What will love look like in the future? Croatian philosopher Srećko Horvat expects a radical change in our most intimate mode of life. He advocates not to be afraid of the fall once you fall in love. Srećko is described as ‘one of the most exciting voices of his generation’. He is the author of several books, among them ‘What Does Europe Want?’ from 2013, with Slavoj Zizek, and his articles are regularly featured in major outlets such as the ‘Guardian’ and ‘The New York Times’, while his work has been translated into more than fifteen languages. In his latest book ‘The Radicality of Love’, Horvat considers our twenty-first century a narcissistic age in which love is missing and sex is hyper-inflated, due to new technologies of the self (Grindr, Tinder and other online dating platforms). He explores what would happen if we could stroll through the revolutionary history of the twentieth century and asks some of their protagonists seemingly naïve questions about love. In our conversation, love becomes the main elevation of our thoughts on the mundane.

Srećko Horvat

Dimitris Dalakoglou: I remember Rudyard Kipling’s The Finest Story of the World, where the young Charlie Mears, who is the best author in the world –according to his mentor – and is working on the world’s best novel. Eventually Charlie falls in love so everything, all his energy, is wasted and the novel is never written. This is a typical motif appearing among activist and revolutionary circles where you notice a critical judgement put on love and sexual relationships. So, I wonder if revolution and love are mutually counterproductive?

Srećko Horvat: I really like your first question and the Kipling story but I’ll attempt to turn it around. You know sometimes it can just be the opposite. Falling in love and great romantic relationships in the end can serve to create better art. Be it a novel, a movie, a painting or something else. I think it still holds true what Hegel said about Thucydides – that the Peloponnesian War happened just so Thucydides could write a book about it. Even great love romances only happen so artists or writers can make a great artwork out of them.

We possibly need a dialectic between the ‘falling in love’ and ‘art’; the same goes for revolution. What I’m trying to do in my book on The Radicality of Love is to show that there has always been a deep connection between revolution on the one hand and love on the other; in the sense that all great revolutions take on the question of the personal, the private and the intimate sphere. The best expression of this nexus is when revolutions turn into totalitarian systems. For instance, in The Radicality of Love, I am writing about the Iranian Revolution or about Stalin after the October Revolution. Even when you read dystopian novels by George Orwell or Zamyatin, you will see the totalitarian systems always rely on the ‘privatisation of hearts’.

The totalitarian system always has to deal with desire, not only to suppress it but to canalize and foremost create desire. You can notice this properly in revolutions that start with a huge longing/yearning for emancipation, equality and radical change. Then occasionally, actually very often, it develops in a wrong direction. The October Revolution ended up with a suppression of desire. It started in October 1917 and in December of this very same year Alexandra Kollontai implemented the most radical laws permitting homosexuality, for instance, and in 1933 Stalin prohibited homosexuality again.

On the other hand, you have the revolution of May ’68 that started with this great desire for so-called ‘free love’ and polyamory. Unfortunately it ended up in this kind of capitalist consumerist dystopia where love and sex became just another product on the market.

Dimitris: This is a very interesting point. A lot of the anarchist pamphlets and propagandistic materials in history were smuggled together with pornography across borders. That’s part of this intimate revolutionary history.

Srećko: One of the biggest revolutions in human history – the French Revolution – proves exactly this. Not many people are aware that modern pornography has its origin in the French Revolution and that precisely the pamphlets, which were pornographic, helped overthrow the ‘Ancien Régime’. Writers such as Mirabeau or Saint-Just had all been pornography writers before becoming the leaders of the French Revolution. The most common pornographic character in these brochures was Marie-Antoinette.

With more imagination we would not only be able to create different relationships that would be outside of the leading paradigm, but we would also be able to create different sexual experiences.

Dimitris: Why would they choose Marie Antoinette?

Srećko: As Marie Antoinette was the symbol of the nation and the symbol of royalty. Therefore she was a symbol of power. If you attack her body, if you do something with her body, this is where pornography comes in, you’re actually subverting power.

This explains why the brochures with Marie Antoinette were the most popular brochures during the French Revolution and to some degree even led to the French Revolution. So you can see with the French Revolution that it first started with this huge emancipatory potential when pornography still was subversive, and then in the years after already, pornography became something very common.

If you follow the development of pornography – I would call it a regression in pornography from the French Revolution to today’s times – you see that there is a kind of regression again from a very emancipatory art or practice to something which becomes part of our consumerist culture. I am not only talking about the fact that pornography is a male practice. Neither am I talking about the exploitation of women which, of course, still is a problem. What people are not talking about from a philosophical perspective or even an anthropological one, is something in porn called categories. When you come to a porn site you usually have thirty to forty different categories such as ‘threesome’, ‘teen’, ‘anal’ or whatever you like. The problem is that although you seem to have so many choices in the end it actually narrows your imagination.

If you speak to people you will get a really interesting insight into their personality type. Sometimes I ask friends as a kind of unscientific research, ‘Okay, when you masturbate, what kind of categories do you search?’. What I have found out is that women do masturbate using their imagination more than pornography. This is something that we should rehabilitate. When I ask some male friends, ‘Okay, why do you masturbate on these particular three categories?’ most of them say, ‘I don’t have time to do it without pornography, so I search for a category, I have five or ten minutes, I do it and then return to my everyday practice.’

The problem today is that precisely imagination is disappearing as you need time to have imagination. With more imagination we would not only be able to create different relationships that would be outside of the leading paradigm, but we would also be able to create different sexual experiences.

Dimitris: Your approach to online pornography is rather critical, locating it within a spectrum of a wider critique of capitalism where you see these endless choices, as a libidinal economy. Sex is also a profitable industry although it involves all forms of workers’ exploitation that already exist within the labour market. There are also sex workers making a living from the enormous increase that the internet brought about. We are facing a challenge of the market by amateur online pornography that is allowed via the internet.

I agree with this critical viewpoint on the consumption of pornography and its role in the male imagination and people’s sex lives. It is empirically observed in social sciences that generations who grew up with the internet and online pornography have very different sexual behaviour than other generations, which sometimes scares the experts as they consider it as something unusual.

Does this critique partly echo a familiar fear for alternative views of body politics?

Srećko: It must have been one or two years ago when I was invited to speak at an academic conference at Birkbeck University in London; there was this girl in the audience approaching me and other speakers for a drink. During a cocktail after the conference she said, ‘Do you all want us to go to my place later?’ There were about twenty of us, men and women, having drinks and someone was playing the guitar. And at that point I asked, ‘So what do you do?’ and she said, ‘I’m doing a PhD in social sciences and besides that, in order to finance my PhD and studies, I’m a sex worker.’

Asking further, ‘How do you conceptualize this? Do you find you are being exploited? What about the labour rights, etc.?’ You know what she said, and this is wonderful, she said, ‘I like sex so it’s good that I can be paid for it.’ So, if you can really reach this level of being satisfied both with your work and how much you get paid, it’s wonderful, but I’m afraid this is not valid/does not apply for most sex workers nor in the general labour market.

For instance, we have everyday news from Boko Haram rape camps where you have victims as young as eight years old, and also with the refugee crisis, some of the children go for slave labour and sexual labour. What you’re describing is actually, yes, we have to accept that this labour market does exist and with certain labour rights it can be regulated. This would be my basic answer. I also like the more philosophical approach that my good friend and philosopher Laurent de Sutter developed in his book The Metaphysics of the Whore.

Laurent’s main thesis is that the prostitute has a key to the truth. The prostitute is the point where all the truths of the society intervene and it is called ‘libidinal economy’. You have everything in the figure of the prostitute. The prostitute is a very subversive character. Sex today and desire still can be subversive; we just have to re-invent it.

The problem is, and you can see this in Amsterdam when you walk through the Red Light District. For me, there is nothing sexual any more in the windows where prostitutes are waving you in. I’m not even opposing it from this labour perspective as they probably do have more rights than other sex workers in different parts of the world, but from the perspective of imagination it’s not subversive any more. This is the problem with consumerist culture – sex has become commodified.

An even bigger problem is that actual love, and there is a difference between love and sex, became commodified as well. Love also appears as just another interchangeable product in the market, so if you cannot find someone, there will be somebody else.

Dimitris: In anthropology there is the theory of the gift, as it is beautifully described by the French sociologist Marcel Mauss. According to Mauss, every single type of exchange, including our very modern contemporary capitalist monetary exchanges, involves and engages a gift economy. Even within the most commodified version or what looks like the purest version of economy where the ‘laws’ of demand and supply govern, for example, think of stock markets that still depend on an economy of favours, information or on an economy of various other types of non-monetary exchanges.

Debt is something that makes the economy function while in principle it is a type of gift. It’s one person giving something to another person without expecting a direct payback. Do you think all types of relationships, even love and sex, are based on this kind of exchange?

Srećko: Not necessarily. Just think of Georges Bataille who speaks of the ‘accursed share’, this excessive and non-recuperable part of any economy which must be spent without thinking about gain, for instance, in non-procreative sex. This notion of ‘excess’ is crucial for Bataille.

When you are encountering this excessive energy, the radicality of love or even the radicality of sex, then you know it is something which cannot be exchanged any more. It’s not only Georges Bataille; in Malawi, for instance, you have an entire culture which is called Nyau. Nyau is also the name of their philosophy. Within this kind of philosophy, before Bataille, the Nyau believe there always is – and should be – something which cannot be accountable or exchanged in these classical economical terms. An interesting artist from Malawi called Samson Kambalu is dealing with this.

To put it straightforwardly, when you give something to someone, it is only truly radical if you are giving without expecting anything in return – when it is a gift without creating a debt. Because by doing this you are actually subverting the predominant paradigm which is the ‘economy of indebted men’. This has been best described by Nietzsche who pointed out that the etymology of ‘debt’ in German language comes from ‘Schuld’, which at the same time means ‘guilt’ and ‘debt’.

People who are indebted today, for instance in Greece, are ‘guilty’ at the same time because they are indebted and it’s not the International Monetary Fund that is – together with European financial institutions and private banks – actually really guilty for their indebtedness. The interesting point here about Nietzsche is that he puts this in relation to temporality. You give me money and I promise to pay you back.

When the promise is created as a practice then a temporality is created. By making a pledge that in the future I will return the gift, the human society already started to think in terms of further development and future acts and what they will do. The problem today is that we reached a level which has been described by Franz Kafka in In the Penal Colony. In that piece people who have committed certain crimes would get their sins tattooed in their skin and can never get rid of them, literally.

To my opinion, we are living in such a penal colony, everyone who’s indebted today – be it a loan to repay your apartment for the next thirty years, be it a loan to repay your PhD for the next ten years or be it just your American Express or MasterCard – everyone who is into this kind of economy is already part of a kind of libidinal economy and is living in a penal colony I would say. When you are indebted, all your future acts – including emotions – are actually governed and influenced by the very beginning of this indebtedness.

More and more people got to perceiving love as a kind of investment; we invest in something in order to gain something else. If the other person does not seem the perfect commodity then you don’t invest because you won’t gain anything in return. Again we are coming back to ‘libidinal economy’.

Will I give this interview? No, I won’t agree to this interview as I don’t have time. I don’t have time because I have to do something where I will earn money and I have to earn money to repay the debt. Thank God I don’t have any kind of debt at all so I don’t have these problems. I think we can really speak about a different kind of psychology or moreover another mode of existence today. And the problem is that this way of functioning also transfers itself onto the most intimate sphere.

Dimitris: I’d like to direct our conversation to another topic. Recently Cologne has become the centre of a big debate on the refugee crisis for which the supposed massive sexual harassment of women by refugees on New Year’s Eve has been the excuse.

It is interesting to see how critical arguments are coming to a halt when encountering real experiences. Even if you have an elaborate antiracist argumentation to engage in a dialogue it just hits the wall when someone tells you, ‘yes, that’s me who had my private parts grabbed without my consent’.

Srećko: Since I’m in Cologne at this very moment, first of all, politicians and citizens should face the molestations that happened in Cologne. Some harassments really happened and, yes, we cannot continue this game of completely fetishizing the refugees in the sense that they could even be the new revolutionary subject, as some leftists tend to believe. On the other hand, some go so far as to say that refugees cannot be bad. How can people who fled from warzones be bad?

A basic fact is that we’re all human beings so as human beings you have good and you have bad people. The problem with Cologne is that, as the statistics are showing now, most of the perpetrators were not refugees. They were immigrants, living in Cologne for quite some time, and there were not so many crimes as recorded at the very beginning, it was really a kind of carnival. This doesn’t mean that some crimes didn’t occur, I’m not saying this.

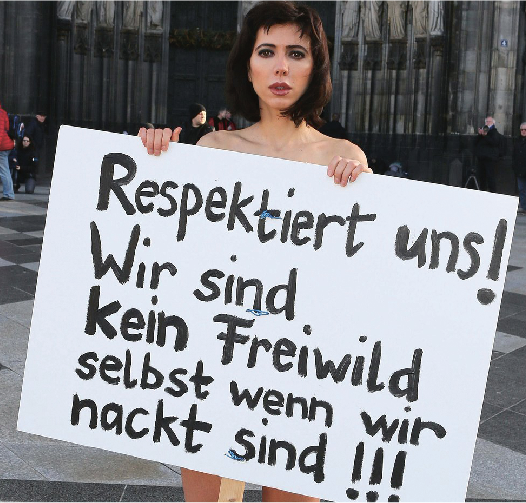

‘Respect Us! We are not fair game even when naked!!!’ read a simply painted protest sign created by Milo Moire on Friday. The Swiss artist wore the sign and little else during her performance in front of the Cologne Cathedral on Friday, which was a nude protest against sexual assault in the city.

When speaking about Cologne it’s important to talk about a tendency that you have in the West today, especially after the Paris attacks and now after Brussels. On the one hand it is a ‘state of emergency’ and on the other hand it’s what the Germans call ‘Denkverbot’, a prohibition to think. We are going back to the worst dark ages of political correctness where you cannot say that after Paris or Brussels our cities became war zones. When I was recently stopping over in Brussels for Cologne, I almost missed my train to Cologne because the airport looked like a fucking war zone. You have soldiers every five metres.

Now, of course, you could argue – isn’t this just a reaction to the terrorist atrocities that happened? I’m not saying the attacks didn’t occur, I’m not playing this game, not condemning terrorist acts; they happened in Paris and it’s terrible. They took place in Brussels and it’s horrible. What I’m trying to say is that we should really be warned when our cities turn into a kind of terrain of a civil war. I was born and raised in Yugoslavia and lived there during the war. I know how it looks like when the army is in the streets all the time.

If you lose the difference between police and the army, you can only conclude that we are experiencing a civil war. I think we live in dangerous cynical times if the blame is laid upon the refugees. And the cynicism can also be found in the pure numbers.

…This is why it gets more important than ever before to speak about love,..

Dimitris: It’s interesting that we tend to attribute these attacks to events that happened out there, whilst the actual perpetrators of these attacks are very European subjects, people who were born and raised here. In fact they are some of the best examples of a neoliberal nihilistic subject. Although the Belgian government refused it, the Minister of Migration did propose allegedly to the Greek Minister of Migration to let refugees get drawn, what kind of subjects will such polities produce?

We’re almost told not to care for 5,000 people who died at the European borders because the frontier eventually is much more important than human life which is a completely nihilistic logic. Of course I think there is another problem within the neoliberal social class configurations. You see how exactly it works in Europe. If you’re a refugee or you have a migratory background then you have very few chances to get a well-paid job, there’s less chance of finishing university and so on. However, the hegemonic discourse is that we don’t have any class conflict any more.

If there is no class inequality, struc-tural violence or exploitive labour relationships are to blame for inequality. Eventually, since we are seeing a strong de-politicization in Europe, there is rarely any political analysis of what happens to us.

Srećko: Today we have a final realization of the classical Margaret Thatcher-motto, ‘there is no such thing as society, only individuals’.

What does it mean? It means that it’s not the society any more, the healthcare system, the social security or educational system, everything which has been functioning to some degree in the so-called ‘welfare state’. Now it’s not society or the state any more that is responsible if you don’t have a job, if you don’t have education or if you have serious health problems. It is you who’s responsible if you don’t have a job, if you aren’t educated properly or if you’re sick. This is the kind of new ideology the philosopher Maurizio Lazzarato calls the ideology of the self-entrepreneur – everyone becomes a businessman.

What I’m trying to show is that this kind of ideology even goes one step further. It’s not only on the level of finding paid work or education or good healthcare that we are all responsible for. It’s not a failure of the system, no, it’s not a failure of the multimillionaires, tax evaders: it’s our own failure.

I think what is even more worrying is that this paradigm penetrated into the most intimate sphere so that it’s also our failure if we cannot find an appropriate partner. This is why in late capitalism it gets more important than ever before to speak about love, and to try to understand the specific relationship between capitalism and love.