always one of the key moments in theatre, when you cut the theatricality and people are present in a very different way. Like when you watch actors just before they go on or come off stage, there’s something about actors in those moments. That’s interesting to me, finding ways to try and capture that reveal. That’s why I often make long performances or work with improvisation – looking for a way to get away from what’s deliberately shown or told, to gain access to what’s underneath, to what’s unconsciously revealed, what’s present in a way that’s at once both more banal and more rare.