The St. Rollox Chemical Works in Glasgow, Scotland, during the 1880s.

Nº1 •

The Smell Society

In 1935, the Smell Society was founded in the UK by Ambrose Appelbe, a London lawyer. The society, which at the height of its short-lived popularity claimed H. G. Wells and G. B. Shaw among its members, had two aims. The first was to improve the quality and fragrance of London’s air, which was at the time heavily polluted with vehicle fumes. The second, more ambitious objective was to enrich the English language to better describe the experience of smells such as roast turkey, mimosa, wool or tar. An interview with Appelbe in 1937 described his plan to add 500 new words for a range of smells to the English language. The exact nature of the Smell Society’s new terminology is lost to history, as its membership dwindled with the outbreak of the Second World War. That it failed in its ambition to create a smell-conscious nation is self-evident, because our ability to describe smells remains compromised and limited. We describe the smell of something – that an odour is like something. We cannot disassociate the smell from the object from which it originates. Although the human sense of smell is not as keen as a dog, we do possess surprising olfactory acuity. It’s thought that we may be capable of detecting up to one trillion individual odours. But, as philosophers from Plato to Wittgenstein have observed, we invariably lack the necessary words to describe them.

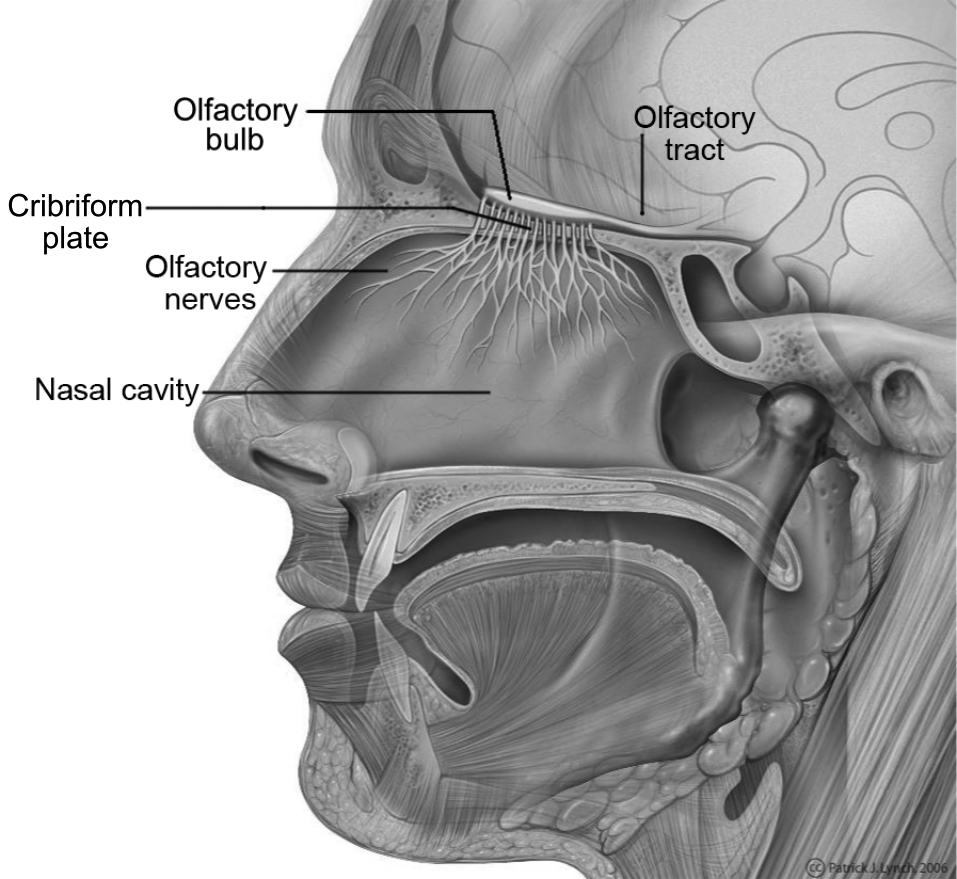

The regio olfactoria (olfactory region) on the roof of the nose has been described by some scientists as a ‘hidden door to the brain.’

Nº2 •

A Smell Experiment

A simple experiment demon-strates that while we may be able to detect multiple odours, a quirk of neurology differentiates them from the world we experience through our ears and eyes. Close your eyes and imagine Charlie Chaplin. Imagine Charlie Chaplin dressed as Elvis. Now imagine Charlie-Elvis riding on the back of a red unicorn. If we switch to imagining smells, then it becomes much more challenging. Try to imagine the smell of a rose, without recalling the vision of a rose in your mind’s eye. Imagine the smell of bananas, while not recalling bananas themselves. Finally, try to combine these two odours and imagine their mingled aroma. While the imaginary ocular world is somewhat easy to conjure, the olfactory one, mimicking the properties of smell itself, is much more ephemeral.

Short story ‘Bitch’ by Roald Dahl, published in Playboy (1974).

Nº3 •

The Scent of Desire

Smell can provoke uncon-trollable reactions. Think of the way an awful stench can make you instinctively recoil. Can pleasurable odours also inspire the same unthinking response? In 1974, Playboy magazine published ‘Bitch,’ a short story by Roald Dahl. It describes a plan to produce a scent so unbearably aphrodisiac that it provokes all who smell it into a priapic frenzy. The Ur – a perfume with a sexual odour irresistible to men – is called ‘bitch.’ Once inhaled, rational thought is impossible, and normal sexual protocols are abandoned. Dahl’s story invites comparison with Patrick Süskind’s 1985 novel Perfume, in which the fragrance that Grenouille distils from his virgin victims drives the inhabitants of Grasse to take part in a mass orgy. Like ‘Bitch,’ the participants of the climactic orgy of Perfume have no recollection of their lapse from civilised decorum, although men and women are equal partners in this explosion of unlicensed sexual activity. They have undergone a temporary atavism. However, unlike Perfume, ‘Bitch’ explicitly roots this regression in the tradition of Freud’s influential reconstructive anthropology in Civilization and its Discontents. Freud declares that prior to the moment when our proto-human ancestors stood upright, we were creatures of smell. Assuming a bipedal stance exposed male genitals to view. This, says Freud, meant that homo sapiens evolved past the baseness of odour. Smell is the realm of profane debauchery, whereas sight is where truth, reservation and collected minds reside. ‘Bitch’ helpfully illustrates this understanding. The story describes a mysterious odour that caused primitive man to behave (sexually speaking at least) as unthinkingly as a dog thousands of years ago. Freud’s beguilingly simple theory, however, is rejected by modern primatologists, who agree that sexual attraction in apes and monkeys is determined by visual, rather than olfactory cues. Pheromone sprays do exist that claim to emulate – on a more modest scale – the aphrodisiac aromas of ‘Bitch’ and Perfume. But scientific evaluations of the sprays have been sceptical. Our response to stenches continues to be much more instantly dramatic than our responses to fragrances.

L’Air du Temps

Nº4 •

Base Instincts

Following the success of the film The Silence of the Lambs in 1991, based on Thomas Harris’s novel of the same name, the character of Dr Hannibal Lecter was established as one of the most influential portrayals of a serial killer. Real-life serial killers are invariably banal, lacking a murderous presence or any otherwise arresting characteristics. By contrast, both the film and book The Silence of the Lambs heavily externalise Lecter’s abnormalities for artistic effect. The clinical psychiatrist turned killer has six fingers on his left hand and a photographic memory. He is also an accomplished aesthete. He reads the Italian edition of Vogue and murders two of his victims while listening to Bach’s Goldberg Variations. He is also credited with heightened olfactory powers. From the merest waft of air, he determines that Clarice Starling uses Evyan skin cream, and occasionally wears L’Air du Temps. He can detect the objectionable smell of a waiter’s sweaty watchband. However, Lecter is not, strictly speaking, a renifleur, an individual sexually aroused by odours, unlike his fellow inmate Miggs, who informs Clarice that he can ‘smell her cunt’ through the bars of his cell. The linkage of psychopathological deviance with a heightened sense of smell is also detailed in Bret Easton Ellis’s 1991 work of fiction – and the subsequent slasher film – American Psycho. The immaculately groomed main character, Patrick Bateman, goes through a wearying recitation of scented pomades and unguents that feature in his morning routine. Unlike Lecter, Bateman relishes less conventional aromas, such as the smell of a dying victim’s blood. Both characters display an olfactory atavism that is rooted in Freud and Darwin’s suggestion that, in the West at least, the transcendence of smell is the marker of civilisation. We can trace the origins of Lecter’s combination of aesthetic selectivity and olfactory awareness back to the character of des Esseintes in Joris-Karl Huysman’s 1884 novel À rebours. The decadent aristocrat withdraws from Parisian life, and while in the haze of smell-inspired hallucinations, amuses himself by arranging an orchestration of perfumes. While des Esseintes is clearly not a murderous cannibal or a sadistic preppie, a line of continuity remains – to be preoccupied by smell carries with it a whiff of disreputability.

François Coty helped to establish the modern luxury beauty market as we know it today. In 1904, he set out to revolutionise the fragrance industry and reinvent the perfumer’s fragrance palette.

Nº5 •

Luxurious Perfumes

Odour is paradoxical. As mentioned, it has associations with the regressively profane. It is an invisible, yet deeply embedded feature of our everyday lives. Toothpaste, shampoo, washing-up liquid – all these unremarkable products contain scenting agents that are the result of careful deliberation by their manufacturers. When we consciously address odour as an object of consumption, this is invariably in the form of perfumes and aftershaves. We purchase these commodities based on their olfactory appeal. The rise of the modern fragrance industry began in the 19th century, as artificial constituents such as aldehydes began to supplant natural ingredients. By the early 20th century, the perfume industry was booming, to the extent that perfumers were running out of appropriate names for their products. In 1933, this had escalated into a small crisis in the Parisian perfume industry. At the time, there were already 40,000 registered brands for perfumes. Many of these eau de toilettes borrowed their names from popular films, poems or musical compositions. By the 1930s, François Coty, the creator of the Coty cosmetics label, became France’s first billionaire. By the 1940s, perfume was the foremost luxury item in North America and rationing had to be introduced to ensure that demand did not outstrip supply. Today, the global perfume industry is predicted to be worth $91.17 billion by 2025. The marketing and consumption of perfume is inextricably linked with couture. Fashion and fragrance are evidently mutually supportive industries, a relationship exemplified by the success of Chanel No5 and the clothing empire of Coco Chanel.

The Radio of the Future (1921) by Velimir Khlebnikov.

Nº6 •

The Odorated Talking Picture

Modernist art and literature are fascinated with the prospect of technologically mastering smell in the service of art. Velimir Khlebnikov, writing in ‘The Radio of the Future’ in 1921, identifies odour as a point of resistance to mechanical transmission, an engineering challenge submissible to Futurist science: ‘In the future, even odors will obey the will of Radio: in the dead of winter the honey scent of linden trees will mingle with the odor of snow; a true gift of Radio to the nation.’1 In 1923, the New York Times announced the invention of the ‘Odorated Talking Picture,’ an invention capable of producing more than 5,000 individual smells with a specially odour-impregnated film. The paper dourly concluded: ‘Imagine, if you can, the olfactory congestion which would certainly be caused by the presence of even five unexorcisable odors in a modern theatre.’2 The rise of perfume also coincided with the industrialisation of cinema. As cultural products, films and fragrances embody a shared appeal to glamour and escapism. Like the production of perfume, film is a corporate endeavour but relies upon the charisma of its creator or main protagonists to ensure commercial success. The director of a Hollywood movie depended – and continues to depend – upon a team of highly specialised professionals to create a movie. Comparably, although Coty and Chanel are synonymous with their respective perfumes, they relied on the skill of industrial chemists to create them. Both are – to borrow on Walter Benjamin’s terminology – auratic. Both appear to fulfil Benjamin’s definition of the modern art object, reliant on their innate reproducibility as the key to their success.3 However, while film piracy has bedevilled Hollywood since the emergence of VHS recording in the eighties, creating a copy of a perfume remains beyond the abilities of most people. Perfume houses do employ specialist industrial chemists to deconstruct popular fragrances. Luxury perfume manufacturers are vulnerable to ‘smell-alikes,’ imitation fragrances that mimic their more expensive fragrances. In 2006, L’Oréal took legal action against Bellure, a Belgian company for creating smell-alikes of its Trésor, Miracle, Anaïs-Anaïs and Noa perfumes. The case was rejected following an appeal to a higher court, with reasons that rehearse the difficulty of working with something as volatile – conceptually and physically – as odours. It was noted that the character of a perfume alters depending on its wearer, and that preconditioning, in the form of context and packaging, affects our experience of smell. But, again echoing Benjamin’s concept of aura, the court held that the original luxury perfume possessed an intangible yet recognisable quality that consumers might confuse with cheap imitations.

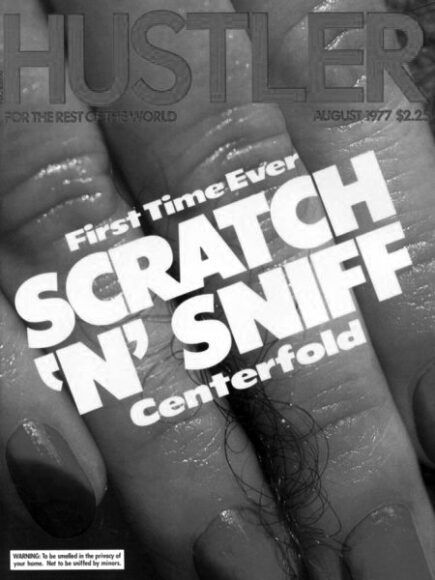

The Scratch ’n Sniff centrefold issue of Hustler (1977).

Nº7 •

Scratch ’n Sniff

In August 1977, Hustler magazine announced its first ever scratch ’n sniff centrefold. This was, the magazine claimed, in response to reader demand. The cover image featured a female hand with wisps of pubic hair between the fingers, and a cautionary message advising readers to scratch and sniff in the privacy of their own home. The erotic promise of Hustler was stymied by the reality of the odour, which smelled tamely of lilac. This was, the magazine admitted, a consequence of technological limitations. We may imagine the disappointment of Hustler’s readers. Had they read Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932), they would have realised that this problem is anticipated in the novel, in which ‘feelies’ – a kind of tactile cinema – recruit odour to heighten the stimulatory effects of erotica. The novel describes the ‘pure musk’ used as a super-additive by the scent organ to heighten the sight of a gigantic man and ‘a golden-haired young brachycephalic Beta-Plus female’ copulating.4 Despite the technology available in AD 2540 to support hyperrealism, the genuine smells of sex – semen, sweat, vaginal secretions – are absent. In part, this is obviously due to the conditions of propriety governing what a novel written in the 1930s could describe. However, it also alludes to the difficulty of finding universally appealing erotic odours. Olfactory fetishes – like all paraphilia – are highly personal. It is unsurprising that they are used successfully in private correspondence, rather than communal enter-tainment. James Joyce’s infamous letters to his wife are frequently cited as evidence of the writer’s eproctophilia, or fart fetish. Certainly, volleys of flatus ricochets throughout the 1909 letters. However, an important element of these letters is irrevocably lost to history – chiefly, the aroma of Nora’s farts. In one letter, Joyce implores his wife to ‘pull up your dress a moment and hold them in under your dear little farting bum.’5 Unlike the patrons of Hustler, we can imagine Joyce reading and inhaling with holistic erotic gratification.

Plague Doctor

Nº8 •

A Loss of Smell

A conspicuous feature of Covid-19 has been its effect on the sense of the smell of those infected. Sufferers have reported anosmia (loss of smell), phantosmia (the sensation of illusory odours, a reduced sense of smell (hyposmia) or an alteration in the character of ordinary odours (parosmia). The latter is a particularly peculiar affliction – victims of parosmia experience sudden and disturbing changes in familiar and pleasing odours, or the sudden appearance of ubiquitous stenches. This alteration in smell recalls the medieval imagining of hell, as a place where the damned were tortured with malodour as well as with fire. It also underlines the appropriateness of the plague doctor as an appropriate meme for 2020–21. A figure endowed with a ludicrously hypertrophied nose, mocking those denied their sense of smell, but also an individual deliberately screened and protected from exterior odours and contagion, thanks to their perfume-stuffed peak.

Throughout history, plagues have been attributed to malodour. Belief in the miasma theory of disease, and its correlation of foul-smelling air and epidemics, persisted into the 19th century. Although obsolete, miasma theory – the contention that diseases are spread via bad or poisonous air – invites comparison with the public health requirement to don a mask. Air has, once again, become the conduit for an intangible enemy. To be within smelling distance of another human being is to be within a zone of contamination. Wearing a mask – beaked or surgical – shields its user from their ambient odourscape, eliminating the odorous dimension of the experience. What, then, will be the olfactory legacy of 2020–21? A confusion of odours, where fragrant becomes foul – or else a troublesome gap in our volatile history, where we have screened ourselves from smell in the interests of self-preservation.

- Viktor Vladimirovič Khlebnikov, ‘The Radio of the Future’, in Collected Works of Velimir Khlebnikov, ed. Charlotte Douglas and trans. Paul Schmidt, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1987, p. 395.

- B.R. Crisler, ‘Week of Minor Wonders’, New York Times, 25 February 1940, p. 117.

- Walter Benjamin, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, in Illuminations, trans. Harry Zorn, Pimlico, London, 1999, p. 218.

- Aldous Huxley, Brave New World, Chatto & Windus, London, 1932, p. 198.

- James Joyce, Selected Letters of James Joyce, ed. Richard Ellmann, Faber & Faber, London, 1992, p. 186.