Since Yoshiharu Tsukamoto and Momoyo Kaijima founded the Tokyo based architecture firm Atelier Bow-Wow in 1998, they have become well-known for an incredibly diverse oeuvre of architecture that ranges from houses to temporary moving structures to large public buildings and public spaces. As they work in a simple multi-level structure in which they also live, they keep their team intentionally small – between 8 to 12 people.

Outside Japan, Yoshi and Momoyo first gained recognition with their publication Pet Architecture (2002) – a term they coined for buildings that were squeezed into leftover spaces. Their fascination with simple yet revealing everyday elements such as drainage and air-conditioning units was continued in the book Behaviorology (2010), a study on the relationship between our behavior and the spatial environments we live in.

Over the past years David van der Leer spoke regularly with Yoshi and Momoyo while jointly developing a series of architectural structures in New York, Berlin, and Mumbai, often at odd times of the day, and about topics that went beyond the mere design project.

Speaking between Tokyo (11.00 pm) and New York City (10.00 am), over Skype, they talk about eroticism in architecture and cities, a topic none of them felt comfortable with bringing up in their discussions before.

David: How nice to see you both again! It has been a while, and, Momoyo, you are not wearing your Yankee’s t-shirt today?

All: (Laughter)

Yoshi: She’s chic today.

David: Very chic.

David: Good. We are speaking about eroticism today, and I thought we could start this conversation by focusing on your houses. After all when working with residential clients, you must get involved in very intimate stories. How do you deal with the most intimate requests?

Yoshi: Intimacy is a space that we as architects have to agree on with the people we work for. A good personal space truly reflects their desires, even though they are not always aware of these desires. For that reason, designing the space of a house can become a very intimate relationship. Together we try to establish a framework to proof their lifestyle, so to say. Or better, to proof the client’s way of life. Sometimes we work with people who are suffering from their lives in ordinary buildings. They simply do not fit in with conventional residential frameworks, and it makes them feel like they are wrong, they are somehow making mistakes, they are behaving in a bad way, that their lifestyle is not so sophisticated. But the framework that these spaces generate is usually the real problem, and not the client. These particular people are often very sophisticated, yet they do not know it. We are very interested in defining better frameworks for these people who want to behave in very specific ways in their personal spaces.

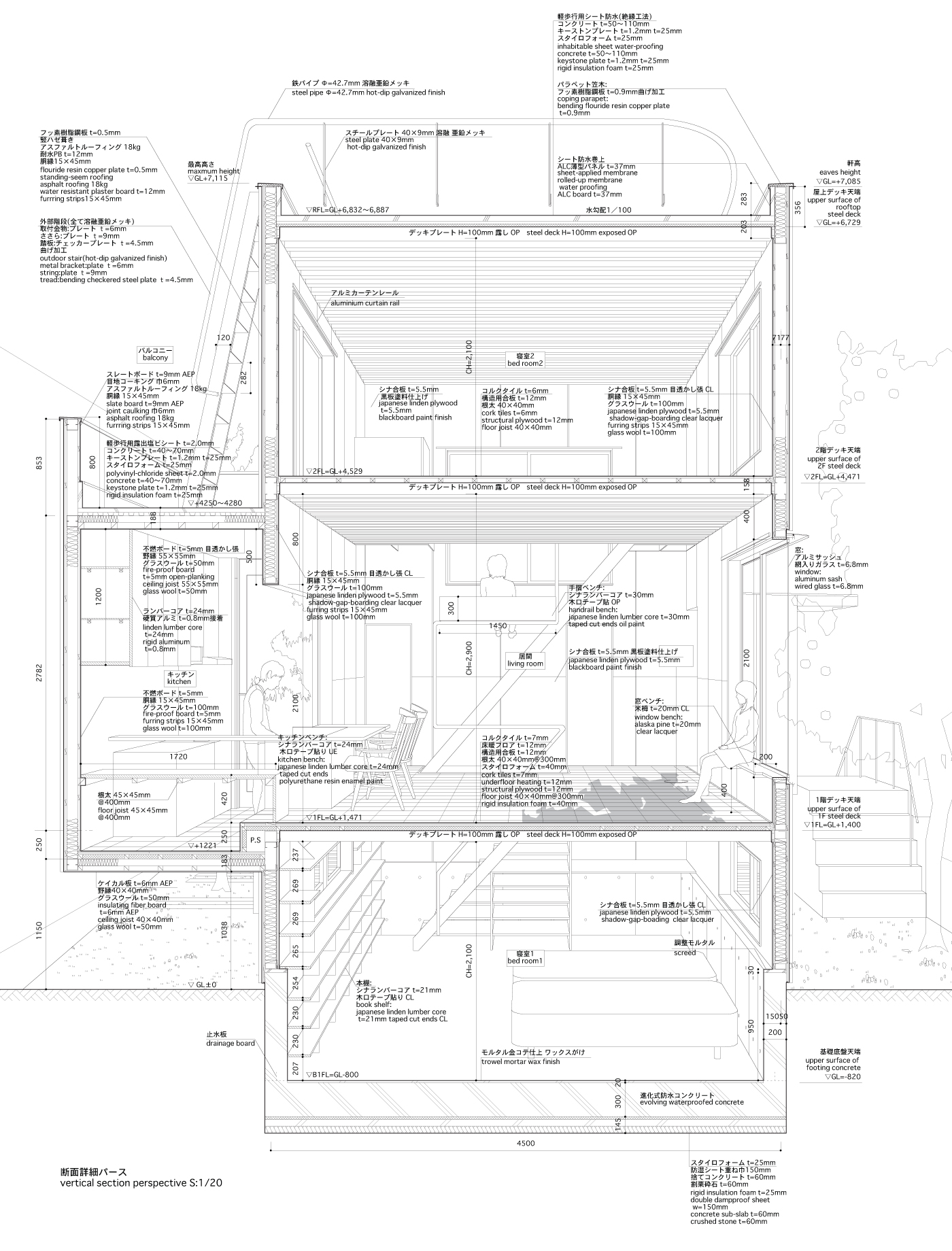

Mini house, drawing: Atelier Bow-Wow

David: Could you give an example?

Yoshi: Yes, for instance during the discussion with people we work for, we go down to seemingly silly details like how they prefer to dry their laundry.

David: Laundry? Ha-ha. That was not necessarily the type of intimacy I was thinking of, but please go on.

Yoshi: Some people prefer a pole, some people prefer pins, some people prefer hanging it outside on the terrace, and others prefer keeping it inside. It all depends on the lifestyle and upbringing the client experienced before coming to us. It is very important to adapt and to approach the client slowly when designing these simple everyday elements for them. This is when the architecture is getting closer, step-by-step, toward the client.

Imagine a house for a mistress. But the client didn’t really talks about the existence of this mistress, and then we have to guess. That’s really nice…

David: Beyond their laundry there must be odd things that people are not comfortable talking about. I wonder what little tricks you use to pull this type of sensitive information out of people. Laundry is one thing, but perhaps people decide to sleep in separate bedrooms after they have been married for 25 years and so on. Those things can be rather awkward in a conversation, how do you deal with that?

Yoshi: It is usually very open. We just ask them, ‘How do you sleep? Do you sleep together, or do you sleep separately, etc.?’ So the conversation is very open.

Momoyo: These are not personal questions; it is just about the way they live.

Yoshi: It is personal.

Momoyo: Okay. It may be personal, but we are not so curious about the person, but more about their life and their lifestyle. So we may ask them, how many closets do you have, or how many shoes do you have, or how many books do you have? Of course, we could ask them personal questions, but intentionally we don’t ask what kinds of books they have. We are just interested in the number of books. We are there to streamline their lives. For example, think of the kind of storage space you need for skis or hiking boots that you usually only use on weekends. You don’t want them to stand in the living room, nor do you want to keep these on the third floor. Imagine lugging the golf clubs down every weekend. That would be too much work. This streamlining of life, or streamlining of lifestyle, is very important, yet we respect our client’s privacy.

Yoshi: However strange it may sound, sometimes you want your personal space to be a territory where you can be anonymous. In our minds it is an important releasing aspect of a house, and of house design. If the house design addresses too much of your personality, your career, or your desires, it can be very annoying.

Momoyo: It would become too embarrassing to show others… I think a lot of our clients want a framework for their lifestyle, but simultaneously they believe their lifestyle is not special enough for a framework.

Yoshi: Lifestyle is a sort of style, and for that reason it shouldn’t be monopolized by a single individual. I think a house should go beyond the territory of each individual. We don’t believe architecture or design can make a single personality tangible. But architecture and design can deal effectively with intangible things.

David: Interesting. Did you ever run into erotic issues that you couldn’t discuss with your clients? Did you ever have clients that did not want to say how they would really be using the house? I can imagine juicy cases with secret lovers and prostitutes.

Yoshi: I would love to meet these clients! Imagine a house for a mistress. But the client didn’t really talk about the existence of this mistress, and then we have to guess. That’s really nice… interesting.

Momoyo: Would that really be a dream house for you?

Yoshi: I would keep parts of the house very open to the public, open to the neighbors, rather than creating a space that is completely sealed off from the street. Imagine a house that at times is porous to the neighbors, or non-family members, but that also has hidden corridors; mysterious buildings like that are always very interesting. For the Japanese today there is a renewed kind of participation of the individual in the public realm, and this personal porosity relays a sense of eroticism. Being asked to design a house like that could be an interesting exercise in trying to violate the boundaries of one’s skin: a topic we have been very invested in over the past years.

David: Ha, before you go on about that house, please tell me more about personal porosity. Aren’t the Japanese incredibly protective of their privacy?

Yoshi: Yes, but things are changing. I think it’s very different from the 1970s. In the 1970s, the establishment of the new skin, based on modern ideas of privacy, was quite fascinating for architects, because, I assume, it touched the sense of eroticism of that moment. Being private originally meant a lack of ability to participate in public, but during this period privacy was rediscovered as a positive hideout of sorts from society. Boundaries were transformed, and the ‘private’ was redefined as something fashionable and cool. Today we seem to wonder if boundaries and the skin can be responsive and expandable, or even have absorptive qualities. We experiment with the extent to which we are willing to accept violations of the fixed idea of the borderline, or the skin of one’s territory. And if we speak about eroticism in architecture, this reinterpretation of the borderline, of the skin, in my mind should be considered more essential.

David: Can you give me an example, Yoshi?

Yoshi: Have you seen the film, A Man and A Woman by Claude Lelouche? … (Humming a song)… There is a very famous song in that movie that you may know…

Momoyo: (Laughter) This film from 1966 is about privacy, about people trying to escape status patterns. It is about escaping from family or community ties; about the thrill of the escape; about the power of being among other people in public.

Yoshi: Until recently, privacy had become too materialized and formalized in architectural planning, but I have the feeling people are getting very bored with these hard skins. People are getting more interested again in opening up. They want to make the skin more responsive to the outside world and create a new permeability between inside and outside. This is very erotic, in a sense.

David: This makes me think of your set-up in Tokyo. There you have created an incredibly porous border between your office spaces and your personal living spaces. Is this because of its erotic value? You made a very intentional design decision to give up your privacy almost completely.

Yoshi: No, we still have a sense of privacy because of our work schedules. For example, we don’t work during weekends, so then no staff is in the office. At those times the entire building becomes a private living space for only the two of us. So it’s very okay and we feel lucky because then we use the entire place.

David: So you try all the desks on Sunday?

Yoshi/Momoyo: (Laughter)

Yoshi: We enjoy experiencing many different modes of space in that same building. It is quite comfortable, because it is the space that is changing rather than us having to move constantly. We don’t need to move to change the mode of the space, but the space itself changes depending on the time of day or on the day of the week.

David: Let’s jump back to what you said about the skin, and the relationship between the 1970s and now. Imagine it is 2050; do you think we are looking at a completely different way of building homes then? Especially in the light of this new sense of porous privacy related to eroticism?

Yoshi: In order to explain I think we should stay with the 1970s first. This extreme privacy of that time that I was describing was clearly reflected in Japanese house design. The best examples are Toyo Ito’s White U, and Tadao Ando’s Sumiyoshi Townhouse. They designed houses that were as closed off as possible, and while doing so they created the beautiful interior spaces that we have all come to love.

Momoyo: But of course it really was all about escaping the urban interruptions, because at that moment even in the residential areas of Tokyo the air was so polluted and it was so stressful that they wanted to create silence for their clients’ personal lives. So they designed these boxed-off living spaces.

Yoshi: I don’t think it was only a reaction to the urban environment. It was also about a shift in mentality. In the 1970s modernization brought individuality, and even though individuality cannot be misunderstood for privacy, people were eager to know what privacy was and how one could be more private. Privacy was thought of in a fairly conventional and confused manner. It was largely misunderstood during this period, and architecture and design were heavily impacted by this shift in society.

Momoyo: During this time the Japanese believed their personal borders were identical to the strict borders architects were promoting. But twenty years later we, at Atelier Bow-Wow, began trying to extend or alter these borders of architecture and by doing so alter the borders of perception. From the moment we started working together in the 1990s we tried to redefine the potential of gap spaces between buildings. We were looking for a new type of porosity.

David: What I find interesting about Japanese society is the paradox of the private. You describe things being closed off, but then on the other hand you get these vending machines in semi-public spaces where you can buy the pantyhose of 16-year-old girls. To an outsider this way of dealing with sexuality is very bizarre. Are you describing a society that is becoming much more open? So there may not be a need for those vending machines in the future?

Yoshi: It is difficult to explain, but I think this kind of behavior probably all dates back from the 250 year long Edo period. During these centuries the monarchy was not at war and as a result the only thing the Samurai had to do was make sure not to get bored and maintain their status.

Momoyo: –by physical exercise and study–

Yoshi: –and then during this period, especially during the last century of the Edo period, there was a new sense of, how do you say… Sexuality. They had a kind of boy’s love, for example, and they developed pornography. It is during this last century that sexuality and a new exploration of eroticism really started to blossom.

Momoyo: Some of the subcultures we know now, like Manga, or Ukioye, or Habuki, find their origin during this time, and perhaps we can date the behavior that asks for these vending machines also to this period.

David: Interesting, but it still doesn’t explain me how these pantyhose vending machines exist alongside these slowly diminishing trends of privacy. Would there be another way to rationalize this?

Yoshi: Yes. There is a strong tendency, or mentality, in Japanese culture to subdivide things into the smallest possible elements. So if you understand something as A and B, people start thinking, there must be something between A and B. Which must be C. And then, if you have A and C and B, people start thinking about what is between A and C and B, and get to D. This happens in all different parts of our culture: we subdivide, and strive for detail. For example, in the organization of the city, we have a very strong concept of front and back. But once the front and backside of, for instance, a building, are established by the architects and builders, the occupants and the people on the street will most likely identify another front and back on the back, for example…

…the intangible allows us to share with others

Kadoya 315, a commercial and residential complex.

it is exactly that sharing, that to Yoshi and me can become erotic…

David: (Laughter) Yes… ?

Yoshi: And then, within this back of the back, people start again finding another front and backside, and this subdivision is constantly developing, until finally, the first front and the very last backside become very close to each other. Don’t get me wrong. This is not all perception. Sometimes you can even see these adjacencies. For example, once a building gets demolished, you may suddenly see clearly there is a back and a back, and a backside. But then on this backside, of the backside, of the backside, you find the new front side of the building.

I see that you think I am avoiding answering your question… (laughter) but actually this subdivision process is also key to understanding eroticism in our society here in Japan. I feel the openness of eroticism, as you see in the pantyhose vending machines, has somehow gotten accepted in the list of endless different subdivisions of sexuality.

David: Um hmm.

Momoyo: If it’s only one odd fetish like this particular one with the pantyhose, people may have difficulties to accept it, but if there are so many variations, one of them can be okay. It is at the back, of the back, of the back, but suddenly it can reach the front again: such as with questions like yours.

David: Right.

Yoshi: So in the end everything balances out. I think these pantyhose vending machines, and also many other parts of eroticism in Japanese society, are somehow consistently produced through this unconscious but very consistent process of subdivision.

David: Ha, now I get it! Interesting, can we also apply this subdivision process to your Miyashita Park for instance?

Yoshi: I hadn’t thought of that, but probably yes.

David: I like the little erotic moments in urban space, and wonder how you, as designers, can provide a platform for those. During the design process of a project such as this park do you ever think about what it means to be twenty years old and walk through the space and to see a very cute girl or nice guy and to flirt with them?

Yoshi: Ah, I see… okay, okay. I see. Ah, okay, this is quite interesting, yes…

Momoyo: No, we didn’t really make that a part of the design process.

Yoshi: But for example, the space around the Seine in Paris is a well-done platform for these intuitive moments of flirtation. When you pass through Paris from Montmartre to Saint-Germain-des-Prés, you start in this very densely built-up area, which changes from medieval to Baroque, and when you finally reach the Seine under the wide-open skies, with the many monumental buildings along its riverbanks, and the very long sight lines, you suddenly get this very strong sense of being larger than life. You are part of an excellent urban space. It is a moment when people feel like they are bigger than they really are, and that intuitive experience encourages people to perform in more erotic ways: so I believe that in these types of space people flirt more. It is important for us architects and planners to create these types of moments in which people feel like their existence is larger than their physical skin.

BMW Guggenheim Lab Mumbai, part urban think tank, part community center.

Photo: UnCommonSense Courtesy: Atelier Bow-Wow

David: Ah …

Yoshi: Along these riverbanks in Paris you feel you are part of the city’s history, part of a society. It pummels you into this feeling of appreciation for the moments of excellence in human history, and these moments can also be very erotic.

Momoyo: There was a park, near the Olympic Gymnasium here in Tokyo, that until the mid-1990s was often frequented by dancers, performers, and musicians.

Yoshi: The beauty of this place was that people, who participated in this public space, shared certain kinds of behavior. It was a space where people would learn and teach each other how to behave in a place. You would give something, and you would take something from others. This mutual exchange makes one feel very independent and responsible, and it really encouraged people to participate and go beyond the usual aspects of their daily life. Also here, just as in Paris, we often felt: ‘I can go beyond my skin.’ And that is such a beautiful moment when you suddenly realize: ‘I am out of my skin now.’ In my mind that is much more erotic than the usual things people think about when they speak about eroticism.

David: A last question: what in your mind is probably the most erotic thing you can think about architecture?

Yoshi: Dealing with the intangible sphere is the most erotic for us. Whether it is in the design of our houses or of public spaces, the most important and the most interesting and erotic part is the intangible: the elements that we share amongst each other. We like the aspects of spatial experiences that are not completely monopolized by the individual and that are not pre-programmed by the system or administrations yet. If these materialize in architectural form, they are called typologies, and if it’s about culture, they become lifestyles, but that is often already too predetermined. We are interested in the kind of repetitive and sprouting energies that comes out of the interactions between people.

Momoyo: If things are too tangible, and you really feel you can keep them contained in whatever type of territory, it is not something you can truly share with others, but the intangible allows us to share with others, and it is exactly that sharing, that to Yoshi and me can become erotic.