Armen Avanessian is one of the most curious people I know, and also just neurotic enough for a professional thinker. We’ve known each other since we were twenty-somethings living in London, trying (and mostly failing) to be the grown-ups we thought we should be. Fifteen years later and we have both left the city – I for Paris, he for Berlin – and we now have most of the trappings of the proverbial adult: the bills and the nuclear family. Our babies were born not long after one another, and these days our communication includes regular pictorial updates on what the two marvels are up to. Come to think of it, I probably have more photos on my phone of Armen’s son than any other person bar my own daughter. Interviewing a friend can be odd, playing the professional. But Armen makes it easy. The hours we spend talking about his work help me understand not just what ‘speculative’ can mean when applied to philosophy, but also why ‘intimacy’ might be a valid alternative to love.

Anja Aronowsky Cronberg and Armen Avanessian together at the Volksbühne in Berlin, where Avanessian has been producing an ongoing program of talks titled Armen Avanessian and Enemies.

Courtesy: Anja Aronowsky Cronberg

Anja Aronowsky Cronberg: It’s a curious experience this – going from chatting as friends do or Whatsapping baby pictures to interviewing you about your work. Speculative philosophy is quite some way away from the fashion theory I deal with in my own work. I had a lot of reading up to do! In my research about Armen the Professional Ponderer, I kept coming up against unfamiliar expressions. Why are you so fond of the term ‘speculative’?

Armen Avanessian: Xeno-architecture, speculative poetics, post-contemporary, time complex – those are all terms I invented myself or in collaboration with others. What they all have in common is the speculative element. Speculation for me means that you try, in some way, to escape the present. Thinking only within the present makes you stable: you can be critical because you know where you stand; you know where the limits are. The word ‘critic’ actually comes from krinein, which means to separate. When you speculate, on the other hand, the presumption is that you’re doing so from a place with no safe ground: the connotations are often quite pejorative. It is absolutely necessary in times like ours – when we feel suffocated by the present. Speculation for me is a way to think the future but also to think from the future backwards about the present. I use ‘speculative temporality’ and ‘ethno-futurism’ to denote a different way of thinking about time. We’re used to thinking chronologically about time – that one thing happens before the next. Let’s imagine that the future happens first and impacts the present. I’ve analysed it sociologically, economically, culturally, and within language philosophy – that’s why I keep inventing new terms. We are often under the assumption that we share one present – you and me, now – and that we can shape the future. But that isn’t true anymore. Today we live in a ‘time complex society’ – that’s another concept I invented – and we’re not at all in the same present. We live asynchronously. That means that for the first time in human history we live in a society that doesn’t just have human players: there are AI, there are computers, there are algorithm. Algorithms are a good example as they know things about the future and about ourselves that we do not know yet. As consumers we are pre-emptive personalities. And as we all know by now, algorithms can govern us because of it.

I’m talking about something much stronger. I’m talking about the future deciding the present.

Anja: So we continue to labour under the pretence that we can still have an impact on future outcomes. How exactly does our time complex society affect us?

Armen: Speculative temporality is made possible because of digitalisation. We employ pre-emptive policing and wars already; we have proactive medicine providing cures for diseases we don’t yet have; and pre-mediation sees the media become more and more obsessed with what will happen next rather than what has already happened. These are all ways that the future precedes the present and develops the capacity to govern us. Think of our derivative economy or of high frequency trading: these are temporalities completely beyond the human horizon where the future happens before the present. The film Minority Report (2002) is adapted from Philip K. Dick’s eponymous 1956 short story and directed by Steven Spielberg. Set in the future, Tom Cruise is the chief of the PreCrime police department, which apprehends criminals before they’ve committed crimes. Murderers are put away or disposed of – but the problem of course is that none of them have actually killed anyone yet. So I’m not talking about how decisions we make about the future have an impact on how we act in the present – I’m taking a mortgage and I’m going to live frugally to pay it off. This we’re used to. I’m talking about something much stronger. I’m talking about the future deciding the present.

Philip Kindred Dick (1928–1982) was an American novelist, short story writer, essayist and philosopher whose published works mainly belong to the genre of science fiction. The novel The Man in the High Castle bridged the genres of alternate history and science fiction, earning him a Hugo Award for Best Novel in 1963.

In addition to forty-four published novels, Dick wrote approximately 121 short stories, most of which appeared in science fiction magazines during his lifetime. Although Dick spent most of his career as a writer in near-poverty, eleven popular films based on his works have been produced, including Blade Runner,Total Recall, A Scanner Darkly, Minority Report, Paycheck, Next, and The Adjustment Bureau. In 2007, Dick became the first science fiction writer to be included in the Library of America series.

Anja: In the fashion business, thinking about consumer behaviour in this way is obviously extremely significant. In my own work I about how to bridge theory and practice. To what extent can I work in tandem with the fashion industry but also observe and reflect on it and on my own role? How you’ve shaped your role as a theorist seems somewhat similar in this respect – your work often appears indistinguishable from an artist’s. Considering how important speculation is to you, do you still think it’s necessary for you as a philosopher to critique or judge the world around you?

Armen: The dominant mode in the theory world is judging or critiquing: you’re supposed to be critical, not speculative. You judge, you don’t affirm. It’s a dogma or an ideology and it can seem as if there’s no alternative. But if you want to change things, you have to be in them. You have to douse yourself. You can’t pretend that just because you’re on a tenure track in the philosophy department at some university in a European social democracy, you are somehow not participating in neoliberalism. Right?

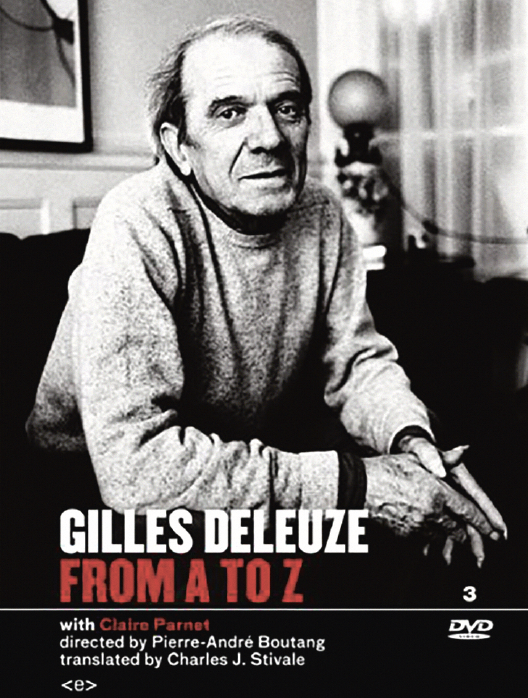

Although Gilles Deleuze never wanted a film to be made about him, he agreed to Claire Parnet’s proposal to film a series of conversations in which each letter of the alphabet would evoke a word: from A (as in Animal) to Z (as in Zigzag). In dialogue with Parnet (a journalist and former student of Deleuze), the philosopher exhibited the modest and thrilling transparency that his seminal works (such as Anti-Oedipus and A Thousand Plateaus) reveal.

The sessions were taped when Deleuze was already terminally ill; he and Parnet agreed that the film would not be shown publicly until after his death. The awareness of mortality floats through the dialogues, making them not just intellectually stimulating but also emotionally engaging. Because Parnet knew Deleuze so well, she was able to draw him out – as no one else had – to what might be the 1001st plateau: a place of brilliance, rigor and charm. In ‘A as in Animal,’ for example, Deleuze vents his hatred of pets: ‘A bark,’ he declares, ‘really seems to me the stupidest cry’. Instead, he praises the tick. ‘…In a nature teeming with life, [the tick] extracts three things:’ light, smell, and touch. This, he claims, in a sense is philosophy. ‘And that is your life’s dream?’ Parnet wryly asks. ‘That’s what constitutes a world,’ he replies. For Deleuze, doing philosophy meant not just creating concepts but living

a life in philosophy.

Anja: Well that’s what I’ve come to understand more and more myself. Increasingly education is run like a business, for example, and this of course affects how research is done. As a research fellow at a British university, I can see that in my own immediate surroundings. Considering, then, being ‘in it,’ in what way is how you do philosophy different?

Armen: It’s a question of habit. Traditional philosophers have a completely different way of working. If you write a book every five years, which then has to be approved by other experts you just don’t understand how someone can write two or three books a year, and edit five. I try to see theory as a form of practice, and use it to understand how the culture I function in works. I’m not trying to preach it, change it or even understand it from the outside. I try to be inside it and see, from that vantage point, what the attention economy we now inhabit is all about. What are the relevant tools of communication now? Why, for example, does fashion have fashion weeks, and why are there a certain amount per year? What does that do to the people who work in fashion and how does this all influence other cultural spheres? And what does that mean for the production of concepts for instance? So for people who grew up thinking that philosophy is the opposite of fashion, because fashion is neoliberal, superficial, about selling out and therefore evil, my interest and engagement in it seems incomprehensible. But you have to remember that for the past 2,500 years of history of philosophy, most of the interesting philosophers weren’t actually academics. They were teaching princesses or hanging out in market places or travelling a lot or whatever.

Anja: Is traditional philosophy still relevant in contemporary culture then?

Armen: Well, of course as a philosopher I like reading and writing long books. But I have to acknowledge that the audience for those kind of books isn’t there anymore – even my own attention span reflects that. So I have two options. Either I get alienated and resentful and say the world is evil, philosophy is no longer possible and everyone is a sell-out, or I attempt to reinvent what Gilles Deleuze said about philosophy: that it’s the invention of concepts. Hasn’t philosophy always adapted to its time? Hasn’t it always had to contend with whatever was fashionable at any given moment? I ask myself: What does it mean to communicate with young art students or people in fashion today? What kind of language or mode of communication would reach them? I’m not saying that my way of working is the only, or even the right, way. I’m trying things out.

All I’m saying is that I’m standing in the wind, trying to get a sense of where it’s blowing.

Anja: But at what point have you moved so far from the canon that its tenets cease to apply? Are you still a philosopher if your work is presented in a museum or a theatre or on a screen?

To paraphrase Godard, we need less politics in film and more political films. We need less philosophy in art, and more actual thinking about the relationship between art and philosophy.

Armen: Actually, it’s interesting to me that you refer to me as a ‘philosopher’ rather than a ‘literary theorist,’ which I am as well. Having a philosopher in a magazine like this one is appealing, I can see that. But what I do is often closer to theory than philosophy. Theory is a fairly new concept; as I’m referring to it now it’s a phenomenon that started in the 1960s. A theory book typically comes in paperback: it’s critical, it wants to have an impact on society, it wants to effect change. Theory is related to the everyday. You would never find someone like Slavoj Žižek, Jacques Derrida or Judith Butler in a philosophy department – the people employed by conventional philosophy departments would never be interviewed by you, for this journal. Interesting philosophers today don’t find jobs in university philosophy departments; they work elsewhere. The art world makes great use of philosophers today, for example, since Marcel Duchamp instigated post-conceptualism, which needs theory to buttress it. Every art student today needs concepts and theory to back up the sculpture or whatever they’re making. So as a theorist I ask myself what the art world wants from me and why. They might want someone to write a catalogue text for an artist, but that is intellectual jewellery and not what I do. I would instead propose a collaboration with the artist – that to me is interesting. I’m all for finding new ways of working together, but what you won’t get from me is a text that increases the value of an artist by saying that they are so anti-capitalist or whatever. Catalogue texts are stupid. Why do we need philosophers to write about artists or explain artworks? Why would I write one when all it does is undermine my position by pretending that I’m engaging in a critical practice, when what I’m actually doing is just playing the part assigned to me by this economy? So what can I do instead? I can’t tell others how to do their jobs, or pretend that everyone in the art market is evil. What I can do is reflect on my own position within the field and try to change the rules that apply to me. When I get asked to write catalogue texts I don’t just say no: I propose something different. That is the way I’ve found to be political. To paraphrase Jean-Luc Godard, we need less politics in film and more political films. We need less philosophy in art, and more actual thinking about the relationship between art and philosophy.

Anja: Yes, it’s nearly impossible to go to an art exhibition without coming across more philosophy references than you can shake a stick at. In fashion you can see the same development actually – designers who want the world to know they think always make sure to throw some theorising into their press texts, and fashion students get their Walter Benjamin, Pierre Bourdieu and Roland Barthes beaten into them. Oh dear. Just look at the footnotes in Vestoj – I’m as guilty as anyone!

Armen: People sometimes accuse me of doing ‘theory fashion.’ But I’m really interested in hypes and fashion because they say something about our times. Our reality now is one of constant hype. In 2015 I made a film with Christopher Roth, Hyperstition, which investigates this idea of fictions becoming real. The word is an amalgamation of ‘hype’ and ‘superstition.’ I play with the idea of fictions that become real. Think of Donald Trump. Think of memes. These are phenomena that are capable of becoming real, though they’re invented. I invent new concepts because I’m collecting data and knowledge and I use these concepts as tools in a speculative way as well. This is very different to a philosopher sitting in front of an object and pondering what it really is. Philosophy used to be about abstracting yourself from the world and the everyday, but for me it’s the other way around. I try to invent conceptual tools and then see if I can make them true.

Anja: Ah yes, this is the Armen Avanessian I know and love – the peren-nial and professed outsider.

Armen: Well yes – as long as you think of the outsider as a happy productive entity in the vein of how Michel Serres wrote about the parasite. Neoliberalism, for example, isn’t just about making money. You can obviously be neoliberal as an academic: in the way your work contract operates, in the way you treat your colleagues, in how you got your job, in what you do to prevent others from getting in and so on. Even if your salary is laughable in comparison to the CEO of Gucci, it doesn’t mean you’re exempt from the underpinnings of our economic system. Don’t get me wrong – I’m not saying that everything is the same or that philosophy and fashion have the same business model. What I’m saying is that money isn’t the only thing that matters when it comes to neoliberalism. Just because philosophers haven’t figured out a way to make good money from what we do, it doesn’t mean we aren’t eager to. I don’t want to make it too easy for myself or others like me. Earning less obviously doesn’t make you ‘better.’ And being an outsider is a mindset.

Anja: Why is it important to be an outsider though? What are you outside of, and why? What do you gain from this positioning? What do you lose?

Armen: I am a white Western male. How can I be an outsider? This has been leveraged against me more than once by white Western women who don’t recognise that I am also an Armenian refugee and a genocide victim. I’m seen as male and therefore as part of the majority, which of course I am. I don’t mean to deny the problems that exist in our hierarchy of power, and I don’t want to deny that I am, in so many ways, in a privileged position. But making assumptions about who is the most privileged is also not always helpful or beneficial. It’s very popular now to identify with a minority group. Everyone is part of a minority. I myself can think of a handful of other minorities I qualify as. But I’m getting tired of this way of seeing the world; I don’t think it’s very productive or progressive. We’re trying to outdo each other, to win the minority battle, and I see a kind of striving to make the minority the majority. A will to power, as Nietzsche would say. Instead what I look to is how do I operate within the field that I’m a part of? I am an outsider in the art world, absolutely. But I’m also an outsider in academia.

So I think about who I work with, the kind of topics I work on. These are areas where I can effect change, not by pretending that I don’t have power in order to gain it.

Anja: I can see how these ideas influence how you think and what you write. But what about your life outside of work? In what way do you live by the concepts that you work with?

Armen: For me it’s not so much that the concepts I work with have an effect on my life but rather that my private life practises my theory. The tools you invent, end up inventing you. Mankind invented computers, and computers invented man. In order to affect change, I propose philosophy as practice; it isn’t something that should only be taught or thought about, it should be practised. The last few books I wrote were written from the point of view of a ‘You’ or an ‘I.’ I don’t believe in an objective author anymore. The author is always there and with a clear point of view. This is theory as life.

Miamification (2017)

Anja: Do you believe in a separation between ‘work’ and ‘life’?

Armen: There is no either/or. These separations are fake. I began Miamification (2017) as a sort of diary; when I realised it was becoming a book it felt right to keep the subjective form. I was academically trained to write objectively, to edit out anything that could be construed as my personal bias. But that isn’t true for how we actually live or work. I don’t believe in these separations: philosophy or life, creative writing or scientific writing. They are just cultural constructions. Think of Descartes: Cogito, ergo sum [I think, therefore I am]. Think of Montaigne, think of Nietzsche, think of Plato. Philosophy has always been a part of life. Didn’t Nietzsche say that most philosophy is just a problem of constipation?

Anja: But how does philosophy come into your own everyday life? Does ‘theory as life’ also affect the people you choose as friends, or the partner you love or how you raise your child?

Armen: I spend my time doing what gives me the most pleasure, and right now that means spending time with my son. Sixteen hours a day, every day? No problem. I make sense of the world through thinking about him now. What does it mean to witness a birth? How is it that philosophers ponder beginnings so often but without ever mentioning giving birth? Well, they were male and didn’t care, right?

Eroticism is slippery and ambiguous which makes it more interesting. Love on the other hand is such a hysterical concept. Love as we understand it today is a cultural invention which plays a certain role in bourgeois society.

Anja: In thinking about theory as life – what else is there but intimacy?

Armen: I’m very interested in intimacy. Consider that intimacy is always something that involves another being – you cannot be intimate with yourself. I hate the discourse around love though. It really bothers me. Our whole society is built around the concept of love, with all its rules and theatrics. Intimacy is much more private and hidden. François Jullien has written on intimacy; he says that it reminds us of the opening of subjectivity itself. It’s co-produced, and it’s a metaphysical reminder of who we are. Think of playing with someone’s hand while watching TV for example. Moments of intimacy remind us of how we come into existence as subjective beings, and what it means to encounter others. In this way it’s a productive moment. Intimacy, eroticism and love are very different concepts actually. Eroticism is slippery and ambiguous, which makes it more interesting to me. Love on the other hand is such a hysterical concept. Love as we understand it today is a cultural invention that plays a certain role in bourgeois society. There’s an aggressiveness to it; it’s possessive and demanding. ‘I love you so you must love me back. If you don’t, I can’t continue loving you.’ It’s very prescriptive and very different to intimacy or eroticism. Intimacy is an interesting proposition to rival the hegemony of love in fact.

Anja: But aren’t they all about the desire for connection?

Armen: The way we define love causes a lot of misery actually. In relationships we’re always checking if the love is still there, or if we’re loved enough and in the right way. I’m interested in less oppressive alternatives. I’m not talking about thought experiments, but rather about gestures to live by. I like the concept of passion as an alternative – Michel Foucault wrote beautifully about this idea. If you’re passionate about someone, you don’t need them to reciprocate. Passion happens to you. Intimacy is a delicate proposition, and one far too little explored. Imagine if ten per cent of books written about love would be written about intimacy instead – what a rich universe that would be. Or if ten per cent of pop songs written about love would be about all the nuances found in our erotic universe – not just the ‘shake your ass’ variety we’re used to.

Anja: Can you tell me a bit more about this distinction you make between love and eroticism?

Armen: I think the way we understand love today is too dogmatic. Even the Greeks had a multitude of ways to identify what we now use the term ‘love’ to encompass: eros, philia, agape, empatheia and so on. Love is a very declarative emotion. It has to be announced – to your beloved, to your friends, to your therapist. The discourse reinforces how we practise the thing itself.

Eroticism for example isn’t actually a feeling, it’s a happening between people. The discourse of feeling isn’t always helpful – feelings are always already laden with cultural connotations.

Anja: But couldn’t ‘love’ just be a catch-all phrase for all of the feelings you mentioned, a term we use for simplicity?

Armen: But they are all different. Eroticism isn’t actually a feeling; it’s a happening between people. The discourse of feeling isn’t always helpful – feelings are always already laden with cultural connotations. I think we would gain a lot from being more open to alternatives to love. I have a real problem with the declarative element of love. I’ve never said, ‘I love you’ to anyone: partly because I’m Austrian and we say ‘Ich habe dich lieb’ rather than ‘Ich liebe dich.’ But I also think the phrase ‘I love you’ is dubious and contaminated. Today we love each other, and two years down the line we hate and sue each other.

Anja: Do you mean to say that emotions should not be verbalised?

Armen: What I mean to say is that feelings are culturally produced or structured. They are not outside of the semiotic. I’m a structuralist on this point: the way a culture frames its concepts has an impact on how they are exercised. It’s not like we have ‘real’ feelings that we misidentify in language. No. There is no such thing as ‘only rhetoric.’ Feelings are shaped by discourse.

Anja: So what role or place do these concepts – love, tenderness, intimacy or eroticism – have in neoliberalism then do you think?

Armen: Well on a very basic level these are notions for the privileged – you need time, which is a luxury today, to encounter other people in order to experience any of the phenomena related to these concepts. But think also of the many industries built around our understanding of love – from Hollywood to the self-care business.

Anja: If you’re loath using the term ‘love,’ how would you instead describe the feeling you have towards your son?

Armen: I’m trying to figure that out. I’m speculating. What I can say is that it’s the most intense, happiness-producing feeling that I know. What does it mean to have intimacy with someone who is obviously incapable of loving me back because he doesn’t even know that he exists as a separate entity yet? I’m trying to use all these experiences and daily routines to practise theory. What does it mean to read poems aloud again? Which rhythms or intonations connect best with this new being? How does it change my own relationship to language to communicate with someone who doesn’t yet speak? I don’t need any answers to these questions; I’m happy exploring. This is not about love between two psychologically mature entities, but it is about intimacy. To say something provocative: it’s far too delicate for love.