One of the most common aliases for poppers is ‘video head cleaner’, for some reason.

fig 1:

Rush is a room odorizer

Poppers are the now pretty well- known party stimulant passed around at gay nightclubs, hen parties and school discos alike. These little brown bottles, filled with a nail-varnish-remover-smelling liquid that burns if it touches the skin, have moved from being a treatment for angina to a dangerous disease-spreading-sex-stimulant for gay men, and finally to a pretty mundane head-rush widely available online or in the local corner store. When opened and huffed by the user, one gets a short euphoric head rush. The face contorts into a stupid smile, the heart pounds, blood rushes to the skin and a short- lived loose giddiness follow. It is appreciated by many, treated as a harmless teenage indulgence, a silly kick, or a ubiquitous tool. The little brown bottle has remained largely the same the whole time and its shape and many various names have now attained a symbolic status. To some, it is a symbol of the gay sexual hedonism of the pre-AIDS era, used equally by gay men on the dance floor and the dark room; its head rush also helps the body to relax. To many it alludes to anal sex and is seen as a necessary gateway drug to sexual taboos. But, like many things that emerge in gay subcultures, it has now gone mainstream and is widely known and used by all ages and sexualities in various contexts from the seediest sex clubs to teenage bedrooms.

Of course, this is not what it actually is. It is a ‘room odorizer’ or also, when people used VHS tapes, a ‘tape-head cleaner’. In order to sell this chemical it has to be labelled as something else. Why would anyone want their room to smell like sour solvents, or how could anyone believe such a porker? What is significant is how this has become general knowledge, shared by many, a practice that still remains unnamed as such. How much we know, that for whatever reasons, some substances can never be articulated in words? We live strange lives where euphemism and a certain wink, wink, nod, nod can stand in for some of the most life-changing and moving things that happen to us both emotionally and physically. Obviously poppers are just the tip of the iceberg, there is so much more down there in the depths. Why is it that such events and behaviours remain somewhat bracketed, known but not included in the main text? It’s always done as if they might be able to appear later, in the future, at some unspecified time when things will be more free and more open than they are now. Postponed indefinitely. Until that promised moment we all participate in having to talk around such things, or better, not talk of them at all.

This introduces the theme of this series of examples: discretion. A practice that separates an act from its naming, or its visibility. Discretion comes into play when certain practices, lifestyles, and identities are, for whatever reason, unable to be spoken about freely. Where subtext, suggestion and subterfuge have to come into play. Throughout the various examples that follow, it is important to spell out the fact that the very act of being discreet already suggests that something is within a common knowledge, that the practice is already shared by a group and constitutes a community or social form but that it is not yet ready or allowed to be spoken of. Discretion is the modal twin of censorship and oppression, and it’s produced by a form of social management that forever promises a more enlightened horizon while always exerting the power of a repressive present.

American pianist Liberace smiling and talking to the press as he leaves the court, following his successful libel action against the Daily Mail over a slanderous article, London, June 18 1959.

fig 2:

Liberace was heterosexual

In 1959, Liberace sued a British newspaper for libel. In this case, Liberace considered the phrase ‘fruit-flavoured’, published in the Daily Mail’s ‘Cassandra’ column, to insinuate that he was homosexual. The trial established the singer’s heterosexuality in court and he won the case to the sum of £8,000, which was widely publicizsed as a landmark amount. The following is an abridged adaptation of the legal transcript of Liberace’s cross-examination in court and demonstrates how the varying signifiers mentioned in the article are brought up but always taken to a safe place, a kind of family-friendly asinine asexuality. Liberace is clearly skilled at playing with the ambiguity of visual and sensorial signifiers but what is striking is that to a contemporary audience we are left dumbfounded as to how they seem to miss the obvious! Truly an example of the most expensive and well publicized elephant-in-the-room of its time.

QUESTION:

Was there anything sexy about the performances at all?

LIBERACE:

I am not aware of it if it exists. I am almost positive that I could hardly refer to myself as a sexy performer. I have tried in all my performances to inject a note of sincerity and wholesomeness.

I am fully aware of the fact that my appeal on television and personal appearances is aimed directly at the family audience.

QUESTION:

Do you ever tell what we know as dirty stories?

LIBERACE:

I have never been known to tell any so-called dirty stories. I have told of experiences that happened to me that might have been termed double-meaning in referring to some of my sponsors. Among them was a very famous paper company who among their products make toilet tissue. I mentioned them among my sponsors and the audience found it very funny. But the audience in no way found it offensive.

QUESTION:

In the booklet ‘The Liberace Story’ you are quoted as saying you had turned down marriage proposals because you are still looking for a girl ‘just like Mom.’ Is that correct?

LIBERACE:

That’s right.

QUESTION:

The booklet says you are ‘the hottest personality ever to melt the TV airwaves.’ Won’t you agree that you have sex appeal?

LIBERACE:

No. I consider sex appeal as something possessed by Marilyn Monroe and Brigitte Bardot. I certainly do not put myself in their class. [laughter]

QUESTION:

Do you use scent or scented lotion?

Liberace:

I use aftershave lotions and underarm deodorants.

QUESTION:

And are they scented?

LIBERACE:

Yes.

QUESTION:

When you come into a room at a press conference, does a noticeable odour come with you?

LIBERACE:

I would not say it is an odour. I would say it is a scent of good grooming, that I smell clean and fresh. I always smell clean and fresh. I have noticed the smell of the press many times. [laughter]

QUESTION:

When you came to England in 1956, had you reached the summit of your career in the United States?

Liberace:

It is presumed by many that I had.

QUESTION:

How did the Cassandra article affect you?

LIBERACE:

I was deeply shocked, and my only thought at the time was that it would certainly have to be kept from my mother. I felt this so strongly because my mother has a hypertensive heart condition. Further, I know she is extremely proud of her children, perhaps a bit more proud of me. Unfortunately, it was brought to her attention by someone.

She immediately became very ill and was attended by a physician. It was decided by everyone concerned with her welfare that she should leave the country.

QUESTION:

Are you a homosexual?

LIBERACE:

No, sir.

QUESTION:

Have you ever indulged in homosexual practices?

LIBERACE:

No, sir, never in my life. I am against the practice because it offends convention and it offends society.

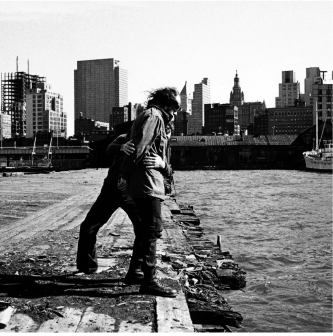

Vito Acconci’s performance project Security Zone (1971), which took place at New York City’s Pier 18.

fig 3:

That time when Vito Acconci cruised the piers

In 1971, the celebrated American performance artist, Vito Acconci, staged one of his lesser-known early performance works on one of the piers that jutted out from New York’s downtown district. The performance invited the audience to attend to him one by one as he waited at the end of the pier. He would then disclose a piece of information that, if made public, would be considered ‘disturbing’, a piece of information that could be used for blackmail.

We have to acknowledge the cultural significance of the piers in New York at that time as they were extensively used for public sex amongst men. Today there is the possibility to disclose the history of those spaces thanks to the legacy of many artistic luminaries we know today, from Keith Haring, who avidly decorated the spaces there to David Wojnraovic, whose writing describes the queer street life of the city in living colour. However, there is a significant breach between the context of Acconci’s performance and the era in which the artists spoke openly about that space. It wasn’t until the AIDS crisis and the extent to which it decimated cultural life in New York that the sexuality of artists became intrinsically politicized and allowed them to work openly in public as gay men. Needless to say that back in the early 1970s, the cultural milieu around Acconci would have known clearly the context of his performance and his use of the tropes around homosexual blackmail as material for his own work. Looking back, it’s difficult to know his intentions. This work would be undoubtedly edgy at the time in terms of its content and location but it was exactly because it carried no personal risk for Acconci that this work was possible for him while many other artists laboured on and negotiated the closet for many years in order to maintain careers and regular incomes. Yet it is the very unspoken nature of this work that has also undoubtedly contributed to it being put to the side in his legacy as a performance artist.

In this work, discretion was a material and disclosure a performance. It is important to contextualize the risk involved in discretion, the fact that although it may be a solution that manages difference for a moment, it inadvertently puts those who are forced to be

discreet at risk of blackmail, arrest, violence. Although, for Acconci, it was perhaps a demonstration of his personal bravery or boldness as an artist, for many others it functioned as an illicit and cruel form of social control. Discretion creates a void, an absence which was instrumental in the political indifference that characterized the response to the AIDS crisis.

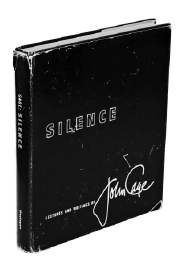

‘Lecture on Nothing,’ which is published in John Cage’s ‘Silence,’ is a classic, studied and often recited. One of its much-quoted lines is ‘I have nothing to say, and I’m saying it / and that is poetry / as I need it’

fig 4:

John Cage

‘I have nothing to say, and I’m saying it / and that is poetry / as I need it ’ – John Cage

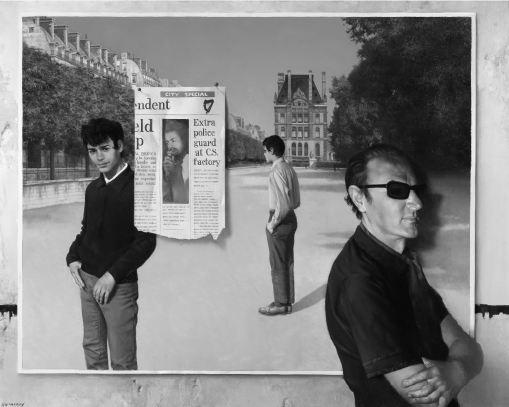

Portrait Figures (Self-Portrait), 1972 National Gallery of Ireland Collection

fig 5:

Patrick Hennessy was simply a successful commercial painter

In 2016, the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) staged a retrospective of the painter, Patrick Hennessy, entitled De Profundis. Often overlooked in the Irish context, where he established his significant career, the exhibition focused for the first time on the artist’s personal biography and his sexuality. Many of Hennessy’s works are coded or composed of visual signs that, to the initiated, describe and depict homosexual life at a time when gay men were subject to social and legal persecution. I discussed ideas of identity and discretion in Hennessy’s life and work with the curator of the exhibition, Seán Kissane.

RICHARD JOHN JONES:

Patrick Hennessy is now a canonical Irish painter but there is so much more complexity regarding his identity. Was your exhibition the first to use his biography as a way of structuring a retrospective?

SEAN KISSANE:

Yes it was, and it’s quite interesting that you would use the word ‘canonical’ because in some ways he is but mostly only to a discreet coterie of people, either queers or their wider circles, and some people who are interested in modern realist painting. From the point of view of making a show using his biography, no, there hadn’t been a retrospective in Ireland. Strangely, up until his death in 1980 he was the most commercially successful painter in the country so it is extraordinary that he would have gone from that position to being almost entirely forgotten.

RICHARD JOHN JONES:

So how did you discover his work and how did his legacy become forgotten?

SEAN KISSANE:

The only reason I knew of Hennessy was because there are two works in the IMMA collection that are shown quite often. We owned them is because they were in the founding collection of IMMA, which was originally owned by Gordon Lambert who was, you guessed it, queer. So in terms of networks within networks, Hennessy’s position within the Irish national collection was determined by the fact that a queer man bought them in the 1950s and then gave them to IMMA. Otherwise that link might not have ever been made. The reason for him being forgotten was partly to do with commercial forces; he didn’t have a gallery representing him after his death, for example. His collection was dispersed and for an artist’s legacy to survive, there really needs to be a gallery and an estate functioning and promoting and selling the work, commissioning texts, etc. In Hennessy’s case that didn’t happen.

RICHARD JOHN JONES:

But did homophobia have something to do with that too?

SEAN KISSANE:

I think what you have to compare it to is those people who died and did have that kind of management. I’m thinking specifically about Francis Bacon, who was (in)famously managed by Marlborough. So Bacon’s posthumous career rested in many ways on his relationships as well as practice. So it seems there is an appetite in the market for artists to be avant-garde hell-raisers, outsiders, etc. I don’t think that Hennessy could ever be seen as a hell-raiser; it just wasn’t his personality. Also, 1980 was too soon to bracket him in as a ‘queer radical’. So there just wasn’t space for him to exist within a biographical framework that reflected the way he lived his life.

RICHARD JOHN JONES:

Retrospectively discussing the sexuality of artists after their deaths is not necessarily a new thing but still something that many people find controversial. I think that people see it as retrospectively outing people, or they sideline it as unimportant, so how did you deal with that accusation and why is it important to discuss that element of Hennessy’s biography?

SEAN KISSANE:

So the question of outing is very interesting because he left instructions, if you will, for himself to be outed. By that I mean he had intended his journals and diaries to be made publicly available after his death. They were donated to the National Library and according to his partner Henry they were extraordinarily scandalous. Those are now ‘lost’ and the thinking is that the diaries were intercepted by someone who was named in them and they never made it to the library. So there is an act of historical erasure there. The point is, when one is forced to live in the closet, one lives in a more careful way. Society didn’t need to know any of Patrick’s or Henry’s business; they are described in public as having a demeanour of ‘two maiden aunts’. So that was a kind of closet that they were situated within. In private we can presume that they were themselves but their relationship or love was never named. So they were as out as they could have been for their period.

RICHARD JOHN JONES:

So I wanted to talk about the coded communication in his painting Self Portrait with Figures (1972). The work depicts a previous painting in tromp l’eoil style of two boys loitering in the Jardin des Tuileries, which was at the time a notorious gay cruising area frequented by male sex workers. Hennessy then paints himself in the foreground of the image with a red scarf, something that has been a signifier of homosexuality since the 1920s. Michael Craig-Martin described the exhibition in which it was shown as ‘the gayest exhibition’ he had ever seen. Yet still in the early 1990s, when the work was acquired by the National Gallery of Ireland, their description of the painting was simply ‘the artist standing in front of a previously completed canvas’.

SEAN KISSANE:

This is the perfect example of codes only being legible to those who can read them. Each of the signifiers you list is specific to queer culture and the painting functions in an entirely different way within and without that milieu.

Richard John Jones:

So in terms of discretion, by not openly declaring anything but leaving clues, this is clearly a way of navigating the particular moment in which he lives, but what do you think he’s doing that for?

SEAN KISSANE:

Hennessy is choosing to paint certain social and political events. Now, you might not consider Self Portrait With Figures a representation of a social and political event but if you do, then that’s a form of activism.

Richard John Jones:

So would you suggest that art can then operate in a way where it’s not necessary to disclose an exact position of an artist in relation to the subject matter. It opens a space in which one can describe political and social situations without needing to name them?

SEAN KISSANE:

In Ireland historically you could largely do what you like as long as you didn’t ‘name’ it. It is a part of the culture of colonization where it’s impossible to function within a colonial context by speaking the truth because you might be killed for it. Irish people had to learn methods of obfuscation and saying what you mean in different ways. Part of the narrative of the exhibition was connecting the colonial and queer experiences because both had to do with a male identity that was other. There is a tradition that if something is subversive, you do not name it out of an act of self-preservation. There is a flip side to that, though, in the sense that it allows a space for a very certain kind of creative ‘freedom’.

Richard John Jones:

Maybe that’s the significance of what art can do in this conversation, though.

SEAN KISSANE:

I’m drawn to Hennessy’s paintings of the lonely men with their backs to you in the Irish landscape. They are subtle and not even coded but they depict loneliness and isolation and we are left to imagine the significance of that in various contexts. It could be named (as queer) but their power is in their universality. In the context of Irish art, remember, the narrative that we are given is through Seán Keating and the nationalist school of painters that are depicting the heroic soldiers of the War of Independence. This reflects the need to recover the image of the Irish man after having been crushed by 700 years of colonial experience. Hennessy shows us a different kind of Irishman and that’s very important.

fig 6:

Party magazine was for real men

Published from the mid-1970s to the mid 1980s, Party magazine could be found on kiosks anywhere around Spain. To most it looked like any other trashy pop-culture pin-up rag. It featured topless photo shoots, reviews of erotic film festivals, city guides

and sensational interviews and was always topped off by a luscious glamour model on the cover. It was, like many other magazines of its time, aimed at a mass market and printed to generate as much cash as it could. However, there was something just a little bit different about Party. Realizing there was untapped market potential in a homosexual audience but restricted by the strict censorship laws under Franco, The Godó Group, which was the major publishing company that secretly funded Party, came up with a discreet compromise. Party was to masquerade as an adult magazine for straight men but contain additional content aimed specifically at a burgeoning gay audience. It is perhaps unrivalled as the most mainstream form of covert mass-communication in such a highly oppressive context.

Nestled in between its standard content were naked photo shoots of male models, drag queens, gay city guides and serious information about the advances of the gay rights movement. Its personals section, a similar exercise in discretion, were invaluable to building connections and community in a repressive world. Party is indicative of how there are hierarchies and layers when it comes to discretion. The world of adult magazines provided the perfect cover, a language that was already somewhat underground but thankfully not illegal; it was the perfect medium through which to communicate something that, at the time, simply couldn’t be named. Party is a reminder that in trash culture we are often to find gems of cultural expression, movements yet to come and political changes that would change the lives of so many. Needless to say, now Party only survives thanks to private collectors and, through donation, is now preserved in the Casal Lambda gay association in Barcelona.