Celebrated for her groundbreaking work in Black feminist theory and queer studies, Alexis Pauline Gumbs continues to inspire many as we forge paths of mutual care and restorative justice. Gumbs has been an important figure for me and provided crucial insights for my now-defiled Istanbul Biennale proposal. Her book Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals (2020) sheds light on the resilience, adaptability and interconnectedness inherent in both marine ecosystems and Black feminist praxis. Influenced by the quantum presence of poet Audre Lorde, our conversation delved into topics such as self-transformation, love and pleasure, the foundational role of ailment, survival and cure in revolutionary activism, and the communal bonds Gumbs forged between her ancestral Anguilla and her beloved Durham in North Carolina – her spiritual and physical homes, respectively. I transcribed our one-hour interview in Ishigaki, Okinawa, delving into her cosmic tales around her ‘aspirational cousins in the oceans’ to broader political themes.

Defne Ayas: Foucault once said, ‘The object of my work is my own transformation.’ How much did the marine presence shape you and inform your self-transformation?

Alexis Pauline Gumbs: There is this foundational marine presence – the embryonic experience of being in a sense a marine mammal in the very small ocean of the uterus and growing from that point. I’m part of a Caribbean family; I was raised by people who believed that there is an inherent marineness to us, a ‘throw her in the water and she’ll remember how to swim’ type of approach, which was very formative for me. My grandfather was a person who spent a lot of time in the ocean, and so did I from a young age.

I was also terrified of all the unknowable things that could happen in the ocean. The vastness of the ocean holds a salience for me; it changes you. It requires you to be open in a different way, to trust in a different way. I remember holding on to my mom, my grandfather, my father, my grandmother. I could be in the ocean, but I needed to hold on to them. In my grief, after my father died, I found myself drawn back to the ocean in my writing. There was an impulse to return and immerse myself. I think this is because the marine presence is so linked to what it means not just to love people but to need them. It was never more clear to me how crucial other people were to my survival than when I was in the ocean, feeling vulnerable in its vastness. I needed my family members to hold on to, or at least to be within a certain distance, to feel like I could be there and be OK.

In our family there’s a sacred bond with the sea. The tradition is that we go to the ocean to have conversations. Conversation flows in its waters; it is our shared sanctuary, a supportive space.

When my father passed, I sought and found solace in the ocean. I was crying every day and struggling to breathe, feeling immense grief. An ocean of tears. And so I turned to marine mammals. The ones who know how to deal with the liability of lungs in the depths of the ocean. I needed to apprentice myself to their grace. To open myself up.

The death of my grandmother, who I also write about in Undrowned, was also a pivotal moment. She designed the Anguillian flag with its three dolphins, symbolising her profound affinity to the marine world. She was the first person I loved to pass away, and despite her death, I needed to continue listening to her. I had to keep our conversation going. That’s what is at stake in my practice and what my creativity aims to achieve: keeping those portals open and finding the ceremonies for listening across everything, oceans, death and our own fear. Her death, and death itself, has transformed me. As it must. My creative commitment is to stay true to that ongoing transformative impact. I will never be the same, and my grief has been a major guide. Those edges, life and death and love, ocean and earth and sky, define my relationship with this planet. Maybe this body is an interface where edges meet up.

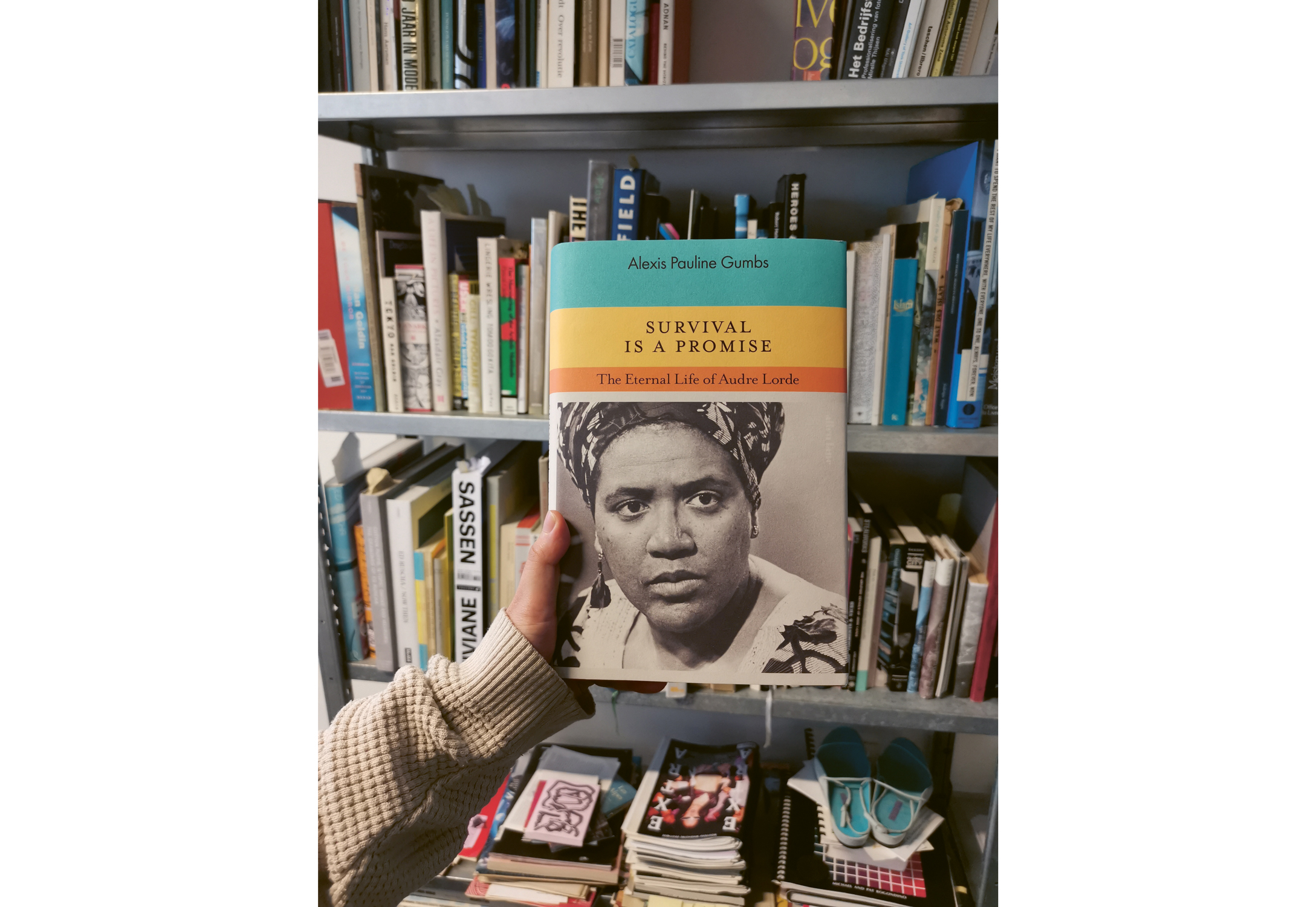

Courtesy of Titan Books. Photo: Sufia Ikbal Doucet

Defne: How and when did you decide to integrate this oceanic depth into your creative process as a writer, poet, warrior and healer?

Alexis: I must have been around seven when I first started writing poetry about my family members. And unicorns. To me, my family members were at once mythically impossible to describe beings and my everyday reality. That’s still what I do, but my understanding of the expansiveness of family has shifted. It has grown.

Defne: It seems the more you listen, the stronger the ancestors seem to come through. Your writing creates a resonance in all your readers, stirring something deep within.

Alexis: The door is open, and so much comes through. I am committed to keeping myself clear so it can keep coming through. Even the water I’m drinking is a part of tending the throughway. The meditating and the sleeping and what am I tuning into and noticing where I am blocked. All of it is a practice of seeking to open more to the infinite love coming through. Some of the most important work and learning are about those blocks and what they have to teach me. I have to be with that, in the process of self-transformation.

Defne: We’re all in this human experience, and sometimes we come off the saddle and need to get back on it. What does it take to connect back?

Alexis: I would say breath is one. For me, it is the primary way to come back. I had a wonderful high-school English teacher, Catherine Tipton. She taught me this breathing exercise. You sit on your hands, breathe in for four counts, hold for four, and breathe out for four. It’s a very simple exercise that was incredibly helpful to me at that time, and it continues to come back to me. I offer it to my own collaborators now in moments of overwhelm. The concept that resonated with me is how regulating my breath can regulate so much more, including my nervous system. It brings me back into the flow of inspiration, allowing me to be present. It helps me return to a scale where I can be intentional. That’s one of the ways I ground myself.

Sometimes, for me, it’s also about sitting on the ground. As a Gemini, with most of my planets in air and some in water, I find it necessary to connect with the earth. Literally. I put my forehead on the ground. There is only one planet in my chart that is in an earth sign, and it’s Venus, my love. This makes sense because in many ways my relationships are my ground, my earth, my only stability.

…What I know is that love is not limited by anything, and it flows through everything. So, in my process of listening and engaging in ceremony…

Defne: Where does imagination play a role in all this?

Alexis: I’m not sure if it’s imagination or an acknowledgement of spiritual truth. What I know is that love is not limited by anything, and it flows through everything. So, in my process of listening and engaging in ceremony, I know that I can engage with any being living or dead, or of any species or existing in any possible or seemingly impossible quantum version of reality. The creativity comes from finding the ceremony to actualise that possible connection across the supposed divides of time, space, life, death, species, geography and language. I’m not imagining that, though. I’m just pushing aside everything that obscures that reality of infinite presence. I’m activating whatever ceremony is needed so I can tap into what is real in terms that I can access and maybe that other people can access when it shows up in my writing. In Undrowned I didn’t imagine that we were connected to marine mammals. We are connected. I was just finding a ceremony for us to access that in an even more intimate and visceral way.

Defne: What is your ideal sort of environment on this planet for your spiritual and intellectual nourishment?

Alexis: Anguilla, where much of my family is from, is a place I feel the need to visit regularly. It holds a depth and standard of spiritual listening that teaches me how to listen deeply everywhere else. However, my home, for my adult life, is Durham, North Carolina. Durham is a pretty incredible city with a rich Black and Indigenous history and a lot of trees, and I find their rootedness very calming and grounding. The trees and the people. My community here is rooted, expansive and interconnected like the trees, and their visionary way of organising grounds my practice. The scale of impact is almost like a small island. We all impact each other.

Defne: You are not leaving it anytime soon it seems. All your beautiful work is coming from Durham.

Alexis: Nope! I’ve been living here for twenty years and I’m staying. My first visit here was during the summer when I was a kid. I took an African American history course taught by Dr Charles McKinney as part of a youth enrichment programme (read nerd camp). We learned about the rich history of this city, particularly its Black history. It resonated with me deeply, even as an eleven-year-old, and I believe I was meant to live here as an adult.

The sit-in movement for instance (the non-violent movement of the US civil rights era) began nearby in Greensboro in 1960. There was also an earlier sit-in, the Royal Ice Cream Sit-In, in Durham, so this is part of the foundation of the city I am living in.

Defne: Revolutionary Mothering: Love on the Front Lines (2016) talks about spiritual and communal ways of bonding across generations in Durham. Where do you locate the sensuality? What do the night and day look like in Durham?

Alexis: The mother of this community is the Eno River, stewarded for centuries by the Saponi relatives. The sensuality and flow of the Eno River and the nearby Haw River are part of my experience of this area, and my community immerses in, sings to, and does ritual and reflection at the river often. My partner and I made a film where the main character is the river. And as I said, there are the trees. I hear the trees, and there are lots of indigenous trees, but there’s also a lot of plantation pine, due to the lumber industry. This reflects settler logic and subjectivities. Sweet gum trees and magnolia trees shape the day and night too of course. Pre-colonially, this area was plains with buffaloes roaming, an actual prairie. A major part of the sense of Durham for me is the smell of tobacco. The Saponi people created incredible tobacco medicine, cultivating heirloom tobacco for many generations. So breathing in Durham is freshwater inflow, our interlocking fingers and dreams, the scent of the ceremony.

Defne: Tobacco as the spiritual medicine?

Alexis: Exactly, a sacred tobacco. The colonial tobacco industry came to this area, and it became the primary cash crop. You can still see tobacco drying sheds around. Many of the downtown buildings were once tobacco-processing spaces. Now of course they are trendy lofts.

One interesting aspect is how tobacco, originally used as medicine, evolved into the cigarette industry and became associated with cancer and addictive consumption. This history is part of the reason why Durham is called the ‘City of Medicine’ and why the Duke hospital system and cancer treatment centres are prominent here. This place has a medicinal essence, but it has been thwarted by settler colonialism, extractive logic and addictive capitalism, turning something potentially healing into something toxic. Yet, it’s interesting because the people here seem to have a medicinal purpose, even if they are not in the medical field. There’s a sense of healing here – a place where many healers have been or are currently. For instance, I think about Cara Page, who coined the term ‘healing justice.’ Where did she live right before she created that term? Durham, NC. She has since moved elsewhere, but the impact remains.

Defne: It sounds like there is a capitalist core that Audre Lorde would want to undo. Having a sneak preview of your upcoming biography of hers, Survival Is a Promise (2024), it sounds like her influence began early in your life and has grown steadily ever since. Tell more about the medicine Lorde’s work is.

Alexis: I think of Lorde as quantum, partly because of how she perceived her life and all life. In one interview, she describes life as a fund of energy – our life force comes out of it and goes back into it when we die. Also, I am guided by her science fiction perspective, and her thoughts on the construction of the atomic bomb significantly shaped her worldview.

Lorde’s presence in my life isn’t a coincidence. It’s persistent. I first learned about her when I was fourteen, in a feminist bookstore, as part of a young women’s writers’ group. We weren’t necessarily writing about Lorde, but her books were there. Someone at the nearby college was teaching them, and they were stacked up in the room where we met.

Lines from her poems became epigraphs for all the papers I had to write in high school and much of college. Sometimes it was just a phrase, a particular line or a stanza. I didn’t always understand the meaning of the whole poem, but I didn’t need to. I needed the medicine that was there.

I’ve tried to replicate that in the ways I create oracles from Lorde’s poetry. We alphabetise it, ask a question, and read only the words in the poem that start with that letter. The medicine comes through, in a concentrated and potent way.

Defne: In The Erotic as Power (1978), Lorde defined the erotic as ‘a resource within each of us that lies in a deeply female and spiritual plane, firmly rooted in the power of our unexpressed or unrecognized feeling.’ She also went out to evoke potent goddesses and spirits from the pantheon of West African divinities.

Alexis: The first thing Lorde wrote in her journal after her cancer diagnosis was that she wanted to return to Africa. And in her home along with her altar, which had items from her earlier trips to West Africa, she displayed images of African women who she saw herself in. She wrote The Black Unicorn (1978) to really map the contours of her desire for inclusion in African cosmology and also her specificity and difference as an African woman born and raised in the Western world. Her poem ‘125th Street and Abomey’ is a beautiful example of that. It is a sensual work, from hair braiding to time-travelling oral sex; it is a beautiful work. Lorde’s research on West African relationships, mythologies and stories was also part of her challenge to binary ideas of gender. She was interested in queens with husbands, collective households, parenting models and especially warrior women who modified their bodies to become better fighters. She identified that as part of her lineage. It became part of the way she understood her mastectomy. You’ll remember that she wrote erotically about the mastectomy scar of one of her mentors/lovers, Eudora in her biomythography Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982), and then in The Cancer Journals (1980) she writes about her refusal to hide her mastectomy, the sexiness she finds in dressing to accentuate her asymmetry, like the warrior women who cut off one breast to become the best archers in the world. I believe that Lorde’s work on African gender diversity and embodiment is part of the foundation of the gender-expansive Blackness of my lifetime.

Defne: And there’s her definition of the erotic ‘as an assertion of the lifeforce of women,’ and her mandate that as women we need to examine the ways ‘in which our world can be truly different.’

Alexis: She was critical of a patriarchal engendering of the world. She strongly believed in a divine feminine that could be honoured and lived in all people. She also felt that the depth, darkness and transformative vulnerability of that possibility required honouring that feminine energy. Not repressing it, as patriarchy must in order to reproduce a status quo. So yes, it is Indigenous women who need to be our leaders and teachers in how we redeem our collective relationship to a planet, but not simply because of how we identify or even how we have been marginalised, but because we need a liveable world that is not afraid of the dark, the unknowable, the deep inside of transformation. I think Lorde’s example calls on the feminine energy in all of us.

What Lorde offers is a powerful definition of survival. It’s a definition that centres on the creative power of difference. This resonates deeply, especially as more and more groups face destruction and eradication. ‘We were never meant to survive,’ Lorde reminds us. It would be great if it resonated less. But as soon as the atomic bomb was created, she recognised the destructive path humanity was on, how we have been conditioned into a destructive relationship with our planet, making it increasingly unliveable for ourselves. This is our current reality, at one of the most toxic times in history.

Her poem ‘A Litany for Survival’ serves as a guide for this transformation. She highlights how fear and scarcity dominate our lives: we fear the sun won’t rise again, we fear both hunger and being fed, we fear love and loneliness, silence and speech. Fear follows us persistently. However, Lorde teaches that it is better to speak and to remember we were never meant to survive. Fear does not have the last word.

Through her poetry she shows us that we have already lived beyond our fears and will need to do so again. She guides us in creating a future different from the one built by fear.

Defne: You are clearly part of her Black feminist legacy, continuing on her path as part of ‘a continuum of women’ without wavering. This requires significant resources including spiritual, communal and ancestral.

Alexis: It takes a lot of glasses of water. As you said, it takes communal resources and ancestral resources. It takes relationships where we feel safe enough to grow. It takes practices that connect us to generations beyond our lifetimes. It requires engaging with multiple species, which was also part of her practice. It involves sitting with what scares us about ourselves. It takes rigour to do what we are afraid to do while we are still afraid to do it. That’s the Lordean rigour.

Defne: This approach is also very much aligned with Buddhism – sitting with the pain and finding the indestructible within you.

Alexis: Lorde asks, ‘How much of this pain can I use?’

…it is an ongoing process of finding the practices (for Lorde and for me poetry is a major one) that allow us to tune into what we deeply want…

Defne: How much pain but also radical self-love and sensuality is needed in this world? I am also thinking of the book Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good (2019) here.

Alexis: Pleasure Activism was written and gathered by adrienne maree brown. She asked me to write about Toni Cade Bambara, who she identified as a pleasure activism ancestor along with Lorde (who Cara Page wrote about in the book) and others, adrienne’s own grandmother for example.

I think whatever gives us access to acknowledge our aliveness and the aliveness of other people is necessary for what Lorde calls our ‘covenant’ with the earth. Our commitment to being part of an ongoing process of creation in the universe. And Bambara was very aware of that. I ended up writing about Bambara through what I learned from her friends and students (my own mentors) about pleasure. And Black feminist literary and activist herstory is full of pleasure. Even against the odds. Alexis De Veaux tells the story of June Jordan buying her not just necessities but her favourite foods as groceries during a time when Alexis didn’t have money to buy groceries for herself. Toni Morrison writes about Bambara giving her a fall coat she felt so beautiful in she kept wearing it into winter even though she knew she would catch a cold. And we are seeing the artists of Gaza doing backflips, the children of Gaza nuzzling kittens and giggling in the most horrific circumstances. Not every aspect of being alive is pleasurable of course, but honouring the possibility of our pleasure and each other’s pleasure is a key route to remembering our aliveness in situations that might suggest numbness is the only way to get through.

Defne: And how about the erotic aspects of freedom-seeking and fugitivity – the topic you delved into in your book Spill: Scenes of Black Feminist Fugitivity (2016)?

Alexis: Part of what Lorde teaches is that the erotic, knowing what feels right to us, which also requires acknowledging what feels wrong to us, is a precondition for our action towards freedom. It’s not a once and for all feeling, though some of those clarities do change the trajectories of our lives forever, it is an ongoing process of finding the practices (for Lorde and for me poetry is a major one) that allow us to tune into what we deeply want. It’s rigorous work when our society and sometimes even our own families, and certainly most of our employers, would prefer if we didn’t act on our impulse for freedom, especially when it exceeds the profit motive. Our consumerist system would prefer that we stay with surface wants to assuage an ongoing insecurity and just buy more stuff.

But for me, when I was writing Spill based on the work of Hortense Spillers who breaks down the narrative structures and grammars of what we are supposed to want … I saw scene after scene of Black women who had to physically leave town, create fugitive names, dream alternative worlds, change their cooking practices, and invent ceremonies in order to honour their freedom desires. I have never described the book this way, but some of the essays of Spiller’s that I study are based on her reading of Alice Walker’s fiction, and Spill is almost an inverse of Alice Walker’s collection of short stories In Love and Trouble (1973) where different Black women get into different forms of trouble, mostly because of their desire for certain men in the book. In Spill, each figure is breaking patriarchal contracts, freeing themselves from the household form, and each figure is guided by a visceral want. All of those desires (for brighter greens in the pot, for the open road, for sisterhood, for space, for a man so pretty no one is sure he is a man) offer pathways to freedom.

Audre Lorde frequently visited West Berlin between 1984 and 1992, where she gave readings, lectures, and urged Black women to make their history visible. At her final reading in September 1992, at Dagmar Schultz’s home in Schöneberg, Lorde read ‘East Berlin 1989,’ continuing her fight for the disenfranchised until her last days. She passed away two months later on Saint Croix, and as per her wishes, her ashes were scattered at Krumme Lanke. © Dagmar Schultz

Defne: I wanted to ask you about the erotic possibilities in and of listening. I find this an intriguing political space when it comes to sharing our collective pain. In this age of quantum fascism, where it seems like only evangelicals are gaining ground, how can we stay committed to listening in this new and unsettling landscape?

Alexis: I am thinking of the ‘Revolutionary Hope’ conversation with James Baldwin, when Lorde disagrees with his assertion that they are both ‘outsiders’ who long against their will for the American dream: ‘I don’t, honey. I’m sorry. I just can’t let that go past.’ Lorde says to Baldwin, ‘Deep, deep, deep down I know that dream was never mine. I just knew it. I was Black. I was female. And I was out-out – by any construct wherever the power lay.’ This marks a significant divergence between James Baldwin’s and Lorde’s perspectives, but they stayed in conversation about the liberation of generations of Black people. We will never agree on everything. I don’t even always agree with myself. But I keep listening. To myself and to you. That’s the only way to be present. Fascism is escapist. Our avoidance of hard conversations can lead to dangerous consequences. If we too refuse to be present because the contradictions are so painful, we make a fascist project easier.

This is part of why it is important to say that Lorde was not a nationalist in any way. This perspective was shaped by her experiences within the Black arts movement and Black cultural nationalism, which she saw as a patriarchal force that harmed her in multiple ways. This also had to do with Lorde’s view of herself as a life form. She didn’t primarily define herself as a citizen; instead, she viewed these categories as relational. In her essay ‘Grenada Revisited’ she emphasised accountability and proximities to power, rejecting the idea of reproducing the nation for the sake of safety. Her focus was on cosmic liberation, which necessitated expanding and opening up on every scale.

…Her focus was on cosmic liberation, which necessitated expanding and opening up on every scale…

Defne: Who would be your ideal convening partners to harness all these essential keywords around work: cosmic liberation, politics of pleasure and erotic aspects of fugitivity?

Alexis: Certainly Lorde and June Jordan, Toni Cade Bambara, Marsha P. Johnson, Alice Coltrane, Fannie Lou Hamer. My beloved Durham community, particularly those advocating against genocide, sexual violence, the police state and economic injustice. My living and ancestral family of Black feminist practitioners. My family of origin who I am calling in, my grandparents, parents, aunties, uncles and cousins. And of course my aspirational cousins including the marine mammals – which are also interspecies crushes.

Defne: The ones revolting in the Mediterranean, too?

Alexis: Especially the orcas who are revolting in the Mediterranean, and definitely the spinner dolphins are just out there flipping out. And the seals who live like I do. Between worlds. All of it, all of it.