Few contemporary filmmakers confound and intrigue like Alain Guiraudie. Since his 2001 debut ‘That Old Dream That Moves’, hailed by Jean-Luc Godard as the best film at Cannes that year, the French director has produced a body of work distinguished as much by a refusal to play by conventional codes of character and storytelling, as it is for its near-documentary attention to environment and matter-of-fact presentation of explicit sex. His protagonists are typically working-class men in the rural areas of southern France, where Guiraudie grew up. Yet their lives – and often sexuality – are anything but predictable.

At fifty-one minutes, That Old Dream That Moves offers a compact introduction to idiosyncratic rhythms of Guiraudie’s cinema. It follows a young man hired to repair a mysterious machine at a decrepit factory in the process of being shut down. As he labours alone each day, he arouses the curiosity of his aimless co-workers. The film appears to unfold as a well-observed portrait of post-industrial malaise. But Guiraudie subtly tweaks the realism, playing gently with allegory and even surrealism, edging the tale into ambiguous territory. When an older married co-worker reveals an intense crush on the young man, Guiraudie uncloaks his favourite theme – the illogic of desire.

Machine specialist Jacques (Pierre Louis-Calixte), That Old Dream that Moves, 2001

The film rarely leaves the confines of the factory, and the director’s careful repetition and variation of shots imbues these spaces with an oneiric quality. It’s a technique he uses to great effect in 2013’s Stranger by the Lake, the director’s acclaimed Hitchcockian thriller that won him international attention. As with his debut, the action unfolds in one location – this time, an idyllic gay cruising area that turns deadly – where twenty-something Franck falls for the mysterious Michel. Each day is a waiting game that rotates around the fulfilment of sexual desire and the thrill of the unknown.

But if those films display Guiraudie’s skill as a filmmaker able to twist audience expectation with clock-like precision, they do little to prepare you for the wild, strange trips of 2009’s The King of Escape and his latest, and arguably his most anarchic, film, Staying Vertical. With these films, the director warps, bends and splices genres with apparent abandon. A single scene may swerve from slapstick to tense drama and back again. The far-fetched plots purposefully flirt with incoherence, and at times feel downright random.

And yet, these strange, rich brews cast a unique spell. They are unlike anything else in modern cinema. In both examples, we follow restless men seeking escape from the banalities of ordinary life. Armand in The King of Escape is a middle-aged gay salesman who initiates a relationship with a young girl and winds up on run from the police. Léo in Staying Vertical is a filmmaker who impulsively decides to have a child with a shepherdess who abandons him. Tethered to his car, he is propelled by some relentless inner momentum that he doesn’t even fully grasp. Staying Vertical is, in the end, a kind of adventure film – albeit one featuring bisexuality, assisted suicide, parenthood, wolves and magical healing plants.

In other words, it’s Guiraudie working on top form. The director sat down for a conversation about some of the themes and ideas buried inside Staying Vertical.

Paul Dallas: Staying Vertical was pro-bably not the follow-up film most people expected from you after Stranger by the Lake. It seems to have more in common with your earlier work like No Rest for the Brave and The King of Escape, episodic films filled with absurdity. I’m always interested in where projects start. What sparked this new film?

Alain Guiraudie: I actually went back into my journals to see where it started, and I found that I began writing it back in January 2013, when I was in the US with Stranger by the Lake. At the time, I was just collecting different ideas. For me, Staying Vertical was inspired by the locations. We filmed in Brittany, in the west and south-west of France, and there are three main locations that we used. The first is a giant limestone plateau that I was drawn to, this broad open space that I wanted to picture very much. I also had a strong desire to film the swamp, the bayou where we find Mirande, the healer living in a cabin. It was another place that called to me to be filmed. And I wanted very much to film the city of Brest. These places were at the foundation of what I wanted to show in the movie.

So when the audiences are shocked by a film’s graphic nature, that’s saying a lot – but French director Alain Guiraudie’s new film, Staying Vertical, manages to achieve just that. The absurd and haunting dark comedy features explicit sex, a close-up long take of childbirth, and other audacious artistic choices certain to polarize audiences. It does take some time to realize that Staying Vertical is a comedy; at first, the film is just perplexing. The characters do not have clear backgrounds or motivations. They simply meet each other; wallow in awkward silence or talk about nothing of significance; and sometimes have sex. By the film’s conclusion, almost every character has had sex with another, with couplings between both the same and the opposite sex, similar age and those much younger or older. However, not a single sex scene is shown as erotic: They seem almost to be taken out of educational videos, and many times, they confuse the audience with regard to why they happen.

This portrayal is in tune with the rest of the film, in which the protagonists’ actions simply occur, leaving little space for empathy or explanation. Courtesy: Tianxing V. Lan, The Harvard Crimson

Paul: You were born in the south of France and live in a small town today. All of your films, beginning with That Old Dream That Moves and up to Staying Vertical, take place in small towns, villages and the countryside. You seem to have a deep connection to these landscapes and there’s an intense quality to the way you capture these remote or overlooked places. I’m particularly interested in what different places inspire you as a filmmaker. What do they suggest to you?

Alain:For me, different locations conjure up certain thematic ideas. For instance, when I think of Corsica, I think of Westerns, because the landscape lends itself to these stories. When I think of the swamps and bayous, I think of a film by Nicholas Ray, like Wind Across the Everglades (1958).

The city of Brest, for example, is very unique in France. It was completely destroyed during the Second World War, and so it’s been entirely rebuilt since then. But it’s been reconstructed in a way that’s not really French. The streets are very straight, and it feels almost American in style. In Staying Vertical, Brest is seen as grey and rainy. I’ve been told by a number of people who saw the film that the city feels cold and hostile to them. It is, after all, in Brest where Léo encounters the homeless man and is later assaulted quite dramatically. But in the film, I really didn’t want to contrast this idea of the countryside as a warm and welcoming, and the city as a place that’s cold and inhospitable. For me, Brest doesn’t feel hostile or cold at all. Perhaps it’s just the way the city has been rebuilt that accounts for this atmosphere.

Homosexual marriage and the whole question of euthanasia is a big issue in the news. Gender theory is also causing a lot of discussion today. These were all in the background as I was writing…

Paul: I’ve never been to Brest, but in the film, the city felt forbidding to me as well. The swamp, by contrast, is a place of sensuality for Léo. It’s where he goes to be healed, or even have sex. Brest, on the other hand, is where he escapes to work (unsuccessfully) on his screenplay and later to steal away with the baby when he’s on the run. He seems so alone there, so maybe the coldness we’re speaking about is more a reflection of an emotional state than of Brest’s architecture. But I wanted to get to some of the ideas that are swirling around in Staying Vertical. For me, the film is very political. I know that you work intuitively, while the film feels like a direct response to a number of social issues people are dealing with right now.

Alain: There are two other elements at the origin of Staying Vertical. In France, a lot has been going on in the news, and there was a vivid public debate over some important issues. Homosexual marriage, for example, has been a very big issue in the news in recent years. Also, the whole question of euthanasia was also important. Gender theory is also causing a lot of discussion today. These were all in the background as I was writing and they filtered into the script in different ways. More specific to me, however, was this question of the wolf. There has been a controversial movement to reintroduce wolves back into nature. While working on the script, I spoke with a number of livestock breeders who were very much opposed to this. I also had a formal reason for making the film. Stranger by the Lake was very rounded and contained. With Staying Vertical, I really wanted to return to the kind of cinema I was making before and that I really love. It’s a cinema that mixes different genres and elements – dreams, reality, daily life, myths, existential questions – and takes all of these things and puts them together.

Paul: Solitude is another theme in your films. Many of your characters are loners, or people following their own idiosyncratic path. Léo in Staying Vertical is a prime example. Wandering through the film, he has a series of encounters with different people. Despite that, Léo often seems quite alone, even after becoming a father. At the end of the film, he has clearly embraced a kind of solitude. But I wanted to ask you about the communion and connection Léo experiences with Mirande, the healer he visits in the swamp. Mirande doesn’t belong to the same world as the other characters.

Alain: In a way, she fits my ideal of what a doctor should be! For me, a doctor is someone who not only treats you physically, in a gentle way, but also takes care of you psychologically – both of these aspects combined. The character of Mirande was really inspired by the environment of the swamp and bayou where she dwells. Her character is part of that space. We see the healer attach these vegetal tendrils to Léo’s body as part of the healing process. It’s all fantasy that I invented. For me, they are really just meant to embody a connection to nature and a link with the cosmos.

Paul: One of the great subjects of cinema is desire. It’s something that you examine in many forms in your films. We often see it emerge in unexpected ways, pushing characters into unknown territory. As viewers, we don’t always understand or relate to the figure’s desire. It’s often a question as to whether the character is blinded by longing. This is true for Franck in Stranger by the Lake, when he falls for a man who could very well be a murderer. It’s also valid for Léo, who seems to crave an array of different people simultaneously. For you, is desire a mysterious force?

Alain: It may be that I desire desire and I love love. I see it as an exploration, in a sense. Broadly speaking, desire is something that really makes the world go round, it’s behind everything. It also makes us move forward and advance. As far as how it functions, I find it intriguing. But I know nothing about how it actually works.

It may be that I desire desire and I love love. I see it as an exploration, in a sense. Broadly speaking, desire is something that really makes the world go round, it’s behind everything.

Paul: I was particularly struck by Léo’s restlessness as an expression of his yearning. He’s constantly moving from place to place and from person to person. The moving landscape we see from his car becomes the film’s central visual motif.

Alain:It’s true: Léo is always on the move. He’s always going from one relationship to another, always in search of the ‘other’. That is really what’s behind it. In a sense, it’s about this dilemma of discovering who the ‘other’ is, and finding the ‘other’. It’s something that all of us are experiencing. Léo also has the unusual situation of being wanted by everyone else, with the exception of Yoan, the young man he pursues in the first scene. So, desire is really a two-sided thing for Léo. He’s constantly searching for the ‘other’ and also running away from him at the same time.

Paul: Otherness as a theme takes different forms in your films, but it is usually related to transgression. The ‘other’ can be a person, a feeling or a force. I’m reminded of your first film, That Old Dream That Moves, where an older married factory worker chases after a young man. Both men are ostensibly straight. A homosexual crush seems out of place in the working-class world depicted in the film. Yet it exists and the two men accept it as part of the world, even if they don’t act on it. I didn’t connect otherness with Léo in the way you’re suggesting. I’m interested in how you define ‘the other’. Is the other the object of desire? Or is it something else?

Alain: Yes, it’s the object of desire. But it’s not that simple, because you have different aspects. There is the side of desire that’s absolutely fascinating, and the aspect that’s absolutely repellent. This oscillation between fascination and repulsion is something that’s very important. In Staying Vertical, the ‘other’ is really epitomized by the figure of the wolf. For us, the wolf is undeniably the ‘other’. And, of course, the baby is another ‘other’ in the film.

Paul: It’s intriguing to think of the wolf and baby as having this in common. The wolf is an ‘other’ as it’s not human, and because humans treat it as a pariah. The baby is an ‘other’ because it is unformed and vulnerable. Do you see the wolf and the baby as ‘other’ because they exist outside a normalized social system?

Alain:I’m not sure. Perhaps the film gives us the impression that they occupy a similar place because in the film we see them on the plateaus, amidst vast expanses of space. But I think any relationship is unique and different in its own way.

Paul: Next to the notion of the ‘other’, the question of aging seems very important to you. Cross-generational relationships, especially sexual ones, are a recurring subject. Many filmmakers shy away from it, probably for fear of making audiences uncomfortable. But I appreciate that you make us think about desire occurring across all parts of life. Perhaps Staying Vertical pushes this exploration of age and desire to its logical conclusion. Marcel, the old man, dies by assisted suicide while getting fucked by Léo at the climax of the film.

Alain: One of the things I wanted to do in Staying Vertical is to represent people from every different age group, from the newborn baby to the old man on his deathbed. Every character is experiencing life at a different moment. This is an existential film. It deals with the mystery of existence. I didn’t sit down and consciously organize the film to include a baby, a teenager, a middle-aged man, and an old man. It’s something that I did on a more intuitive level. I think, however, that each of the different characters has something of me in them. You see small reflections, here and there. There was probably a time when I was sitting beside a country road like Marcel, listening to music and watching cars pass by. As far as dealing with the question of euthanasia and assisted suicide, I think that the way we approach it here in this film is unique. Perhaps in the end, it’s not the worst way to go!

Paul: The euthanasia-sex scene is something I’ve certainly never seen before! But for me, the most compelling aspect of the film is this mystery of desire. As you said, it’s what makes the world go round. Perhaps desire itself is the ‘other’. In Staying Vertical, desire seems to represent freedom. It’s a force liberated from society’s constraints. It possesses Léo in ways he couldn’t have imagined. Léo desires both men and women, young and old. Most radically, the film challenges the idea of what a family is, and maybe what love even means.

Alain:I wanted to present a different view of the world. There are a lot of questions being explored right now in France and in Western society in general. What does it mean to be a man? And what does it mean to be a woman? Who raises a child? What is it to be a family? All of these issues are important. With Staying Vertical, I wanted to present a very individual and particular view. Like all of us, my idea of family was based on my own. I had a mother, a father, a brother, a sister, and four grandparents. Over time, the concept has changed a lot. Today, we see so many different types of families. Among people I know, there is a husband and wife who are a couple but choose not to live together. Or you have families where the father’s role has changed entirely. Now, most fathers want to be present at the birth of their child. They want to play an active role in bringing up the child. Also the role of the mother has changed, because we’ve come to recognize that not every woman wants that traditional maternal role. What I show in the film is one idea of family, and it’s not necessarily one I’m absolutely attached to, either.

Paul: Staying Vertical is your first film with a protagonist who is a filmmaker. Léo’s twin goals to make a film and to become a father seem to be intertwined. Both endeavours are fuelled by a creative urge. One could argue about which is the more selfish or selfless pursuit – art or parenthood. But I’m more interested in their similarities. At a certain point in the film, Léo abandons the film project, after literally running away from his producer while visiting Mirande. Fatherhood then becomes his main creative ambition. I wondered if you ever wanted children.

Alain:I don’t have any children. I like them, but I don’t have any particular desire to have children. I think that when you’re seriously committed to making films, it’s not something that becomes important to you. People often have children as a way to survive beyond our own lives. It’s a way of achieving immortality. In this sense, making films serves this purpose for me, perhaps, as cinema can also be a way to be immortal, I suppose.

Paul: For me, Staying Vertical is close in form and spirit to The King of Escape. They could almost be companion pieces, or brother and sister. They are adventure films about men seeking escape.

Alain:You’re the first who’s made that connection. I’m really glad you did because I wanted to return to making that kind of film. Perhaps The King of Escape could also be the title of Staying Vertical, but it wouldn’t work the other way around! For me, the real connection between them is in their form. I’m attracted to this idea of making a film that is a kind of ‘mess’ of different tones and genres. In The King of Escape, I was playing with contrasting drama and comedy, dream and reality, daily life and adventure. I wanted to return to this in Staying Vertical, but also go beyond what that film had done. It has greater narrative freedom.

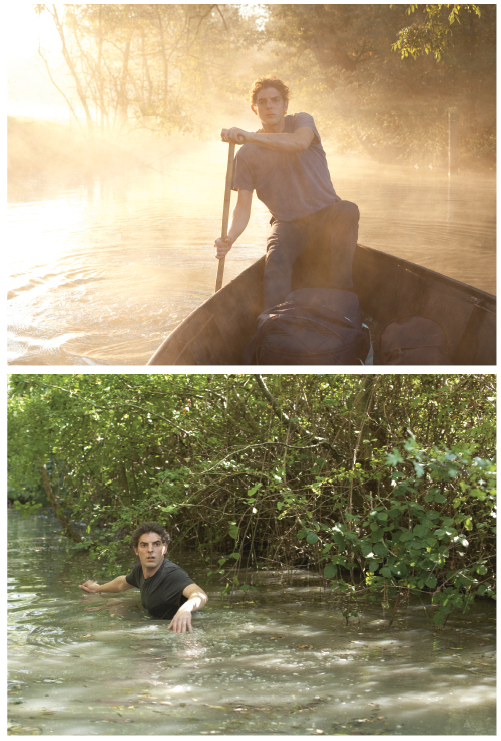

Stranger by the Lake, 2013 Courtesy film still; Wild Bunch

Paul: When we spoke back in 2013 about Stranger by the Lake, I asked you about nostalgia. That film is set in the present day but feels more like a dream or memory of the 1970s. We never see a mobile phone in the film, for example. Apart from the murder, it depicts a kind of utopian gay world – one that is hard to find today in the age of social media. I want to ask again about nostalgia, because Staying Vertical feels as if it’s looking at another lost culture. Marie, the shepherd and the mother of Léo’s child, resents having to work on her father’s farm. She’s not attached to the land in the same way as her father is. Upon leaving, we know it’s the end of a certain way of rural life.

Alain: Yes, it’s true, there’s also a lot of nostalgia in Staying Vertical. It’s a way of looking at the future with your own nostalgia. But I think what I’m showing are a lot of different ways of life that are in the process of disappearing in France. Even the practices of raising the livestock and the sheep are vanishing. In the future, will we see old guys like Marcel sitting idly by the side of a country road blasting music? When I was a kid, I used to see a lot of guys like him, but this is not the case any more. It’s a film that mixes very contemporary social and political issues we’re dealing with in the new ways we live today, and contrasting them with these vanishing modes of life.

Staying Vertical, 2016 Courtesy film still; Wild Bunch

Paul: The first film of yours I saw was No Rest for the Brave (2003). It begins with a lengthy conversation in a café between two friends. Igor is listening to Basile rave about a strange creature he met in a dream. Basile is convinced that if he falls asleep, he’ll die, and the rest of the movie is about him staying awake. I bring it up because dreams are such a central motif in your work. Your films operate on a kind of dream logic, oscillating between the real and the imagined without clear distinction between the two realms. The final scene of Staying Vertical is miraculous for this reason. We return to the plateau where Léo and Marie met, but now he is the shepherd. Léo is cradling a lamb in his arms while a pack of wolves circles him.

Alain: It was the hardest scene to direct in Staying Vertical. It was very hard. As a filmmaker, when you work with children and animals, you know that you have to accept what they give you. This is definitely true with wolves! And in this case, we had nine wolves on set, along with a trainer. In terms of filmmakers, I feel closer to David Lynch or Bunuel. I’m someone who has a very active dream life, and unlike many people, I tend to remember all of my dreams. For me, a good day begins when I sit and write down what I dreamed about that night. Although you can never really capture in writing what the dream was really like. I’m very interested in these parallels between dreams and filmmaking because I think that the process of creating a dream is very close to that of making a film. I can’t really say what role my own dreams play in the films I make because it’s not a direct one-to-one relationship, but I know they infuse the creative process in some way. I think my dream film would be to make the dream actually real in a movie, or at least to create a kind of hallucinatory reality. Perhaps the second option is the better one!