Præludia sponsaliorum plantarum (‘on the prelude to the wedding of plants’) was the first academic paper written by Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus. Published in 1729, its findings elicited an indignant response from many who found the notion that God’s lovely flowers had sex blasphemous.

fig 1:

Blooming Bridal Bed

The belief that plants are a sexual organisms, whose organs are merely ornamental, finds its roots in antiquity. Naturalists did use the words ‘female’ and ‘male’ to describe certain species, in a metaphorical way based on certain attributes such as spines, thorns, delicate flowers, not according to their reproductive parts. However, as modernity dawned, this perspective began to transmogrify. On New Year’s Day 1729, a young Swedish student, by the name of Carl Linnaeus, presented a handwritten essay titled ‘Praeludia sponsaliorum plantarum’ to his patron Olof Celsius, professor of theology at Uppsala University. In a note accompanying the essay, Linnaeus writes that he is following an old custom by surprising his benefactor with a short poem to celebrate the new year. However, after confessing that he is not well-versed in poetry, he instead offers the ‘fruit from the little crop that God has granted me.’ This ‘fruit’, inspired by the revolutionary work of the French botanist Sébastien Vaillant, comprised his botanical ideas on plant reproduction.

Linnaeus begins by praising the springtime sun and its power to awaken nature from its winter sleep. Sap rises in the trees, leaves unfurl and bulbs emerge to bring forth flowers. Romance fills the air as the animals feel the springtime urge and start their courtship rituals. But what about the plants? Linnaeus argues that during this season the floral kingdom is adorned in wedding attire. The title page features a doodle of the matrimonial ceremony of the dioecious dog’s mercury plant. Under the illuminating sun, you see the pollen or ‘sperm’ floating on the breeze from one plant fertilising the other. In an eyebrow-raising manner, Linnaeus compares the love life of plants to humans. He calls the stamen a ‘groom’ and the pistil a ‘bride,’ who consummate the marriage when the flower blooms. He writes: ‘The flowers’ themselves contribute nothing to germination, but only do service as bridal beds which the great Creator has so gloriously arranged, adorned with such noble bed curtains, and perfumed with so many soft scents that the bridegroom with his bride might there celebrate their nuptials with so much the great solemnity.’ While Linnaeus took his poetic license to the extreme, the radical nature of the idea that plants have rich and variant sexual lives continues to permeate.

Commonly known as butterfly pea, the Clitoria Ternatea is native to tropical Asia including regions in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. The genus ‘Clitoria’ stems from ‘clitoris,’ so-named because of its uncanny resemblance.

fig 2:

Flos Clitoris

Although botany might appear to be a rather prudish pursuit, it is filled with all types of lewd language. Even before the discovery of sexual reproduction in plants, many carried sexual connotations, usually from an anthropocentric perspective. Perhaps the aptest example of this is the so-called butterfly pea. The common name sounds rather innocent. The Latin – Clitoria ternatae – is more suggestive. The first time I encountered this plant was well outside its native habitat of South Asia, in London’s Princess of Wales Conservatory of the Royal Botanic Garden. The conservatory houses several fused greenhouses with different climes and vegetation. While walking through the jungle green-house, I came across a vine spiralling upward and adorned with blue flowers. The name tag between the foliage made me snicker. The resemblance is uncanny, albeit that the flower is bright blue and resembles not so much the clitoris but the entire vulva. After leaving the gardens, as I made my way through the streets of London, I wondered, who came up with the title. The letter L on the little name tag indicated that Linnaeus was responsible, yet my research unearthed that the name was even older. One of the very first descriptions of the butterfly pea appears in the Ambonese Herbal (1741–1750), written in Dutch by a German naturalist working for the Dutch East India Company, Georg Everhard Rumphius. The chapter ‘blue clitoris flower’ is based on several local colloquialisms. His explanation of the name is rather straightforward, referring to ‘that part of the female conch …. the folds that are displayed in the opened conch, and which resemble this flower more.’ Rumphius’ encyclopaedic style of writing often makes him difficult to follow. Essentially, as with my own observations, the ‘clitoris flower’ is a bit of a misnomer since it more closely resembles what he calls the entirety of the ‘female conch’ (he uses the Dutch word schulp, meaning ‘shell’ or ‘scallop’). And this is not the only time Rumphius is explicit. There is a fungus he calls Phallus daemomum, due to the evocatively phallic shape of its mushroom. He openly discusses topics from venereal disease to abortion. There is an uneasy tension with this chapter in the history of botany. In the BBC series The Private Life of Plants, David Attenborough allegedly refused to elaborate on the Latin name Amorphophallus titanium for the biggest flower in the world, the titan arum. The famous British documentary filmmaker deemed the erotic connotations inappropriate for family viewing (Amorphophallus titanium translates to ‘deformed titan penis’). Rumphius was unfamiliar with titan arum, although much knowledge of its humungous inflorescence stems from his description of the closely related elephant yam (Amorphophallus paeoniifolius), which he calls Tacca Phallifera or ‘phallic-bearing Tacca,’ writing: ‘in the centre of this funnel grew a phallus, two fingers thick on the bottom, three on top, draped with a little skin.’

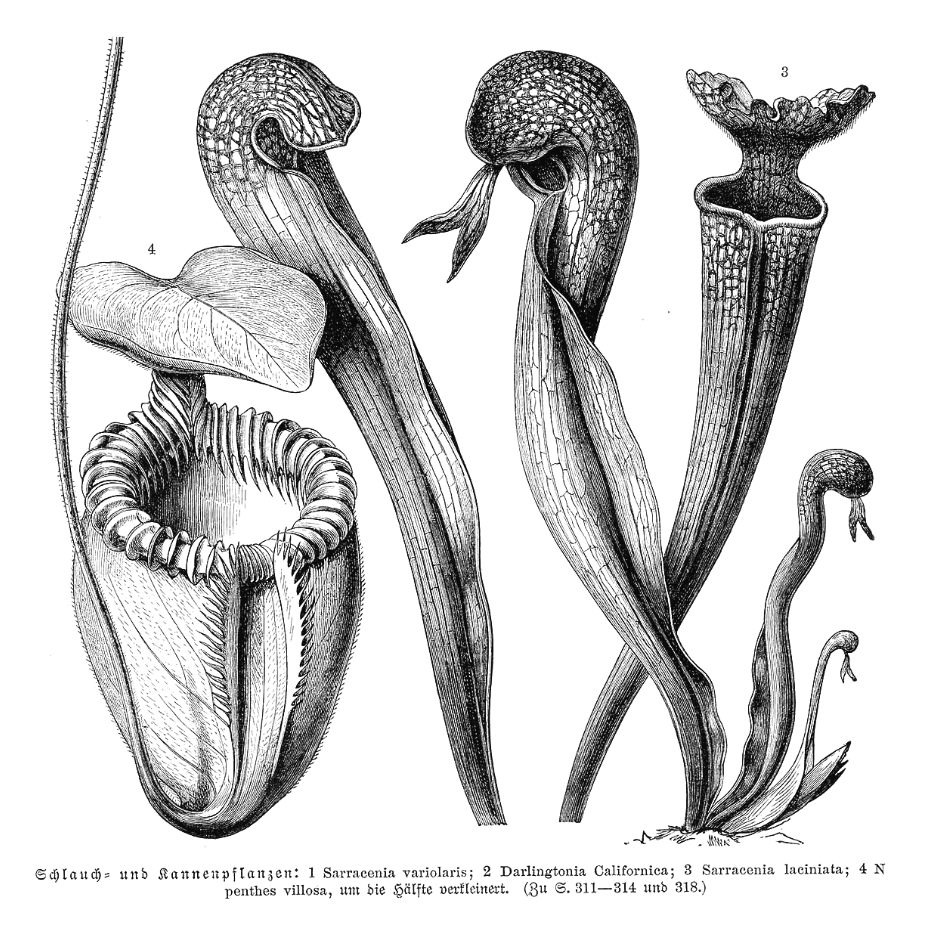

Mary Treat made strides into the knowledge of the engorged fronds and deadly nectar of the hooded-pitcher plant.

fig 3:

Fleurs du mal

On 5 May 1876, Charles Darwin received a letter from one of his American correspondents, Mary Treat, a botanist and entomologist who made her living writing scientific articles and popular science books. This would be the last letter in a lively correspondence stretching across many years, over different topics. Treat ends the exchange by saying she is working on the hooded-pitcher plant, Sarracenia variolaris, which grows in the peat bogs and swamps of Virginia and Carolina. Like the other species in the Sarracenia genus, this plant is characterised by a rosette of trumpet-shaped cups with a little roof overhead. In Treat’s opinion, the hooded-pitcher was a good candidate for the category of carnivorous plants. Both Treat and Darwin shared a fascination for these sagacious creatures. In her book Home Studies in Nature (1885) Treat details her amazement at how these plants ‘reversed the regular order of nature, and, like avengers of their kingdom, have turned upon animals, incarcerating and finally killing them.’ Upon closer inspection, she notices the effectiveness of this insect trap. When she cuts open some pitchers lengthwise, they are almost filled to the brim with the remains of partly digested victims. The success of this trap is partly due to the purple-red veins on the inside of the hood, which attract insects like colourful flowers. However, the real bait is the nectar, secreted from the rim of each pitcher. And there is another reason to call these pitchers fleurs du mal, or flowers of evil.

According to Treat the nectar oozing from the brim is not your normal sugary secretion. If a victim drinks from the nectar, it becomes intoxicated, loses its grip and ends up in a pool of liquid full of enzymes in which it is slowly digested. It first appears that the ‘terrible Sarracenia was eating its victim alive,’ Treat asserts. Immediately she doubts whether ‘terrible’ is the right word: ‘the plant seems to supply its victims with a Lethe-like draught before devouring them.’ The name ‘Lethe’ refers to a mythical river that ancient Greeks believed flowed through the underworld, like the Styx. A drink from this river would make you forget everything. In other words, Treat argues that the nectar of the hooded-pitcher plant is spiked. She speculates that the plant intoxicates its victims, as a form of palliative care. To clearly see the effects of the lethal brew, she experiments with a large Florida cockroach. When sober this creature is swift, agile and almost impossible to catch. After a sip of the intoxicating beverage of Sarracenia, the roach becomes docile, gently swaying his antennae back and forth. As soon as he starts walking, he stumbles about in a drunken frolic. When Treat checks on the cockroach the next day, she discovers that he never woke up from the night of drunken indulgence. Treat’s suspicion turned out to be correct. Several Sarracenia species produce low concentrations of the potent nerve poison called coniine, also found in the more popular and highly poisonous plant hemlock (Conium maculatum), the plant that provided the poison that Socrates was forced to drink at his trial. Perhaps it should be renamed the philosopher’s cup.

In Greek mythology, Lethe is one of the five rivers of the underworld of Hades. Lethe was also the name of the enchanting spirit of forgetfulness and oblivion, with whom the river is often associated.

fig 4:

Potent Elixirs

Perhaps one of the most visually stunning attractions of any botanical garden – the bee orchid takes its distinctive appearance to entice scoliid wasps. The insects attempt to copulate with the lower-lip of the flower, and in the process, pollen gets stuck to their head. Quite remarkably this flower attracts insects with the promise of sex, rather than food.

The word ‘orchid’ is derived from the Greek ‘orchis,’ meaning ‘testicle,’ referring to the shape of the tubers. The testicle-shaped tubers of the bee orchid were once well-known aphrodisiacs in Europe; consumption was thought to increase lust for mistresses and awaken unchaste urges. Many naturalists were also convinced that there was something amorous about the origin of this orchid. For instance, Athanasius Kircher’s book Mundus Subterraneus (The Underground World, 1682) contains lengthy speculation on a group of terrestrial orchid species he calls ‘satyria,’ named after the cloven-hoofed followers of the Greek god Dionysus, who were known for their lewd and lascivious behaviour. Kircher cites folklore and the tales of shepherds who claimed that these satyria sprouted only in places where animals mated. The plants were said to be the progeny of accidentally spilt animal sperm during lovemaking.

Kircher’s curious reasoning that orchids are the side-products of animal copulation also serves to elucidate another important observation. According to him, satyria hold a strange protean power that enables them to take the floral form of monkeys, dolphins, wasps, flies, grasshoppers and of course bees, as with the case of the bee orchid. Kircher endeavours to show that this form is related to its animal origin. For instance, he argues that the bee orchid germinates from bull sperm. This raises an important quandary: why, if the bee orchid is the by-product of bull semen, would the flower not resemble a bull? The explanation for this misdemeanour is as follows: Kircher was a staunch believer in spontaneous generation. He was convinced that decaying carcasses of animals produced wasps, bees and other insects. In a similar fashion, he argues that the spilt semen of stallions or bulls produces an ‘imperfect’ image of its progenitor. According to his now evidently fanciful hypothesis, that’s why orchid blooms resemble wasps or bees.

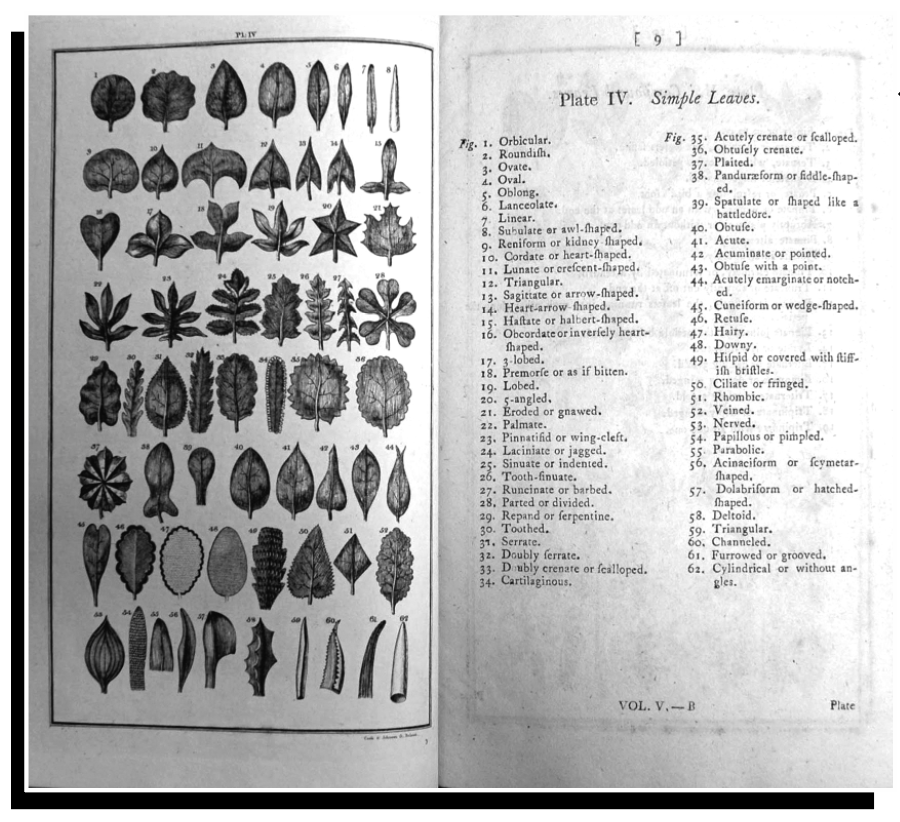

Systema Naturae is a grand taxonomy of nature by Carl Linnaeus that was published in 1735. The categorisations imagine that plants have vaginas and penises (some people of his day referred to plant sexuality as ‘coitus of vegetables’). This was obscene enough to shock female modesty, and beyond all decent limits.

fig 5:

Botanical Brothel

In his seminal work Systema Naturae (1735), Linnaeus presented a grand scheme: an all-encompassing classification of nature. The document consists of a dozen, large folio pages, showcasing a unique taxonomy of the plant kingdom that would prove to be hugely influential. The sex organs – the male stamen and the female pistil – are laid out as the key traits for identification. Linnaeus’ sexual methodology organises all plants into twenty-four classes according to the number of male stamens in the flower. By counting the female pistils, he then sub-divided each of these classes into orders. The first class he calls monandria, the second diandria and so on. Whilst the first order is monogynia, in which, as with the classes, each subsequent order has an extra pistil – take, for example, Linnaeus’ own heraldic flower, the twinflower (Linnaea borealis) – the flower produces one pistil and two stamens, as a result, the plant belongs to the class diandria and the order monogynia.

While this might paint a formalistic picture, tracing the etymology of the labels instead conjures an intriguing portrait of domestic intimacy. –Andria and –gynia are derived from the Greek words aner, meaning ‘husband,’ and gyne meaning ‘wife.’ Linnaeus jokingly nicknamed his wife, his monandrian lily – a female with one single husband. However, monogamy is not the rule in the floral kingdom. On the contrary, oftentimes there are many more stamens in a flower than pistils. The aforementioned twinflower is the botanical equivalent of a three-way. The autumn crocus (Colchicum multiflorum) has six stamens and one pistil, divided into three stigmas, making it part of the class hexandria and the order trigynia, which, loosely translated, conveys six men sharing a bridal bed with three women. At some point, Linnaeus stops counting. All flowers with twenty or more he puts in the class polyandria. Thanks to his ground-breaking work botanical jargon is full of sexual innuendos.

This classification system for the plant kingdom became very popular. It made botany accessible to the wider public. No longer did someone need to attend university to learn how to identify plants. Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) praised Linnaeus’ work as Ariadne’s thread, which the philosopher said allowed botany to find its way out of a dark labyrinth. At the same time, in his botanical letters to Madame Delessert (Lettres sur la botanique à Madame Delessert, 1774) Rousseau intentionally avoids all reference to the sexuality of plants. Other contemporaries went even further than censorship. Linnaeus’ botanical innuendo was on a collision course with the social mores of his time, partly due to the fact that botany was the only scientific field accessible to women. One of the first attacks came from the Prussian botanist and director of the St Petersburg apothecary garden, Johann Siegesbeck (1685–1755). In 1737 he published a book scorning Linnaeus’ sexual system as ‘loathsome harlotry,’ denouncing the idea of plant sexuality on the authority of the Bible, as nowhere in the Old or New Testament is it mentioned that plants sexually reproduce. He simply could not believe that ‘bluebells, lilies, and onions could be up to such immorality.’ Siegesbeck was convinced that God would never allow such ‘shameful whoredom!’ Linnaeus would get his revenge for the moral policing and slander. He sent Siegesbeck a seed packet of a newly discovered species with the Latin name Cuculus ingratus. Curiously, Siegesbeck sowed the seeds and waited. As soon as a few sprouts began to grow, he realised that he had been duped. This was the Sigesbeckia orientalis, meaning ‘ungrateful cuckoo,’ a small, ugly weed that Linnaeus named after Siegesbeck.

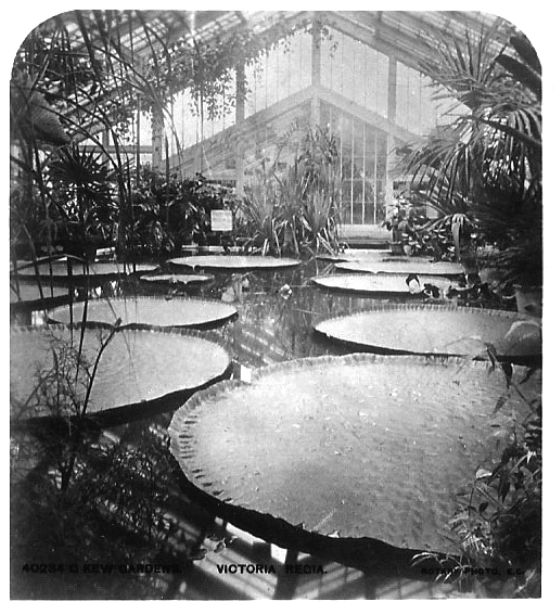

The world’s largest Victorian glasshouse,

Royal Botanical Garden, Kew.

fig 6:

Victoria Waterlily

In 1685 Agneta Block became the very first horticulturalist to raise a fruit-bearing pineapple (Ananas comosus) in the cold, harsh Dutch climate. On her Vijverhof estate, just outside of Utrecht, she erected special glass greenhouses to house exotic plants. Her horticultural success is captured in a family portrait, where we see some of her prize specimens in the bottom left corner, including the fruiting pineapple. For her achievements, she received a silver medal figurine depicting the goddess Flora together with a pineapple. The base is engraved with the Latin proverb: Fert Arsque Laborque Quod Natura Negat (‘Art and labour succeed where nature fails’). This proverb is emblematic of the Enlightenment. It was believed that humans were capable of helping nature with artificial improvements. In horticulture, the most crucial intervention proved to be the introduction of glass. By the 19th-century glasshouses became affordable for upper-class citizens, and avid amateur botanists started growing orchids and other tropical delights. Glasshouses also facilitated displays of colonial pride and supposed Western dominance. Many European botanical gardens have a glasshouse specifically dedicated to the giant Amazon water lily (Victoria amazonica), named in honour of Queen Victoria. It was discovered in shallow tributaries of the Amazon River in Bolivia. A colossus compared to its European cousin (Nymphaea alba), the leaves of the Victoria amazonica can reach a diameter of two metres, covering the surface of the water like round air mattresses.

Approximately once a year, a thorny bud emerges. This flower blooms for only two nights, and during this time an eye-catching transformation takes place. For Amsterdam’s Hortus Botanicus, this event has become a special occasion. The botanical garden stays open late – the perfect romantic date activity – and couples flock to watch the flower unfurl in its pale evening gown. As dusk falls, the spiky sepals retract and bright white petals appear, producing a sweet pineapple scent. Both the colour and the odour are irresistible to a certain species of beetle (Cylocephata castaneal) who is active around this time of night. Multiple beetles enter and willingly lock themselves in by waiting until the flower closes. While confined, they are served a dinner of sticky and nutritious pollen. When the flowers open up again, the beetles stumble out in a post-coital daze. The petals are now pink and the flower no longer produces a detectable odour. The flower has undergone a sex change: first, the male blooms and releases pollen, then by the next night the female reproductive parts are receptive. After she is visited by beetles covered in pollen dust, she closes her petals for a final time and sinks to the bottom of the pond to form seeds.