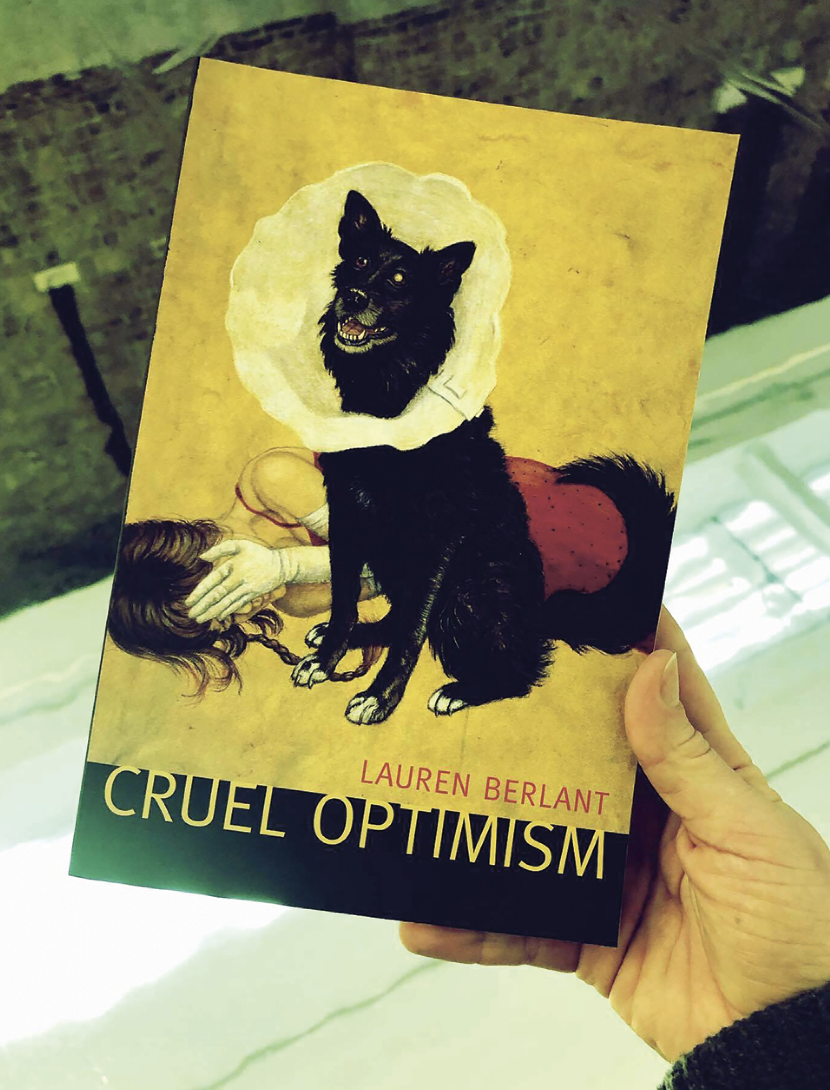

Intimacy builds worlds, says Lauren Berlant. Their work tracks how people have come to identify life with intimacy, and how the latter came to be privatised in stories of the romantic heteronormative couple as an object of desire for unconflicted personhood: the fantasy that love and life will be transparent, reciprocal and stable. In the book Cruel Optimism (2011), Berlant discusses how remaining attached to such a fantasy becomes an obstacle to flourishing in times when crisis becomes ordinary. Their method is both critical of normativity without fully rejecting it and understanding of people’s aspirations to it without fully indulging them. But as a theorist, Berlant is also invested in repurposing intimacy and making it involve all relations that are treated as a matter of course. One of the great invitations of their work, then, is to ask its readers what else they need to flourish besides dominant fantasies of the good life. What other spaces of enjoyment and relationality can we imagine, and how can we build on those attachments and patterns in order to create a world of curiosity and play that is more meaningful than the one we are living in now? This question also has political resonance: which lives count as a (good) life? In our conversation, the private and the public intersect because, as Berlant’s work convincingly demonstrates, in lived experience there is no way of telling them apart.

Courtesy: Serpentine Galleries, London

Hans Demeyer: In your work you expand the concept of intimacy, pointing our attention to other sorts of attachments.

Lauren Berlant: My contribution to the book I edited titled Intimacy (2000) was: let’s not talk about public and private anymore; let’s talk about intimacy, which transects public and private.1 The intimate is everywhere: you bring it everywhere and it circulates everywhere. It registers as intensities of attachment and recognition, inferred and explicit, that pass across people, groups and movements. At the start, I wanted to locate myself in a feminist and Frankfurt School tradition of thinking about the domestic in the world: that you begin in relation and in an atmosphere of responsivity. I wanted to start with that sense of being-with by reflecting on our attachments to the world, and on which count as being recognised as deserving to be in the world. The philosopher Jürgen Habermas associates this with modernity as such, but in the era of the neoliberal reorganisation of privacy, property and publicness we are lured into thinking that what we return to at the end of the day is ‘real’ and all other things are accidents of spontaneous encounters at, for example,our workplaces, on the train, across the room, not expressions of structural discipline at all.

The other part of that intervention was to think about queerness. What excited me was that, in order to look forward to life and have some access to objects to long for and that allow for pleasure, forms of life have to be built through repetition and return. And queers have no choice but to do it. They have to have neighbourhoods and other forms of mediated locales, places to go to and ars erotica, as well as developing unsaids around safety and desire that are so intense they become explicit. Queer practices bring the intimate into circulation to create spaces of intimacy in registers including, but not identical to, the register of freedom.

…The intimate is everywhere: you bring it everywhere and it circulates everywhere. It registers as intensities of attachment and recognition, inferred and explicit, that pass across people, groups and movements…

Hans: The Covid-19 pandemic has made explicit how the social imagination is still built around the nuclear family and work. For instance, there seems to be little discussion on other forms of intimacy and relationality – friends, community life, etc. When this is talked about, it is in terms of management: the government offers some exceptions to the youth.

Lauren: You are right that the neoliberal state matters, but this insistence on the private and the personal is also true of the social welfare state, which organised the justification for state support in terms of the family and work, e.g., tiny and specific infrastructures. One of the terrible things about neoliberal state policy is its redistribution of responsibility, meaning that in a sense no one has it: no one knows where it is because it’s circulating, often outsourced. We need to recognise that the distribution of responsibility is partly the story of the state, capital and the other institutions, but we also need to recognise its exploitation of normative life genres: many people think having ‘a life’ means having familial or long-term love that work supports while providing opportunities for the intimacies that come from regular encounters at work, after work and so on. I tend to use phrases like ‘the problem of the reproduction of life’ to leave open for analysis the dynamics among labour, intimacy, fantasy and ideology. In Cruel Optimism, there’s a chapter on the film Rosetta (1999) by the Dardenne brothers. All the title character wants is to be exploited, and she throws herself into work and relationships outside the family because then she would feel that she has a world. The cost of her self-flinging doesn’t matter to her so much: from the first shots, she’s relentless. She has an ulcer, though: her desperation to be in official economies and spontaneous attachments is eating her alive. In her book Intercourse (1987), Andrea Dworkin said that sex is a loyalty oath to being in the world and I think that’s probably truer about sex than work: people desire to throw themselves at someone so they can start a plot named life.

Still from Rosetta (1999), directed by Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne. Courtesy of ARP Sélection, Paris

Hans: Another register is that of compassion: the media commenting that it is hard for singles in times of social distancing.

Lauren: A lot of work has been done by sociologists, such as Sasha Roseneil, and the literary critic, Michael Cobb, on the ‘problem’ of securing worlds for the single and also for the old: people who are not in a unit that is associated with having a life. They are on their own or seen as burdens. There’s a reason that the single and queer people are associated with each other; their lives are often not centrally organised by the couple form and so they are not in the social imaginary of society as a repro-imaginary. The ethics of an economic ideology are revealed in what it does with and for the people who aren’t in production: babies, the sick and old people. This raises the question of being deserving. That is a political struggle. Covid has raised to the level of daily concern the debate about which lives should be protected and extended on some axis of judgment. Often the ‘essential’ workers are deemed expendable ones, if they are not unionised. And within this, all kinds of class and racial antagonisms are being played out. What does it mean to say that someone has to earn their life?

Hans: Against the privatisation of intimacy, your work is dedicated to rethinking intimacy as a way of world-making. How can we strengthen and multiply this building now that this world is ending? In other words, how can we make the leap to create another world and to not repeat this one?

Lauren: One thing I’ve learned from reading work on the Anthropocene and its variations is that it is a comforting fantasy to think that the world is ending. The fantasy of an end gives you finitude and formal satisfaction, whereas the fact of the matter is that we are living in the ending and don’t know where we are in that ending. In Stephen Jay Gould’s cancer memoir, he says that every statistic has a long thin tail at the beginning for those who don’t survive very long, a big hump in the middle for people who survive for an average amount of time, and then a long tail at the front, which is the time you live beyond the prognosis – and you never know where you are in the tail. That sensitivity to how much living is with the pressure of ending struck me as an important point.

Another thing is that I am very influenced by the anarchist attention to building worlds from where we live and where intimacy is a mode, resource and effect of how worlds are built. I have thought about this too in relation to love: is the only value of an enduring attachment the way a leap of faith and desire works out?2 In love, you hope to open yourself up to change without trauma even though your way of being will be disturbed by the pressures of the ongoing attachment. Overall, rather than leaping to judgments about intimacies and ranking them I’m more interested in moving through modes of social attachment, in squatting there, in sitting down where other people want to get out and judge effects.

Hans: Is this something you are con-sidering in your ongoing work?

Lauren: Yes. My new book, On the Inconvenience of Other People, argues that critics have an obligation to produce concepts as transformational infrastructures so that you can see how to get from here to there. In this book, I also work with Foucault’s concept of the heterotopia. The heterotopian makes these folds of life, like a really good conversation you have with somebody, or you start to take walks every day, or you decide to do a different thing in your classroom. All these things become heterotopic potentialities because they create a fold of a different kind of life right next to the one you’re already living. And one of the hardest things to recognise – and this is about ambivalence – is that you are creating new spaces from within the old spaces without replacing them. This is the problem of ‘both/and:’ you don’t stop being in the world, but you also make other possibilities. And eventually those folds can become the reference if you allow them to take on some weight or if you can gather the resources with other people to make them.

This is also how I would answer your previous question of not repeating the world but creating another one. Unlearning attachments is just incre-dibly slow and difficult and you cannot just will it. I mean, you can will your desire for it and you can make yourself ready. But the undoing of your viscera takes forever even as you get so embarrassed by your own mind and ideation. It’s like: ‘I’m not thinking that; it is thinking itself. And I have to own that because it’s in me, but it’s not real. It’s not what I identify with or want to build. What do I do with all that stuff?’ I’m interested in a non-reproductive theory of the social, but I recognise that the transitional moments are there forever.

Hans: Many contemporary thinkers focus on the work of care and community as a means to live through what you call the crisis ordinary: the sense that the ordinary is in crisis, and that crisis has become ordinary. A crucial question in those discussions is: how can we scale this relationality up from the local to another, say, national, urban or global scale?

Lauren: To me, the concept of scaling up is not so interesting, because it over presumes the neutrality of the rescaled object and often enforces a normative implication that the bigger the scale of a project, the more important it is. My work is written against any presumption like that because the effects of action take place in many locales: the nation, the city, the neighbourhood, your sense of the global, etc. I am interested in scale as a more lateral relation than a horizontal one. The question of political organising then becomes: where do you want to focus your build? Are you somebody who gives food out? Do you give your money to an NGO or do you respond to Excel sheets, such as the ones we have in my neighbourhood, where people can put down their needs? What about the circulation and communication of a counter-organisation of the world: who hears it, who is affected by it? Do you have compelling arguments for people to interrupt their life? Because the question of scale is also about risk: who is willing to risk the interruption of their specific life in order to have a lifeworld they would welcome? In short, what are you doing with the time you don’t have to make something else happen? These are the questions of scale, rather than how can you take the feeling you have and make a world for it.

Hans: A crucial concept in your work is affect, a concept to assess how one is moved by the world and how one feels to belong to the world, something which you always understand in a historical and cultural manner. Could you tell us how you came to create and conceptualise affects like ‘cruel optimism’?

Lauren: Yes, it is strange to have become in the business of re-functioning and creating affects but I’m so happy it was useful. I think ‘cruel optimism’ had a really visceral clarity for people because you can’t live without attachment as potential and constraint. Cruel Optimism does not argue that all attachments are bad or impair your flourishing, but some are, such as the current attachment to the good life fantasy. But that’s not the only one, because cruel optimism is a quality of the relationship to your object, not a quality of the object itself.

With On the Inconvenience of Other People, another work about processing ambivalence, inconvenience is the thing I want people to have the experience of: it’s a concept implicating our styles of the encounter with life rather than merely what we go through every day when we’re irritated by stuff. The book makes the argument that there is an inconvenience drive: people actually want to be inconvenienced by the world; they want to be jolted, excited, interested in stuff, to feel chosen and have curiosity, without feeling they might lose everything. At the same time, the things we let in or are forced to let in are also threats to our sense of being and ongoingness. I hope that people get interested in this problem, perceive their inconvenience and their distribution of it to others in a richer way. I am also thinking with people who are in biopolitically dominated or compromised populations who both recognise their implication in the world and see how they are both necessary and inconvenient to the reproduction of power. The question is, can we use our inconvenience against the reproduction of power’s ordinary harms, cuts, dings or attritions?

Hans: What drew you to affect theory?

Lauren: Part of my interest in affect is about how people get attached to concepts in the way they get attached to lovers: how people take abstractions extremely personally and how they throw themselves into things without a plan or ideology – sometimes it’s ideological in the sense that people throw themselves into things they have learned they should throw themselves into, but often it’s inventive. And that’s why you have to know about affect because something makes you do something while not knowing why you did it. My interest was in discovering how we register affect as a kind of belated experience. That’s why I also work on genre because genres are spaces where problems of causality are also reflected on and disturbed.

Hans: One of the genres that is very attractive to people is the enrapturing music video, a genre that is rather lacking in causality and narrativity and is foremost an affective atmosphere in which people wish to stay – ‘I want my entire life to be this music video.’ It’s not dissimilar to the end of a romantic film where the love interests recognise that they belong together after which the film stops and the hardest part of building a life together is not shown. But as with the music video, that scene installs a longing for recognition to stay as an affective intensity.

Lauren: That’s how people live, right? When they find some happiness, they just want it to go on like that forever. That’s how Freud defines pleasure: it’s the state you want to be in. But this affective state doesn’t have to feel positive the way ‘pleasure’ suggests: it could feel like affective comfort food, sometimes provided by the return of shame, or loneliness, or asceticism, or ennui, any state where people get to coast the way they want. Media that offer ecstatic atmospherics – the music video, but also TikTok, mumblecore or lo-fi – are very powerful because they fold an alternative world of fantasy and fascination from where people live. José Muñoz would talk about this as a kind of utopianism. You create utopianism not because you are getting a future, but because you experience affectively a world you want to live in before there is an infrastructure for it. In the DIY and professional music video, artists usually find ways to demonstrate pleasure without making viewers feel small, modelling a freedom someone might want to imitate or be proximate to, as in fan or stan culture. I’m a little bit more sceptical because I wonder: does the aesthetic pastoral matter or is it mainly a ruse of alternativity? The question is how we take up a position in our pleasures and attachments.

Hans: But then working on these platforms, such as Instagram and TikTok, requires an enormous amount of labour that goes unseen, and which is exploited by those platforms.

Lauren: People are into self-exploitation if they can make something through which other people will find them. You and I are writers, what’s the difference? Most posters are not influencers. How people want to put themselves in the position to be found – that’s a really complicated thing. Of course, I don’t disagree that we are providing monetisable value in exchange for our circulation of interest. It would be better if there was no property relation to art and performance and other forms of labour.

Hans: It does seem a depleting way of having to be found. You constantly need to post on these platforms again and again without any guarantee of being successful.

Lauren: But what work isn’t depleting? People are just putting it out there, like rap and house music in the early days too. Maybe it’ll have a hook. The whole idea of a hook is so central to pop culture and in The Female Complaint (2008) I argued that the central message of pop culture is ‘you are not alone.’ And even the gesture of making is a sign that you know you’re not alone. The question is, will you be found and in the way you particularly want?

I do a lot of writing exercises in my classes and I tell my grad students: you write because you want to be found. But I don’t mean you want to be idealised although that’s often what wanting to be found means, because if you’re not idealised, you’re nothing in many registers of mass society. To my friends suffering from writer’s block, I always say that the thing they can’t bear is that their writing is a demonstration of their ordinariness. All of their grandiosity is in their head and then they put words on the page and their approximateness produces dread and the sentiment of, ‘Oh, I don’t know if I can live.’ And I have experienced it, and everybody experiences it, but I love my ordinariness. I find it comic. There is no middle ground when you have to be a star in order to be anything and I much prefer the middle. There are a lot of goofballs on TikTok who are not trying to be famous but who are showing up to be part of the aesthetic. So we turn to the question of the intimacy or the impersonality of belonging – a genre of intimacy.

On social media there is a desire to be found whether or not your thought is spontaneous or worked on: it’s live, you want people to go there with you. That’s the thing about the impasse: how do you get people in there with you to help to move it somewhere? But I agree with you that it’s better for life if you don’t confuse the idealisation drive with world-building. If everybody needs some space of self-idealisation, can we think of the space where they’re happy to encounter themselves as distinct from being perfect or being invulnerable? And would that shift change people’s relation to their action, production, aesthetics?

…the idea that ‘X’ kind of being, thing, encounter, signified or concept has many others, not just one, is really important to me. The idea that antinomy hides internal connections, cathexes and dependencies too.

Hans: Could you speak about the intimacy of writing, and especially about your collaborative work with Kathleen Stewart with whom you wrote The Hundreds (2019). To me the work enacts ambivalence, which, as you say, is not something negative but rather being pulled in many directions.

Lauren: Interestingly, the word ‘ambivalence’ doesn’t appear in that book, but ambivalence as a feature of engagement really does. I was trained in deconstruction, so the idea that ‘X’ kind of being, thing, encounter, signified or concept has many others, not just one, is really important to me. The idea that antinomy hides internal connections, cathexes and dependencies too. Then I read about overdetermination in psychoanalysis: that you do not only love or hate the object of your desire, but that you and your object are in a tangle of tones, causes and effects that vary in intensity over time. Katie and I are quite different in the face of that, because she’s interested in getting to the gist of actual objects and the haunted atmospheres of relation whereas I tend to dilate the encounter and develop multiple ways of being in it. In fact, we have influenced each other quite a bit: ‘Collaboration is a meeting of minds that don’t match.’3

Collaboration is an amazing thing. It makes teaching possible, makes conversations like the one you and I are having possible and it makes thinking with another person really exciting and intense. It is something you need training in and a lot of ego armour for, in the sense that you need to be able to say: ‘well, I’m going this other direction, but I still think we’re on the same page as far as the process goes.’ We both think the work on The Hundreds made us better writers. Because of the spareness of the concept: each piece is one hundred or multiples of one hundred words long, so we had to cut things down. But also, we really were committed to seeing something and to seeing that anything could become a concept if you make a space for it where it could resonate beyond its thingness – to recognise that thingness is a resonance. That’s what The Hundreds means to me as a critical project: it’s a craft for extending a concept/object/scene into causalities and effects that provide twists and changes to their dimensionality. It’s about being drawn into situations or dynamics and following them out to a limit.

- Lauren Berlant, ‘Intimacy: A Special Issue’, Critical Inquiry, vol. 24, no. 1, 1998, p. 282. Berlant is the George M. Pullman Distinguished Service Professor of English at the University of Chicago. Their most recent publications include: The Hundreds (2019, with Kathleen Stewart), Sex, or the Unbearable (2014, with Lee Edelman), Desire / Love (2012), Cruel Optimism (2011) and The Female Complaint (2008).

- Heather Davis and Paige Sarlin, ‘On the Risk of a New Relationality: An Interview with Lauren Berlant and Michael Hardt’, Reviews in Cultural Theory, 15 October 2012, http://reviewsinculture.com/2012/10/15/on-the-risk-of-a-new-relationality-an-interview-with-lauren-berlant-and-michael-hardt/; accessed 19 January 2021.

- Lauren Berlant and Kathleen Stewart, The Hundreds, Durham, NC, Duke University Press, 2019, p. 5.